Personal identification, racism and colonialism

Part 1 of at least 3: The 19th and early 20th centuries

Introduction: What is identity intelligence?

This is a three-part post about what the modern U.S. intelligence community calls “identity resolution” or “identity intelligence.” It was only in the 20th century that the technologies were sufficiently advanced to create reliable Personally Identifiable Information (PII) that was readily retrievable by central authorities. But when and why did human society even develop a need for such technologies? That is the subject of this post, which focuses mostly on the 19th and very early 20th centuries, and as you might expect coming from me, it’s all tied up with racism and colonialism. We will get into World War I and its aftermath next week.

The National Intelligence University (NIU) in Bethesda, Maryland, which provides free undergraduate and graduate programs to the U.S. national security community, has in its 2024-2025 catalogue a course in “identity intelligence.” The course description reads as follows:

“This course provides operational-strategic/national (DoD/interagency/partner nation) understanding of identity intelligence (I2) terms, concepts, doctrine, and associated operations/activities. This includes knowledge of identity modalities, three enabling activities (biometrics, forensics, and DOMEX [document and media exploitation], and identity attributes (biologic, biographic, and behavioral). Students will learn the organizations, missions/functions, technology/tools (current and emerging), databases and analytic tradecraft, and information coordination requirements, including policy and legal considerations. Content spans the two primary I2 functions: identity discovery/reveal (or denying threat anonymity) and protect/conceal.[1]”

NIU also offers an interesting course called “Culture and Identity in an Age of Globalization,” described as follows:

“The highly distributed and dispersed global operations observed in recent years—from Timor to Bosnia, the former Soviet Republics, Baghdad, and Kabul—underscore the importance of conducting uniquely tailored missions in different environments. The pressures of globalization challenge the ability of individuals and nations to maintain ‘identity.’ The mix of cultural groups, languages, religions, customs, and beliefs occurring in nation-states can shape an official identity. However, individuals and nonstate actors also seek to forge their own identities because identification with a particular group provides a sense of belonging, empowerment, and security. The lack of identity among minorities and outsiders can yield exclusion, intolerance, and conflict. The principal focus of this course is to learn to recognize the complexity and dynamics of national, ethnic, cultural, and religious identities. Understanding individual and group identities and practices is key to knowing both one’s adversaries and one’s allies.”[2]

“Identity intelligence” or identity resolution; i.e., the ability to identify an individual to the exclusion of other individuals, is neither an intelligence collection discipline (like SIGINT, HUMINT, GEOINT, OSINT, etc.), nor is it exactly intelligence analysis. It is nonetheless a discipline that underpins much of modern intelligence work, particularly in counterterrorism, which relies heavily on travel records and watch lists. It is also an area, as suggested by the second NIU course above, that requires cross-cultural awareness, as many cultures have family or religious naming conventions that result in repetitive or multiple names,[3] and/or do not attach particular importance to recording or remembering one’s exact date of birth.[4] The West has gone to great lengths to impose its own naming conventions and other personal identifiers on its colonies and on 19th century Ashkenazi Jews,[5] but the insisted-upon changes haven’t always stuck.

The ability to identify an individual to the exclusion of others required a number of technological innovations, many of which only began to become available in the early 20th century. But before those innovations happened, there first had to be a societal need to assign and record immutable identity characteristics to individuals in the first place.

Why would we need to identify someone?

In the pre-modern era, there was no such need, as most people spent their entire lives in a small, rural/agricultural setting and were simply known from birth to death by their local community.

The need for personal identification connected solely to the body, as opposed to a body in a particular fixed place or community, arose from several key transformations in global human relations that occurred in the 19th century: chief among them, the end of slavery, the rise of migrant labor, industrialization, the communications revolution, and the racial concept of nationality that evolved as part and parcel of the modern Westphalian nation-state. (I have written about the Westphalian nation-state and its relationship to colonialism here):

Stephen Krasner’s book Sovereignty: Organized Hypocrisy (1999) articulates four different kinds of sovereignty: (1) international legal sovereignty, meaning international recognition from states; (2) Westphalian sovereignty as the principle of non-interference in another sovereign state’s domestic affairs; (3) domestic sovereignty, meaning, the ability of a state to maintain the monopoly of the use of violence within its territory; and (4) interdependence sovereignty, meaning the capacity of a government to control intra-border movements of any kind. The enforcement of linear, territorial borders demarcating different European states’ sovereignty and their ability to act with autonomy within those boundaries—particularly with regard to their overseas colonies—has been a feature of the Westphalian system since the 1648 Peace of Westphalia.

