To recap (for folks joining late): This book/article’s working title is People, Places and Races: From the Peace of Westphalia to the NSA (via the Philippines). I’ve been posting it in sections weekly on Sundays. Thus far I have posted:

Intro:

Part I.A: I set the stage for my central proposition, which is that baked into U.S. law and policy from its inception is an Erroneous Assumption that our civilization has been able to conquer, colonize and enslave other people because of some deficiency in those people as individuals, rather than accidents of geography.

Part I.B. I unpack the myth surrounding the 1648 Peace of Westphalia, which is that it guaranteed the territorial integrity of nation-states, another idea that was imported into U.S. law as it acquired new territory. In reality, the Peace of Westphalia was about colonialism and conquest of the New World.

Part I.C. I explain the history of Western nations asserting jurisdiction extraterritorially over their own nationals in supposedly “barbaric” countries whose legal systems could not be trusted, including the Ottoman Empire, China and Japan.

And now we move on to Part Two:

II. The U.S. occupation of the Philippines and the birth of the U.S. national security state

A. The Pre-1898 U.S. National Security State

Jared Diamond’s scientific explanation of human progress ends around the year 1500 and does not further explain whether there is a natural progression among all human societies from states to information states to surveillance states of various types. There are some indications that such a progression might exist, albeit with substantial variations.[1] If one examines the modern U.S. national security state as a reference, the basic elements appear to include, on the one hand, an intelligence apparatus, which collects and produces information to guide decision-making,[2] and on the other, a decision-making entity able to operationalize the intelligence to protect the national or homeland security of the state, including but not limited to through physical force (typically executed either by military or law enforcement entities).[3]

The modern U.S. intelligence community recognizes six major sources of intelligence collection:

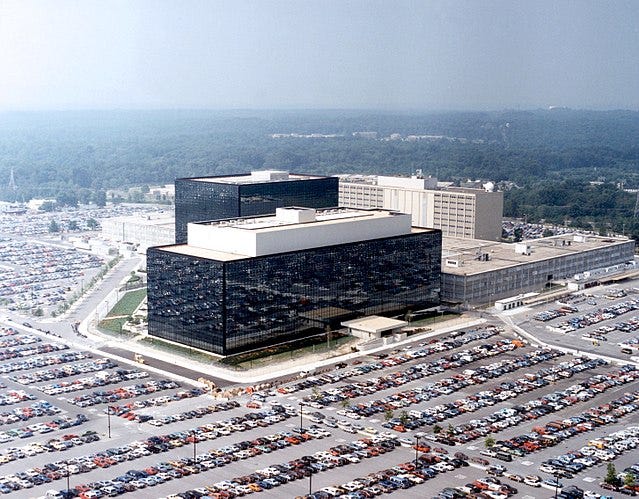

(1) Signals intelligence (SIGINT): intercepting and deciphering (through cryptanalysis) the content of communications (which today is the province of the NSA);

(2) Imagery intelligence (IMINT): representation of objects, such as through photography;

(3) Measurement and signal intelligence (MASINT): analysis of physical attributes of targets;

(4) Human intelligence (HUMINT): intelligence derived from human sources, whether through overt or clandestine means;

(5) Open source intelligence (OSINT): collection of publicly available data such as from newspapers, public records, the Internet, etc.; and

(6) Geospatial intelligence (GEOINT): the analysis and visual representation of security related activities on the earth.[4]

Unevaluated intelligence obtained through one or more of the above collection methods is referred to within the U.S. intelligence community as “raw” intelligence. Raw intelligence may be passed directly to decision-makers, but it can also serve as original source material for analytic intelligence products for those same decision-makers.[5]

Another important source of intelligence is simply identity resolution, i.e., the ability to identify an individual to the exclusion of other individuals, which today is used in a wide variety of screening and vetting contexts such as passport and visa issuance and transportation security. Indeed, “[i]f one were asked to create a list of the features of the modern Western state which sets it apart from previous political formations, the central collection and analysis of information, especially that on individuals, would be a strong contender for inclusion.”[6] This can occur through simple collection and collation of personally identifiable information such as names and birth dates (for societies that record such information reliably and in a manner sufficient to differentiate one person from another), or through more technologically sophisticated means such as biometric technology (fingerprints, photographs, gait analysis, DNA etc.).

As of 2024, the U.S. intelligence budget appropriation for fiscal year 2023 (including both the national intelligence program and the military intelligence program) was $99.6 billion.[7] On the decision-making and enforcement side, in 2024, the U.S. has an estimated national security budget of $1.25 trillion, much of it consumed by both the Defense Department’s “base budget” and its Overseas Contingency Operations budget, which “in theory…is meant to pay for the war on terror.”[8] As of 2020, the U.S. federal government employed 136,815 full-time federal law enforcement officers spread across ninety agencies.[9] This is in addition to the many state, local, tribal and territorial (SLTT) law enforcement officers who are not employed by the U.S. federal government but who do consume and act upon intelligence produced by the U.S. intelligence community. As of June 2018, there were 17,541 state and local agencies performing law enforcement functions in the United States, employing 1,214,000 full-time sworn and civilian personnel.[10]

The size and complexity of the modern U.S. national security state would be unimaginable and most likely appalling to the proponents of “limited government” who drafted and applied the Constitution in its early years. In fact, prior to the United States acquisition and conquest of the Philippines in the War of 1898, the United States was trailing behind Europe’s development of surveillance states in many respects, across several of the major collection disciplines and certainly enforcement capacity:

SIGINT (intercept of communications): In Europe, the “use of political cryptology…has continued uninterrupted to the present as it emerged from the feudalism of the Middle Ages.”[11] Its growth went hand in hand with modern European diplomacy (exemplified by the Westphalian nation-state system) that involved the stationing of ambassadors in each other’s territory; ambassadors sent home regular reports, which the host country keenly wished to spy upon. From 1542 onwards, the city-state of Venice had three cipher secretaries who intercepted and deciphered the diplomatic communications of other foreign powers.[12] By the 1700s it was common among European powers to maintain “black chambers” (cabinets noirs) of cryptanalysts to do so routinely.[13] Beyond diplomatic communications, many if not most European governments, including England, had long exercised their sovereign prerogative to open and read all sorts of personal mail, and later, telegrams.[14] Indeed, the advent of telegraphed diplomatic communications resolved one of the great problems of the cabinets noirs, how to lay hands on diplomatic mail, since governments could now simply access the telegrams through the telegraph offices in their main capitals.[15]

