Race riots, Christmas and pogroms

Part II.C of my book: Read to the end for a special Christmas video! (I promise it will make you feel better)

C. The Imperialist Road to Versailles

White Americans might have thought that they could dabble in European-style imperialism in the Far East while keeping their government small, their home front peaceful and their civil liberties safe from European covert intrigues and entanglements. As the lead up to World War I makes clear, in reality, they never stood a chance. They had been entangled by choice in their decision to acquire the Philippines, whose territory was now a part of “the United States” even if its people were not. The Philippines’ uniquely tortured legal status, as set forth in the Insular Cases, quickly became an unexpected conduit for the lawful immigration of Indians into the U.S. mainland amid white resistance. This in turn forced the United States to make common cause with British imperialist goals and the burgeoning British intelligence apparatus, which extended not just to the Pacific region but, of course, throughout India, the Mediterranean (controlled through the Suez Canal), and increasingly, Ottoman-controlled Arab lands, chief among them Palestine. The United States’ lack of an overall intelligence apparatus, which still trailed behind its European counterparts, made both its citizens and its elected leaders susceptible to covert foreign influence, particularly by the British. After the Versailles Conference of 1919, the United States would never be disentangled again.

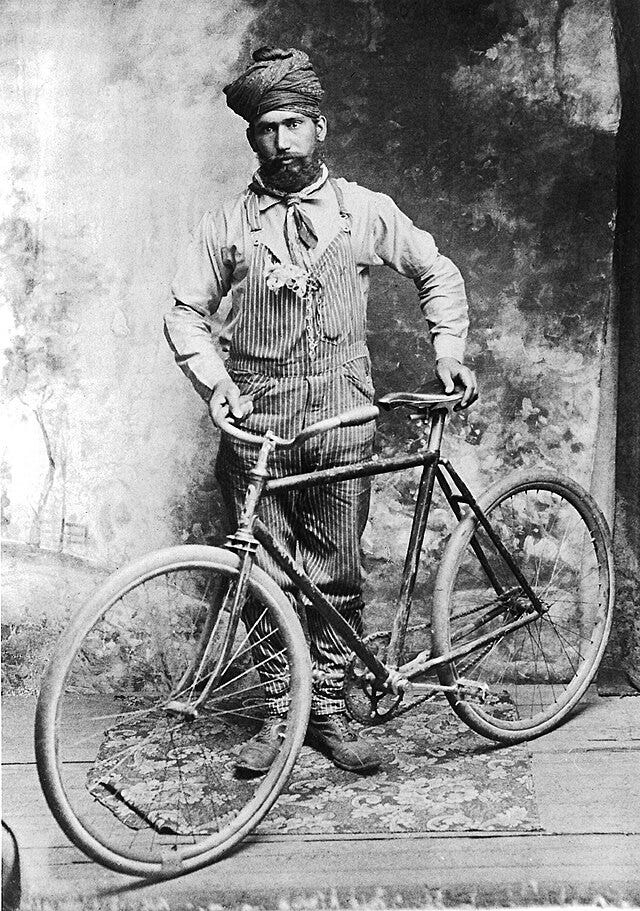

Hindu and Sikh migrants from India began showing up in the Pacific Northwest in the early 20th century, primarily seeking economic opportunity in the lumber yards and fleeing desperate poverty at home. Activist Ram Chandra attributed Indian poverty to British colonial policies on Indian handicrafts, opining, “Manchester allows no rivalry from Hindu weavers…the great industrial prosperity of England from the eighteenth century onward, owes its being to the stolen wealth and broken industries of India.”[1] For Punjabis, the single most important employer outside of their native area was the British Indian army—Punjabi Sikh soldiers were essential to the repression of the 1857 mutiny in India—and by the turn of the 20th century many Sikhs had served as soldiers and police officers across East Asia and were settling in British Columbia, Washington State, Oregon and California.[2]

Anti-colonial Indian intellectuals also found that being based in the United States guaranteed them the freedom under the First Amendment to organize and publish global newsletters; in India, by contrast, the Prevention of Seditious Meetings Act prohibited any public meeting “likely to promote sedition or to cause a disturbance of domestic tranquility.”[3] In New York, Irish-Americans like George Freeman provided funding and support to Indian nationalists; in 1908 the UK Department of Criminal Intelligence (DCI) reported that the first two issues of Taraknath Das’ publication Free Hindustan had arrived in India concealed inside a copy of the Gaelic American.[4]