However, this did not necessarily mean that sovereign states could effectively control, or were even preoccupied with controlling, movement by individuals across these borders. For example, while the early English North American settlement at Jamestown purportedly excluded Roman Catholics, archeologists at Jamestown have unearthed numerous Catholic crucifixes, rosary beads, and medallions.[6] Global travelers of this era might have had, at most, a letter signed by their monarch or other functionary requesting their safe passage through a foreign territory; such letters became known as the “passe port” under the reign of King Louis XIV of France, who liked to sign such letters for his court favorites.[7]

In 1833, Alexis de Tocqueville observed that, in the United States, “[w]here passports do not exist, nothing is easier than to change one’s name…Nothing is easier than to pass from one state to another, the ties between the various states being strictly political, there is no central power to which the police officers might refer to obtain information respecting the previous life of an indicted person…”[8]

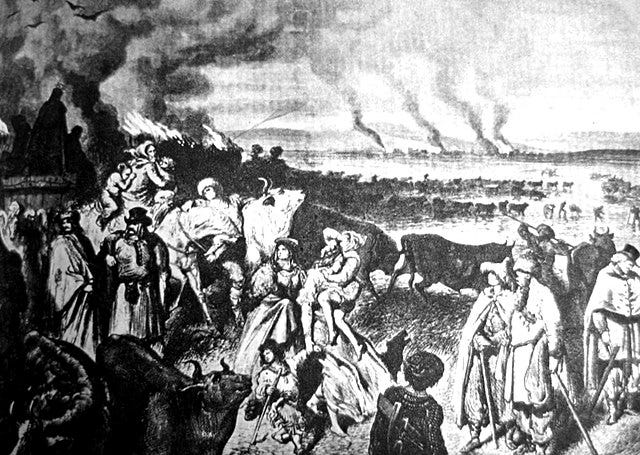

The advent of “coolie” labor

The sovereign interest in both identifying individuals and controlling their movement across borders was largely set into motion when the British brought a formal end to slavery in its colonies in 1838.[9] Radhika Mongia describes the British abolition of slavery as “perhaps the most significant legal transformation of labor relations, and hence the terms of contract, in the nineteenth century.”[10] This is because British colonies immediately began to shift to a system of Indian indentured labor, starting with Mauritius and followed soon thereafter by the Caribbean.[11] In China, the term used for a class of unskilled laborers at that time was “ku-li” (苦力), the verb “ku” meaning to be hired out. As white plantation owners throughout the Caribbean and South America found that their freed African slaves no longer wished to work for them, they began to import “coolie” laborers instead.[12]

The Industrial Revolution, which also started in the United Kingdom in 1750, was followed by migration from rural to urban centers, population growth and with that, a dramatic increase in business transactions between individuals who did not know one another. This had ramifications for the Western banking system. In the pre-modern era, Western and Central European banks were owned by consortia of families across major cities, and they could extend one another credit based on trust, honor, and familiarity with one another’s handwriting.[13] But now, large swaths of the world’s economy were constantly on the move:

“Improved transportation made the transfer of goods and people cost-effective, giving a boost to colonization and imperialism. Colonial powers could extract raw material from their colonies, have it processed in the factories and mills of the mother country, and returned for sale to the closed market of the colony. Just such a mechanism, which limited the colonies from creating their own manufacturing base, was one of the major economic causes of the American Revolution. The factory system created needs in the form of personal identification. Workers needed authorization to gain admittance to the mines or factories, and travelers needed evidence that they had paid for their methods of passage.”[14]

