C. Policing America’s Empire in the Philippines

Faced with the problem of subjugating 10 million people who did not wish to be subjects of the United States, U.S military forces in the Philippines first responded with racially-tinged brutality. When that became politically untenable for the Roosevelt Administration, they turned to more subtle means of control, utilizing similar methods of collecting and indexing data on individuals to those that Herman Hollerith had sold to the U.S. Census in 1890. In this manner, the United States developed the first building blocks of a uniquely American surveillance state, engaging in a form of political policing and censorship, including the imprisonment of newspaper publishers, that would have raised First Amendment concerns in the United States but was exempted from such scrutiny in the Philippines thanks to the Insular Cases. Starting in 1901, the U.S. Supreme Court articulated a very different theory of U.S. Government power than it had in Dredd Scott, this time deciding that not every provision of the U.S. Constitution applies where U.S. sovereignty exists, with specific regard to its new insular possessions. Which rights applied and where subsequently became a piecemeal, case-by-case determination, with the Philippines now primed to become a living laboratory for U.S. authorities to see how far they could push the limits of the U.S. Bill of Rights. At home, the U.S. Supreme Court opined that aliens could be denied entry to the United States and could be expelled purely on the basis of belief (anarchism), as aliens also were not among the “people” of the United States to whom certain Constitutional protections might otherwise apply.

Because U.S. authorities in the Philippines could engage in political policing, they could also traffic in political scandal, promoting the political fortunes of their generally more fair-skinned Filipino elite allies, while destroying the reputations of those who questioned the overall legitimacy of U.S. rule. Scandal-trafficking was further enhanced by what became some of the United States’ earliest experiments in federal vice regulation (opium, prostitution, gambling). Some forms of federal vice regulation then began to migrate home to the continental United States during what is known as the “Progressive Era.” One case, involving a federal prosecution for running a lottery, resulted in a Supreme Court decision on the 4th Amendment that for the first time articulated what is now known as the Exclusionary Rule.

(Honey, is this enough explanation?)

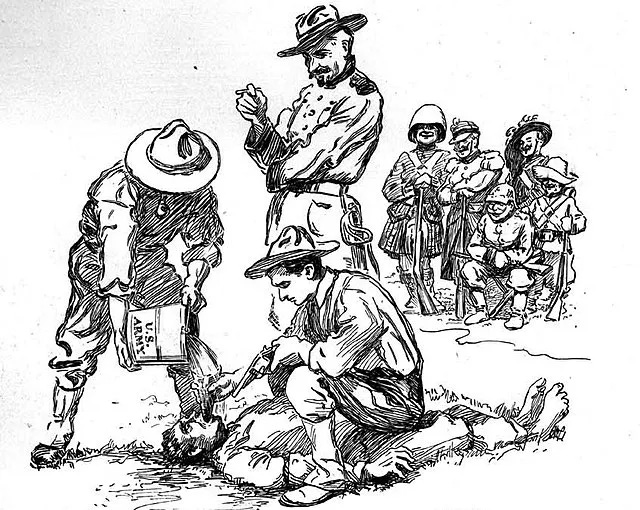

The readers of the Omaha, Nebraska World-Herald in May 1900 may have been the first in the United States to hear about a counterinsurgency interrogation technique being used by U.S. soldiers in the Philippines and referred to as the “water cure,” courtesy of a letter sent home by a member of the 32nd Volunteer Infantry Regiment (unlike cables, letters from soldiers were not subject to any sort of War Department censorship).[1] The technique had been used during the Spanish Inquisition and then brought to the Philippines during Spanish colonial rule, although it certainly was not limited to the Spanish, as the Dutch had also used it in present-day Indonesia in 1623.[2] In 1900, the technique involved simply forcing the victim to consume water; as the soldier from the 32nd Volunteer Infantry Regiment explained it,

“Lay them on their backs, a man standing on each hand and each foot, then put a round stick in the mouth and pour a pail of water in the mouth and nose, and if they don’t give up pour in another pail. They swell up like toads. I’ll tell you it is a terrible torture.”[3]

In the more modern iteration, the victim experiences the sensation of drowning but without actually being forced to consume and then regurgitate water; this technique is known as “waterboarding.”

By 1902, stories about the water cure and other atrocities committed by the U.S. Army in the Philippines as it waged its first-ever counterinsurgency campaign were causing considerable political uproar in the United States. The campaign was, in fact, the last foreign conflict the United States would ever fight without anti-war protests meeting severe domestic repression. Anarchist Emma Goldman and socialist activist Eugene Debs spoke out against it openly; twenty years later, they would both be arrested, jailed, and in Goldman’s case, deported, for saying virtually the same things with regard to World War I.[4] The wealthy owner of a small Philadelphia newspaper, who said that he “professes to believe in the gospel of Christ,” began to doggedly pursue any and all allegations regarding “the cruelties and barbarities which have been perpetrated under our flag in the Philippines.”[5] The issue was the subject of months’ worth of Senate hearings organized by Republican Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, at which the head of the new Philippine Commission, Ohio judge William Howard Taft, admitted to troops’ use of the “water cure” but then, in jocular fashion,

pointed to “some rather amusing instances” in which, he maintained, Filipinos had invited torture. Eager to share intelligence with the Americans, but needing a plausible cover, these Filipinos, in Taft’s recounting, had presented themselves and “said they would not say anything until they were tortured.” In many cases, it appeared, American forces had been only too happy to oblige them.[6]

