How the U.S. came to enter World War I

Part II.D(2) of my book; also known as "When the U.S. and Iran were besties--Long Version."

Overcoming U.S. neutrality

With much of the world already seemingly at war by the fall of 1914, a majority of the U.S. public considered itself lucky not to be entangled and strongly supported U.S. neutrality. President Woodrow Wilson, who had been elected in 1912 after Theodore Roosevelt turned on his former protégé Taft and ran as a third party candidate, was successfully re-elected in 2016 on the slogan “A vote for Wilson is a vote for peace.”[1]

Across the globe, the ancient nation of Persia (which would re-name itself Iran in 1935) shared the United States’ fervent desire to maintain neutrality between the European powers, and in fact had been enlisting the help of American diplomats and private financial experts since 1910 to help its government carve an independent path between the competing influences of Britain and Russia.

Neither nation, it turns out, would be able to defend themselves against the foreign covert intrigues on their soil, as the warring European powers, stalemated on the Western Front, were doing anything in their power to pull new allies and resources into the war’s destructive vortex. The populations of both Persia and the United States both became subject to a propaganda tug-of-war between the spy-versus-spy maneuverings of Germany and Great Britain. Germany found no shortage of people in either United States or Persia amenable to hearing its anti-colonial, anti-British message (despite the outright genocide that Germany had carried out between 1904 and 1908 against the Herero and Nama peoples in Germany’s West African colonies, now modern-day Namibia).

Nonetheless, by the end of 1917, the United States would be sending the flower of its youth to die in the trenches for Britain, France and Russia, while Persia would end up occupied by Turkish, Russian and British troops, its people starving to death as the Russians withdrew and the British increasingly solidified their control over the region.

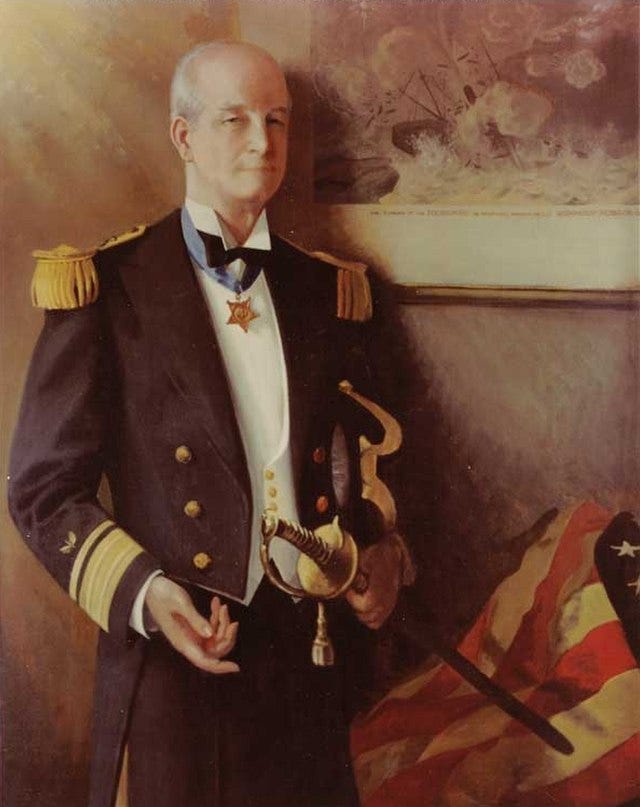

When war broke out between the European powers in 1914, the United States had its own priorities. Congressman Richmond P. Hobson, a naval war hero from the Spanish-American War, had returned to the United States from his later service in the Philippines impressed with the ability of a strong national government to combat the scourge of opium (apparently, he had not noticed the rise in organized crime that resulted). In December 1913, he enthusiastically greeted a march on Washington organized by the nation’s two most powerful temperance organizations, the Anti-Saloon League and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, and he proceeded to introduce a resolution in Congress for a constitutional amendment banning alcohol. He would later become known as the “father of Prohibition.”[2]

Certainly, neither Irish-Americans nor the eight million German-Americans (the latter constituting one tenth of the entire U.S. population) favored entering the war on the side of Great Britain. A contingent of politically active German-Americans, known in some circles of Congress as “the brewers,” were busy fighting with Congressman Hobson’s allies over the prohibition of alcohol.[3]

Jewish-Americans also generally favored the German cause and could not fathom the United States joining any alliance that included Russia, given the recent history of pogroms. As for African-Americans, noted scholar W.E.B. DuBois, writing for the Atlantic Monthly in May 1915, located the roots of European conflict in the late-19th century Scramble for Africa, observing that the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 had “turned the eyes of those who sought power and dominion away from Europe” and had led to the 1885 partition of Africa. He said, “We speak of the Balkans as the storm-centre of Europe and the cause of war, but this is mere habit. The Balkans are convenient for occasions, but the ownership of materials and men in the darker world is the real prize that is setting the nations of Europe at each other's throats to-day.” In order to bring about real peace, he argued, “[w]e must extend the democratic ideal to the yellow, brown, and black peoples.[4]