Modern warfare and urban crime

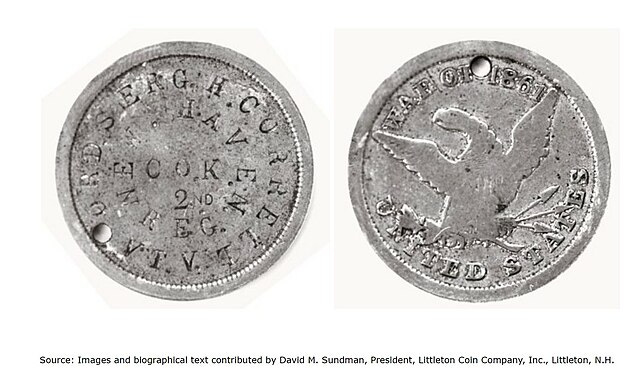

The 19th century also saw more modern methods of warfare, with large-scale conscripted armies and battles fought far from home. This gave rise to a need to identify anonymous strangers, including dead ones. In the U.S. Civil War (1861-1865), Union soldiers pinned their names and addresses into their uniforms or scratched them onto the backs of their belt buckles, so that their bodies could be identified on the battlefield and returned to their families for proper burial.[15] Harpers Weekly began advertising Soldier’s Pins, which could be ordered through the mail and could be inscribed with personal details, and vendors who followed troop movements offered personalized disks for sale prior to major battles.[16] Still, it would be several more decades before the U.S. Army adopted what are now known as “dog tags.”

Urbanization brought with it a rise in urban crime—to French authorities, a veritable “epidemic” of crime—with a dramatic increase in recidivism. According to the French Interior Ministry, the proportion of récidivistes among those arrested for crime rose from 28 percent in 1850 to 50 percent in 1881.[17] There appeared to now be a permanent criminal underclass of rural poor who moved to the city following bad harvests and would return to Paris no matter how many times they were expelled. Americans were dealing with a slightly different criminal phenomenon they called the “confidence man,” someone who could abuse the trust of strangers, swindle them, and then move on to the next city, exactly what de Tocqueville had noticed could happen in 1833.[18] But what were a person’s immutable characteristics, that were not likely to change with the person’s age and could not be easily disguised, such that repeat offenders could be reliably identified?