The nascent Roosevelt administration’s Secretary of War, Elihu Root, quickly followed up with the Senate, submitting a much-less-jocular, 400-plus page tome entitled “Charges of Cruelty, Etc., to the Natives of the Philippines.” Most of Root’s report was devoted not to U.S. Army atrocities against Filipinos but about the Filipino insurgents carrying out “cruelties” against their countrymen, “conducted with the barbarous cruelty common among uncivilized races.”[7] But Lodge’s committee published a secret report written by the governor of Tayabas, Major Cornelius Gardener, who described brutalities committed mostly by U.S. soldiers and deep hatred developing between them and the locals as a result: “Almost without exception, soldiers, and also many officers, refer to the natives in their presence as ‘n—rs,’ and the natives are beginning to understand what ‘n—r’ means.”[8]

Something needed to change. The war in the Philippines had required 70,000 U.S. troops at its peak, and by 1902 had resulted in the deaths, either directly or indirectly, of about 600,000 persons, or one-sixth of the population of the island of Luzon. Many of these Filipinos had been corralled by the U.S. Army into concentration camps.

The ratio of dead to injured was was about fifteen to one, “almost a complete reversal of the typical dead-to-injured ratio in military combat.”[9] The war was also costing the United States millions of dollars a day.

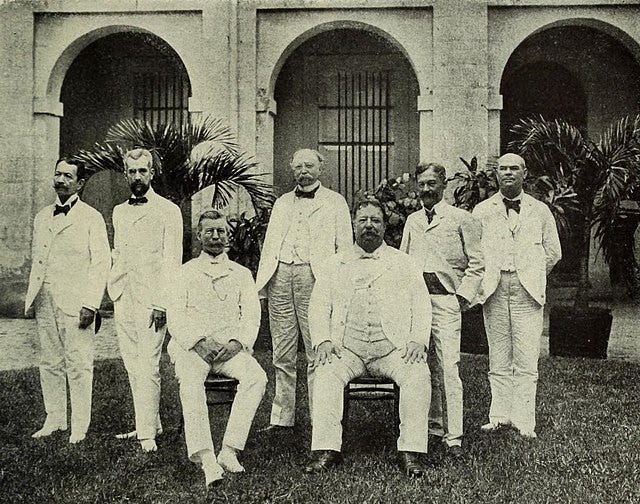

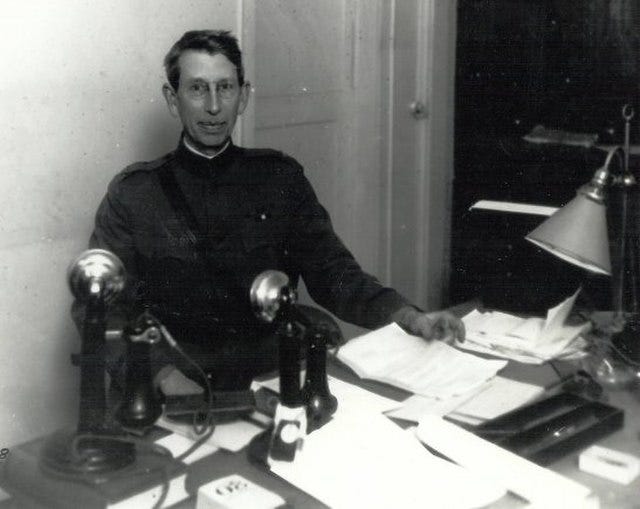

Enter U.S. Army Captain Ralph H. Van Deman, a Harvard-educated medical doctor-turned-infantry officer, today regarded as “the father of U.S. military intelligence.” Arriving at his post in Manila in February 1901, he was given command of the Division of Military Information (DMI). The DMI had been created by General Arthur MacArthur (whose son Douglas would one day famously return to the Philippines) in 1900 to help catalogue the masses of documents being captured from Filipino soldiers during the course of the counterinsurgency campaign.[10] Van Deman

quickly developed innovative doctrines for the DMI by collecting, categorizing, and operationalizing what soon became encyclopedic information on every aspect of the Filipino resistance: active guerrillas, civilian supporters, finances, firearms, ideology, propaganda, communications, movement, and terrain. Instead of passively filing documents and compiling monographs like the Military Information Division in Washington, Van Deman’s Manila command combined reports from the army’s 450 post information officers with data from the colony’s civil police to produce actionable field intelligence. With telegraph lines knitting nets around guerrilla zones and the captain pressing subordinates for fast, accurate information, DMI’s field units proved agile in tracking rebel movements and identifying their locations for timeline raids.