In the United States, by contrast, the Post Office Act of 1792 explicitly prohibited postal officers from opening letters, under criminal penalty.[16] The same Act set extremely favorable rates for delivery of newspapers through the mail, allowing the proliferation of the free press to such a degree that, when Alexis de Tocqueville toured the Appalachians in 1831, he observed an “astonishing circulation of letters and newspapers among these savage woods.”[17] By contrast, in his home country of France, the cabinet noir was so notorious that “during the War of Independence virtually every American diplomat [including several future Presidents] found occasion to complain.”[18] The U.S. Congress, prohibited by the First Amendment to the Constitution from enacting any law abridging the freedom of speech or of the press, produced no real reason for U.S. Government officials to surveil the contents of either newspapers or private correspondence. In 1835, a group of men broke into the post office in Charleston, South Carolina and destroyed several thousand abolitionist newspapers that had recently arrived from New York City, in violation of a South Carolina state law that prohibited publications whose transmission might incite a slave rebellion.[19] However, when anti-abolitionists then tried to convince the U.S. Congress to prohibit the transmission of abolitionist literature in the mail, they “met with a resounding defeat…Congress refused to take any concrete steps to restrict the freedom of the press.”[20]

Telegraph lines in the United States, of which there were already 50,000 miles installed by 1861, were primarily supported by private railroads, newspapers and financial markets, with little government involvement; Samuel Morse offered his patent to the U.S. Post Office but was told that “electronic messages would never replace the mail.”[21] In 1862, the U.S. Congress enacted legislation allowing the government to take control of the telegraph lines as necessary for military purposes,[22] and the conduct of the U.S. Civil War was in many instances deeply influenced by the use of telegraphed communications between military commanders and with President Lincoln in particular. Rebel forces sometimes cut Union telegraph lines,[23] but there is very little evidence that either side to the conflict actually tapped and deciphered enemy telegraphs.[24] After the war, the U.S. Government demonstrated neither an interest in intercepting telegrams nor even very much concern about the security of its own diplomatic communications. At the height of the diplomatic crisis that preceded the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898, the U.S. State Department was notified that “Madrid was in possession of the main U.S. diplomatic code, the ‘Red Code,’ introduced in 1876. American diplomacy appears to have been unaffected by this discovery. The U.S. minister to Spain carried on with his negotiations as before.”[25]

HUMINT (human intelligence): Here, the European powers also excelled relative to the United States, and arguably still do. For most of the 19th Century, the vast majority of European males were disenfranchised based on class distinctions,[26] with the ruling monarchs generally convinced that the main threat to their survival was a potential uprising. Their regimes therefore depended heavily upon secret police maintaining networks of informants within their restless populations. In France, such practices were pioneered by Joseph Fouché, who as Minister of Police from 1799 onwards built a vast network of agents who were partly financed by levies on brothels and gaming houses.[27] Following the unsuccessful 1848 uprisings across Europe calling for democracy, civil liberties, and universal male suffrage, the counter-revolutionary forces returned with a vengeance.[28] Many revolutionaries from continental Europe became political refugees in London afterwards, where secret police from their home countries followed them and sometimes demanded action from Britain’s Metropolitan Police (“the Met”). The Prussian Interior Minister Ferdinand von Westphalen, for example, sent legions of police spies and agents provocateurs to foreign capitals to keep tabs on émigré revolutionaries, particularly his brother-in-law Karl Marx.[29]

The British also made heavy use of human intelligence in India during its initial conquest and rule via the East India Company (EIC), effectively leveraging existing systems of internal espionage that had long supported the rule of the Mughals and other kingdoms.[30] British intelligence networks, however, failed entirely to predict the 1857 Sepoy Mutiny, which precipitated the replacement of the East India Company (EIC) with direct British rule,[31] and which then led to new intelligence collection techniques, such as the surveillance of the burgeoning Indian press. Policing in towns became more uniform by the 1860s, and “most district superintendents of police had effective systems of spies and informers which they used to contain urban robberies, grain riots and outbreaks of sectarian violence during festivals.”[32]

In the United States, by contrast, the intelligence-gathering capacity that had been created to wage the Civil War[33] had been gradually dismantled upon formal cessation of hostilities. Lincoln’s wartime spy chief, Army officer Lafayette Baker, assisted with the 12-day manhunt for Lincoln’s assassin and co-conspirators in April 1865.[34] He was then fired by President Andrew Johnson in 1867. After that, the only entity that remained collecting human intelligence was the U.S. Secret Service, initially created by Lincoln in 1865 and placed under the Treasury Department to combat counterfeit paper currency. Between 1871 and 1874, the Secret Service employed a total of eight undercover agents throughout the South to infiltrate and disable the entire Ku Klux Klan.[35] By 1874, even this minimal effort had been abandoned along with most of the other lofty goals of the Reconstruction era, and the Secret Service was largely relegated to its original mission, although agents could be loaned out to other federal agencies for miscellaneous detective and police work. This was the only option available to these other federal agencies, particularly after the U.S. Army was prohibited from investigating civilians in the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878.[36]

IMINT, MASINT, GEOINT: The necessary precursors to these disciplines were reconnaissance, cartography, and later, photography (especially aerial photography).[37] Naval navigation and reconnaissance were essential to early European colonization of the New World and later India, Africa, and East Asia.[38] The United States only became interested in global naval expansion in the late 19th century, due in part to the scholarship of naval historian and strategist Captain Alfred Thayer Mahan; a lecture he gave at the U.S. Naval War College in 1886 impressed recent Harvard graduate Theodore Roosevelt, who embraced Mahan’s expansionist thinking.[39]