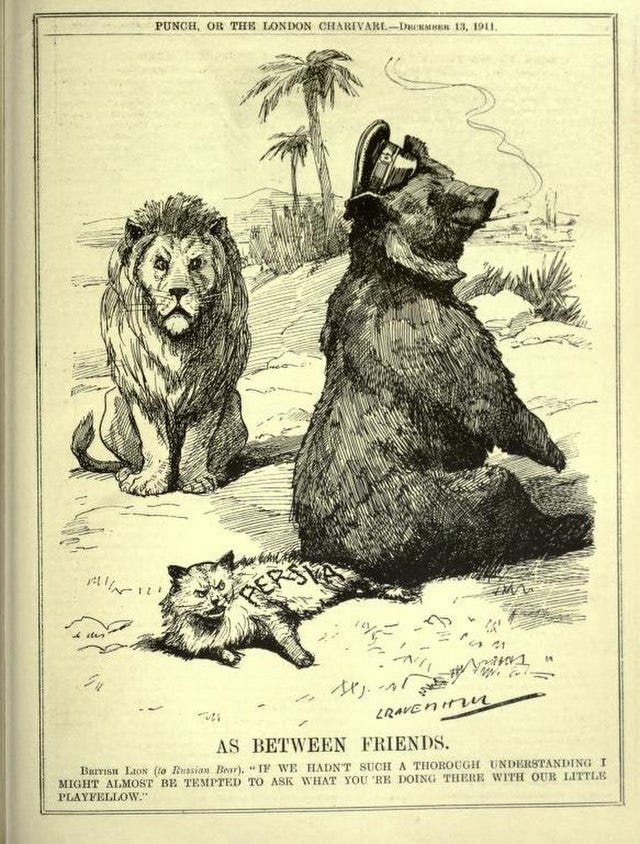

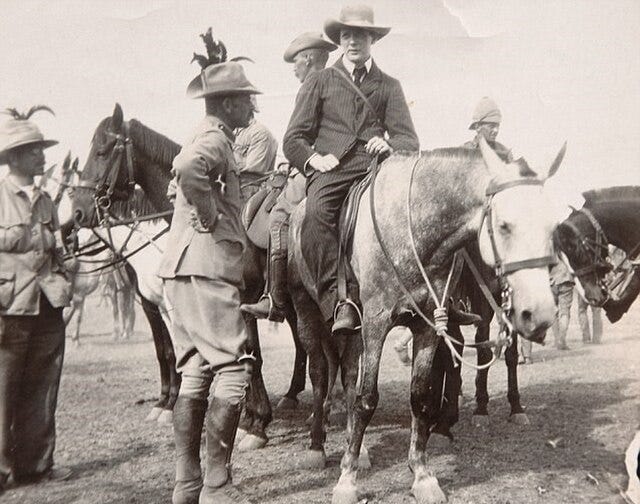

Across the globe, one of the world’s oldest civilizations and a nominally independent nation, Persia, was also trying its best to maintain its neutrality with the help of its American allies. Long squeezed between Russia and Britain, who had already secretly agreed in 1907 to divide up the territory of this independent country between themselves—despite their professed devotion to territorial integrity under the Westphalian nation-state system that purportedly underpins modern international relations—Persia in 1910 had asked the U.S. State Department for assistance in obtaining finance administrators “who were free from any European influence” to help sort out its archaic system of finances. Persia was at that time heavily in debt to Russia and Britain and trying to build railroads and other infrastructure. American W. Morgan Shuster was eventually selected to enter into a three-year contract to serve as Treasurer-General to the Persian Empire. Shuster assembled a team of American financial advisors, most of whom had gained valuable experience as customs or tax officials in the Philippines, and took up residence in Teheran in 1911, enthusiastically welcomed by the cultured local elites.[5]

There had been some turbulence in recent Persian history, with tensions between a succession of Shahs and those advocating for a constitutional monarchy. By 1913, however, Persia was trending strongly towards democratic governance with a freely elected Majlis (Parliament). The U.S. Minister in Tehran, Charles Welles Russell, was reporting back to the U.S. State Department that “I have just heard an outside adviser, who has been in Persia for nearly two years, say that Persia is now in better condition that at any time since he came.”[6] Russell was beloved by his Persian hosts; his daughter played tennis with the young Shah.[7]

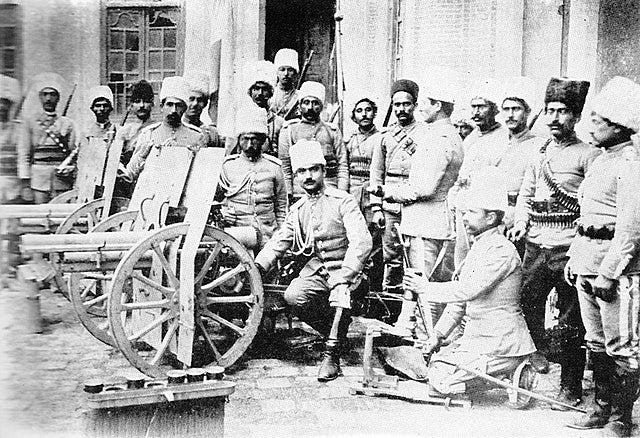

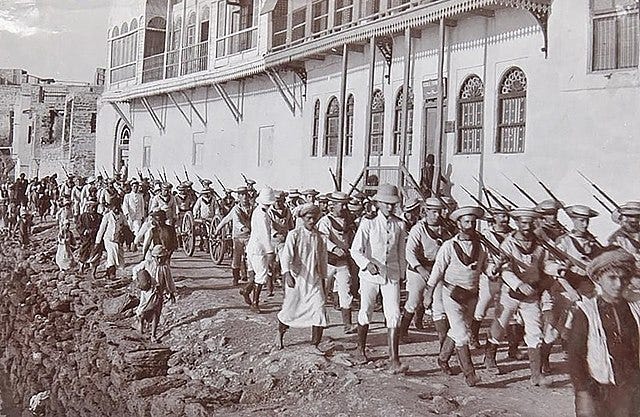

But the American interest in Persia had come far too late to do much about the apparent British and Russian hostility to democratic and representative government in Persia. The Russians quickly engineered the dismissal of Shuster from Persia,[8] and the British government acquired a 2/3 interest in the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, which held the oil concession for Persia.[9] The British were already sending troops from Central India directly onto southern Persian territory as early as 1911, citing brigandage and general lawlessness as justification. The Persians responded by forming their own gendarmerie under the leadership and advice of Swedish military officers, but the British strongly preferred that such a force be headed by British officers.[10] In October 1913, Russell reported on the establishment of an independent gendarmerie under an American military officer, Colonel J.N. Merrill, formerly of the Philippine Constabulary, who signed a three-year contract with the Persians to organize and command a unit in Fars.[11]