But the Indian workers were receiving a hostile reception from their white counterparts on the Pacific Coast. The territory of Oregon had been founded as an explicitly white man’s land; in 1844, it had banned Black people outright from settling there, and until 2002, the Oregon state constitution barred “negros, mulattos and Chinamen” from owning land in the state.[5] In September 1907, a wave of anti-Asian race riots throughout the region culminated in an attack on Indian lumber workers in Bellingham, Washington, by a mob of 200 white men who dragged them out of the barracks where they slept, threw their belongings into the streets and warned them to leave town at once. The Indians made their way on foot to Vancouver, British Columbia, only to be faced two days later by the largest race riot in the history of Canada. The riots had both begun as rallies organized by the trans-border Asiatic Exclusion League.[6]

The anticolonial agitators in New York and the migrant workers on the Pacific Coast eventually made common cause, and with the assistance of immigration attorneys, began systematically testing the boundaries of both U.S. and Canadian immigration law. Indian migrant labor was generally welcomed in both the Philippines and Hawai’i. Thus, Indian migrants arriving in Seattle and San Francisco from the Philippines and Hawai’i in 1910 insisted that, because they had traveled from one part of “the United States” to another, they had already been admitted to the U.S. mainland.[7] West Coast U.S. immigration authorities, having no clear basis to deport them but facing considerable pressure from local white organized labor to do exactly that, began informally collaborating with a British spy hired by the Canadians and his network of Indian informants,[8] perhaps the earliest precursor to what today is known as the “Five Eyes.” Between 1911 and 1914, this collaborative group of officials tried unsuccessfully to deport Taraknath Das and prevent him from becoming a naturalized U.S. citizen by proving he was an anarchist. They also tried to invoke the U.S. Naturalization Law of 1790, which allowed naturalization to only “free white persons,” to which Indians retorted that, scientifically, they were of the Caucasian race.[9]

By the fall of 1913, Indians on the West Coast had formed the Ghadar (Mutiny) Party and were actively organizing for a military rebellion against British rule.[10] The Party offered its recruits military training that included rifle and revolver shooting in the hills behind the campus of the University of California at Berkeley, which enrolled many young promising Indian revolutionaries.[11]