Exemplifying its voracious appetite for raw data, DMI launched a ‘confidential’ project in March 1901 to map the entire guerrilla infrastructure by compiling information cards for every influential Filipino…For rapid retrieval, DMI’s clerks transcribed these cards into indexed, alphabetical rosters for each military zone, including over two hundred initial entries for the Central Luzon region alone.[11]

The technique of profiling individual terrorists (or, sometimes, others) is today colloquially referred to in parts of the U.S. intelligence community as “baseball cards.”[12]

By July 1901 Aguinaldo’s army had been broken[13] and the U.S. transitioned to civilian rule.[14] At this point, Commissioner Taft established a police force called the Philippines Constabulary, with an Information Bureau staffed by a superintendent, three inspectors, two special detectives, a clerk, and a draftsman.[15] During its first year this bureau (later called the Information Section) compiled 2,034 identification photos and processed 7,620 reports from 22 undercover “operators.”[16] Its effective use of secret police, under the Constabulary’s first police chief, Henry Allen, presented a viable alternative to the “water cure” and other politically controversial coercive methods used by the U.S. Army. Allen, who had served in both the Military Information Division in Washington, DC and as a military attaché in tsarist Russia, seemed quite adept at creating a secret police. After just two months of police operations, he bragged to President Roosevelt that “had we known the people and the country upon arrival as we now do, the insurrection could have been put down at half the cost in half the time.”[17]

Commissioner Taft, for his part, gave the secret police plenty to collect and report on, with his Civil Commission’s enactment, in October 1901, of a Libel Law and a Sedition Law. The first provided for a year’s imprisonment for print or speech that exposed anyone to “public hatred, contempt or ridicule.” The second law imposed a potential penalty of death for treason, seven years’ imprisonment for failing to report treason, two years for uttering “seditious words or…scurrilous libels against the Government,” and one year for advocating “the independence of the Philippine Islands.”[18] One U.S. Senator described these two laws as “the harshest…known to human statute books.”[19]

Taft and his Interior Secretary, Dean C. Worcester, were soon using these laws to ruthlessly suppress Manila newspapers (many of which were run by disgruntled U.S. Army veterans, frustrated with the transition to civilian rule and Taft’s administration of it), along with any other criticism of the political machinery that Taft and Worcester were constructing for the Philippines and, additionally, for themselves. In 1903 Taft and Worcester used their surveillance machinery to disgrace and expel an American Associated Press (AP) reporter from Manila who was promoting one-star General Leonard Wood, then stepping down as governor-general of Cuba following his heroic turn with the “Rough Riders,” to replace Taft in Manila. The apparent long-term plan was to earn General Wood a second star and perhaps eventually high public office in the United States. Taft used his surveillance machinery to build a secret dossier on the AP reporter’s somewhat unsavory past, then convinced the AP to fire him, to be replaced with a new reporter who met Taft’s approval, then tarnished Wood’s reputation back in the United States through association with the disgraced reporter. By the end of Wood’s Senate hearings on his second star, his political career was effectively over.[20] In 1910 he was named U.S. Army Chief of Staff by Taft, who in 1908 had been elected President of the United States.

Taft and Worcester used the same methods to reward and punish Filipinos who were gradually becoming integrated into the civilian government, instituting a system of political cronyism that persists in the Philippines to this day. Worcester, who believed firmly in racial evolution and believed that Filipino tribal “savages” were “the lowest of living men,” the first step in man’s evolution from “the gorilla and the orang-utan,” only associated with Filipinos who were part of a

coterie of wealthy, well-educated, fair-skinned Spanish mestizos: Benito Legarda, T.H. Pardo de Tavera, and Cayetano Arellano. While they provided him with intelligence on their fellow Filipinos, Worcester reciprocated by rewarding these ‘intimate friends of mine’ with high offices when Taft’s second Philippine Commission formed a civil government after 1900. His bitterest enemies belonged to a circle of radical Tagalog-speaking intellectuals that included Fernando Ma. Guerrero, Rafael Palma, and Mariano Ocampo. When their newspaper, El Renacimiento, mocked his racial theories in a famous ‘Aves de Rapiña’ (Birds of Prey) editorial in 1908, Worcester sued for libel, winning both a criminal conviction and a civil suit that bankrupted the journal.[21]

American visitors to Manila during this time period, such as economist Dr. H. Parker Willis, who would go on to serve as the secretary of the U.S. Federal Reserve, described U.S. rule as a “reign of terror.” All sorts of public gatherings were subject to surveillance, and Philippine society was “literally honeycombed by the secret service,” with Filipino leaders apprehensive that their own servants were “in the employ of the secret service bureau, and even wholly innocent remarks, either oral or by letter, were likely to be seized upon and distorted by detectives.”[22] How was any of this legal, under the rule of U.S. officials purportedly governed by the principles embodied in the U.S. Constitution, chief among them, freedom of expression?

First and foremost, the U.S. Supreme Court in 1901 had upheld the constitutionality of the Foraker Act imposing tariffs on Puerto Rican sugar in two of the earliest Insular Cases, DeLima v. Bidwell[23] and Downes v. Bidwell,[24] whose reasoning was then extended to the Philippines. While a number of Insular Cases had already been decided by May 1901 when the Downes decision was released, it was the Downes opinion that offered the most fulsome reasoning, such as it was, about the origin and nature of the U.S. Government’s power to govern the colonial possessions acquired from Spain in the Spanish-American War. In December 1901, the U.S. Supreme Court extended its holdings in DeLima and Downes to the Philippines in Fourteen Diamond Rings v. United States,[25] upholding a forfeiture action against a very unfortunate soldier from the First Regiment of the North Dakota United States Volunteer Infantry, who had somehow acquired through purchase or loan fourteen diamond rings in Luzon in 1899, and who apparently had expected to be able to bring them home duty-free after his tour of duty in the Philippines ended.[26]