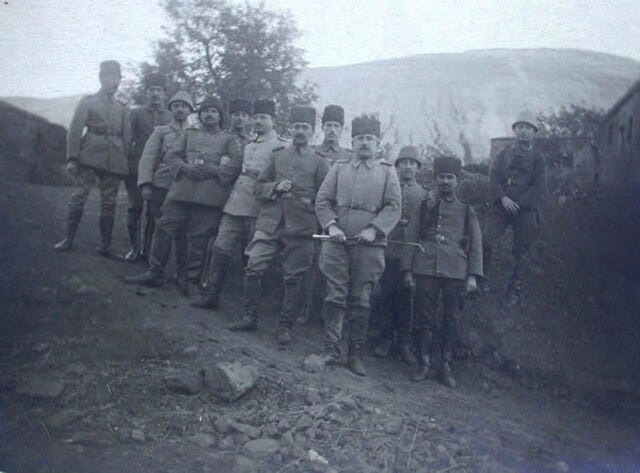

With the outbreak of World War I, Russia quickly moved to settle its remaining differences with Britain in order to pursue purportedly “centuries-old desires” of the Russian Empire to acquire much of northern Persia: the city of Constantinople, the western shore of Bosporus, the Sea of Marmora and the Dardanelles and everything south to the Enos-Media line.”[12] Persians resented these “centuries-old desires” and tended on the whole to be sympathetic to the Ottoman Empire; when the Chief Mullah of Turkey issued a fatwa declaring holy war (jihad) in December 1914, the Shia Mujtahids in Kerbala and Najaf issued a fatwa directing the Persian government to side with their fellow Muslims.[13]

The outbreak of hostilities also prompted a flood of German covert agents into the region, supporting Persian longtime popular resistance against Russian and British semi-colonial dependence, and hoping to stir up trouble in British India as well.[14] The Germans were eager to win over the Iranian gendarmerie that was under Swedish leadership.[15] A particularly effective German agent, a businessman named Pugin, dressed as a Persian and convinced many of the citizens of Isfahan that the Germans had all been converted to Islam and that the German Kaiser was a “Haji.”[16] In March 1915, British Sepoy troops surrounded the German consulate at Bushehr, on Persian soil, and “arrested” the German consul, Dr. Listemann and his wife, alleging “political activities.”[17]

The “arrests” enraged Persian government officials, particularly the pro-democracy and pro-German elements of the Majlis, as reported by Russell’s successor at the American legation in Tehran, John Lawrence Caldwell. By April 1915, as Caldwell reported to Washington, the Russians and British were demanding the resignation of Prime Minister Moshir-ed-Dowleh, the dissolution of the freely elected Majlis, and the installment of a Russian protected subject as the new prime minister. While the Russians’ choice was not ultimately approved as prime minister, Moshir-ed-Dowleh was compelled to resign. A Russian force landed at Enzeli, a port on the Caspian Sea, and proceeded to occupy all of Azerbaijan.[18]

Persians continued to appeal to Caldwell for American assistance in countering these infringements upon their national sovereignty, as American missionaries were also reporting to him the massacres at the hands of Russian forces moving through northern Persia. When rumors began circulating about the possibility of Russian troops marching into Tehran, the Germans leased property adjoining the American Legation, according to Caldwell, in order to be able to quickly seek diplomatic protection there.[19] The German ambassador to the United States in Washington also complained directly to the U.S. Secretary of State about the arrest of two Germans in Shiraz by the British.[20]

Woodrow Wilson, along with many members of the American public, may not have been engaged by all the activity in Persia, but he certainly was concerned about the foreign intelligence intrigues occurring on U.S. soil. While the Germans were conspiring with the Sikhs and Irish-Americans, the British were equally determined to foment anti-German sentiment among U.S. immigrants from Czechoslovakia, the Balkans and Poland.[21] Today, such activities might have been tracked by the Foreign Malign Influence Center (FMIC) under the U.S. Director of National Intelligence (DNI)—of course, with a current emphasis on Iran and Russia as the leading foreign malign influences.[22]

But Wilson’s own Cabinet was internally divided with regard to Wilson’s neutrality policy and did not enforce it uniformly.[23] Wilson’s Anglophilic new Secretary of State, Robert Lansing, who replaced William Jennings Bryan in the role in June 2015, soon found cause to upbraid Caldwell in Tehran, who was reporting on the recent atrocities committed by a Russian-sponsored “Christian militia” from Syria against local Muslims.[24] On November 17, 1915, Lansing wrote to Caldwell, “Various reports which have reached the Department, to which your own despatches to Department lend color, seem to indicate that you are not preserving the attitude of strict neutrality and absolute impartiality required of diplomatic representatives of the United States…You are instructed to refrain from any action which might give the impression that you are in sympathy with one of the belligerents.” British officials apparently were conveying to Lansing separately through the U.S. embassy in London their “surprise at the action of the American minister in Tehran for taking charge of German, Austrian and Turkish interests in Persia.”[25]

As for the foreign subversion on U.S. soil, Wilson’s Attorney General, Thomas Watt Gregory, told Wilson that the foreign covert agents were not violating any federal law and refused to investigate matters that were not a violation of federal law. The Bureau of Investigation (BI), created in 1908 under the Attorney General’s administrative authority, by 1915 still consisted of only a “small and inept force of 219 agents” that had no intelligence mission.[26] Congress had passed a bill in 1911 during a Japanese war scare “to prevent the disclosure of national defense secrets,” but that law did not apply to this particular variant of espionage. There were two criminal laws regarding U.S. neutrality, one that prohibited the enlisting of men to fight in a foreign army against a nation with which the United States was at peace, the other prohibiting organizing a military expedition against a nation with which the United States was at peace. Neither of these applied, either. [27]

In the meantime, there was a great deal of money to be made supplying arms, munitions, horses and other war materiel to the Entente (also known as the Triple Alliance). Between August 1914 and April 1915, French purchases in the United States per month rapidly increased from 53.8 million francs to 186 million francs. The British, working through the New York-based J.P. Morgan and Company as their sole agent for arms purchases, spent 237.8 million pounds in 1915, an increase of 75 percent in spending from 1913.[28] Germany also tried to obtain American goods using German treasury bills, but the few U.S. banks willing to trade with Germany quickly capitulated to British threats of blacklisting.[29] The British naval blockade, supported by its intelligence services, usually prevented even the few successful German arms purchases from reaching their destination.[30]