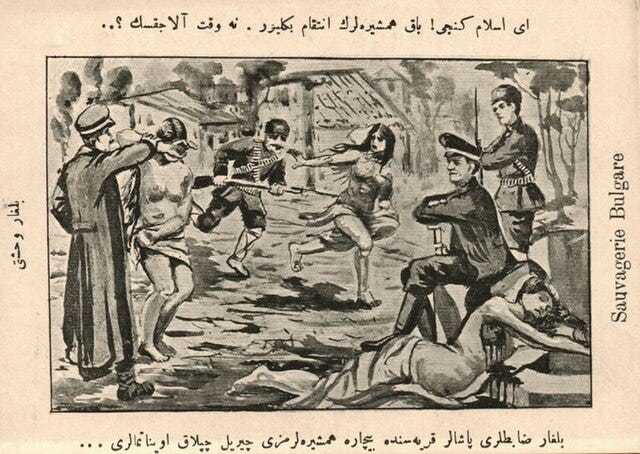

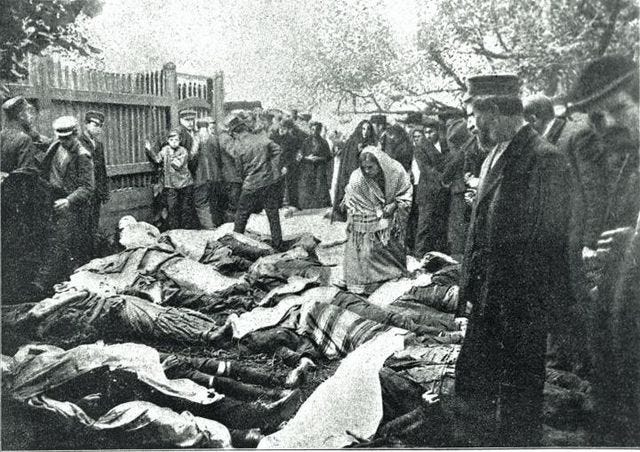

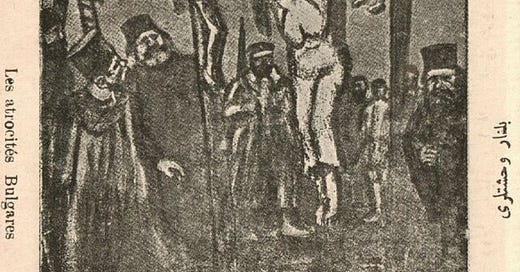

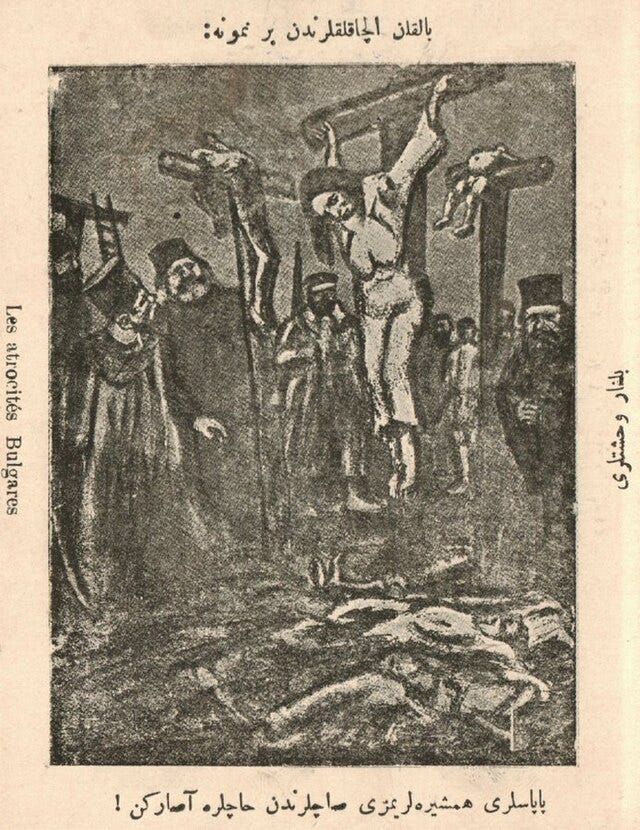

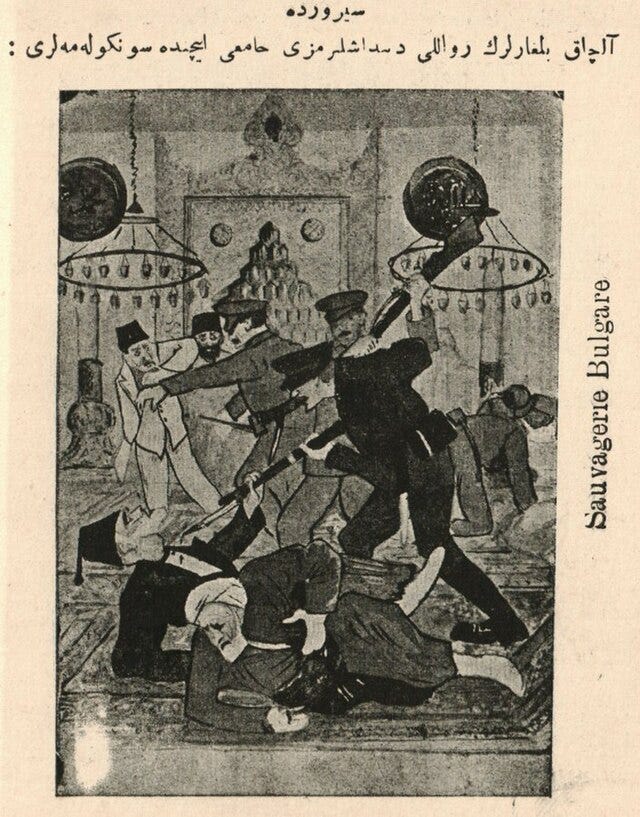

Half a world away, the Ottoman Empire was in its death throes following a century’s worth of European nationalism and incessant demands for legal reform gradually eroding the very concept of a multi-ethnic empire. The trend towards national sovereignty based solely on ethno-religious homogenization had started with the Greek revolution in 1832, after which Greek mobs engaged in the wholesale rape, butchery and expulsion of every Muslim man, woman and child left in the territory.[12] Following riots in the Balkans, Russia declared war on the Ottoman state in 1877, reaching the gates of Istanbul “just ahead of a massive flood of Muslim refugees fleeing from the massacres against civilians.”[13] The European Great Powers then established a new status quo in the Balkans that involved Austrian occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina.[14]

In 1908, the “Young Turks” overthrew the sultan and tried to establish an Ottoman constitutional government along European lines, centralizing authority and the education system, insisting on equality before the law, and stressing Turkish as the official language. This enraged the Greek Orthodox Church and other domestic religious groups. Before the Young Turks could fully focus on domestic reforms, the Austro-Hungarian Empire outright annexed Bosnia, and Bulgaria declared its independence from Ottoman rule.[15] The annexation of Bosnia heightened tensions between the Austrians and Serbian nationalists, the latter of whom laid their own Slavic ethno-religious claim to Bosnia-Herzegovina, an ambition in which they were supported by the Russians.[16]