It was Downes that the Supreme Court would cite 89 years later in Verdugo-Urquidez for the proposition that “not every constitutional provision applies to governmental activity even where the United States has sovereign power,”[27] so this decision is worth examining in some detail. Like Verdugo-Urquidez, Downes is itself a muddled plurality opinion, and to some degree can only be understood alongside DeLima, since different justices joined different concurring opinions in each of the two decisions. In the opinion delivered by Justice Brown in announcing the conclusion and judgment of the court, the following assertions were made in concluding that Puerto Rico was a U.S. territory but not “part of the United States”:

· It has long been settled law that the U.S. can acquire territory that is then administered by the U.S. Congress prior to being admitted for statehood, as was the case with regard to the 1803 Louisiana Purchase and the acquisition of Florida from Spain. The power to acquire territory “is derived from the treaty-making power and the power to declare and carry on war. The incidents of these powers are those of national sovereignty, and belong to all independent governments.”[28]

· Congress has the constitutional authority to directly administer U.S. territory; indeed, even in the Dredd Scott opinion “it was admitted to be the inevitable consequence of the right to acquire territory.”[29]

· The United States can also exercise sovereignty over territory that will never become a state; namely, the District of Columbia, which is definitely “part of the United States”[30] and yet is administered by Congress “in a double capacity: in one as legislating for the States; in the other as a local legislature for the District of Columbia.”[31]

· The United States can also “safely govern” conquered people indefinitely as a “distinct people”, as it has done with regard to Native Americans, and without extending to them all the rights guaranteed in the U.S. Constitution to U.S. citizens.[32] Indeed, “it is doubtful if Congress would ever assent to the annexation of territory upon the condition that its inhabitants, however foreign they may be to our habits, traditions and modes of life, shall become at once citizens of the United States.” The consequences would be “extremely serious” if either such conquered people or their children were entitled to all the rights, privileges and immunities of citizens “whether savage or civilized.”[33]

· The “fundamental error” of the Dredd Scott decision, the “father of all the political errors,” was “that of assuming the extension of the Constitution to the territories.”[34]

· Some Constitutional rights are “natural rights,” “enforced in the Constitution by prohibitions against interference with them” while others are “artificial or remedial rights, which are peculiar to our own system of jurisprudence.”

· In the former category are “the rights to one’s own religious opinion and to a public expression of them…the right to personal liberty and individual property; to freedom of speech and of the press; to free access to courts of justice, to due process of law and to an equal protection of the laws; to immunities from unreasonable searches and seizures, as well as cruel and unusual punishments ; and to such other immunities as are indispensable to a free government.”

· The latter category consists of “the right to citizenship, to suffrage…and to the particular methods of procedure pointed out in the Constitution, which are peculiar to Anglo-Saxon jurisprudence, and some of which have already been held by the States to be unnecessary to the proper protection of individuals.”[35]

· There is no reason to fear that an “unrestrained possession of power on the part of Congress may lead to unjust and oppressive legislation, in which the natural rights of territories, or their inhabitants, may be engulfed in a centralized despotism.” This is because “[t]here are certain principles of natural justice inherent in the Anglo-Saxon character which need no expression in constitutions or statutes to give them effect or to secure dependencies against legislation manifestly hostile to their real interests.”[36]

When asked afterwards how he interpreted the Court’s decision, Secretary of War Elihu Root responded, “as near as I can make out the Constitution follows the flag—but doesn’t quite catch up with it.”[37]

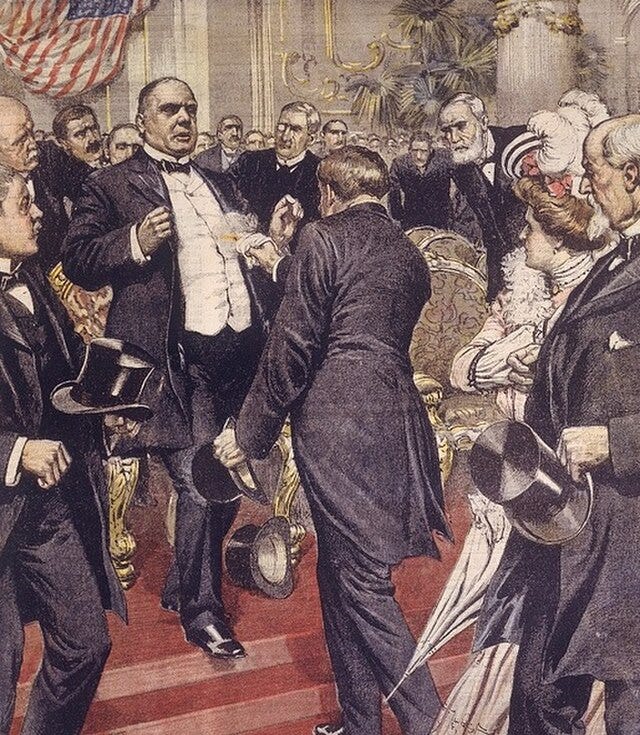

The ambiguity surrounding this bifurcated application of Constitutional rights to U.S. citizens versus U.S. subjects overseas was exacerbated by the fact that, even at home it was not at all clear how these rights applied or could be enforced. The federal government’s law enforcement and intelligence-gathering “footprint” was still so small that many of the limitations imposed on it by the U.S. Bill of Rights—particularly the First and Fourth Amendments—had never been tested. For example, after President McKinley was assassinated in September 1901 by Leon Czolgosz, an anarchist, President Roosevelt called for a “war” against anarchists and “all active and passive sympathizers with anarchists” in his first message to Congress.[38] Between 1902 and 1903, four states passed legislation to outlaw the advocacy of anarchy.[39] At the time, the Supreme Court had not extended First Amendment protections to abuses by state governments; this would not occur until 1925.[40]

