Two of my Christmas gifts: How to Hide an Empire and G-Man, a biography of J. Edgar Hoover.

I also got Injinji socks, but you're probably less interested in hearing about those

When my family was asking me for inexpensive gift ideas a few weeks ago, I had just written to Jennifer Luff to tell her how impressed I was with her scholarship and to forward her this:

I summarized the project I was working on, and to my delight, she wrote me back right away! She had several book recommendations for me, one of which was How to Hide an Empire by Daniel Immerwahr. I told her she was now the third person who had recommended that book to me, and that I had been on a wait list to check out the e-book from the DC Public Library via an app called Libby since November 17 (because apparently we require public libraries to ration e-books for no good reason; between November 17 and Christmas I moved up from 62nd to 47th in line).

She also recommended G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century by Beverly Gage. I don’t usually go for biographies—I tend to think, a la Jared Diamond, that geography is the primary driver of human history, rather than particular personalities—but on Luff’s recommendation, I was willing to check it out. Turns out it won a Pulitzer Prize, so probably a biography I’ll enjoy and that is worth reading. I did very much enjoy Theodore Rex by Edmund Morris (which my wife owns; apparently Teddy Roosevelt has quite a following among antitrust policy wonks), as well as of course Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow. I’ve purchased a few copies of the Hamilton biography for European friends over the years who say they don’t feel like they know enough about early American history. I figure, if they ever want to enjoy the Broadway musical, they’ll appreciate having read the book first, since the lyrics come at you so fast on stage that I have no idea if a non-native-English speaker could possibly make sense of them without some context. (They now have a German language version of the show, can you imagine??)

Anyway, my wife passed these two book recommendations on to family members looking for Christmas gift ideas, so now I can add them to the Jenga pile of books on my nightstand. I started reading How to Hide an Empire on the car ride home and am about 3/4 of the way through. I wanted to make sure I hadn’t missed a single relevant detail about the 1787 Northwest Ordinance or, God forbid, the Spanish-American War, before moving on to 20th century history, which is kicking my ass. I was just getting used to the pace of the 19th century, and then wow, I only got as far as the pre-WWI years and all this shit started happening. I’m even more impressed now with Heather Cox Richardson than I was before. Having encyclopedic knowledge of the 20th century requires a lot of RAM capacity. She just posted something on the pre-1980s history of pro wrestling and tied it into Hannah Arendt’s Origins of Totalitarianism, for God’s sakes.

How to Hide an Empire is turning out to be a useful guide on How to Write a History Book. Immerwahr says his book’s “main contribution is not archival, bringing to light some never-before-seen document. It’s perspectival, seeing a familiar history differently.” That’s generally also what I’m doing, just reading a huge volume of secondary sources, although in my case the methodology is primarily driven by the fact that I’m at my day job when most of the archives are open for all these discoveries of never-before-seen documents. The main thing I’m doing that may seem somewhat “original” is, with each chapter I research, I make a point of looking for non-white and/or non-Western-authored scholarship. This method has almost never failed to produce startling revelations for me personally, which may tell us something about how seldom white Western scholars think to do that.

As for “seeing a familiar history differently,” I think he generally sees it as I see it; i.e., he actually cares about the “outlying” possessions of the United States, such as those picked up after the Spanish-American War, and wonders aloud why we don’t acknowledge them as part of “the United States.” In doing so, he explores the United States’ own very unique approach to Western imperialism, in which we pretend to still be an anti-colonial republic, which is going to be super useful to me as I progress through the overwhelming amount of material on the 20th century.

What he does way better than me is produce a short, manageable book that someone like my wife might actually read. I know for a fact that there’s a market for the 1200-page tome on World War I by Hew Strachan (and it’s only Volume I!), because that market includes me, but Immerwahr is probably reaching people who were looking for something a wee bit more manageable. It’s a talent I don’t have, which means I can’t make people care about history who don’t already care about it. I literally am starting a podcast next year entitled “Nobody Gives a Shit about the Spanish-American War” based on my wife’s reaction to that particular chapter.

As to why I “can’t” write more like Immerwahr, which I’m sure my wife will ask me if she reads Immerwahr…part of it is, I’m not confident enough to make some of the conclusory statements that Immerwahr does. I’m not sure anyone would accept my assertions if I don’t “show my math.” After all, I have only an undergraduate degree in history; I’m certainly not a history professor. Also, my feeling is, far be it from me to suggest that anyone in U.S. history has ever acted on racist assumptions or motives. So, instead of summarizing or characterizing, I’m just going to show you what they said in Supreme Court holdings and the Congressional Record and let you form your own judgment.