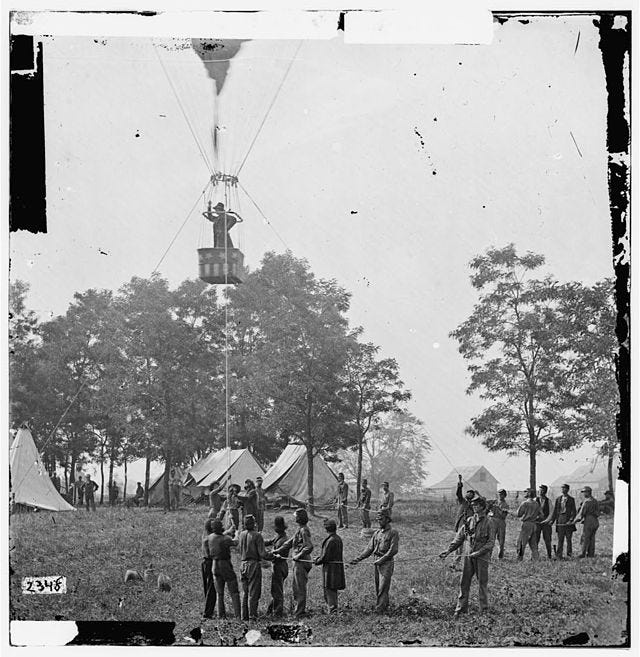

On land, the United States was the happy beneficiary of not only the English cartographic tradition, but significant contributions from Native Americans, who were quite adept at making maps to assist with massive cartographic undertakings such as the Lewis and Clark expedition of 1804-06.[40] By the time of the Civil War, the Union Army was already experimenting, somewhat unsuccessfully, with aerial battlefield reconnaissance via balloon.[41] However, following the Civil War, the only reconnaissance forces that remained were the U.S. Army cavalry scouts, who were deployed to the Western frontier.[42]

In 1891, the Army’s newly established Military Intelligence Division (MID), responding to a complaint about the absence “of any authentic maps of the country on our northern boundary, or of Mexico,” began preparing maps of those areas, and on Cuba the following year.[43] But as late as August 1897, amid rising tensions with Spain, the Army refused to allow MID to send an officer in disguise to map the harbors of Cuba before a formal declaration of war, because formal government policy considered such acts of espionage unethical in times of peace.[44]

In any event, the pre-20th-century United States appears never to have used its cartographic or aerial surveillance capabilities for large-scale civilian population control. This is in sharp contrast to the English, who over the course of a century co-opted indigenous mapping traditions in India and conducted their own land surveys to solidify imperial control and revenue generation there.[45]

OSINT: With the advent of the telegraph, journalists covering global conflicts such as the Crimean War of 1853-56 could report news back to their home countries within hours, greatly enhancing the utility of gathering open source military intelligence on one’s opponents simply by reading the newspaper.[46] During the U.S. Civil War, the Confederacy gathered intelligence by reading Northern newspapers; the Union was somewhat disadvantaged in this regard, since the South had fewer newspapers.[47] With the cessation of formal hostilities, however, there is no indication that any sort of peacetime governmental entity systematically read newspapers for their intelligence value. This is, again, in contrast to Europe, where

for the most part newspapers could only legally operate where licensed by the state, and where they were systematically reviewed by censors for purposes of enforcing strict and often vague censorship laws that resulted in thousands of journalists being fined or jailed; Napoleon I once candidly declared, “If I allowed a free press, I would not be in power for another three months.”[48]

The United States in the late 19th century made some minimal efforts to overtly gather information on foreign navies and military forces through overseas attaches, and perhaps more importantly, to organize this information in some sort of retrievable fashion. To that end, an Office of Naval Intelligence was established in 1882 and the War Department’s aforementioned Military Intelligence Division (MID) in 1886.[49] By 1898 the ONI consisted of five officers, four copyists, a clerk from the Bureau of Supplies and Accounts, an assistant draftsman from the Bureau of Construction and Repair, and one laborer from the Nautical Almanac Office.[50]. The MID consisted of eleven officers in addition to sixteen attaches scattered from Tokyo to London.[51]

Identity Resolution: The ability to identify an individual to the exclusion of other individuals can be accomplished through a variety of means, including tattoos, vital records management, census taking, personal identification numbers, and biometrics (photographs, fingerprinting, etc.). In order to utilize identity resolution to facilitate population control on a mass scale, the information collected also has to be readily retrievable by particular attributes. For much of the 19th century, most of the biometric technologies and technologies were not feasible for large-scale population tracking in either the United States or Europe. The taking of a national census, which was provided for in the U.S. Constitution and which first occurred in England in 1801, did not appear to facilitate the “overt social control of individuals”; in the case of England, the first census may have been an attempt to assess the size of the population able to bear arms in the Napoleonic Wars.[52] In 1837 England established the General Register Office (GRO) to administer a new system of civil registration of births, marriages and deaths.[53] At the same time English colonists in India began requiring village watchmen to report on births in the village, as “[e]numerating the people had become more important to the British partly because taxation was becoming a matter of individual means rather than community obligation.”[54] In the United States, the maintenance of vital records was and has remained at the state level, and Americans continue to strenuously resist the notion of a national ID.[55]

In the absence of more sophisticated technologies, English and American slaveowners identified slaves simply by branding them.[56] This practice was also utilized by Western colonial powers in Africa to maintain control of African forced laborers in the late 19th century.[57]

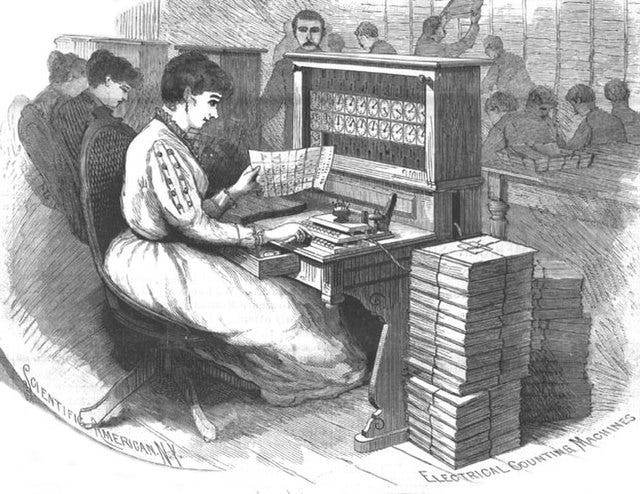

The United States did embrace one key innovation in the late 19th century that was to later have enormous implications for large-scale personal data processing. In 1879, the Director of Vital Statistics at the U.S. Census Bureau remarked over dinner to one of his young employees, “There ought to be a machine for doing the purely mechanical work of tabulating population and similar statistics.” The young employee, 19-year-old German-American immigrant Herman Hollerith, immediately began work on a machine that could tabulate results fed to it through paper cards with hole punches. By 1884 he had developed a prototype that then was used for the first time in the 1890 U.S. Census, where his system

