The Spanish-American War of 1898: Origins and Consequences

Section II.A of my book/very long article

A. The Spanish-American War: Origins and Consequences

The Spanish-American War of 1898 was instigated over Cuba. Then, as now, there was a large and vocal group of Cuban-American émigrés, mostly in New York and Florida, who were able to command national attention in the United States to their allegations of misrule in their homeland.

Cubans had been agitating for independence from Spain since 1868, including through military action, but had struggled to unite under a single banner.[1] A liberation army was gradually organized overseas through the Cuban Junta, a governing council for the Cuban Revolutionary Party founded by émigré Jose Martí that was headquartered in New York City.[2] In 1894, Martí decided to step up planning for an invasion, as he watched with concern the Congressional debates over the possible annexation of Hawai’i and wanted to make sure Cuba was liberated from Spain before it became the next U.S. colony.[3] The liberation army, finally constituted in the spring of 1895, sailed to Cuba out of Florida, Costa Rica and Haiti, constituted their land forces near Santiago de Cuba, and proceeded to wreak havoc across the Cuban countryside with relentless guerrilla tactics.[4]

In February 1896, the Spanish government, still unyielding in Cuban demands for independence, adopted a scorched-earth strategy and issued a series of reconcentración decrees, forcing the entire rural population of Cuba to relocate to within fortified areas behind Spanish defensive lines. Their houses were then destroyed along with any crops remaining in the fields, in order to starve out the opposing forces.[5] By 1898, one-third of Cuba’s population had been forced into these concentration camps, where over 400,000 Cubans would eventually die of famine or disease.[6]

These atrocities received copious coverage from the Hearst family of U.S. newspapers back in New York City.[7] Despite the rebels carrying out their own excesses, the reaction of the public within the United States “instinctively backed the rebels and cast Spain in the role of brutal oppressor, her boot on the neck of a ragged people struggling against a European tyranny.”[8] The U.S. Government under President McKinley was extremely cautious about the possibility of direct intervention and military conflict against Spain, instead repeatedly offering Spain its services as a mediator with Cuban insurrectionist forces. Spain, however, dismissed these diplomatic overtures out of hand and maintained its absolute opposition to Cuban independence.[9]