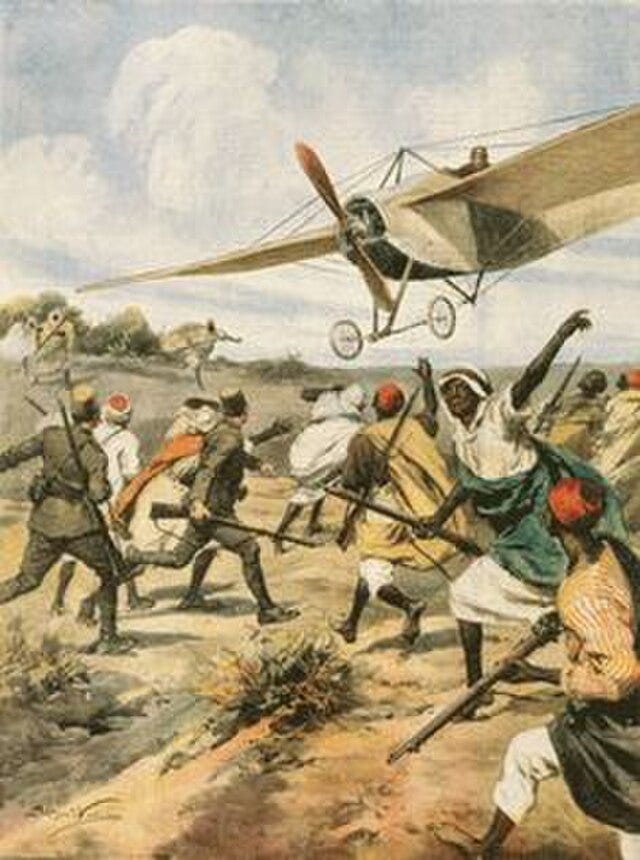

Then in 1911, Italy, in its bid to prove its status as a Great Power, invaded Libya and defeated Ottoman forces there, with the support of wealthy Muslim and Jewish merchants in Tripoli who had been marginalized by the Young Turks.[17]

This further demonstrated Ottoman military weakness and forced it to divert resources from Macedonia, which then led to the Balkan Wars of 1912-13. The Ottomans were again decisively beaten by the new Balkan League consisting of Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro and were forced to withdraw from Europe entirely. In the Arab press, from Egypt to Lebanon, daily reports “described mosques and schools rapidly becoming crammed with hundreds of hungry men, women, and children forced from their homes in the lost Balkan provinces. ‘Disastrous calamity’ (nakba fatika) was one of the prevailing labels given to the Ottoman defeat.”[18]

The restoration of Christian sovereignty in Europe, it turns out, did not result in a new era of Christian harmony. On June 28, 1914, Austrian Archduke Francis Ferdinand, in Sarajevo to participate in military maneuvers in Bosnia, was assassinated by Serbian nationalists. Austria took the opportunity to declare war on Serbia in retribution. Serbia suggested that their differences be arbitrated by the Great Powers (France, Germany, Great Britain, and Russia).

Germany, however, had its own plans; frustrated in its efforts to achieve naval supremacy over Britain and establish colonies in the Pacific, it formed an alliance with Austria-Hungary and declared war on France and Russia. After Germany invaded Belgium in August 1914, Britain entered the war pursuant to its alliance with Belgium and France. By September 1914, the Entente (Britain and France) had stopped the German advance into France at the Battle of the Marne, at which point the two sides settled into the intractable trench warfare that would come to typify the conflict as it played out on the Western Front in Europe.