saved the Census Bureau some $5 million, or about a third of its budget. Computations were completed with unprecedented speed and added a dramatic new dimension to the entire nature of census taking. Whereas in 1870 only five census topics were asked, amounting to little more than a head-count, many more personal questions were added. Indeed, now an army of census takers could posit 235 questions, including queries about the languages spoken in the household, the number of children living at home and elsewhere, the level of each family member’s schooling, country of origin, religious affiliation, and scores of other traits. Suddenly, the government could profile its own population.[58]

Enforcement capacity: Here, the real differences between the United States and Europe are more readily evident. Law enforcement capacity in the United States has always resided overwhelmingly at the state and local level,[59] with large businesses in the late 19th century often augmenting their security with private entities such as the Pinkerton Detective Agency.[60] Because the U.S. Supreme Court did not apply Fourth Amendment limitations on search and seizure to state and local law enforcement activity until 1961,[61] it is difficult to assess the overall impact of sub-federal law enforcement on the privacy and civil liberties of Americans, other than to note that its impact on labor activists[62] and African-Americans in the post-Civil War and pre-civil rights era in the South was considerable.[63] At the federal level, however, it is undeniable that the U.S. Government eschewed the notion of either substantial federal police forces or a large standing army in deliberate and marked contrast to Europe.

The Federal Judiciary Act of 1789 provided for the appointment of what initially amounted to 13 federal Marshals "to execute throughout the District, all lawful precepts directed to [them], and issued under the authority of the United States."[64] Until the mid-20th century, U.S. Marshals hired their own Deputies, “often firing the Deputies who had worked for the previous Marshal,” and sometimes deputized state and local police to carry out searches as part of their central function, which was simply to support the federal courts.[65] The only other federal law enforcement agency in existence was the U.S. Secret Service, whose primary mission after the Reconstruction era was combatting money laundering. In 1894, the Secret Service uncovered an assassination plot against President Grover Cleveland while investigating a gambling ring and was subsequently pressured by Cleveland’s wife to post a couple of agents at the family’s summer residence, which then caused a political uproar.[66] Despite two presidents in recent memory, Lincoln and Garfield, having been politically assassinated in office, public and Congressional opposition to any kind of protective detail for the President of the United States would continue unabated until 1906, when the Secret Service was finally authorized the mission by statute, five years after President McKinley had also been assassinated.[67]

As for the U.S. Army, one of the many reasons cited in 1848 for not annexing more of Mexico or even extending the U.S. military occupation following the Mexican-American War was that it would require the employment of soldiers “for the purpose of gathering treasures, and keeping in awe a feeble and distracted population.” [68] It was fine to recruit soldiers on a temporary basis who would be primarily “animated by the love of glory and the spirit of military adventure,” but the use of a standing army to suppress a civilian population was a European practice that U.S. policymakers were pointedly rejecting. By contrast, many of the technological developments that increased infantry firepower 60-fold between 1840 and 1870, were used by European regimes to deploy their armies directly against their own civilian populations, where they could now

easily put down all but the most serious of disorders. A high level of spending on military and police forces was characteristic of most European regimes in the post-1848 period, reflecting both fears of lower-class upheavals and heightened international tensions…Around 1870, Italy and Prussia both spent about ten times as much on the military as on education; Austria spent twice as much on the police alone as on the school system.[69]

After an 1873 uprising in Spain, “[t]he federalist or ‘cantonalist’ revolts forced the government to suspend civil liberties and rely heavily upon the conservative army leadership, which suppressed the revolts quickly…About 15,000 Spaniards were arrested and 1,400 were deported to the Philippines.”[70]

European regimes also needed large armies to occupy their overseas colonies. The British had needed 20,000 troops simply to wage the Opium Wars against China in the 1830s, in addition to its three dozen warships.[71] By 1846 the French had more than 100,000 soldiers stationed in North Africa.[72] The need for occupying armies only increased after various approaches to “informal” empires in the early 19th century had proven inadequate, and the Europeans began furiously competing with one another to snatch up territory in Africa and Southeast Asia.[73]

On the eve of war with Spain in 1898, the entire U.S. Army numbered only about 28,000 men assigned in small detachments across the country.[74] By comparison, the Spanish Army in 1898 contained a total of 492,067 men: 289,000 in the Caribbean; 51,000 in the Philippines; and 152,000 in Spain.[75]

[1] The use of spies, for example, is promoted in the Indian manual of statecraft the Arthashastra, reputed to have been written by Chandragupta Maurya (317-293 B.C.).

The Arthashastra was the first book anywhere in the world to call for the establishment of a professional intelligence service. It discussed in enormous detail, not since surpassed in any unclassified manual of statecraft, the recruitment, uses and twenty-nine main cover occupations (with fifty sub-types) of a huge network of spies at home and abroad. The network was such a high priority that the King was told to take personal charge of it.

Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2018), at 61. See also C.A. Bayly, Empire & Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communication in India, 1780-1870 (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1996), at 13 (“Political surveillance has been vital for all large historical states…”). Even prior to the British conquest of India, “later Mughal government and the successor states of the eighteenth century were in some respects becoming more bureaucratic, more reliant on the use of paper and the archive, and more dependent on systems of political surveillance.” Id. at 367. With regard to cryptology, or the dual field of both rendering signals secure (cryptography) and extracting information from them (cryptanalysis), see also David Kahn, The Code Breakers (The MacMillan Company, 1972), at 84:

It must be that as soon as a culture has reached a certain level, probably measured largely by its literacy, cryptography appears spontaneously—as its parents, language and writing, probably also did. The multiple human needs and desires that demand privacy among two or more people in the midst of social life must inevitably lead to cryptology wherever men thrive and wherever they write.