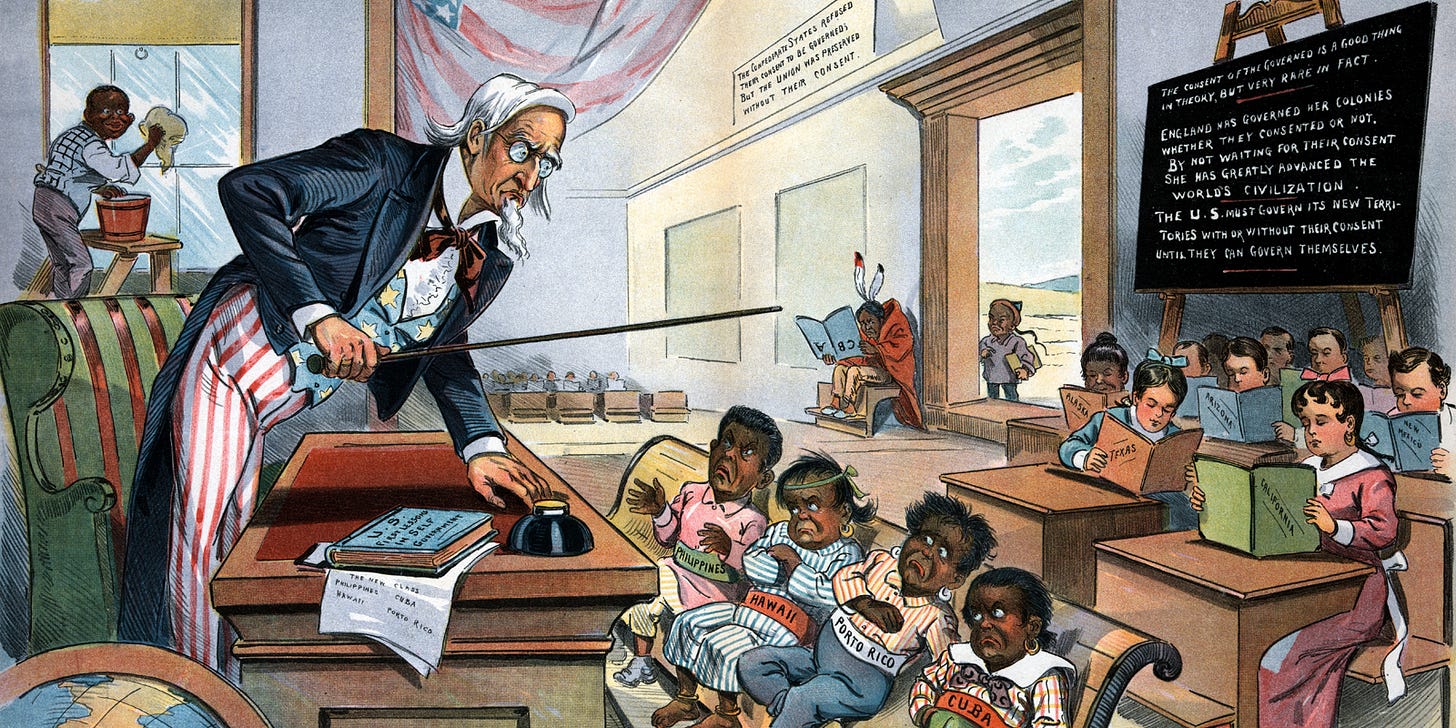

After street riots broke out in Havana in January 1898, the U.S. Consul posted there, Fitzhugh Lee (the U.S. Government’s most helpful source of human intelligence on Cuba at that time), began to engage in more serious discussions with officials back in Washington about sending a U.S. warship to sit in the harbor at Havana in order to safeguard U.S. interests.[10] The U.S.S. Maine arrived on January 25, where it was received peacefully and respectfully, if not enthusiastically, by Spanish forces.[11]

On the night of February 15, 1898, the Maine then mysteriously and dramatically exploded in the Havana harbor and sank, causing 261 fatalities. While both then and now it is generally believed among experts that the explosion was an accident, several tabloid newspapers in the United States immediately blamed Spain for an intentional attack on the vessel.[12] The destruction of the Maine “did not plunge the nation immediately into war, yet it did create an atmosphere in which escape from war was virtually impossible unless one of the three parties—Spain, the United States, or the Cuban Junta—blinked. None did.”[13]

By June 13, 1898, the United States had formally declared war on Spain,[14] and 17,000 men of the Fifth Army Corps were on their way from Tampa Bay, Florida, to Cuba, carried by approximately 30 steamers and escorted by a naval covering force.[15] But an amendment to the April U.S. Senate resolution in favor of war had been added by Senator Henry Teller of Colorado, explicitly disclaiming “any disposition or intention [on behalf of the United States] to exercise sovereignty, jurisdiction or control over [Cuba].”[16] Senate supporters of the amendment included “those who opposed annexing territory containing large numbers of blacks and Catholics, those who sincerely supported Cuban independence, and representatives of the domestic sugar business, including [Teller], who feared Cuban competition.”[17] The successful passage of the Teller Amendment eliminated from the outset the possibility, entertained since the days of the Louisiana Purchase,[18] that the United States would ever annex Cuba. The U.S. Navy nonetheless took immediate notice, upon arrival, of the attractiveness of Guantánamo Bay as a forward repair and coaling station for its fleet.[19]

No such restriction was imposed, however, on the miscellaneous other Spanish territories that the United States moved to seize immediately upon its declaration of war: Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines. In fact, by May 2, 1898, the U.S. Asiatic Squadron, under the command of Commodore George Dewey, had already consolidated itself at Hong Kong, sailed to the Philippines, and won a decisive battle against the Spanish Navy at Manila Bay.[20] This victory had come about despite the fact that Dewey regarded the Philippines as “terra incognita”; the most recent documentation he could obtain about them from the Navy Department dated from 1876. While docked at Hong Kong, Dewey had sent his aides to buy every available chart of the “Eastern Archipelago.”[21]

Dewey’s limited human intelligence on the Philippines came to him courtesy of the U.S. Consul General in Singapore, who had made contact there with a 29-year-old Filipino exile named Emilio Aguinaldo. Aguinaldo claimed to be the president of a rebel provisional government willing to join forces with the Americans for military operations against Spain, but he wanted to know if the United States in return would guarantee the Philippines their independence. From his interactions with both the Consul General and later Dewey, Aguinaldo came away with the impression that, as Cuba could not legally be annexed by the United States, neither would the Philippines. Dewey would later tell a U.S. Senate committee, “They seemed to be all very young, earnest boys. I did not attach much importance to what they said or to themselves.”[22] When asked why Dewey allowed Aguinaldo to return to the Philippines on May 19 following the naval victory over the Spanish, Dewey replied, “God knows. I don’t know. They were taking my time about frivolous things. I let [him] come over as an act of courtesy, just as you sometimes give money to a man to get rid of him…”[23]