At the federal level, the United States furthered the war against anarchists via its first-ever immigration law to regulate belief. Even though Czolgosz was a U.S. citizen, in March 1903 Congress enacted a law that barred from the U.S. immigrants who “believe in or advocate the overthrow by force and violence” of the U.S. governments, or all governments, or all forms of law, or the assassination of public officials, or who “disbelieve in” or oppose all organized government. Any individual developing such views after arriving in the U.S. was also deportable within three years of entry.[41] The law was upheld by the Supreme Court in Turner v. Williams, which addressed the First Amendment objection as follows:

We are at a loss to understand in what way the act is obnoxious to this objection. It has no reference to an establishment of religion, nor does it prohibit the free exercise thereof; nor abridge the freedom of speech or of the press; nor the right of the people to assemble and petition the government for a redress of grievances. It is, of course, true that if an alien is not permitted to enter this country, or, having entered contrary to law, is expelled, he is in fact cut off from worshipping or speaking or publishing or petitioning in the country; but that is merely because of his exclusion therefrom. He does not become one of the people to whom these things are secured by our Constitution by an attempt to enter, forbidden by law.[42]

Personal vice was another area where its regulation and enforcement in the Philippines under Taft tracked with emerging practices in the United States during what is now known as the Progressive Era (1900-1918), starting with efforts to regulate opium. At the time that ownership of the Philippines passed from Spain to the United States, there were hundreds of state-licensed opium dens generating “a substantial $500,000 in tax revenues from opium auctions open only to Chinese.”[43] American Protestants, who had missionaries in the Philippines, heavily lobbied the White House to outlaw opium entirely, and in 1908, with strong support from Manila’s clergy and Chinese community, they succeeded.[44] Opium imports were then banned from the United States, except for medicinal purposes, in 1909.[45]

The criminalization of prostitution followed a similar trajectory. In both the United States and the Philippines, there were few if any legal prohibitions on prostitution prior to the Progressive Era. The late 19th century had gradually seen an increase in demand globally for prostitution amid Westernization, the transportation revolution, migration to large cities, and militarization, which “created all-male populations that could support large numbers of prostitutes.”[46] This was certainly the case in the Philippines, where the U.S. colonial regime’s “ambiguous attitude toward prostitution made it a staple of the metropolitan vice economy. As soon as American soldiers and sailors marched into Manila, a ‘flood of cosmopolitan harlotry’ followed from ports around the Pacific.”[47] By 1915, the red-light district in Manila “had nearly a hundred houses filling a full city block…with every occupant licensed by the police and inspected by the Bureau of Health.”[48]

But back in the United States, as well as in Europe, concerns had been emerging since the turn of the century about the scourge of “white slavery.”[49] In 1910, the U.S. Congress passed the White Slave Traffic Act (known as the Mann Act after its sponsor), making it a crime to transport “any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.”[50] In the Philippines, Governor-General W. Cameron Forbes, “acting on the belief that white prostitutes diminished the dignity of his race, expelled all women from [Manila’s red-light district] by 1912.”[51]

Finally, gambling attracted the attention of the reformers. In the United States, lotteries had begun to fall under state scrutiny in the late 19th century in large part because so many of them were corrupt, with organizers sometimes absconding with the proceeds across state lines. Accordingly, in 1890, the U.S. Congress had banned the interstate promotion and sale of lottery tickets, and then banned the use of the U.S. mail to sell lottery tickets in 1894.[52] In the Philippines, the Spanish had tried and mostly failed to eradicate gambling through “limited licensing and failed policing” of a disproportionately Chinese population playing panguingue and fan-tan, but also a Spanish contingency that enjoyed monte, horse racing, cockfighting, and a low-cost lottery called jueteng, which paid out a jackpot of five hundred Mexican dollars. Between the opium dens, the prostitutes, the horse tracks and the casinos, U.S. Army troops who occupied Manila after 1898 had no shortage of diversions.[53] But even Filipino nationalists like Jose Rizal believed that cockfighting and other vices were holding back Filipinos as a race,[54] and in 1907, the Philippine Commission, under pressure from multiple quarters, “suddenly adopted a string of legal prohibitions: Act No. 1761 restricting and then banning opium; Act No. 1773 making adultery, along with rape and abduction, ‘public crimes’ exempt from private settlement; and, most ambitious, Act No. 1757, prohibiting most forms of gambling.” Even after Filipino national leaders began taking over the legislature and Philippines Supreme Court from American authorities in 1907, they “embraced this coercive approach to morality and equated gambling with racial degeneration.”[55]