As political scientist Jennifer Luff points out, a uniquely American twist on the “surveillance state” is the phenomenon of “popular political policing via congressional committee,” which mixes “antiradicalism with antistatism” and conducts its repression out in the open, as an expression of popular will (which she describes as “a C-SPAN problem”). Luff makes a solid argument that the U.S. tendency to “fight our battles in the sunshine” is not necessarily less repressive than political policing conducted secretly by an executive. Nonetheless, this section examines primarily the evolution of intelligence gathering within executive branch rather than legislative bodies. Jennifer Luff, “Covert and Overt Operations: Interwar Political Policing in the United States and the United Kingdom,” American Historical Review, vol. 122, no. 3 (June 2017), 727-57.

[2] The U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence (ODNI) defines intelligence as

information gathered within or outside the U.S. that involves threats to our nation, its people, property, or interests; development, proliferation, or use of weapons of mass destruction; and any other matter bearing on the U.S. national or homeland security. Intelligence can provide insights not available elsewhere that warn of potential threats and opportunities, assess probable outcomes of proposed policy options, provide leadership profiles on foreign officials, and inform official travelers of counterintelligence and security threats.

ODNI, “What is Intelligence?” at https://www.odni.gov/index.php/what-we-do/what-is-intelligence (viewed September 18, 2024).

[3] See generally Erik Dahl, Intelligence and Surprise Attack: Failure and Success from Pearl Harbor to 9/11 and Beyond (Georgetown University Press, 2013).

[4] ODNI, “What is Intelligence?”, supra.

[5] Within the U.S. intelligence community, intelligence analysts have different tradecraft standards than intelligence collectors and are a somewhat separate profession. See Intelligence Community Directive 203 Analytic Standards, December 21, 2022, available at https://www.odni.gov/files/documents/ICD/ICD-203_TA_Analytic_Standards_21_Dec_2022.pdf (viewed September 18, 2024).

[6] Edward Higgs, “The Rise of the Information State: The Development of Central State Surveillance of the Citizen in England, 1500-2000,” Journal of Historical Sociology, Vol. 14 No. 2 June 2001, at 175.

[7] U.S. Intelligence Community Budget, available at https://www.dni.gov/index.php/what-we-do/ic-budget.

[8] https://www.pogo.org/analysis/making-sense-of-the-1-25-trillion-national-security-state-budget.

[9] U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, Federal Law Enforcement Officers, 2020—Statistical Tables, September 2022, Revised September 29, 2023, available at https://bjs.ojp.gov/document/fleo20st.pdf.

[10] Andrea M. Gardner and Kevin M. Scott, Census of State and Local Law Enforcement Agencies, 2018—Statistical Tables, U.S. Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics, available at https://bjs.ojp.gov/library/publications/census-state-and-local-law-enforcement-agencies-2018-statistical-tables (viewed September 18, 2024).

[11] David Kahn, The Code Breakers (The MacMillan Company, 1972), at 106.

[12] Kahn, at 109.

[13] The black chamber or Geheime Kabinets-Kanzlei at Vienna was reputed to be the best in Europe.

It ran with almost unbelievable efficiency. The bags of mail for delivery that morning to the embassies in Vienna were brought to the black chamber each day at 7 a.m. There the letters were opened by melting their seals with a candle. The order of the letters in an envelope was noted and the letters given to a subdirectory. He read them and ordered the important parts copied…Two translators were always on hand. All European languages could be read, and when a new one was needed, an official learned it…At 10 a.m., the mail that was passing through this crossroads of the continent arrived and was handled in the same way…Usually it would be back in the post by 2 p.m., though sometimes it was kept as late as 7 p.m. At 11 a.m., interceptions made by the police for purposes of political surveillance arrived. And at 4 p.m., the couriers brought the letters that the embassies were sending out that day. These were back into the stream of communications by 6:30 p.m. Copied material was handed to the director of the cabinet, who excerpted information of special interest and routed it to the proper agencies, as police, army, or railway administration, and sent the mass of diplomatic material to the court. All told, the ten-man cabinet handled an average of between 80 and 100 letters a day.

Kahn, at 163-64.

[14] “Between 1798 and 1844, British judges issued no fewer than 372 separate search warrants authorizing the opening of letters; at one point, they went so far as to empower surveyors to travel through the north of a country with a general warrant to open the letters of virtually anyone they pleased.” Richard R. John, Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse (First Harvard University Press, 1998), at 43. See also Report of the Committee of Privy Councillors appointed to inquire into the interception of communications, presented to Parliament by the Prime Minister by Command of Her Majesty October 1957, available at https://www.fipr.org/rip/Birkett.htm (viewed September 21, 2024). The uproar over the 1844 Mazzini incident led to the closure of the British Deciphering Branch that same year; however, cryptography remained a central feature among “black chambers” across the European Continent and was eventually taken back up by the British as well during World War I.

[15] Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press, 2018), at 421.

[16] An Act to Establish the Post-Office and Post Roads within the United States, Feb. 20, 1792, 2nd Cong., Sess. 1, Ch. 7, Section 16.

[17] Alexis de Tocqueville, Journey to America, quoted in Richard R. John, Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse (First Harvard University Press, 1998), at 1.

[18] Richard R. John, Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse (First Harvard University Press, 1998), at 44.

[19] Richard R. John, Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse (First Harvard University Press, 1998), at 257-280.

[20] Richard R. John, Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse (First Harvard University Press, 1998), at 273.

[21] Tom Wheeler, Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails: How Abraham Lincoln Used the Telegraph to Win the Civil War (Harper Collins: New York, NY, 2006), at xvi-xvii.

[22] Wheeler, Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails, 9.

[23] Wheeler, Mr. Lincoln’s T-Mails, 4.

[24] Edwin C. Fishel, The Secret War for the Union: The Untold Story of Military Intelligence in the Civil War (Houghton Mifflin Co., 1996), at 4-5.

[25] Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press, 2018), at 424.