The Bertillon method and how it led to phrenology

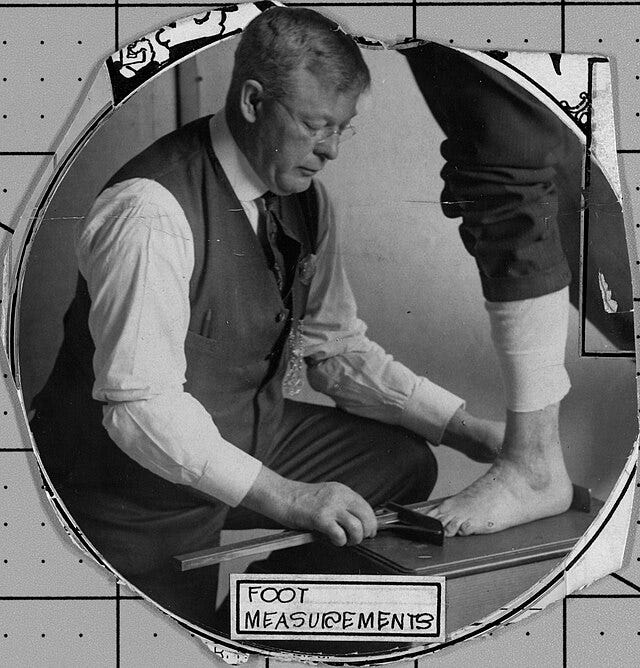

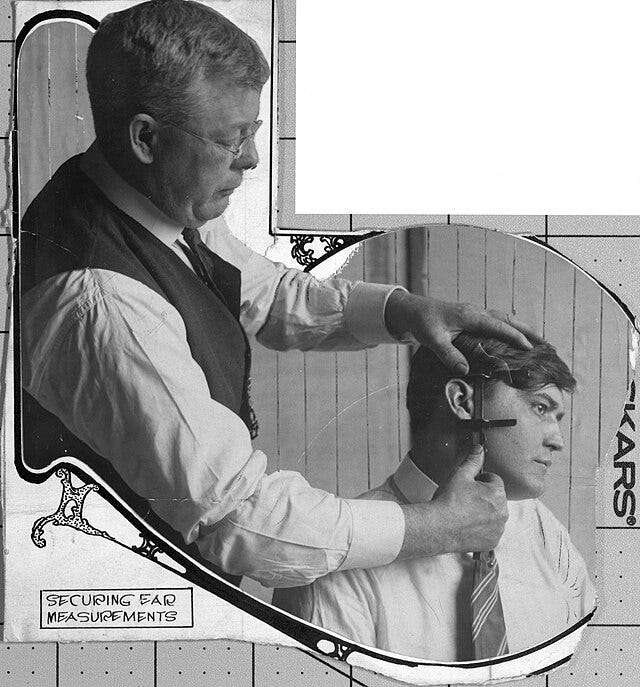

The problem of how to identify récidivistes in France was taken up by police official Alphonse Bertillon, who, being the son of a demographer and anthropologist, pioneered the use of eleven different anthropometric measurements of criminal suspects: height, head length, head breadth, arm span, sitting height, left middle finger length, left little finger length, left foot length, left forearm length, right ear length, and cheek width. He also developed extensive and precise guidelines for classifying eye color, lips, and especially ear types.

These were all recorded on special identity cards developed by Bertillon.[19] As the idea caught on, the Bertillonage method was translated into several languages and spread across police departments and prisons, instituting anthropomorphic identification in the United States and Canada in 1887, Argentina in 1891, colonial Bengal in 1893, and Great Britain in 1894. In 1898, the International Anti-Anarchist Conference in Rome embraced Bertillonage as a standardized identification system to be used across Europe for tracking international terrorists and other radicals.[20]

Some American and British institutions adopted variants of Bertillonage, but many of them preferred photography. The first reported “rogues’ gallery” featuring photographs of habitual criminals was utilized by the New York Police Department (NYPD) in 1858, a practice that had spread to London by 1870; the British Prevention of Crimes Act added photographs to the Register of Habitual Criminals.[21]

But then Bertillonage began to take a different direction, about which Bertillon himself expressed reservations. Some of his methodology evolved into a field that came to be known as “criminal anthropology,” less focused on simply identifying an individual, or “using the criminal body as a link to a criminal record,” and instead attempting to “read[] criminality directly from the body.”[22] Nineteenth-century anthropology, from which “criminal anthropology” emerged thanks to Bertillon, was in general “most concerned with ‘scientific’ observations of ‘savages’ and people of ‘other’ races.”[23] It was one of many fields of knowledge by which white Westerners were beginning to more formally justify their colonization, enslavement and continuing subjugation of the non-Western world. As I discussed in this post:

by the mid-19th century, Western thought had gradually drifted away from the notion that the West could somehow “civilize” indigenous people by conquering them and/or converting them to Christianity and had now hardened into the idea that certain races of people—in fact, all but one race—were simply irredeemable and not suited to republican government. Other “scientific” pursuits of the early 19th century, such as the French intelligence practice of statistique, or the sociological practice of observation,[24] now became married up with the idea that people behaved the way they did because of innate, biological characteristics, rather than prehistoric accidents of geography—the very Erroneous Assumption that I discussed in my review of Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel:

In the area of “criminal anthropology,” a new generation of scientists began exploring whether habitual criminals had different skull shapes, or tended to be more naturally underweight, compared to the mainstream population. They ultimately were not successful at finding “a reliable physical indicator of criminality,” but the larger scientific endeavor of phrenology, or trying to predict mental traits by examining bumps on the skull, was becoming quite fashionable in the late 19th century. The English used phrenology, for example, to argue that the Irish represented a lower evolutionary form of human.

The new thinking about the interplay between the individual, geography and culture was not only that people from certain lands shared immutable biological traits, but that those people belonged on that land. This is why we saw, as in the instance of U.S. deliberations over whether to acquire the island of Santo Domingo between 1869 and 1870, U.S. senators opining “that white racial limitations, fixed by nature and dictated along the lines of climate separating the temperate and tropical zones, made Santo Domingo unsuitable for settlement by people of ‘Germanic blood.’”[25] It was why, in 1918, the first generation of photographic imagery intelligence specialists mused over whether the French had a “racial advantage” in this field over Americans.[26] Various ethno-religious-linguistic groupings of people who “belonged” on a particular parcel of land began to be thought of by Europeans as “nations,” with the term “nationalism” coming to signify the belief that a person’s primary loyalty should be with his or her respective national group.

Passports as a mechanism for border control

The overlap between the concept of a nation and the concept of a race is how nationality eventually came to be seen as a (largely) immutable characteristic, and with it, the passport as a document that both authorized movement and validated a person’s identity.