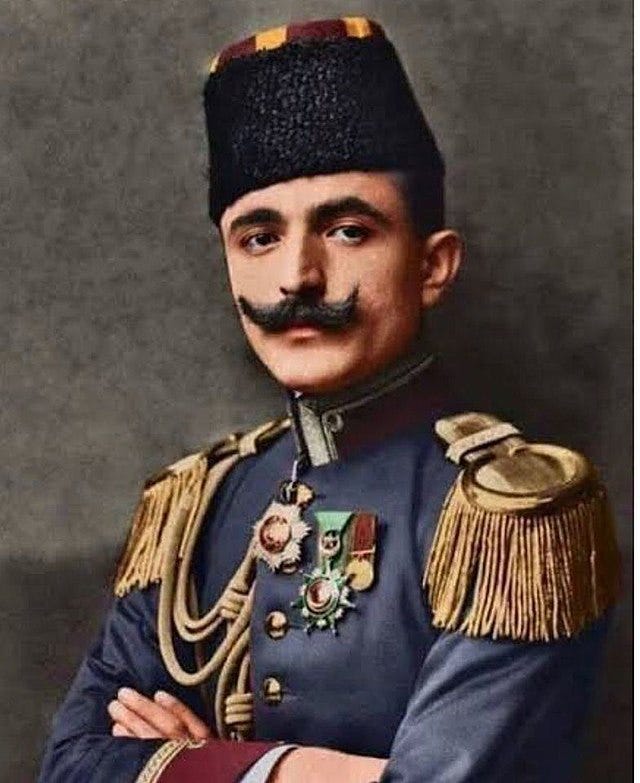

The Ottoman Empire aligned itself with Germany, guaranteeing free passage for the Germans through its own territory and into British colonial holdings in Afghanistan, India, and elsewhere, in order to subvert Russian long-term designs on the Dardanelles and in exchange for Germany’s help modernizing its military, which had been exhausted by the wars in the Balkans and Libya. The Ottoman sultan also invoked his authority as caliph to call upon all the world’s Muslims to make holy war against his enemies—including Muslims in British India.[19] Aware of how many different ethnic groups under Ottoman rule had already been collaborating with the espionage organizations of the Entente for years—Greeks, Armenians, Jews, Serbians, Bulgarians, Wallachians, Arabs and some Albanians—the Ottomans had created their own espionage and counter-espionage organization, the Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa (Special Organization), chaired by Enver Pasha. The Teşkilat-ı Mahsusa called specifically for a jihad among Muslims who had suffered under centuries of Russian rule, but such efforts were quickly crushed by the Russian Army, with the Armenians quite obviously providing assistance to the Russians at every turn.[20] American missionaries were among the firsthand witnesses to the Ottoman massacres of Armenians that followed.

Meanwhile, the Ghadar Party in San Francisco decided this was the moment to return en masse to India, spread rebellion in every corner of the land, and recruit military soldiers away from the British army.[21] The Party found an enthusiastic partner in the German intelligence and foreign policy apparatus, which consisted of a section of the German Army’s General Staff called the IIIrd Oberquartiermeister, or “IIIb,” that largely served as its intelligence bureau; and a section of the Foreign Office called the Nachrichtenstelle für den Orient or Intelligence Bureau of the Orient (NfO). The NfO was led by orientalist, archaeologist and diplomat Max Freiherr von Oppenheim, who initially developed a special strategy for "incitement" in Muslim areas that was soon expanded to include other colonies and areas under British, French or Russian rule.[22]

One offshoot of the party that included Taraknath Das made its way to Berlin and began meeting regularly with German officials, eventually persuading the Foreign Minister, Alfred Zimmerman, to send instructions to his ambassador in the United States to provide arms and funds to the Ghadar Party.[23] The military attaché to the German ambassador to the United States, Franz von Papen, later said of this joint endeavor, “we did not go so far as to suppose that there was any hope of India achieving her independence through our assistance, but if there was any chance of fomenting local disorders we felt it might limit the number of Indian troops who could be sent to France and other theatres of war.”[24] The “Berlin India Committee” supported by the NfO was followed by committees of Persian, Egyptian, Georgian and Irish nationalists.[25]

With the Ottoman Empire aligned with Germany, it was only logical for the British and French to make common cause with Arab nationalist leaders in the Levant and Arabian Peninsula who had been drifting away from loyalty to the Ottomans, due in part to the European-inspired policies of the Young Turks, which included not only civil law and educational reform, but the emancipation of women.[26] Some Arabs believed that the relative decline of the Ottoman Empire in relation to the Christian West was due to Muslims corrupting and abandoning “the true Islam,” the Islam of their ancestors, who were Arab and not Turkish.[27] Sharif Hussein of Mecca, a direct descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, was one of many such leaders whom the British thought might be able to blunt the sultan’s call for holy war. Hussein laid claim not only to the Arabian peninsula but Syria, Iraq and Palestine as well, a claim that the British initially did not take seriously.[28]

Other Arabs believed that the Ottoman Empire could still be reformed and formed various reform committees that the Young Turks then repressed, prompting the reformers to relocate to British-controlled Cairo and to Paris, where the First Arab Congress was held in 1913. Activist and reformer ‘Abd Al-Hamid Al-Zahwari explained to the newspaper Le Temps that the Arabs were holding the conference after recent Ottoman defeats in Europe in order to mitigate the negative effects on the Arab population, who were numerically the majority of the Ottoman Empire.[29] The French decided to quietly expand their influence into Syria, to which they laid a “hereditary” claim dating back to the Crusades, and whose silk industry was coveted by a powerful business lobby based in Marseilles and Lyon.[30] In June 1914, French diplomat François Georges-Picot, upon receipt of an Arab leaflet demanding independence for Syria, secretly arranged for the Greek government to provide rifles and ammunition to Christians in Lebanon, seeking to blunt British long-term designs on the region.[31]