[26] As late as 1880, class-based restrictions on suffrage excluded more than 90 percent of the population from voting (or 60 percent of adult males) in Austria, Belgium, Finland, Hungary, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Russia, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. “Further, in most countries with a more liberal suffrage system in 1880, elections were either systematically rigged (e.g., Bulgaria, Portugal, Rumania, Serbia) or the lack of a parliamentary responsibility greatly reduced the significance of a broad franchise (e.g., Denmark, Germany).” Robert Justin Goldstein, Political Repression in 19th Century Europe (Croom Helm Lt. Kent, 1983), at 334. Typically the poor were excluded from voting by making it dependent upon “a minimum amount of income, a minimum amount of property, and/or the payment of a minimum amount of direct tax based on property and/or income.” Id. at 8. “Until about 1880, civil liberties were either nonexistent or extremely tenuous in France.” Id. at 270.

[27] Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2018), at 341-2. Napoleon, who was somewhat terrified of Fouché, tried to dismiss him from office in 1802 but reinstated him two years later. Richard Deacon, The French Secret Service (Grafton Books: London, 1990), at 49-50.

[28] According to Goldstein, “the majority of the revolutionary outbreaks in Europe during the 1815-1914 period focused upon civil liberties demands,” and “[t]he sudden explosion of political clubs and meetings throughout Europe in 1848 and their rapid disappearance in the post-1848 reaction offers additional evidence as to the effectiveness of nineteenth-century political repression. Goldstein, Political Repression in 19th Century Europe, at 338. He adds, “[u]ntil about 1880, civil liberties were either nonexistent or extremely tenuous in France.” Id. at 270.

[29] Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2018), at 388-89.

[30] In Indian kingdoms dating back millenia, “royal intelligence was heavily dependent on informal networks of knowledgeable people.” C.A. Bayly, Empire & Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communication in India, 1780-1870 (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1996), at 10. “What Muslim rulers, particularly the Mughals, gradually introduced after 1200 AD was a more regular system of official political reporting and a comprehensive grid of regular post stages (dak chaukis) under recognized officials.” Id. at 14. Official news was “supplemented with reports from a range of secret agents (swanih nigars or khufia naviss) who moved around the countryside, listening in at bazaars and checking on the reports of the provincial governors and the official newswriters.” Id. at 15. “One overriding reason why the East India Company was able to conquer India and dominate it for more than a century was that the British had learnt the art of listening in, as it were, on the internal communications of Indian polity and society.” Id. at 365.

[31] Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press: New Haven and London, 2018), at 410.

[32] C.A. Bayly, Empire & Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communication in India, 1780-1870 (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1996), at 339.

[33] The use of military intelligence by Union forces is covered exhaustively in Edwin C. Fishel, The Secret War for the Union: The Untold Story of Military Intelligence in the Civil War (Houghton Mifflin Co., 1996). The use of ciphers by Union and Confederate forces in letters and telegrams is discussed in David Kahn, the Codebreakers (MacMilaln Company, New York, NY, 1967), in Chapter 7.

[34] “Lafayette Baker, the Scoundrel Spy Chief,” at https://www.intelligence.gov/evolution-of-espionage/civil-war/union-espionage/lafayette-baker (viewed May 6, 2024).

[35] See Charles Lane, Freedom’s Detective: The Secret Service, the Ku Klux Klan, and the Man Who Masterminded America’s First War on Terror (Hanover Square Press, 2019).

[36] 18 U.S.C. § 1385, quoted and discussed in “The Posse Comitatus Act and Using Military as a Police Force,” Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library and Museum website at https://www.rbhayes.org/scholarlyworks/the-posse-comitatus-act-and-using-military-as-a-police-force/ (viewed May 6, 2024).

[37] Reconnaissance is as old as the Bible: “And Moses sent them to spy out the land of Canaan, and said until them, ‘Get you up this [way] southward, and go up into the mountain: And see the land, what it [is]; and the people that dwelleth therein, whether they [be] strong or weak, few or many…” Numbers 13: 1-20, quoted in Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press, 2018), at 13. Cartography, or the art and science of mapping geographical spaces, originated in the West with ancient Greek mathematicians and scientists such as Erastosthenes (who was able to calculate the circumference of the Earth) and Ptolemy, author of the Geography. See Editors, “The Growth of an Empirical Cartography in Hellenistic Greece,” and O.A.W. Dilke, “The Culmination of Greek Cartography in Ptolemy,” in J.B. Harley and David Woodward, eds., The History of Cartography (University of Chicago Press, 1987), Volume 1, available at https://press.uchicago.edu/books/hoc/index.html (viewed September 30, 2024). While much of Ptolemy’s knowledge of mathematics was lost to Europe during Europe’s Dark Ages, it was translated into Arabic in the 7th Century, becoming part of the Islamic cartographic tradition, and then re-introduced into Europe during the Renaissance. See Ahmet T. Karamustafa, “Introduction to Islamic Maps,” in The History of Cartography, Vol. 2 Book 1, at 4; Patrick Gautier Dalché, “The Reception of Ptolemy’s Geography (End of the Fourteenth to the Beginning of the Sixteenth Century,” in The History of Cartography, Vol. 3 (Part 1).

[38] See generally Felipe Fernández-Armesto, “Maps and Exploration in the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries,” and Eric Ash, “Navigation Techniques and Practice in the Renaissance,” in The History of Cartography, Vol. 3 Part 1. China once had enormous technological advantages over Europe. Between 1405 and 1433, China sent out seven “treasure fleets” that reached the east coast of Africa, but following a power struggle between two factions at the Chinese court, the fleets were destroyed and trans-oceanic shipping forbidden, allowing formerly “backwards” European maritime explorers to take the lead. Diamond, Guns, Germs and Steel, at 411-13.

[39] Ivan Musicant, Empire by Default: The Spanish-American War and the Dawn of the American Century (Henry Holt and Company: New York, 1998), at 5-9.

[40] See G. Malcolm Lewis, “Maps, Mapmaking, and Map Use by Native North Americans,” in J.B. Harley and David Woodward, eds., The History of Cartography (University of Chicago Press, 1987), Volume II Book 3, available at https://press.uchicago.edu/books/hoc/index.html (viewed September 30, 2024), at 114. Several early Spanish, French and English explorers had encounters with Native Americans in which the latter demonstrated their ability to map land with great precision. A Jesuit missionary who observed northern Iroquoian Indians between 1712 and 1717 observed that they had

an excellent sense (of direction)…They go straight where they wish to go, even in uncharted wildernesses and where no paths are marked. On their return, they have observed everything and trace, grossly, on sheets of bark or on the sand, exact maps on which only the marking of degrees is lacking. They even keep some of these geographical maps in their public treasury to consult them at need.