At the height of the Industrial Revolution, Europe at first placed such an economic premium on the free movement of labor that, in France as late as the 1860s, the concept of “foreigner” simply did not exist in the same way that it would by the turn of the century.[27] In 1867, the North German Confederation moved to “decriminalize” travel and promote free movement within its own borders.[28]

The pre-Civil War United States likewise remained open to free movement, at least with regard to white people, with individual U.S. states largely left to regulate immigration within their own boundaries. It was not until 1848 that the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the Passenger Cases that it was unconstitutional for U.S. states to impose a “head tax” on alien passengers arriving in their ports, as this interfered with the federal government’s prerogative of regulating foreign commerce.[29] It then took until 1856 for the U.S. Congress to assert the exclusive right to issue passports; until then, states and even municipalities were free to distribute them.[30]

In France, the shift in the later 19th century from inclusiveness to xenophobia and nationalism was the Third Republic’s perceived need, particularly in the wake of France’s defeat in the Franco-Prussian war, to impose military service obligations on all French nationals, from which the large number of foreigners living and working on French soil were generally exempt. Because they were exempt, those who were subject to the military service obligation began complaining that foreign workers had unfair advantages in the labor market. The political debate eventually culminated in a law of October 2, 1888, extending the Bertillonage method of identifying recidivist criminals to the entire resident foreign population of France. This was followed by the Law Concerning the Sojourn of Foreigners in France and the Protection of National Labor of August 8, 1893, which required all foreigners to “register” if they wished to earn income in France. The foreigners were required to produce a valid piece of identification, such as a birth certificate, or some other form of identification that could be validated by their nation’s consular officials.[31]

As early as 1886 the Deuxieme Bureau’s Statistical Section was separately pursuing means of identifying foreigners using census data, for counterespionage purposes. Amid the growing paranoia about German espionage, which would eventually culminate in the infamous Dreyfus Affair, that same year French War Minister Georges Boulanger charged the military’s police apparatus, the gendarmerie, with “the pursuit and arrest of spies.”[32]

These two ideas converged over the next several months into two national lists called Carnets A and B:

“Carnet A identified foreign males of military age living in France, while Carnet B listed anyone, French or foreign, suspected of possible espionage, and therefore deemed a threat to French national security. As described by an instruction manual, the actual carnets were ‘formed of pliable folios, easy to detach, in order to follow individuals in all of their movements.’ The small booklet would note the suspect’s name, nationality, date and place of birth, current address, profession, and physical description. The main part of the carnet was composed of a list of the various actions that made the individual suspect.”[33]

At the Deuxieme Bureau, Colonel Sandherr began liaising with the Interior Ministry, which oversaw the civilian police, and despite competition between the two ministries as to who was in charge of counterespionage, the project continued, and Carnets A and B were maintained up until World War I. Sandherr additionally solicited help from a variety of agents at other ministries, such that, “in the years that followed, customs agents, hunters, forest guards, as well as agents of the railroad companies, the police, and the gendarmerie watched the borders, all reporting back to the Statistical Section on their findings regarding France’s external and internal safety.”[34]

In Germany, the concerns leading to nationality-based identification and passport controls were more strictly limited to labor; specifically, Russian and Polish labor migrating into Prussia from the east.

Interestingly, these passport and visa requirements were initially imposed in 1879 on those coming from Russia because of a purported plague that had broken out there; visa applicants were required to demonstrate that they had not been in any of the contaminated areas during the preceding 20 days. However, within a few months, this particular requirement was dropped, indicating that the real concern was not for public health, but the “Polonization” of Prussia through the importation of too many foreign agricultural workers. In 1885, Otto von Bismarck ordered the expulsion of 40,000 Polish workers. German sociologist Max Weber called for the “absolute exclusion of the Russian-Polish workers from the German east,” or else Germany would be “threatened by a Slavic flood that would entail a cultural retrogression of several epochs.” Weber saw agricultural employers essentially using Polish migrant labor as a “means of struggle in the anticipated class struggle in this area, directed against the growing self-consciousness of the workers.”[35]

The Chinese immigration “problem” and why we all have terrible passport photos now

A similar dynamic was taking hold in California in the 1870s and 1880s. For a period of over three decades following the California’s acquisition by the United States in the Mexican-American War,