German officials in the United States thus were mostly relegated to sabotaging U.S. shipments to the Triple Alliance. They started with Unterseeboot or “U-boat” attacks on merchant vessels crossing the Atlantic. Initially, a few ships were sunk with no loss of life, as the crew was typically allowed to escape by lifeboat first. That changed with the May 17, 1915, sinking of the British passenger cruiser Lusitania, which was en route from New York to Liverpool, carrying over a thousand passengers and, allegedly (as believed by Germany and furiously denied by Britain), a shipment of high explosives, when it was destroyed off the coast of Ireland.[31] Nearly 2,000 civilian passengers lost their lives, including 124 Americans. The U.S. press denounced the German “Huns” as “barbaric” and “villainous.”[32]

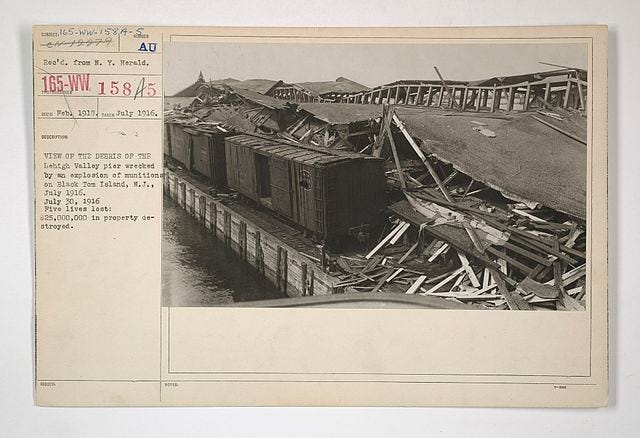

On July 30, 1916, residents of New York and New Jersey were awakened in the pre-dawn hours by a tremendous explosion that shattered windows in mid-town Manhattan; German saboteurs had detonated an enormous ammunitions depot on “Black Tom” island near the Jersey City harbor.[33] In Newport News, Virginia, thousands of horses awaiting transport to Europe were poisoned with anthrax developed by German-American surgeon Anton Dilger.[34] Irish stevedores working in U.S. shipyards were often more than happy to assist the Germans.[35]

Such efforts were being coordinated globally through the section of the German Army’s General Staff called the IIIrd Oberquartiermeister, or “IIIb,” that largely served as its intelligence bureau, and that was led by Prussian Major Walther Nicolai. The most famous of the IIIb’s agents during World War I was Mata Hari, who was eventually unmasked and shot by the French in early 1917.[36] But the Germans’ sabotage and other HUMINT efforts in the United States never amounted to much, largely due to the superior British intelligence apparatus, which was already active enough in the United States to more than make up for the U.S. Government’s own serious deficiencies in the area of counter-espionage. The British had learned valuable lessons about the importance of military intelligence while fighting the Boer War in South Africa in 1899—the use of spies against Boer guerrillas had made a particularly strong impression on 25-year-old war correspondent Winston Churchill[37]—and well prior to the outbreak of World War I, they had created both a Security Service under the Home Office, which was focused on internal security and was later to be designated MI5; and a Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) under the Foreign Office, which was later to be designated MI6. Both of them were initially predominantly focused on German espionage.[38]

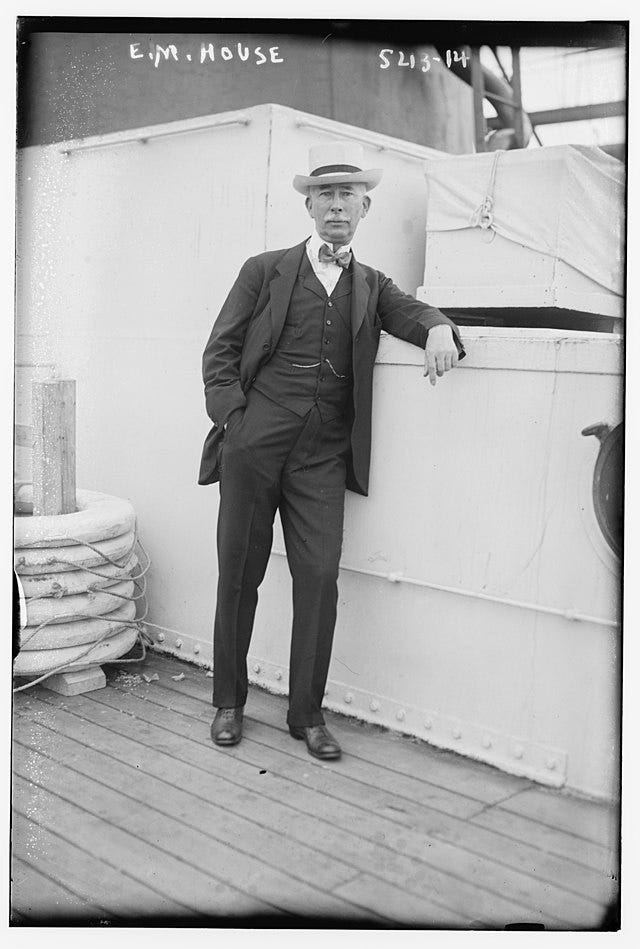

In addition, the British had military and naval intelligence. In January 1914 Australian-born Captain Guy Gaunt was assigned to serve as naval attaché out of the British consulate in New York. The extroverted Gaunt’s social circle quickly came to include Teddy Roosevelt, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin Delano Roosevelt, J.P. Morgan partner Edward Stettinius, and President Wilson’s closest advisor, “Colonel” Edward M. House. House sang Gaunt’s praises in a letter to First Lord of the Admiralty Arthur J. Balfour, noting that “I have been able to go to him at all times to discuss, very much as I would with you, the problems that have arisen.”[39]