Long wary of the potential for a Turkish advance on the Suez Canal and of German railways being built within Ottoman lands, the British War Office had already established a local intelligence network using Bedouins as spies to keep tabs on the Turkish army presence in Syria. Between 1913 and 1914, the British conducted their own local survey as the Palestine Exploration Fund, using the archaeologists Leonard Wolley and T.E. Lawrence as cover.[32]

At the outbreak of hostilities, the British sent an Indian army force to seize the oil refineries in southern Persia as well as the port city of Basra, in what is now Iraq.[33] The Entente additionally tried to seize control of the Ottoman straits that connected the Ottoman Empire to its eastern territory in the Black Sea, but following a costly amphibian landing on the peninsula of Gallipoli, they abandoned the effort.

Georges-Picot made his way to London in August 1915 to see if he could get the British government to formally agree to dividing up the Levante—still under Ottoman control—in a way that would give the French free reign in Syria, convincing his British interlocutor, the relatively inexperienced Mark Sykes, to agree in January 1916 to ceding control to France of everything north of a line running from Acre to Kirkuk, with Britain controlling everything south of that line. When informed of the Sykes-Picot agreement, the British head of military intelligence complained that “we are rather in the position of the hunters who divided up the skin of the bear before they had killed it.”[34] Other British officials wondered whether there was some way for them to circumvent the spread of French influence in the Levante over the longer term. Home Secretary Herbert Samuel had a suggestion, which he had circulated to the Cabinet in early 2015 as a memorandum entitled The Future of Palestine: what if a Jewish state could be created in Palestine under British control? This would not only blunt French designs on the region but might be a useful vehicle for pulling the United States into the war on the side of Great Britain.

The people of the United States at that time had a mix of sentiments towards the Entente allies and their opponents, the Central Powers, in part because the Entente included Russia. Prior to 1881, more than half of all Jews globally lived under Russia’s rule, most of them confined to an area approved for them called the Pale of Settlement. However, two major pogroms had then been perpetrated against Russian Jews, the first between 1881 and 1884. In Russian-controlled Warsaw, a pogrom erupted in 1881 during a Christmas service. Russia conducted a comprehensive census in 1897, using the tabulation machine that Herman Hollerith had sold to Czar Nicholas II the previous year,[35] and learned that 4,899,300 Jews were still living in the Pale of Settlement. A second pogrom followed, between 1903 and 1906. Each pogrom had precipitated the large-scale emigration of Russian Jews seeking refuge elsewhere.

Many of them settled in Palestine, where as early as the 17th century, Nathan of Gaza, a Jewish writer based in Palestine, had been trying to convince the world’s Jews to return to and restore the ancient nation of Israel; for centuries, such ideas tended to gain traction globally when they followed closely on the heels of expulsions and persecution in Europe.[36] Starting in 1897, the modern concept of Zionism pioneered by Austro-Hungarian Theodor Herzl had been the subject of a series of world Zionist Conferences, and in 1903, Herzl briefly considered a British offer to create a Jewish homeland in Uganda, as little progress had been made establishing Jewish control over Palestine.[37]

In the meantime, however, most of those fleeing the Russian pogroms were coming to the United States; the number who immigrated to the U.S. between 1905 and 1906 alone exceeded 200,000.[38]

The immediate problem this posed for the Entente was that they needed weaponry, ammunition, horses, and other logistical support, along with loans for these purchases. Britain worked exclusively through the Anglophilic, New York-based J.P. Morgan and Company as their sole agent for arms purchases.[39] However, because a Jewish lobby that included a manager at American investment bank Kuhn, Loeb & Company was so outraged by the Tsar’s anti-Semitism, Russia was unable to raise any loans in New York.[40] Herbert Samuel’s argument that British support for a Jewish homeland would foster goodwill among the world’s Jewry, particularly in the United States, began to gain traction among British officials, as it “played upon the widespread prejudice that Jews were an increasingly powerful political force.”[41] French diplomats, when they learned of British support for Zionism, found it simply laughable, assuming that “no one would be so stupid as to pursue a policy that was bound to cause trouble between the Arabs and the Jews.”[42]

Special Christmas video courtesy of Sir Paul McCartney

[1] Ram Chandra, “India’s Voice at Last: India’s Reply to British Propagandists and Christian Missionaries, Rev. James L. Gordon, D.D., Especially (1912?), quoted in Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance & Indian Anticolonialism in North America (Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2014), at 17 and n.8. According to Sohi, this was a typical assertion in every issue of Ghadar, the weekly newspaper published by the Ghadar Party in San Francisco.