“the Chinaman was welcomed, praised, and considered almost indispensable; for in those days race antipathy was subordinated to industrial necessity, and in a heterogeneous community where every Caucasian expected to be a miner or a speculator, the reticent, industrious, adaptable Chinese could find room and something more than toleration. They were highly valued as general laborers and cooks; the restaurants established by them in San Francisco and in the mines were well kept and extensively patronized; they took to pieces the old vessels that lay abandoned in the channel of the Golden Gate; they cleared and drained the rich tule lands, which the white miners were too busy to undertake. Governor McDougal recommended in 1852 a system of land grants to induce the further immigration and settlement of the Chinese—’one of the most worthy of our newly adopted citizens.’”[36]

Under the bilateral Burlingame Treaty of 1868, (which I last discussed here):

the United States agreed to allow Chinese “coolie” laborers to immigrate freely to the United States, albeit without any right to become naturalized U.S. citizens, just as China allowed Americans access to China.[37] But then, labor conditions changed. By 1880, this treaty had already been replaced with one that allowed the United States to limit the right of entry to Chinese whenever such immigration “affect[ed] or threaten[ed] to affect” American interests. By 1882, the U.S. Congress had adopted the first of the Chinese Exclusion Acts. The reason was the same as in Germany: resistance from white laborers, including a wide variety of Irish and European immigrants who, unlike the Chinese, had been able to naturalize as U.S. citizens and now wielded political power, aligning themselves with Southern Democrats who dominated California politics at that time.[38]

Nonetheless, because the 1882 Exclusion Act only barred incoming laborers, the Chinese who had already immigrated legally were allowed to remain in the United States as well as reenter if they left. However, this was subject to compliance with an elaborate system of certifications and identity verification. A Chinese laborer in the United States wishing to return to China had to first obtain a “return certificate” from the collector of the port prior to departing. Upon arrival in China, they were then required to obtain from the Chinese government a “Canton” or “Section Six” certificate (named after the relevant section of the Chinese Exclusion Act). In 1884, additional documentary requirements were added: now the “Section Six” certificate had to additionally be factually verified and a visa issued by a U.S. consular officer at the port of departure in China.[39]

To California politicians, this still was not enough. Within four years, California U.S. Congressman Thomas Geary successfully sponsored a law that now required all Chinese to obtain a “certificate stating minute particulars concerning themselves and must supply photographs at a cost of three dollars each.”[40] The requirement was to be implemented by the U.S. Treasury Department. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association in San Francisco (also known as “the Six Companies”) believed the law to be unconstitutional and advised the Chinese not to comply, with the Chinese government also registering its complaints through diplomatic channels.

The following year, as backlash to the Geary Act grew, Congressman McCreary of Kentucky pointed out that only 13,242 out of 106,668 had registered and sought a softening of the law’s more stringent provisions. However, Geary and Senator White, also from California, insisted that the registration law with photographs was necessary because individual Chinese were otherwise impossible to identify.[41]

Thus, the registration requirements remained in effect, even though they continued to be extremely difficult to enforce in practice:

Chinese cunning and duplicity were more than matched by American greed and corruption; sheriffs, court commissioners, and United States marshals and deputies, were known to be in collusion with Chinese agents on the borders and money seemed to smooth the way even at the ports of San Francisco and New York. The law permitted any person to lodge complaint before a Commissioner; wholesale arrests of Chinese persons became notorious; prisoners were in jail at the expense of the Government, marshals receiving two dollars a day; and the salaries of attorneys, Chinese inspectors and interpreters went steadily on…

The pressure at the borders and at illegal ports of entry was also increasing. The Chinese soon learned that if they attempted to enter at the appointed stations their papers might be taken away and there would be no appeal except to the Treasury Department. Certificates were precious, negotiable property….But if the Chinaman were arrested at the border he must be brought before a court commissioner and had an appeal to the higher courts.