What Colonel House didn’t fully appreciate was that the British, while starting to cultivate a “special relationship” with their newest co-imperialist, were at the same time carrying out a covert propaganda operation, mirroring all their maneuverings against Germany in Persia, in order to blunt the U.S. public’s support for neutrality and pull the United States into the conflict. For the British covert agents operating in the United States, the German sabotage efforts were not so much a serious security threat as a basis for propaganda. British publishers began publishing American authors with book titles like German Conspiracies in America and America and the German peril.[40]

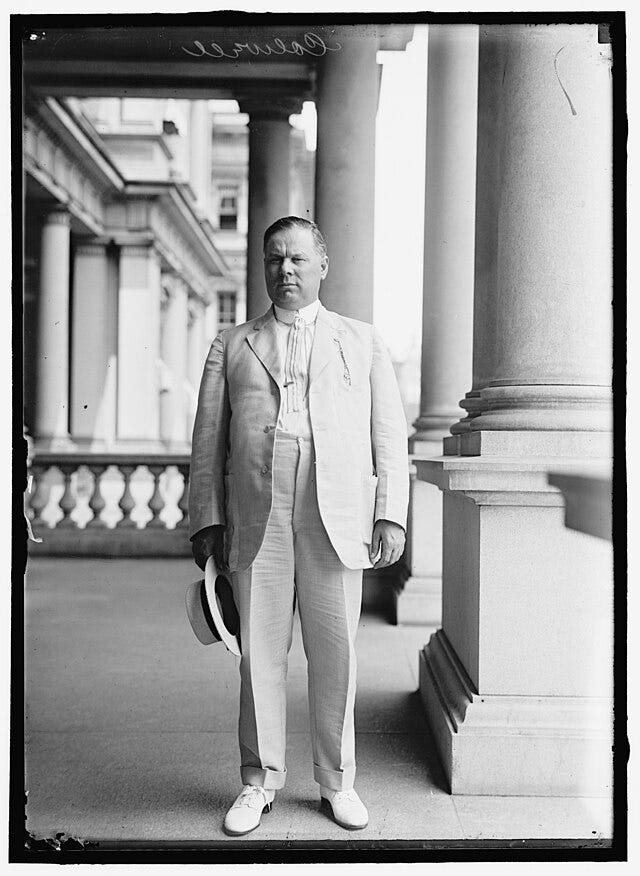

The federal executive branch under President Wilson was not just guileless and internally divided between pro-neutrality and pro-British sympathies, it was also bureaucratically incompetent, with BI agents under the Justice Department and U.S. Secret Service agents under the Treasury Department constantly “battling amongst themselves” in an effort to find evidence against the Germans. As for SIGINT, in 1913, a bored, 23-year-old code clerk at the U.S. State Department named Herbert O. Yardley had discovered one night to his astonishment that he could easily decrypt in a matter of hours a 500-word message from House to Wilson, sent using U.S. diplomatic codes; Yardley’s warnings to his superiors that the codes were vulnerable went unheeded.[41] Indeed, in London, the SIS was routinely reading the U.S. ambassador’s telegrams to and from the State Department.[42] The U.S. War Department’s code, meanwhile, was stolen by Germans from U.S. forces in Mexico during a punitive expedition undertaken by the latter in 1916.[43]

British SIGINT frequently revealed German sabotage plans, and rather than foil the plots themselves, the British passed on information to trusted contacts, usually either in the U.S. Secret Service or the New York Police Department (NYPD)’s bomb squad and let them make the arrests. Once those arrests occurred, the British would then amplify and publicize them in the U.S. press.[44] Wilson observed to House in August 1915, “I am sure that the country is honeycombed with German intrigue and infested with German spies. The evidences of these things are multiplying every day.”[45] A month later, an assistant attorney general in the U.S. Justice Department wrote the first draft of the Espionage Act, concluding, as had Wilson, that federal laws were wholly inadequate to protect against “our comrades and neighbors” who “have sought to pry into every confidential transaction of the government in order to serve interests alien to our own.”[46]

Congress, however, refused to act. Opponents of the legislation included Illinois Representative Frank Buchanan, organizer of a committee to oppose munitions manufacturing, had been indicted on federal charges of conspiracy in restraint of trade. He believed the BI, in investigating him, was simply “interfering with labor under the guise of maintaining neutrality.”[47]

In late 2016, the SIS sent Sir William Wiseman to Washington, who promptly convinced Colonel House that he, rather than the U.K. Ambassador, could provide a direct channel of communications with the new Prime Minister, David Lloyd George.[48] This came at a moment when Wilson and House were engaging in a bit of personal diplomacy with the German government, which was purportedly seeking a peaceful settlement to the entire conflict, and were attempting to bypass their own Secretary of State, Lansing,[49] whom they seemed to realize was now firmly in the British camp.

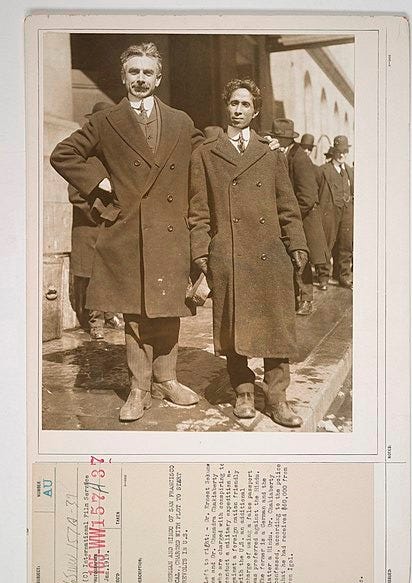

British agents were also working with the NYPD to unmask the inner workings of the Berlin India Committee. Between April 1916 and January 1917, a series of telegrams between German Foreign Secretary Alfred Zimmerman and the German ambassador to the U.S., which most likely had been intercepted by the British and then decrypted by the British navy’s cryptographic unit known as “Room 40,”[50] provided evidence of the German Foreign Office’s support of the Indian revolutionaries. On March 6, 1917, the NYPD arrested Berlin India committee representative Chandra Kanta Chakravarty and his “traveling companion,” the German agent Ernest Sekunna, and several other German consulate officials. In San Francisco, U.S. Attorney John Preston met with British agents to discuss the possibility of charging a number of individuals with violating the U.S. neutrality law, by organizing military expeditions against a country with which the United States was at peace. [51]