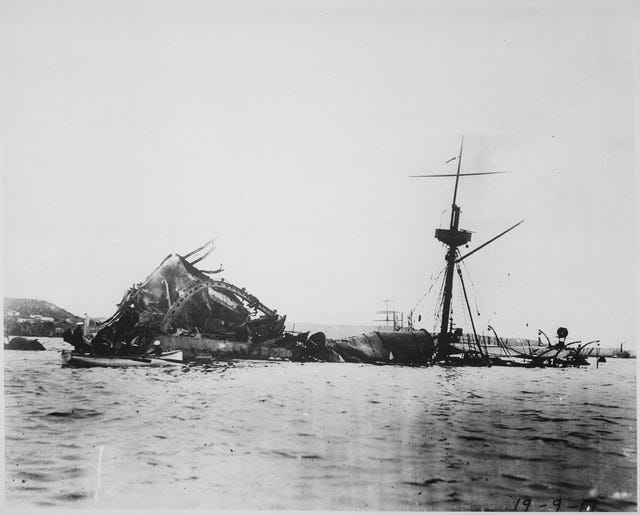

Dewey’s conundrum was that the land forces he needed to now occupy the city of Manila, having destroyed the Spanish fleet in the bay, were mostly on their way to Cuba, their ranks including former Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, who had not only given Dewey his mission in the Philippines,[24] but was the person who had politically engineered Dewey’s appointment to the Asiatic Fleet to begin with.[25] On April 23, President McKinley had issued a public call for military volunteers to help invade Cuba, with the power to enlist entire volunteer units who self-organized; the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry were to become the most famous of these, known now by their nickname the “Rough Riders.”[26] Roosevelt decided that his destiny lay with the “Rough Riders,” and by mid-May he was already in Tampa, Florida awaiting deployment to Cuba as the regiment’s second-in-command under Brigadier General Leonard Wood, having resigned from the Navy to accept a commission as an Army lieutenant colonel.[27] He would soon thereafter pass into legend leading the Rough Riders against a Spanish entrenchment on a heroic if somewhat insane charge up San Juan Hill,[28] returning from Cuba a war hero. By 1900 he would be President McKinley’s vice-presidential running mate, and then finally, upon McKinley’s assassination in 1901, President of the United States.

Dewey cabled to Washington on May 13, 1898, that he would need 5000 troops to take the city of Manila (which he also noted was running out of food), estimating with somewhat remarkable accuracy that the Spanish forces in the local area were about 10,000 in number.[29] In Washington, Army leadership recommended 15,000-25,000 men instead, noting that the Philippines, unlike Cuba, was “a territory 7,000 miles from our base,” and “inhabited by 14,000,000 [actually, around 8 million to 10 million], the majority of whom will regard us with the intense hatred born of race and religion.”[30] The first American expeditionary forces did not arrive in the Philippines until June 30.[31]

By then, a crucial gap in understanding had opened up between U.S. forces and Emilio Aguinaldo. Aguinaldo, now on the ground near Manila, had issued two edicts on May 24, the first of a series of independence proclamations addressed to the Filipino people.[32] In late May, insurgent forces began active military operations against the Spanish using a shipment of rifles and ammunition purchased by the U.S. Consul in Hong Kong and paid for in Mexican gold pesos supplied by Aguinaldo. Aguinaldo soon had 14,000 troops who had deserted from the Spanish side. As far as Dewey was concerned, the support Aguinaldo was supplying as Dewey waited on U.S. land forces was similar to how “the negroes [in the U.S. South] helped us in the Civil War.”[33] He also couldn’t help but notice that the rebels were “whipp[ing] the Spaniards battle after battle.”[34] Dewey complained to Washington that Aguinaldo was starting to get “a big head,”[35] but at the same time forwarded along to Washington Aguinaldo’s June 18 Philippine Declaration of Independence, with a note stating in part “In my opinion these people are superior in intelligence and more capable of self-government than the natives of Cuba, and I am familiar with both races.”[36] The former U.S. consul at Manila, however, separately cabled the State Department that the insurgent leadership “all hope the Philippines will be held as a colony of the United States.”[37]

Aguinaldo, for his part, couldn’t imagine that the United States would hold onto the Philippines as a colony, based on everything U.S. officials on the ground were telling him, particularly Dewey.[38] And yet even as early as mid-May 1898, when U.S. Army leaders in Washington were calculating the need for 25,000 troops to pacify “14,000,000” people across the entire archipelago, there were already signs of an evident shift in thinking, from a mission of simple military occupation of the port city of Manila in support of a war against Spain centered in Cuba, to something else entirely. What was causing this shift in U.S. policy?

What Dewey did not fully appreciate was the significance of this terra incognita to a range of European imperial powers beyond Spain. At the height of the Spanish empire, Manila had been a key part of the Spanish galleon trade, routing goods from East Asia into Acapulco in exchange for Mexican silver. But when the Spanish empire collapsed in the early 18th century, leaving only the Philippines, Cuba, Guam, Puerto Rico and a handful of other Pacific Islands under Spanish control, British capitalists, with Spain’s permission, had moved into the Philippines, establishing production facilities, merchant companies, production facilities, and joint American-British trading companies investing in sugar, hemp, and indigo farms.[39]