The immediate effect of criminalizing vice was an explosion of organized crime syndicates, police activity, and along with it, widespread police corruption. At the end of Spanish rule, the ratio of police to residents in Manila had been 1:912. Within the first five months of establishing Manila’s civil government in 1901, the newly structured Manila Metropolitan Police force consisted of 300 first-class American patrolmen, 360 Filipino third-class patrolmen, and 24 secret service detectives, with authority to regulate all public morals, including gambling, pool halls, opium dens, and any “indecent or obscene” display.[56] By 1926, the city’s ratio of one policeman per 400 residents was double Bombay’s 1:972, comparable to that of New York or London but controlled and funded by the U.S. federal government. Many of these poorly paid police “were supposed to arrest influential social superiors or powerful syndicate bosses but instead opted for a well-paid symbiosis with syndicated vice. One veteran police observer, Maj. Emanuel Bajá, estimated in 1933 that “the opium, gambling, and firearm laws” accounted for over 95 percent of ‘all recorded cases of corruption in our police system.’”[57] As for prostitution, Mayor Justo Lukban of Manila tried closing the entire red-light district in 1918 “in a burst of outrage,” but just two years later, it came roaring back, now with “over six hundred small brothels, unregulated and under the informal control of the corrupt police.”[58]

Between the Manila police vice squads, the tabloid journals and the intelligence-gathering on both Filipino and U.S. political leadership, the Philippines offered a potent mix of political repression, corruption and scandal, a pattern that persists in the Philippines to this day. By 1903, between 75% and 90% of American policemen already had Filipina mistresses (queridas) who expected protection for their relatives.[59] After the opium ban went into effect, the wife of Assembly Speaker Sergio Osmeña, Estefania Chiong Veloso, “boldly, even brazenly used her husband’s influence to continue the family business of supplying Cebu’s opium addicts.” She often personally accompanied her shipments, and if her convoy encountered a constabulary checkpoint, she would threaten the soldiers with the loss of their jobs if they attempted to search her trucks, holding a lantern up to her face “to be sure that they recognized who she was.”[60]

U.S. colonial authorities could use the information on vice and “indiscretion” that was constantly being gathered on public figures to pick and choose which Filipino leaders to elevate.

In the cases of Sergio Osmeña and his frequent political rival, Manuel Quezon, U.S. colonial authorities overlooked or even suppressed salacious or damaging information about them, as they were seen as moderates compared to the more militant nationalists who continued to challenge U.S. authority. Those radicals in the latter category “faced constant surveillance and endless prosecutions that first broke and then reformed them as agents of the colonial state…The shift from revolutionary nationalism to patronage politics in the first decade of U.S. rule was not simply a natural response to its ‘policy of attraction’; it was influenced by secret police manipulation of sensitive information for effects ranging from disinformation to demoralization.”[61]

All of these manipulative tools being used by U.S. authorities in the Philippines were being repeatedly endorsed by the U.S. Supreme Court as it continued to issue opinions in the Insular Cases. Dorr v. United States,[62] for example, revolved around a series of tabloid articles published in Manila starting in 1902 regarding Commissioner Benito Legarda’s alleged affair with his young stepdaughter. Because Legarda was a close political ally of both Taft and Worcester, Taft replaced a judge who had initially ruled against Legarda in his libel complaint, and then recruited a tough attorney from Michigan to pursue criminal libel charges, eventually obtaining criminal convictions and six-month prison sentences against the owner of the newspaper Manila Freedom, Fred L. Dorr, and his editor Edward O’Brien.[63] By 1904, when the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court on appeal from the Supreme Court of the Philippine Islands, DeLima and Downes had already established that not all Constitutional rights applied in the Philippine Islands. In Dorr, the Supreme Court decided that trial by jury was not among the rights that needed to be applied, as at the time the United States acquired the Philippines from Spain, “the civilized portion of the islands had a system of jurisprudence founded upon the civil law [which provided for trial by judge], and the uncivilized parts of the archipelago were wholly unfitted to exercise the right of trial by jury.”[64] The convictions were affirmed.

The Court reached a similar result in 1914 in Ocampo v. United States,[65] against the owner and staff of the newspaper El Renacimiento, who allegedly had libeled Worcester in 1908 and were thereafter arrested, tried convicted and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment, without a preliminary investigation or a finding of probable cause, as such requirements had been eliminated in 1903 by the Philippine Commission with respect to the City of Manila, allowing the Prosecuting Attorney of the City of Manila to obtain arrest warrants based solely on his own investigation and examination of witnesses.[66] On appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court, the plaintiffs in error argued that the process violated the Philippine Bill of Rights, a statute enacted by the U.S. Congress the year after DeLima and Downes that provided, inter alia, that “no law shall be enacted in said islands which shall deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law or deny to any person therein the equal protection of the laws,” and that “no warrant shall issue but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation.”[67] The Court rejected their appeal, noting that “Section 5 of the act of Congress contains no specific requirement of a presentment or indictment by grand jury, such as is contained in the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution of the United States. And in this respect, the Constitution does not, of its own force, apply to the Islands.”[68]

In the “proper” United States, Constitutional rights took a different path that same year with regard to the warrant requirement in the 4th Amendment, as law enforcement activity increased around federal criminalization of the lottery.