But the real coup for the British influence campaign arrived when Zimmerman sent a January 17, 1917 cable to his minister in Mexico that read in large part as follows:

We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis:

Make war together, make peace together, generous financial support, and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona…

[The President of Mexico] should, on his own initiative, invite Japan to immediate adherence and at the same time mediate between Japan and ourselves.[52]

Room 40 readily decrypted this telegram, in large part because a duplicate of it had been sent through American diplomatic channels, which the British were routinely intercepting.[53] The decrypt was quickly passed to Arthur Balfour, who had gained an appreciation for SIGINT while serving as First Lord of the Admiralty but was now the Foreign Secretary. Balfour immediately recognized its propaganda value and permitted the cable to be passed to the U.S. government, bypassing Prime Minister Lloyd George.[54] President Wilson read the telegram on February 25, 1917, and was “as shocked and angry” as British intelligence had hoped he would be. Wilson decided that the telegram should be published immediately, and the top headlines in the New York Times on March 1 read, “Germany Seeks an Alliance Against US; Asks Japan and Mexico to Join Her; Full Text of her Proposal Made Public.”[55]

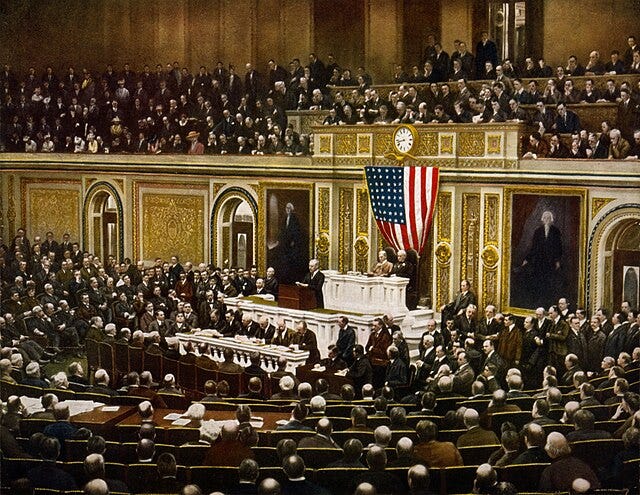

While Wilson had already broken off diplomatic relations with Germany in February following Germany’s resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare, the notion that Germany would offer back to Mexico the territories the U.S. had conquered in the Mexican-American War was a bridge too far for large swaths of the American public. In Washington, Wiseman sat with House and jointly prepared a memorandum on American attitudes towards Britain and the war, which Wilson approved for transmission to London in time for an Imperial War Conference to be held in London at the end of March.[56] On April 6, 1917, Wilson addressed a joint session of Congress, calling for a formal declaration of war on Germany, noting that the Zimmermann telegram provided “eloquent evidence” that the “Prussian autocracy was not and could never be our friend…its spies were here before the war began” and “means to stir up enemies at our very doors.” The “spectacular public impact” of the Zimmerman telegram earned the Director of Naval Intelligence, Admiral William Reginald “Blinker” Hall, a knighthood.[57]

The addition of U.S. troops to the Western Front, once drafted, trained and shipped to Europe, was to prove to be the decisive factor leading to victory over the Central Powers. In Tehran, however, Caldwell was more focused on a no less important historic event that was of more immediate interest to nominally independent Persia than to the United States, but that would have profound long-term ramifications for both countries. On April 30, 1917, he reported “[s]ome agitation especially in Tabriz in northern Persia and in Teheran by some democrats and others encouraged by local Russian subjects for a republic. Disaffection reported among the Russian troops in Persia.”

As it became evident to him that the Tsarist government in Moscow had been overthrown, Caldwell observed to the U.S. ambassador in Moscow,

You see, all happenings in Russia are of peculiar and timely interest to us here in Persia and we hang breathless on every word uttered or hint dropped by our northern neighbor…Suffice it to say that the popular government party, including the Democrats and many others, has received great encouragement from recent happenings in Russia and the many utterances of Duma and Cabinet officers with reference to the Russian change of attitude towards Persia.[58]

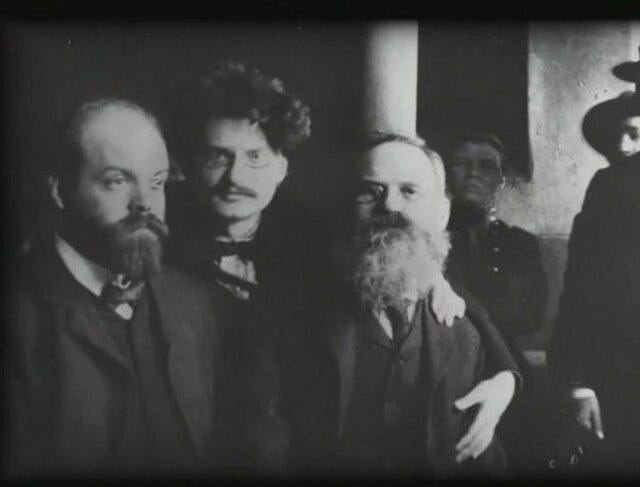

For a few months after Tsar Nicholas II’s abdication in March 1917, it was unclear what Russia’s policy would be towards Persia, or for that matter, whether Russia would become a Western-style democracy. But an exiled Russian named Israel Lazarevich Gelfland, who used the communist nom de guerre “Parvus,” had been “consulting” with the German Foreign Office in Berlin since 1915, in much the same spirit as had the Ghadar Party in San Francisco. Parvus successfully convinced the Germans that the interests of Germany and Russian revolutionaries were identical, and together they hatched a plan to bring about Bolshevik rule in Russia in order to pull Russia out of the Triple Alliance entirely.[59]