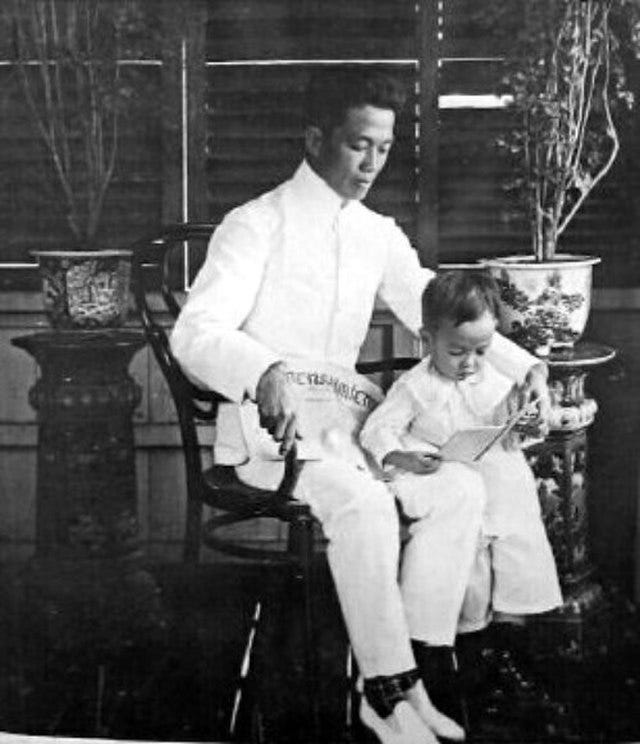

Filipino Creoles and Chinese Filipino elites had then leveraged the British presence in India, the Dutch in Java, the French in both India and the Mascarenes, and the Portuguese throughout South Asia to create a new mercantile order of their own. The British opium trade between India and China had contributed greatly to this new market.[40] Aguinaldo had come from a well-to-do landowning family of mixed Chinese-Tagalog ancestry.[41] Aguinaldo’s fellow revolutionary, Apolinario Mabini, was the child of an illiterate vendor, paralyzed by polio, whose academic brilliance was recognized early on by Spanish educators; he eventually obtained a law degree and was by 1898 Aguinaldo’s “Dark Chamber,” his “right-hand man, the writer of his most important papers, the intellect, the planner without whose instructions Aguinaldo seldom spoke or acted on any matter of state.”[42]

Between the mid- and late-19th century, Germany as well was emerging as a colonial power, and by the 1890s both Germany and Russia were increasingly challenging British supremacy in East Asia.[43] The Germans, in particular, had built up an impressive navy—inspired in large part by U.S. naval theorist Arthur Thayer Mahan—and were searching for a naval base in East Asia. [44] From Dewey’s vantage point, it was evident even before he had sailed from Hong Kong that the British were being incredibly generous; “Dewey’s squadron was supplied in large part from British territories, and but for British goodwill, he would not have been able to communicate by cable with Washington through Hong Kong.”[45] By contrast, the Germans were being highly annoying. By June 12 the Germans had three warships at Manila (the British had two, the French and Japanese one each), constantly moving about and breaching Dewey’s naval blockade, and apparently meddling with insurgent activity near Subic Bay.[46]