[2] Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance & Indian Anticolonialism in North America (Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2014), at 17.

[3] Text of the 1911 Act, which amended the version initially enacted in 1907, is at https://indiankanoon.org/doc/1211616/ (last viewed November 18, 2024). Another version is available at https://www.indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/15420/1/seditious_meeting_act_%282%29.pdf (last viewed November 18, 2024).

[4] Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance & Indian Anticolonialism in North America (Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2014), at 49.

[5] Tiffany Camhi, “A Racist History Shows Why Oregon is Still So White,” Oregon Public Broadcasting, June 9, 2020, available at https://www.opb.org/news/article/oregon-white-history-racist-foundations-black-exclusion-laws/ (last viewed November 18, 2024).

[6] Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance & Indian Anticolonialism in North America (Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2014), at 25.

[7] Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance & Indian Anticolonialism in North America (Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2014), at 108.

[8] The spy was William C. Hopkinson, who had grown up in northern India and previously served as the inspector of police in Calcutta. He was fluent in Hindi and Punjabi and was hired by the Canadian government in January 1909 in response to the rise of Indian resistance to discriminatory immigration policies in Canada. “According to rumors, he had a family and home in Vancouver but by day wore a turban and fake beard and posed as a laborer from Lahore named Narain Singh.” Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance & Indian Anticolonialism in North America (Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2014), at 40.

[9] Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance & Indian Anticolonialism in North America (Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2014), at 89.

[10] Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance & Indian Anticolonialism in North America (Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2014), at 45-46.

[11] Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance & Indian Anticolonialism in North America (Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2014), at 58.

[12] M. Hakan Yavuz, “Warfare and Nationalism: The Balkan Wars as a Catalyst for Homogenization,” in Yavuz, M.H. and Blumi, I., eds., War and Nationalism: The Balkan Wars, 1912-1913, and their sociopolitical Implicaitons (University of Utah Press: 2013), at 38-40. Several firsthand witnesses described Greeks as having “seized infants from their mothers’ breasts and dashed them against the rocks,” where two thousand others were “led out to a ravine in the neighboring mountains and there butchered like cattle.” Some estimates placed the number of Turks killed at approximately 20,000. Id. at 39.

[13] M. Hakan Yavuz, ‘Warfare and Nationalism,” at 43.

[14] Gül Tokay, “The Origins of the Balkan Wars: A Reinterpretation,” in Yavuz, M.H. and Blumi, I., eds., War and Nationalism: The Balkan Wars, 1912-1913, and their sociopolitical Implicaitons (University of Utah Press: 2013), at 176.

[15] M. Hakan Yavuz, ‘Warfare and Nationalism,” at 49.

[16] Gül Tokay, “The Origins of the Balkan Wars: A Reinterpretation,” at 180, 187.

[17] M. Hakan Yavuz, ‘Warfare and Nationalism,” at 51. In particular, the powerful Muntasir clan had been partisans of Ottoman Sultan ‘Abd al-Hamid II; when he was then overthrown by the Young Turks, the Muntasirs lost their position within the state bureaucracy. More than half of Libya’s 20,000 Jews lived in Tripoli and, as a small minority, they felt they could be better protected by allying themselves with the Italian conquerors. Many of them wanted to work in companies of the Bank of Rome or attend Italian schools. “Poor Jews were less enthusiastic than rich merchants; however, it seems that most Jews welcomed the Italians.” Ali Abdullatif Ahmida, The Making of Modern Libya: State Formation, Colonization, and Resistance, 1830-1932 (State University of New York Press: Albany, NY, 1994), at 108-11.

[18] Eyal Ginio, “Making Sense of the Defeat in the Balkan Wars: Voices from the Arab Provinces,” in Yavuz, M.H. and Blumi, I., eds., War and Nationalism: The Balkan Wars, 1912-1913, and their sociopolitical Implications (University of Utah Press: 2013), at 605-06.

[19] James Barr, A Line in the Sand: Britain, France, and the Struggle for the Mastery of the Middle East (2011), at 9.