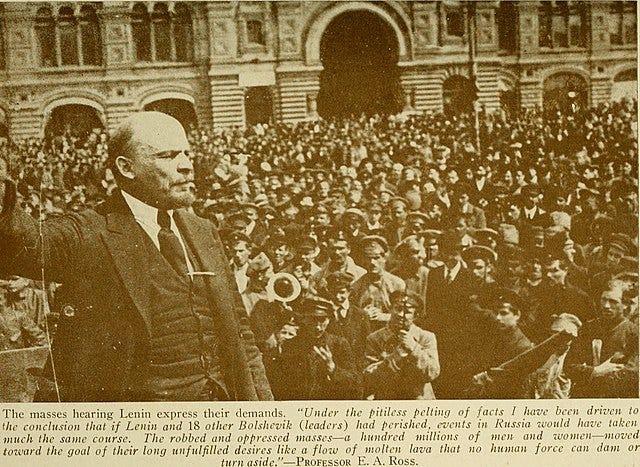

On April 16, 1917, a train arrived in St. Petersburg carrying 32 additional Russian exiles, at least one of whom had somehow made it through hostile German territory all the way from Zurich, Switzerland. This single individual, Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov, would proceed to speak and write at a frenetic pace to delirious crowds, spreading the Bolshevik message; as Winston Churchill would later describe his arrival, it was as if a “plague bacillus” had been injected into the Russian body politic at the precise moment where it could do the most harm.[60] Ulyanov would only live until 1924, but five days after his death, St. Petersburg would be re-named after his nom de guerre: Lenin.

[1] A. Scott Berg, Wilson 416 (2013).

[2] Lisa McGirr, The War on Alcohol: Prohibition and the Rise of the American State (W.W. Norton & Company: New York and London, 2016), at 3-5.

[3] Ironically, the fight in Congress between ex-Congressman A. Mitchell Palmer, then pursuing the position of Attorney General, and U.S. Senator Boies Penrose of Pennsylvania, would later inadvertently reveal to the public the fact that the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Investigation (BI) had created an index of “pro-German” political figures during World War I, who also supported “the brewers.” Specifically, towards the end of World War I, Palmer accused the Senator of receiving political support from “the brewers” and added that “the brewers” were also pro-German and thus unpatriotic. A Congressional investigative committee dealing with pro-Germanism asked for more information from Bruce Bielaski, then the head of the BI, and learned that the BI had an index of “pro-German” sympathizers that included, inter alia, William Jennings Bryan, Woodrow Wilson’s first Secretary of State. Max Lowenthal, The Federal Bureau of Investigation (New York: William Sloane Associates, 1950), pp. 22-23, quoted in Dr. Harold C. Relyea, Congressional Research Service, “The Evolution and Organization of the Federal Intelligence Function: A Brief Overview (1776-1975), contained in Book VI of the Final Report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities,” United States Senate (U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, 1976), at 96-97.

[4] W.E.B. DuBois, “The African Roots of War,” Atlantic Monthly, May 1915, at 707, available online at http://www.webdubois.org/dbAfricanRWar.html (last viewed December 1, 2024).

[5] W. Morgan Shuster, The Strangling of Persia (The Century Co.: New York, 1912), at 3-4. The background and qualifications of Shuster’s team is discussed in the footnotes at 6-8.

[6] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 12.

[7] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 15.

[8] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 143.

[9] Mohammad Gholi Majd, The Great Famine and Genocide in Persia, 1917-1919 (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 9.

[10] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 22.

[11] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 25.

[12] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 53.

[13] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 33.

[14] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 45-46. In the spring of 1915, the tempo of German subversion in the region increased sharply upon the return of the German envoy Prince Reiss to Tehran following a long absence. Id. at 55.

[15] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 60.

[16] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 61-62.

[17] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 41.

[18] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 58.

[19] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 60.

[20] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 41-42.

[21] Joan M. Jensen, the Price of Vigilance (Rand McNally and Company: Chicago, New York, San Francisco, 1968), at 10.

[22] The FMIC was authorized under 50 U.S.C. §§ 3058, 3059 and began operations on September 23, 2022. Foreign Malign Influence is defined as “defined as subversive, undeclared, coercive, or criminal activities by foreign governments, non-state actors, or their proxies to affect another nation’s popular or political attitudes, perceptions, or behaviors to advance their interests.” See https://www.dni.gov/index.php/nctc-who-we-are/organization/340-about/organization/foreign-malign-influence-center (last viewed December 1, 2024).

[23] Specifically, Wilson’s Secretary of State from 1913 to 1915, was wary of Wilson’s “stern policy” towards Germany, to the point that, in 1915, he resigned and was replaced by Anglophile Robert Lansing. Bryan did want to pursue German espionage efforts, however, and because Gregory did not want to assign BI agents to the task, Treasury Secretary William McAdoo, who hoped to replace Bryan when he resigned, enthusiastically assigned Secret Service agents instead, who liaised with the New York Police Department (NYPD). Joan M. Jensen, the Price of Vigilance (Rand McNally and Company: Chicago, New York, San Francisco, 1968), at 13.

[24] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 37.

[25] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 47.

[26] Dr. Harold C. Relyea, Congressional Research Service, “The Evolution and Organization of the Federal Intelligence Function: A Brief Overview (1776-1975), contained in Book VI of the Final Report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities,” United States Senate (U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, 1976), at 95.

[27] Joan M. Jensen, the Price of Vigilance (Rand McNally and Company: Chicago, New York, San Francisco, 1968), at 10-12.

[28] Hew Strachan, The First World War, Vol. I: To Arms (Oxford University Press, 2001), 963.

[29] Hew Strachan, The First World War, Vol. I: To Arms (Oxford University Press, 2001), 944.

[30] For example, Franz von Papen, the military attaché for the German Ambassador to the United States, purchased 7,300 rifles, 1,920 revolvers, ten Gatling guns, and 3 million rounds, arranging for their transportation from New York on a ship belonging to the Holland-America Line. British intelligence traced the cargo, tipped off Holland-America, and the company refused to transport the goods. Hew Strachan, The First World War, Vol. I: To Arms (Oxford University Press, 2001), 800.

[31] John Bell, “Logistics and American entry into the Great War,” April 1, 2017, Defense Logistics Agency, available at https://www.dla.mil/About-DLA/News/News-Article-View/Article/1162583/logistics-and-american-entry-into-the-great-war/.