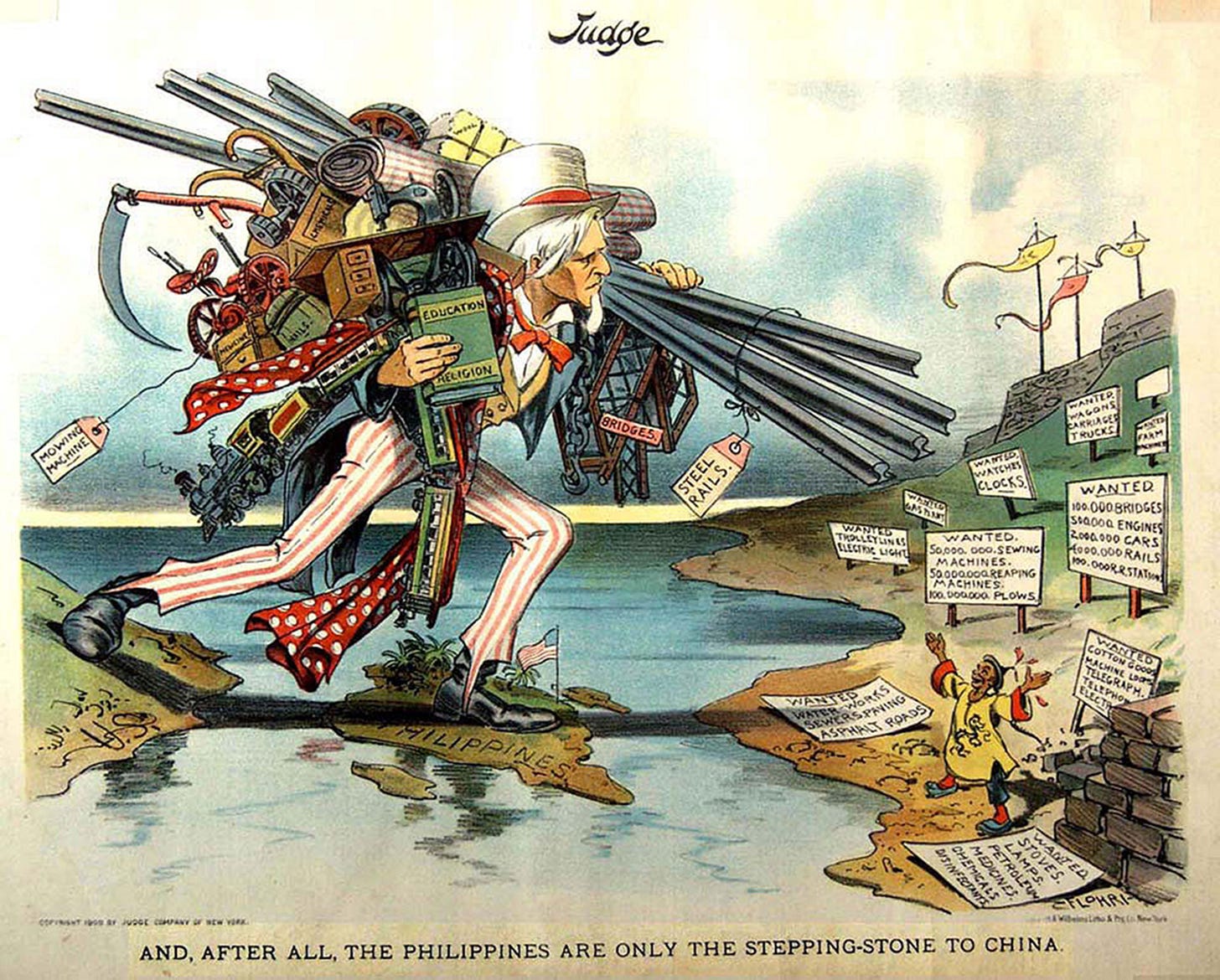

From British communications with U.S. officials in Washington and London,[47] it gradually became clear that the British wanted the United States to annex the entire Philippines from Spain in order to subvert German designs on the archipelago.[48] Japan, by then an emerging imperial power in its own right, was also “quick to advise the United States to keep the Philippines,” as it had “similar apprehensions that its main rival, Russia, might gain some advantage if the United States retreated or partitioned the islands.”[49] France, by contrast, was advising U.S. diplomats that the United States would “do well to keep out of the quarrel” (between England and Germany) and should return the islands to Spain. From all of the information available to McKinley between Dewey’s reports and diplomatic communications, it was evident that “a fierce and probably violent scramble would erupt between the great powers over the Philippines if the United States withdrew.”[50]

What all the imperial powers could agree upon was that under no circumstances should control of the Philippines be handed to the native insurgents. When U.S. land forces finally began to arrive in Manila, Spanish authorities in Manila communicated to the British and the Belgian consuls that they were “willing to surrender to white people but never to N—s.”[51] Aguinaldo, on the other hand, was so determined to enter the city of Manila that, when the Spanish forces finally did surrender to the United States on August 12, a U.S. regiment literally had to push his forces out of the way, whereupon the insurgents began instead to gradually encircle the city with entrenchments.[52] Shortly thereafter, the Spanish flag was lowered and the U.S. flag raised over Manila. In an August 17 cable to Dewey and Army Major General Wesley Merritt, President McKinley stated explicitly, “There must be no joint occupation with the insurgents.”[53]

The insurgents could only notice and grow concerned about the “glacial silence” coming out of Washington:

The Filipinos wondered if they were about to be handed over from one master to another. Hastily they pressed their new government into being, although its congress would not convene for some weeks. There was little to distinguish it from the American system. The president was granted somewhat greater power than his U.S. counterpart. The legislative branch was unicameral. Departmental secretaries—Foreign Relations, Marine and Commerce, War, Public Works, Police, Justice, Instruction, Hygiene, and Treasury—were all appointed by the executive and corresponded closely to U.S. cabinet posts. The body of jurisprudence was taken almost intact from the code of English-speaking peoples. Congress itself was to be composed of representatives elected by popular vote in each province. All of this was largely the brain child of Apolinario Mabini…

Several days after its proclamation, the document was signed by ninety-eight Filipino officials and one Artillery Colonel L.M. Johnson of the United States Army.[54]

Back in Washington, McKinley purportedly had a “natural revulsion” to the idea of annexing the Philippines, but as the days wore on following the August 12 armistice between the United States and Spain, he simply saw no viable alternative. According to his own account, he turned to nightly prayer.