Quoted in id. at 81. Native Americans used maps regularly in planning, gathering information and instruction, “usually connected with war or travel beyond normal territorial limits.” Id. at 180.

[41] Edwin C. Fishel, The Secret War for the Union (Houghton Mifflin Company: Boston and New York, 1996), 5. Balloon surveillance was discontinued by the U.S. Army after 1863; “although [the balloons’] advantage in altitude yielded observations the signal stations could not make, that may not have been enough to compensate for their logistical troubles.” Id. at 443. The French photographer and balloonist known as Nadar believed in the potential of aerial photography for military espionage, but he appears to have experienced similar frustrations with regard to the inability to direct a balloon’s flight. Philip McCouat, “The Adventures of Nadar,” Journal of Art and Society, available at https://www.artinsociety.com/the-adventures-of-nadar-photography-ballooning-invention--the-impressionists.html (viewed October 1, 2024).

[42] Patrick Eugene McGinty, M.A., Intelligence and the Spanish American War, a dissertation submitted to the faculty of the graduate school of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, Washington, D.C., September 1981, Thesis 5409, p. 37-38.

[43] McGinty, at 41-2.

[44] McGinty, at 135.

[45] See C.A. Bayly, Empire & Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communication in India, 1780-1870 (Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 1996), at 300-09.

[46] In Britain, “[f]or the first time ministers were likely to see reports of wars and major events in freshly ironed copies of The Times brought to them by their butlers at home before they read official despatches from British commanders and diplmats in their Whitehall offices…The British commander-in-chief, Lord Raglan…complained that, thanks to The Times, the Russians had little need for spies and ‘need spend nothing under the head of “Secret Service.”’”). Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press, 2018), at 402.

[47] ADD CITATION.

[48] Robert Justin Goldstein, Political Repression in 19th Century Europe (Croom Helm Lt. Kent, 1983), at 34, 42.

[49] Patrick Eugene McGinty, M.A., Intelligence and the Spanish American War, p. 29-32. The purpose of ONI was “to be a depository and central management office for various reports on the strengths and weaknesses of several foreign navies.” Id. at 31-32. McGinty notes, “the era between 1865 and 1882 marked a nadir for the Navy in terms not only of equipment, morale, and operational effectiveness, but also intelligence collection and production…[T]his period was followed by a period of reformist zeal in naval circles and naval intelligence, as well as other aspects of the navy in general, benefited by the reform and rebuilding programs which occurred during the second time frame, 1882 to 1898.” Id. at 36. Eventually the War Department founded a small office in 1885 to serve as the general equivalent of the ONI created in 1882. This office came to be known around 1886 as the Military Information Division. Id. at 39-40.

[50] Packard, 7-8.

[51] McGinty, 44.

[52] Edward Higgs, “The Rise of the Information State: The Development of Central State Surveillance of the Citizen in England, 1500-2000,” Journal of Historical Sociology, Vol. 14 No. 2 June 2001, at 179.

[53] Edward Higgs, “The Rise of the Information State: The Development of Central State Surveillance of the Citizen in England, 1500-2000,” Journal of Historical Sociology, Vol. 14 No. 2 June 2001, at 180.

[54] C.A. Bayly, Empire & Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communication in India, 1780-1870 (Cambridge University Press, 1996) at 372.

[55] See, e.g., Jim Harper, “The REAL ID deadline will never arrive,” The Atlantic, May 14, 2024, available at https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2024/05/real-id-deadline-will-never-arrive/678370/ (viewed October 3, 2024); Rebecca Reyes, “The Unconstitutioality of REAL ID and Its Effects on Undocumented Immigrants in the U.S.,” Columbia Undergraduate Law Review, January 19, 2022, available at https://www.culawreview.org/journal/the-unconstitutionality-of-real-id-legislation-and-its-effects-on-undocumented-immigrants-in-the-us (viewed October 3, 2024).

[56] Lani L. Biafore, “American Slave Branding: Insidious Identification and Depraved Punishment,” Criminal Law Journal (California Lawyers Association), No. 20-1, September 2020, available at https://law-journals-books.vlex.com/vid/american-slave-branding-insidious-935405551 (viewed October 1, 2024); Karla Adam, “A crown branded onto bodies links British monarchy to slave trade,” Washington Post, Sep. 28, 2023, available at https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2023/09/28/slave-trade-monarchy-uk-archives/ (viewed October 1, 2024).

[57] See, e.g., Michael Kwet, “Surveillance in South Africa: From Skin Branding to Colonialism,” Draft 1.0, The Cambridge Handbook of Race and Surveillance, September 2020, at 2-3: “In the absence of advanced technology, whites resorted to barbarous techniques…settlers resorted to ‘writing on the skin’ of Africans and livestock. Using hot irons, needles and Indian ink, they branded bodies with unique symbols also listed in paper registers.” Available at https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3677168#:~:text=However%2C%20today%20a%20regime%20of,%2C%20and%20profit%2Dseeking%20capitalists (viewed July 23, 2024).

[58] Edwin Black, IBM and the Holocaust (Random House: New York, New York, 2001), at 26. Hollerith eventually sold his Tabulating Machine Company to an entity called the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company, or CTR, headed by Thomas J. Watson. Id. at 31. One day a CTR employee suggested a name for a new company newsletter, International Business Machines. Watson realized that the name described the company itself, and from that day forward the company became known as IBM. Id. at 40-41.

[59] According to Professor Roger Roots, at the time the U.S. Constitution was ratified, “there were no professional police officers to enforce criminal laws. Criminal law enforcement was mostly the province of private citizens, who conducted investigations, made arrests and initiated complaints in criminal court. Constables and sheriffs were not salaried but instead paid by user fees.” Roger Roots, “The Originalist Case for the Fourth Amendment Exclusionary Rule,” 45 Gonzaga L. Rev. 1 (2010), at 11.