[32] Howard Blum, Dark Invasion 1915: Germany’s Secret War and the Hunt for the First Terrorist Cell in America (Harper Perennial, 2014), at 337-38.

[33] Howard Blum, Dark Invasion 1915: Germany’s Secret War and the Hunt for the First Terrorist Cell in America (Harper Perennial, 2014), at 412.

[34] David Pfeiffer, “’Tony’s Lab’: Germ Warfare in WWI Used on Horses in the U.S.,” Prologue Magazine, Fall 2017, Vol. 49, No. 3, available through U.S. National Archives website at https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2017/fall/tonys-lab (last viewed December 1, 2024).

[35] See “In the Crosshairs: Allied Shipping,” Intelligence.gov (a publication of the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence), available at https://www.intelligence.gov/evolution-of-espionage/world-war-1/undeclared-war/allied-shipping (last viewed December 2, 2024).

[36] David Kahn, Hitler’s Spies: German Military Intelligence in World War II (MacMillan Publishing Co., New York, 1978), at 32, 35-36.

[37] Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2018), at 450-51.

[38] Keith Jeffery, MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909-1949 (Bloomsbury Publishing: London, 2010), at 13-14; Christopher Andrew, Defend the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 2009), at 3-52.

[39] Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2018), at 522-23.

[40] Jennifer Luff, “The Anxiety of Influence: Foreign Intervention, U.S. Politics, and World War I,” Diplomatic History 44(5): 756-785 (November 2020), at 763-64.

[41] David Kahn, The Code Breakers (The MacMillan Company, 1972), at 351; Herbert O. Yardley, The American Black Chamber (The Bobbs-Merrill Company: Indianapolis, 1931), at 17-31.

[42] Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2018), at 516.

[43] Herbert O. Yardley, The American Black Chamber (The Bobbs-Merrill Company: Indianapolis, 1931), at 40.

[44] Jennifer Luff, “The Anxiety of Influence: Foreign Intervention, U.S. Politics, and World War I,” Diplomatic History 44(5): 756-785 (November 2020), at 769-70.

[45] Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2018), at 522.

[46] Jennifer Luff, “The Anxiety of Influence: Foreign Intervention, U.S. Politics, and World War I,” Diplomatic History 44(5): 756-785 (November 2020), at 774; the quote is from a speech Wilson gave in December 1915.

[47] Joan M. Jensen, the Price of Vigilance (Rand McNally and Company: Chicago, New York, San Francisco, 1968), at 10-12.

[48] Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2018), at 534.

[49] Ronald J. Granieri, “Woodrow Wilson’s Diplomacy, the First World War and the Quest for Post-War Peace,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, May 12, 2016, available at https://www.fpri.org/article/2016/05/woodrow-wilsons-diplomacy-first-world-war-quest-post-war-peace/ (last viewed December 2, 2024).

[50] The reason the British were able to intercept so many communications between Germany and the United States, which were then decrypted by “Room 40,” was that, on August 5, 1914, at the very outbreak of hostilities, the British had sent out a small cable ship before dawn to quietly cut Germany’s transatlantic telegraph cables just off the Dutch coast. David Kahn, The Code Breakers (The MacMillan Company, 1972), at 266. This left the Germans reliant on neutral Sweden to route its cable traffic, and Swedish cable traffic still passed through England. Sweden’s assistance to Germany violated neutrality laws, but British Naval Intelligence decided that “it was more advantageous to listen to what the Germans were saying than to stop them from talking.” Id. at 286. “Room 40” acquired its name when a small and novice cryptographic unit started by Director of Naval Education Sir Alfred Ewing at the outbreak of hostilities in 1914 had grown to the point that the unit no longer fit in Ewing’s personal office and were moved to Room 40 in the Old Building of the Admiralty. Later in the war the cryptographic unit was designated as Section 25 of the Intelligence Division, but the name “Room 40” stuck. Id. at 269. Ewing was replaced in October 2016 by Captain William Reginald “Blinker” Hall, who had a nervous tic that caused one of his eyes to twitch incessantly. Id. at 276.

[51] Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance & Indian Anticolonialism in North America (Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2014), at 58.

[52] Quoted in David Kahn, The Code Breakers (The MacMillan Company, 1972), at 292.

[53] During the German “peace initiative” of late 2016, the German Ambassador to the U.S. suggested that the chances of peace would be much improved if his government could communicate directly with President Wilson. The next day Wilson permitted the German government to send messages in its own code between Washington and Berlin under American diplomatic auspices. It was because of this arrangement that the Zimmerman telegram was encoded with German code, delivered to the U.S. Embassy in Berlin on January 16, routed through Copenhagen and then London, and then on to Washington. When the British cryptologists intercepted it, they were “highly entertained” at the sight of German code in an American cable. They already had a copy of the telegram that the Germans had sent to neutral Sweden for routing to Buenos Aires, which also touched on England. Having two copies of the same encrypted cable helped the codebreakers eliminate garbles. David Kahn, The Code Breakers (The MacMillan Company, 1972), at 284-85.

[54] Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2018), at 539.

[55] Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2018), at 540. To the delight of British officials, most of the U.S. press gave credit for obtaining the telegram to U.S. secret agents rather than the British, so the fact that Room 40 existed and was intercepting U.S. diplomatic communications was never revealed. Id. at 541-42.

[56] Keith Jeffery, MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909-1949 (Bloomsbury Publishing: London, 2010), at 115-16.

[57] Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2018), at 543.

[58] Mohammad Gholi Majd, Persia in World War I and its Conquest by Great Britain (University Press of America: Lanham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Oxford, 2003), at 142-43.

[59] Volker Wagener, “Germany’s Role in the Russian Revolution,” Deutsche Welle, Nov. 7, 2017, available at https://www.dw.com/en/how-germany-got-the-russian-revolution-off-the-ground/a-41195312 (last viewed December 21, 2022).

[60] Ted Widmer, “Lenin and the Russian Spark,” The New Yorker, April 20, 2017, available at https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/lenin-and-the-russian-spark (last viewed December 21, 2024).