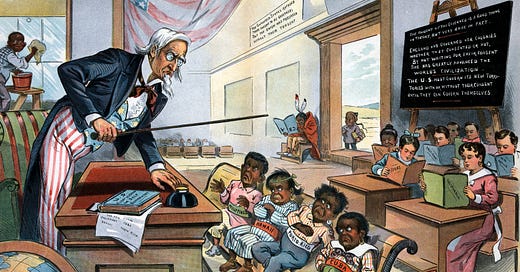

“And one night late,” the president confided to his fellow Methodists, “it came to me this way…(1) That we could not give them back to Spain—that would be cowardly and dishonorable; (2) that we could not turn them over to France or Germany—our commercial rivals in the Orient—that would be bad business and discreditable; (3) that we could not leave them to themselves—they were unfit for self-government—and they would soon have anarchy and misrule over there worse than Spain’s was; and (4) that there was nothing left to do but to take them all, and to educate the Filipinos, and uplift and civilize and Christianize them…”[55]

McKinley’s view was further reinforced by that of General Francis V. Greene, who returned from the Philippines and visited the White House five times in the fall of 1898. During that same fall, by contrast, two of Dewey’s subordinate officers undertook an extended reconnaissance of northern Luzon, speaking with hundreds of people, and returned generally pleased with “the efficiency of Aguinaldo’s government and…the law-abiding character of his subjects…On one point they seem united, that whatever our government may have done for them, it has not gained the right to annex them.”[56] Greene, however, believed that Aguinaldo would need “the help of some strong nation,”[57] and that simply granting the Filipinos independence would be like tossing a “golden apple of discord” among the rival imperial powers. In this regard, the recent collapse in 1888 of a tripartite agreement over Samoa between the United States, Germany and Great Britain, which had nearly resulted in a war “seemed to prove the fragility and perilous awkwardness of such a policy.”[58]

The peace treaty between the United States and Spain, signed on December 10, 1898, required Spain to relinquish Cuba (which became officially “independent” of the United States as per the Teller Amendment, with a long and complicated relationship to follow); cede Puerto Rico, Guam and a few other islands outright to the United States; and surrender the entire Philippine archipelago to the United States, its precise linear boundaries described in quintessential Westphalian fashion, in exchange for twenty million dollars.[59] In order to be ratified, the treaty then needed the advice and consent of two-thirds of the U.S. Senate. At this point, English poet Rudyard Kipling helpfully published his poem White Man’s Burden in the New York Sun, where it ran on February 1, 1899:

Take up the White Man's burden—

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives' need;

To wait in heavy harness

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child…[60]

After some deliberation (discussed supra Part 1), the U.S. Senate provided its required advice and consent to the treaty only five days later, on February 6, 1899, by a vote of 57 to 27.

Senator Joseph Foraker of Ohio immediately began to draft legislation for civilian government in Puerto Rico, where the local inhabitants had offered very little resistance—indeed, had largely welcomed U.S. rule—and where the most contentious issue would turn out to be whether tariffs would be imposed on Puerto Rican sugar. The issue of sugar tariffs became so politically charged, in fact, that the final version of the Foraker Act (officially named the Organic Act of Porto Rico of 1900) set the stage for the first of the Insular Cases in 1901, as business interests in Puerto Rico immediately challenged the constitutionality of holding U.S. territories that somehow were not part of the United States for purposes of customs and duties.[61]

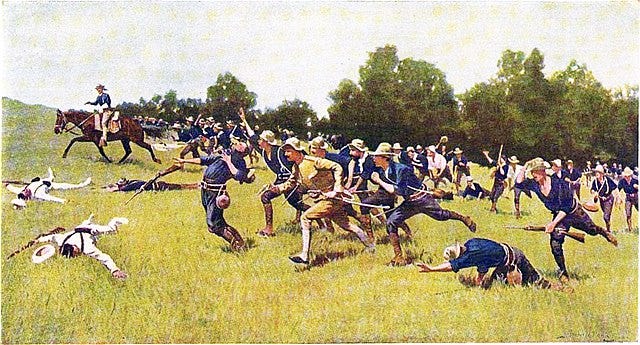

On February 4, 1899, just two days before the Senate voted on the Treaty of Paris, “word came that an exchange of shots between American and Filipino outposts had widened into a general engagement in the Philippines. It was the beginning of what became the two-year Philippine insurrection, as bloody a colonial fight as was ever fought.”[62] The United States had just inherited 7,641 islands, occupied at that time by approximately 10 million people belonging to 84 separate tribes; of these, only 8 were regarded as “civilized” by the standards of the time.[63] Whitelaw Reid, the former U.S. ambassador to France who had served on McKinley’s peace commission to negotiate the treaty with Spain, spoke later to the Lotus Club in New York about Aguinaldo, “that irritation of a Malay half-breed” who led the insurrection against the United States, noting, “nobody ever doubted that they would give us trouble. That is the price nations must pay for going to war, even in a just cause.”[64]

[1] Ivan Musicant, Empire by Default: The Spanish American War and the Dawn of the American Century (Henry Holt and Company, New York, 1998), at 40.

[2] Musicant, at 45-47.

[3] Musicant, at 47.

[4] Musicant, at 48-49.

[5] Musicant, at 69.