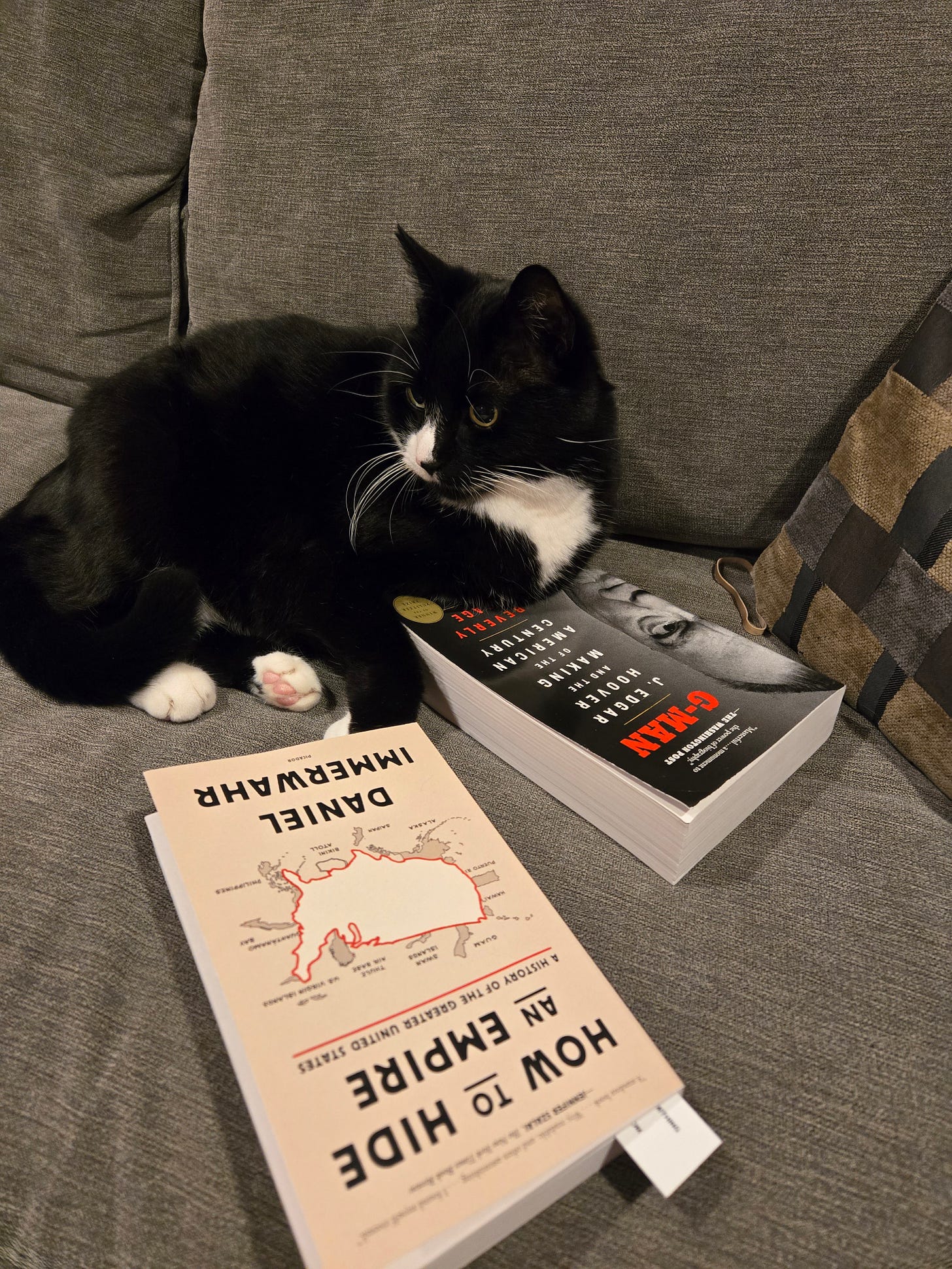

The other book, G-Man, I’ll start after I’m done with Immerwahr, although of course I had to first skip ahead and read everything it has to say about Clyde Tolson.

G-Man is a tome. It also appears to me that Gage has been able to draw upon newly available archives, which again, is super helpful to me given that I have a day job. There’s a certain genre of history book that I’ve found very useful to my research, in which the author’s primary accomplishment is simply being the first person to get into the archives of intelligence agencies. Christopher Andrew has published some enormous works of original scholarship on the British MI5 and the KGB’s “Mitrokhin Archive.” This genre tends to be on the opposite end of the spectrum from Immerwahr in terms of historical analysis and conclusions; they’re mostly going through all these “never-before-seen documents” so the rest of us don’t have to. I totally respect that, as there’s usually only two ways to get into these archives: either you develop such a relationship with the intelligence agency that they designate you their “official biographer,” or you sue them.

There are very few works that can do what Christopher Andrew does, which is get into newly released archival materials about intelligence agencies, and what Immerwahr does, which is to analyze primary and secondary materials to produce supportable conclusions and real insight (one of the few is C.A. Bayly’s Empire and Information: Intelligence Gathering and Social Communications in India, which I highly recommend). Alfred McCoy, in Policing America’s Empire, did the former really well, but, as Jennifer Luff points out, his conclusion that Captain Ralph van Deman brought lessons learned in the Philippines back home in order to construct the U.S. intelligence apparatus ended up a bit overwrought—precisely because McCoy didn’t grapple with the influence of J. Edgar Hoover, who did plenty to create the modern U.S. surveillance state without ever travelling outside the United States for his entire life.

So, I’m really hoping Gage’s Hoover biography will help me sort all this out. I’m reluctant to write much more about U.S. activities during World War I without a firm grip on what this guy Hoover was up to, and not just with Clyde Tolson.

But seriously…look at those two.

So what were the expensive gift ideas?