While the U.S. Marshals were still few in number, state and local police “deputized” by U.S. Marshals could carry out searches and arrests in furtherance of federal law. On December 21, 1911, a group of unnamed state and/or local police in Kansas City, Missouri, broke into the home of Freemont Weeks, searching and seizing all of his “books, letters, money, papers, notes, evidences of indebtedness, stock, certificates, insurance policies, deeds, abstracts, and other muniments of title, bonds, candies, clothes, and other property in said home” and taking them to the U.S. Marshal.[69] Weeks was then arrested without warrant by “a police officer” at his place of employment, and charged, tried and convicted, based on evidence seized in his home, of using the U.S. mail to transport lottery tickets.[70] At trial, he repeatedly petitioned for the return of his property and was denied. He argued before the Supreme Court that the court erred both in the refusal to return his property and in allowing the papers to be used at his trial, in violation of both the Fourth and Fifth Amendments.[71]

At the time, use of documentary evidence in criminal trials was still relatively rare compared to witness testimony.[72] However, the Constitution’s Framers and early interpreters generally found that individual property rights “trumped any interest the government had in property for use as mere evidence in court cases…Personal property rightfully belonging to a defendant could never be taken from him without due process and then introduced at his criminal trial.”[73] Indeed, the “mere evidence rule” providing as such had existed in English law dating back at least to 1763, in two cases that continue to have a tremendous continuing influence on U.S. law.[74] In Weeks, the Supreme Court observed that “a man's house was his castle, and not to be invaded by any general authority to search and seize his goods and papers.”[75] Because the trial court “should have restored these [papers] to the accused,” which had been taken “by an official of the United States, acting under color of his office, in direct violation of the constitutional rights of the defendant…we think prejudicial error was committed.”[76] The overturning of Weeks’ conviction based on the rejection of evidence obtained in violation of the Constitution came to be known as the Exclusionary Rule. Rene Verdugo-Urquidez would one day invoke the Exclusionary Rule in seeking to exclude evidence from his U.S. court proceeding that had been seized without a warrant in Mexico.

[1] Paul Kramer, “The Water Cure,” The New Yorker, February 17, 2008, available at https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2008/02/25/the-water-cure (viewed October 24, 2024).

[2] A True Relation of the late unjust, cruel and barbarous proceedings against the English at Amboyna. British Library: John Skinner of the East India Company. 1624.

[3] Paul Kramer, “The Water Cure.”

[4] Robert Justin Goldstein, Political Repression in Modern America, at 60.

[5] Paul Kramer, “The Water Cure,” The New Yorker.

[6] Paul Kramer, “The Water Cure,” The New Yorker.

[7] Paul Kramer, “The Water Cure,” The New Yorker.

[8] Quoted in Edmund Morris, Theodore Rex (The Modern Library: New York, 2001), at 98.

[9] Bartholomew H. Sparrow, The Insular Cases and the Emergency of American Empire (University Press of Kansas, 2006), at 37.

[10] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 76-77.

[11] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 77-78.

[12] See Gregory McNeal, “Kill List Baseball Cards and the Targeting Paper Trail,” The Lawfare Institute, February 26, 2013, available at https://www.lawfaremedia.org/article/kill-list-baseball-cards-and-targeting-paper-trail (viewed November 2, 2024); Kaitlin Flanigan, “DHS Officials Called Arrested Protester Reports ‘Baseball Cards’: Review,” KOIN, October 1, 2021, available at https://www.koin.com/news/protests/us-department-homeland-security-intelligence-analysis-team-2020-protests-portland/ (viewed November 2, 2024).

[13] The dramatic story of Aguinaldo’s capture is told in Howard A. Giddings, Exploits of the Signal Corps int eh War with Spain (Kansas City, MO: Hudson-Kimberly Publishing Company, 1900), at 115-23, available at https://archive.org/details/exploitsofsignal00gidd (last viewed November 27, 2024). It was re-told, and Giddings’ account quoted extensively, in Book VI of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities, United States Senate (“Church Committee Report”), U.S. Government Printing Office, 1976.

[14] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 82-83.

[15] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 83.

[16] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 105.

[17] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 104-05.

[18] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 99.

[19] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 96 (citing to United States, Debate in the Senate of the United States, February 6, 1902, on the Philippine Treason Law (Washington, DC 1902), at 8).

[20] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 115-21.

[21] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 101.

[22] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 104.

[23] 182 U.S. 1 (1901). De Lima held that Puerto Rico had ceased to be a foreign territory and that duties were no longer collectible upon merchandise brought into the United States from Puerto Rico. In Downes, the Supreme Court was asked a slightly different question, which was whether Puerto Rico became a part of the “United States” with regard to Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution, which provides that “all duties, imposts and excises shall be uniform throughout the United States.” Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution provides that “vessels bound to or from one State” cannot “be obliged to enter, clear or pay duties in another.” Downes v. Bidwell, 182 U.S. at 248-49.

[24] 182 U.S. 244 (1901). Other early Insular Cases that preceded Downes included Goetze v. United States, 182 U.S. 221 (1901)(tariffs on imports from Hawai’i); Dooley v. United States, 182 U.S. 222 (1901)(tariffs on Puerto Rican imports); and Armstrong v. United States, 182 U.S. 243 (1901)(duties on Puerto Rican goods).

[25] 183 U.S. 176 (1901).

[26] As noted in the decision, he had acquired the rings sometime after the ratification of the treaty of peace between the United States and Spain in February 1999 and the proclamation thereof by President McKinley on April 11, 1999, which apparently led him to believe that the Philippines were now “part of the United States.” Nonetheless, when he arrived in Chicago in May 1900, the “rings were seized by a customs officer as having been imported contrary to law, without entry, or declaration, or payment of duties, and an infomraiton was filed to enforce the forfeiture thereof.” 183 U.S. at 177.