[60] In the late 19th century, the Pinkerton Detective Agency, “the most notorious private police force available for hire,” was larger than the U.S. Army. Robert Justin Goldstein, Political Repression in Modern America From 1870 to 1976 (University of Illinois Press, Illinois Edition, Urbana and Chicago, 2001), at 12.

[61] Mapp v. Ohio, 367 U.S. 643 (1961).

[62] As Goldstein notes, “In many cases, local police and state militia indiscriminately shot and killed strikers. For example, during a strike for an eight-hour day in Milwaukee in 1866, state militia opened fire without provocation on a crowd of demonstrators, killing five and breaking the back of the strike.” Robert Justin Goldstein, Political Repression in Modern America, at 15. In New York City on January 13, 1874, police brutally attacked over seven thousand demonstrators at Tompkins Square,” who “were given no real warning before police attacked them with clubs and horses.” Id. at 27. Following the Haymarket Square bombing of May 4, 1886, in which a bomb was thrown anonymously into police ranks from among McCormick strikers, the Chicago police quickly

arrested about one hundred fifty persons, most of whom were arrested without warrant and held for hours without charges. The police claimed to have discovered bombs all over the city although in fact most of them “were either non-existent or had been planted there by the police. The chief of the Chicago police later testified that the police captain in charge of the investigation, Michael J. Schaak, “wanted to keep things stirring. He wanted bombs to be found here, there all around, everywhere…After we got the anarchist societies broken up, Schaak wanted to sent [sic] out men to organize new societies right away.” One of the major anarchist papers in Chicago was shut down for three days and allowed to appear again only on the understanding it would be shut down if it carried inflammatory articles.

Id. at 39.

[63] See, e.g., Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name: The Re-Enslavement of Black Americans from the Civil War to World War II (Anchor Books, 2008).

[64] See U.S. Marshals Service, “The Judiciary Act of 1789: Charter for U.S. Marshals and Deputies,” available at https://www.usmarshals.gov/who-we-are/history/historical-reading-room/judiciary-act-of-1789-charter-us-marshals-and-deputies (viewed October 24, 2024).

[65] See U.S. Marshals Service, “United States Marshals and their Deputies, 1789-1989,” available at https://www.usmarshals.gov/who-we-are/history/historical-reading-room/lawmen-united-states-marshals-and-their-deputies-1789-1989 (viewed October 24, 2024).

[66] Frederick M. Kaiser, “Origins of Secret Service Protection of the President: Personal, Interagency and Institutional Conflict,” Presidential Studies Quarterly, Vol. 18, No. 1 (Winter 1988), pp. 101-127, at 106, available at www.jstor.org (viewed May 6, 2024). Kaiser notes that no evidence exists for Secret Service protection for Cleveland prior to 1894, and “[f]urthermore, there is no evidence or even conjecture that such security arrangements existed for Chester A. Arthur, who succeeded [President Garfield, assassinated in 1881], or for Benjamin Harrison, who had served between Cleveland’s two terms.” Id. at 107.

[67] Kaiser at 108. FN 33 is statement by Secret Service Chief John Wilkie in Sundry Civil Appropriations for FY 1910, p. 227. In 1902 there was serious support in the U.S. Senate for a permanent military guard,

when Congress first convened after McKinley’s assassination and the Senate approved legislation assigning the protective duty to the Secretary of War….Intense opposition surfaced, however, against the exclusive or even predominant use of the military, especially under the special authority granted to the Secretary of War….For some in Congress, the adverse symbolism and implications for civilian, democratic government became insurmountable obstacles to a military guard. It was portrayed as befitting an emperor or monarch, not a President.

Kaiser at 114 (citing, inter alia, remarks by Senators Mallory and Carmack, Congressional Record, v. 35, 1902, pp. 3050 and 3056).

[68] Paul Foos, Short, Offhand, Killing Affair: Soldiers and Social Conflict During the Mexican-American War, The University of North Carolina Press, 2002), 152-53 (quoting CITE)

[69] Robert Justin Goldstein, Political Repression in 19th Century Europe (Croom Helm Lt. Kent, 1983), at 194.

[70] Robert Justin Goldstein, Political Repression in 19th Century Europe (Croom Helm Lt. Kent, 1983), at 287-88. The U.S. Congress did at various points increase funding for state militia, which were then used to repress labor union and anarchist activism. “Appropriations for the militia by state in 1891 correlated .59 with numbers of workers involved in strike activity during 1881-86, an exceptionally high correlation, considering all of the influences which might affect state militia appropriations.” Robert Justin Goldstein, Political Repression in Modern America, at 41.

[71] Mangesh Sawant, “Why China Cannot Challenge the US Military Primacy,” Journal of Indo-Pacific Affairs, Air University Press, Dec. 13, 2021, at https://www.airuniversity.af.edu/JIPA/Display/Article/2870650/#:~:text=The%20Opium%20Wars%20were%20fought,the%20world's%20most%2Dpowerful%20navy.&text=The%20British%20consisted%20of%2020%2C000,dozen%20modern%20Royal%20Navy%20warships (viewed October 3, 2024).

[72] David Todd, A Velvet Empire: French Informal Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century, 104 (Princeton University Press, 2021).

[73] The Scramble for Africa started in the 1860s when the French and the British begin the systematic exploration of West Africa. This culminated in the Berlin Conference of 1884-85, hosted by Otto von Bismarck, at which the European powers divided Central Africa amongst themselves and created principles for the partitioning of the rest of the continent. Stelios Michalopoulos and Elias Papaioannou, The Long-Run Effects of the Scramble for Africa, American Economic Review 2016, 106(7), 1802-1848, at 1807. France occupied Saigon in 1859. In 1863 French naval officers established a protectorate over Cambodia. In 1867 France consolidated all of its holdings inot their colony of Cochin China. Sally Frances Low, Colonial Law Making: Cambodia under the French (NUS Press, 2024), at 37. Britain annexed Upper Burma in 1885, causing a war of resistance that lasted until the early 1890s. In 1895 Britain incorporated Selangor, Perak, Negeri Sembilan and Pahang into the Federated Malay States (FMS). Id. at 51.

[74] McGinty, 100.

[75] McGinty, 118.