[20] Gönül GÜNEŞ*, TEŞKİLAT-I MAHSUSA VE BİRİNCİ DÜNYA SAVAŞI YILLARINDAKİ FAALİYETLERİ, Hacettepe Üniversitesi Atatürk İlkeleri ve İnkılap Tarihi Enstitüsü. 4 Mart 2013. available at http://www.atam.gov.tr/wp-content/uploads/04-G%C3%B6n%C3%BCl-G%C3%BCnes.pdf

[21] Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance & Indian Anticolonialism in North America (Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2014), at 153.

[22] Heike Liebau, “’Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen’: Das Berliner Indische Unabhängig-keitskomitee in den Akten des Politischen Archivs des Auswärtigen Amts (1914 - 1920),” in: Archival Reflexicon, Anandita Bajpai and Heike Liebau (eds.), 2019, pp.1-10, at 1, available at https://perspectivia.net/servlets/MCRFileNodeServlet/pnet_derivate_00005699/liebau_aufwiegelungen.pdf (last viewed December 13, 2024).

[23] Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance & Indian Anticolonialism in North America (Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2014), at 165-66.

[24] Quoted in Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance & Indian Anticolonialism in North America (Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2014), at 166.

[25] Heike Liebau, “’Unternehmungen und Aufwiegelungen’: Das Berliner Indische Unabhängig-keitskomitee in den Akten des Politischen Archivs des Auswärtigen Amts (1914 - 1920),” in: Archival Reflexicon, Anandita Bajpai and Heike Liebau (eds.), 2019, pp.1-10, at 3.

[26] Hew Strachan, The First World War, Vol. I: To Arms (Oxford University Press, 2001), 658.

[27] C. Ernest Dawn, “The Origins of Arab Nationalism,” in Rashid Khalidi et al, eds, The Origins of Arab Nationalism (Columbia University Press: New York, Oxford, 1991), at 8-9.

[28] James Barr, A Line in the Sand: Britain, France, and the Struggle for the Mastery of the Middle East (2011), 17-18.

[29] Ahmed Tarabin, “’Abd al-Hamid al-Zahwari: The Career and Thought of an Arab Nationalist,” in in Rashid Khalidi et al, eds, The Origins of Arab Nationalism (Columbia University Press: New York, Oxford, 1991), at 102-03.

[30] James Barr, A Line in the Sand: Britain, France, and the Struggle for the Mastery of the Middle East (2011), at 9, 11, 16, 17.

[31] James Barr, A Line in the Sand: Britain, France, and the Struggle for the Mastery of the Middle East (2011), 16.

[32] Hew Strachan, The First World War, Vol. I: To Arms (Oxford University Press, 2001), 737.

[33] James Barr, A Line in the Sand: Britain, France, and the Struggle for the Mastery of the Middle East (2011), 13.

[34] James Barr, A Line in the Sand: Britain, France, and the Struggle for the Mastery of the Middle East (2011), 21-26.

[35] Edwin Black, IBM and the Holocaust (Random House: New York, New York, 2001), at 28.

[36] Nathan of Gaza, a Letter to Raphael Joseph, in Tsitsat Novel Tsevi, ed. Isaiah Tishby (Jerusalem: Mosad Byalik, 1954), 7–12, available at http://noahbickart.fastmail.fm.user.fm/TRS%20312/Nathan_of_Gaza_Letter.pdf (last viewed November 29, 2024). Nathan of Gaza actively promoted the idea that Shabbetai Levi, a Turkish Jew, was in fact the Messiah who would soon liberate Palestine from Turkish rule. Shabbetai Levi unfortunately was a scam artist who, when threatened by the sultan with death, promptly converted to Islam and took the name Mehemet Effendi. Nonetheless, Nathan’s letter “was greeted with particular enthusiasm coming as it did on the heels of the horrendous Chmielnitzki pogroms [of 1648-49, in what is now Ukraine] during which more than one hundred thousand Jews had been murdered…” Rabbi Joseph Telushkin, Jewish Literacy (William Morrow and Company: New York, NY, 2001), at 219.

[37] Telushkin, Jewish Literacy, at 282.

[38] Telushkin, Jewish Literacy, at 260.

[39] Hew Strachan, The First World War, Vol. I: To Arms (Oxford University Press, 2001), 963.

[40] However, “the barriers to American money did not constitute barriers to American goods,” and the major source of Russian munitions during the war was the United States. Hew Strachan, The First World War, Vol. I: To Arms (Oxford University Press, 2001), 956-57.

[41] James Barr, A Line in the Sand: Britain, France, and the Struggle for the Mastery of the Middle East (2011), 27.

[42] James Barr, A Line in the Sand: Britain, France, and the Struggle for the Mastery of the Middle East (2011), 30.

Wow. This is history that I missed along the way.