[6] Public Broadcast System (PBS), “Crucible of Empire,” Timeline, at https://www.pbs.org/crucible/frames/_timeline.html (viewed October 10, 2024).

[7] Public Broadcast System, “Crucible of Empire: Yellow Journalism,” at https://www.pbs.org/crucible/frames/_journalism.html (viewed October 10, 2024).

[8] Musicant, at 78.

[9] Musicant, at 106-110.

[10] Musicant, at 118-19.

[11] Musicant, at 121-36. A second cruiser, the Montgomery, was sent to Matanzas, where its arrival was “hailed with delight by all classes” until the starving population realized that the ship was not in fact there to bring them food from the United States). Id.

[12] Musicant, 137-49.

[13] Musicant, 151-52.

[14] Musicant, 190.

[15] Musicant, 274.

[16] Quoted in Musicant, at 186.

[17] George C. Herring, From Colony to Superpower: U.S. Foreign Relations since 1776 (Oxford University Press, 2008), at [PAGE CITE].

[18] Thomas Jefferson once wrote, “I have ever looked on Cuba as the most interesting addition which could ever be made to our system of States.” In 1823, the year the U.S. first articulated the Monroe Doctrine, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams said he found it “scarcely possible to resist the conviction that the annexation of Cuba…will be indispensable to the continuance and integrity of the United States.” Quoted in Musicant at 78.

[19] Musicant, 325-26, 347-49.

[20] Musicant, 191-234.

[21] Musicant, 202.

[22] Musicant, 197.

[23] Musicant, 547.

[24] Musicant, 193.

[25] Musicant, 110-14.

[26] Congress was only willing to increase the size of the regular U.S. Army to 62,527, and that only temporarily, as a wartime measure. McKinley additionally asked for 125,000 volunteer soldiers to help wage the war against Spain. This number would have exceeded the total manpower of the U.S. National Guard at that time and was unattainable; Buffalo Bill Cody instead offered his own helpful suggestion in an article entitled “How I Could Drive Spaniards from Cuba with Thirty Thousand Indian Braves.” Musicant, 244-6.

[27] Musicant, 269.

[28] Musicant, 415-19.

[29] Musicant, 542.

[30] Musicant, 543.

[31] Musicant, 554. Along the way, the cruiser U.S.S. Charleston was ordered to seize the Spanish outpost of Guam using whatever force necessary. On June 20, the ship arrived at the Guam harbor of San Luis D’Apra to find no Spanish ships and some abandoned forts. It fired a few shots, at which point a Spanish boat carrying a military officer approached the Charleston. It quickly became evident that the officer, a Spanish Army surgeon, was unaware that the United States was at war with Spain, Guam’s last news from Manila having arrived in mid-April. The U.S. naval forces took 56 Spanish marines as prisoners-of-war and hoisted the U.S. flag over Fort Santa Cruz. The ships then proceeded to Manila, as “[t]he few native troops on the island were overjoyed at being relieved of their arms and in grateful appreciation bestowed their buttons and badges on landing force.” Id. at 544-45. Guam remains a U.S. territory to this date; residents of Guam were granted U.S. citizenship by statute in 1950; they have representation in the U.S. House of Representatives but no vote in Congress. See https://www.doi.gov/oia/islands/guam (viewed October 19, 2024).

[32] Musicant, 548.

[33] Musicant, 550.

[34] Musicant, 551.

[35] Leon Wolff, Little Brown Brother: How the United States Purchased and Pacified the Philippine Islands at the Century’s Turn (1961), at 72.

[36] Leon Wolff, Little Brown Brother: How the United States Purchased and Pacified the Philippine Islands at the Century’s Turn (1961), at 73.

[37] Musicant, 546.

[38] See, e.g., Musicant at 548, quoting Dewey’s remarks years later to his autographical ghostwriter: “Our government is not fitted for colonies. There will be resistance in Congress…We have ample room for development at home. The colonies of European nations are vital to their economic life; ours could not be.” Aguinaldo, who had many conversations with Dewey, took away from Dewey’s assurances that the United States was “exceedingly well off as regards territory” and came away with no reason to entertain doubts “about the recognition of the independence of the Philippines by the United States.”

[39] Alvin A. Camba and Maria Isabel B. Aguilar, “Sui generis: The Political Economy of the Philippines during the Spanish Colonial Regime,” in Comparing the Legacies of Spanish Colonialism in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, Hans-Jürgen Burchardt, Johanna Leinius, eds., University of Michigan Press, 2022, at 134.

[40] Josep M. Fradera, “Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and the Crisis of the Great Empire,” in Comparing the Legacies of Spanish Colonialism in Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines, Hans-Jürgen Burchardt, Johanna Leinius, eds. (University of Michigan Press, 2022), at 53.

[41] Leon Wolff, Little Brown Brother: How the United States Purchased and Pacified the Philippine Islands at the Century’s Turn (1961), at 28.

[42] Wolff, 74.