[27] United States v. Verdugo-Urquidez, 494 U.S. at 268.

[28] 183 U.S. at 268.

[29] 182 U.S. at 250, 254-56, 266.

[30] 182 U.S. at 259-62.

[31] 182 U.S. at 259-60, citing Loughborough v. Blake, 5 Wheat. 317.

[32] 182 U.S. at 281, citing Johnson v. McIntosh, 8 Wheat. 543 (holding that Native Americans cannot sell their land to private individuals).

[33] 182 U.S. at 279.

[34] 182 U.S. at 276 (quoting a history of the Dredd Scott case written by a “Mr. Benton.”)

[35] 182 U.S. at 282-83 (citing Minor v. Happersett, 21 Wall. 162).

[36] 182 U.S. at 280.

[37] Quoted in Kal Raustiala and Philip C. Jessup, Elihu Root [GET FULL CITE.]

[38] Robert Justin Goldstein, Political Repression in Modern America, at 65.

[39] Robert Justin Goldstein, Political Repression in Modern America, at 68.

[40] Gitlow v. New York, 268 U.S. 652 (1925)(overturning New York’s Criminal Anarchy Law, extending First Amendment protections via the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment).

[41] Robert Justin Goldstein, Political Repression in Modern America, at 67-68.

[42] 194 U.S. 279 (1904), at 294.

[43] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 148.

[44] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 149-50.

[45] Public Law No. 221, 60th Congress, approved February 9, 1909. An Act to prohibit the importation of and use of opium for other than medicinal purposes. Reproduced in Opium and Narcotics Laws, Compiled by Gerard P. Walsh, Jr., U.S. Government Printing Office (Washington: 1981), available at https://www.ojp.gov/ncjrs/virtual-library/abstracts/opium-and-narcotic-laws (viewed November 7, 2024).

[46] Ruth Rosen, The Lost Sisterhood: Prostitution in America, 1900-1918 (Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore and London, 1982), 4.

[47] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 243.

[48] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 244.

[49] Ruth Rosen, The Lost Sisterhood: Prostitution in America, 1900-1918 (Johns Hopkins University Press: Baltimore and London, 1982), 15.

[50] Legal Information Institution, “Mann Act,” Cornell Law School, available at https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/mann_act (viewed November 11, 2024). The current version of the statute reads in relevant part, “Whoever knowingly transports any individual in interstate or foreign commerce, or in any Territory or Possession of the United States, with intent that such individual engage in prostitution, or in any sexual activity for which any person can be charged with a criminal offense, or attempts to do so, shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than 10 years, or both.” 18 U.S.C. 2421(a).

[51] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 244.

[52] Scott Neuman, “The settlers brought the lottery to America. It's had a long, uneven history,” National Public Radio (NPR), August 9, 2023, available at https://www.npr.org/2023/08/09/1192893936/mega-millions-powerball-lottery-history-in-america (viewed November 11, 2024).

[53] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 152-53.

[54] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 153 (citing Jose Rizal’s 1886 novel Noli Me Tangere).

[55] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 155.

[56] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 241-42.

[57] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 245.

[58] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 244.

[59] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 245.

[60] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 151.

[61] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 204.

[62] 195 U.S. 138 (1904).

[63] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 113-14.

[64] 195 U.S. at 145.

[65] 234 U.S. 91 (1914).

[66] Cited in Ocampo, 234 U.S. at 97. Act No. 612 provided that, “In cases triable only in the Court of First Instance in the City of Manila, the defendant shall have a speedy trial, but shall not be entitled as of right to a preliminary examination in any case where the prosecuting attorney, after a due investigation of the facts, under § 39 of the act of which this is an amendment [Act No. 183], shall have presented an information against him in proper form: Provided, however, that the Court of First Instance may make such summary investigation into the case as it may deem necessary to enable it to fix bail or determine whether the offense is bailable.” Quoted in id.

[67] 234 U.S. at 94-95 (citing Act of July 1, 1902, § 5, c. 1369, 32 Stat. 692).

[68] 234 U.S. at 98 (citing Hawaii v. Mankichi, 190 U. S. 197; Dorr v. United States, 195 U. S. 138; Dowdell v. United States, 221 U. S. 325, 221 U. S. 332).

[69] 232 U.S. at 387.

[70] 232 U.S. at 386.

[71] It is not at all clear from the Weeks opinion whether the Court considered its finding to flow from the Fourth or the Fifth Amendment. As Roots points out, the Fifth Amendment’s exclusionary remedy is “explicit and unchallengeable”—“No person…shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself.”

[72] Roger Roots, “The Originalist Case for the Fourth Amendment Exclusionary Rule,” 45 Gonzaga L. Rev. 1 (2010), at 6.

[73] Roger Roots, “The Originalist Case for the Fourth Amendment Exclusionary Rule,” 45 Gonzaga L. Rev. 1 (2010), at 36-37.

[74] See Wilkes v. Wood, 98 Eng. Rep. 489 (1763) and Entick v. Carrington, 19 How. St. Tr. 1029 (1765).

[75] 232 U.S. at 390.

[76] 232 U.S. at 398.