[43] Turan Kayaoglu, Legal Imperialism: Sovereignty and Extraterritoriality in Japan, the Ottoman Empire, and China (Cambridge University Press, 2010), 70.

[44] Turan Kayaoglu, Legal Imperialism: Sovereignty and Extraterritoriality in Japan, the Ottoman Empire, and China (Cambridge University Press, 2010), 71.

[45] Musicant, 548.

[46] Musicant, 556-64.

[47] On May 8, 1898, just one week after Dewey’s victory at Manila Bay, U.S. Ambassador Hay in London notified Washington of unofficial peace feelers from the British government, which had no authorization whatsoever to intervene on behalf of Spain but seemed to want to “take a prominent part, if needed, in the work of pacification.” Musicant, 587.

[48] Musicant, 616-17.

[49] Eric T.L. Love, Race over Empire, Racism and U.S. Imperialism, 1865-1900 (North Carolina Press, 2004), at 167.

[50] Eric T.L. Love, Race over Empire, at 168.

[51] Musicant, 569.

[52] Muiscant, 578-79. In the end, the U.S. had sent 10,900 troops of the Eighth Army Corps to Manila to seize the city from 13,000 Spanish soldiers; meanwhile, the insurgents under Aguinaldo numbered 15,000 and ended up encircling the city with entrenchments outside its walls. Manila at that time had about 250,000 residents. Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 63-64.

[53] Musicant, 583.

[54] Leon Wolff, Little Brown Brother: How the United States Purchased and Pacified the Philippine Islands at the Century’s Turn (1961), at 73-74.

[55] Quoted in Eric T.L. Love, Race over Empire, at 166. It apparently had somehow escaped McKinley’s attention that 95 percent of Filipinos at that time, including Aguinaldo, were Roman Catholics. The other 5 percent were Muslim. Bartholomew H. Sparrow, The Insular Cases and the Emergency of American Empire (University Press of Kansas, 2006), at 36.

[56] Musicant, 584.

[57] Musicant, 584.

[58] Eric T.L. Love, Race over Empire, at 176. American Samoa remains an unincorporated territory of the United States, and its residents are not automatically entitled to U.S. citizenship as per the Insular Cases, a denial that they challenged most recently before the U.S. Supreme Court in 2022; see supra Part I Note 1.

[59] The Philippines islands are described in Article III of the treaty as follows:

A line running from west to east along or near the twentieth parallel of north latitude, and through the middle of the navigable channel of Bachi, from the one hundred and eighteenth (118th) to the one hundred and twenty-seventh (127th) degree meridian of longitude east of Greenwich, thence along the one hundred and twenty seventh (127th) degree meridian of longitude east of Greenwich to the parallel of four degrees and forty five minutes (4 [degree symbol] 45']) north latitude, thence along the parallel of four degrees and forty five minutes (4 [degree symbol] 45') north latitude to its intersection with the meridian of longitude one hundred and nineteen degrees and thirty five minutes (119 [degree symbol] 35') east of Greenwich, thence along the meridian of longitude one hundred and nineteen degrees and thirty five minutes (119 [degree symbol] 35') east of Greenwich to the parallel of latitude seven degrees and forty minutes (7 [degree symbol] 40') north, thence along the parallel of latitude of seven degrees and forty minutes (7 [degree symbol] 40') north to its intersection with the one hundred and sixteenth (116th) degree meridian of longitude east of Greenwich, thence by a direct line to the intersection of the tenth (10th) degree parallel of north latitude with the one hundred and eighteenth (118th) degree meridian of longitude east of Greenwich, and thence along the one hundred and eighteenth (118th) degree meridian of longitude east of Greenwich to the point of beginning.

Spain, and United States Department Of State. A treaty of peace between the United States and Spain. Washington, Govt. print. off, 1899. Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/21003706 (viewed October 21, 2024). At the peace talks, Spain objected strongly to the U.S. annexation of Puerto Rico, but the residents of Puerto Rico themselves seemed to have welcomed the transfer of sovereignty from Spain to the United States. Shortly after U.S. forces invaded the city of Ponce, “[f]ive companies of the municipal fire brigade paraded before them in their honor,” signs reading “English Spoken Here” began appearing outside local shops, and the wealthier local citizens even opened a Red Cross hospital for the U.S. Army at their own expense. Ivan Musicant, Empire by Default, 532-33.

[60] Notes by Mary Hamer, The White Man’s Burden, available at https://www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/readers-guide/rg_burden1.htm (viewed October 22, 2024). See also Senator Tillman’s remarks to the Senate about the poem, delivered February 7, 1899, available at https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/gilded/empire/text7/tillman.pdf (viewed October 22, 2024).

[61] Bartholomew H. Sparrow, The Insular Cases and the Emergency of American Empire (University Press of Kansas, 2006), at 37.

[62] Musicant, 628.

[63] Eric T.L. Love, Race over Empire, 179.

[64] Musicant, 630.