The Treasury officials complained not only of the law’s defects but of the difficulty of enforcement due to evasion and frauds practiced by Chinese of all classes—unlawful entrance at the borders, transference of certificates, laborers posing as members of the exempt classes, and worst of all, younger Chinese claiming to be native-born citizens. It was even asserted that the wealthy Chinese were in collusion with governmental inspectors and interpreters to bring in laborers.”[42]

The corruption problem extended as well to U.S. consular officials in China who issued visas; as I noted in my previous post on extraterritorial jurisdiction, a local consular official representing the U.S. overseas was “sometimes a grossly unqualified and/or corrupt individual who gained the position via political appointment and would carry out serious miscarriages of justice while personally enriching himself by charging fees.”[43]

There were similar challenges in Canada, where the Canadian government had already tried imposing a “head tax” on Chinese migrants and had entered into a “gentleman’s agreement” with Japan, pursuant to which Japan would issue passports to only 400 emigrants annually (using the passport “less as a document of identity and more as what we now know as a quota system for visas.”)[44] An underlying problem was that there still was no reliable, fraud-resistant and scalable technology for verifying personal identity. At some point U.S. authorities tried to utilize some sort of Bertillon-inspired method of identification to enforce the Chinese Exclusion Laws, but they had abandoned the effort by 1906.[45] By then, Bertillonage, rather than having become the international standard, had been watered down and too often implemented sloppily, resulting in an “international patchwork of incompatible anthropomorphic systems” that eventually undermined the reputation of Bertillon’s original method.[46]

The Canadian Hindu crisis and the birth of the administrative state

Moreover, whatever Canada was able to accomplish to limit Chinese and Japanese immigration became exponentially more complicated when it came to Hindus and Sikh laborers, who, like white Canadians, were all part of a single British Empire. I explained the phenomenon of early 20th-century Hindu and Sikh migration to the American Northwest, and the animosity that developed towards them from white laborers in the lumber yards, in this post:

The same racial tensions between Indian and white laborers were vexing Canadian officials in British Columbia. Accordingly, in 1907, Canadian Prime Minister Wilfried Laurier proposed to the Colonial Office in London and the Government of India a passport-based quota system similar to that which Canada had worked out in its “gentleman’s agreement” with Japan. This, however, was a non-starter for the Viceroy of India, who wrote back that such restrictions would be impermissible under the Indian Emigration Act XXI of 1883, adding, “In present state of public feeling in India we consider legislation of this kind to be particularly inadvisable.” Here, the Viceroy was likely alluding to the agitation of Indian laborers in South Africa, as well as the Indian movement towards self-rule at home, for whom freedom of emigration was closely tied to their other anti-colonial demands.[47]

Following the race riots of 1907 that were instigated by the Anti-Asiatic League (also discussed in my above post), Canadian and British authorities decided to maximize their knowledge of every single aspect of the movement of Indians to Canada, including infiltrating the Anti-Asiatic League with a secret agent, obtaining copious amounts of data on every ship that sailed out of Hong Kong, including “ethnographies of the immigrants themselves…to understand their motivations,” and secret consultations in London between the Canadian Deputy Minister for Labor with colonial authorities.[48]

The conundrum this group of Canadian, UK and Indian colonial authorities faced was that they could not outright ban Indian migrants on the basis of race without undercutting the very foundation and legitimacy of the British Empire, which “had come to rest crucially on the definition of the term British subject.”[49] The British Empire, on which the sun at that time purportedly never set, consisted of multiple races, ethnic groups, even nations, and the Government of India needed to cling to the principle of “complete freedom for all British subjects to transfer themselves from one part of His Majesty’s dominions to another.”[50] This left the Empire’s white governing authorities at a loss as to “how to distinguish between British subjects, members of a single, expansionist state, without calling the entire edifice of the empire into question. It was a sense of empire and not of a territorially circumscribed nation that was paramount here.”[51]

The United States, by contrast, did not face this conundrum at all. In fact, when ethnic Chinese tried to enter the United States who had already acquired citizenship in Canada or Mexico, U.S. authorities made clear to them that their exclusion was based on “racial and moral grounds” rather than whether they were subjects of the Emperor of China.[52]

What the Canadians eventually came up with was an elaborate system of excluding virtually all Indians from Canada that appeared racially neutral, but that allowed for administrative discretion that would then always be exercised in favor of white migrants. What authorities had learned from their exhaustive investigative efforts was that Indians could not travel directly from India to Canada, so most of them went through Hong Kong first, or had actually worked in another country for some time before moving onward to Canada. Thus, on January 8, 1909, the province of British Columbia passed an Order-in-Council stating that “immigrants shall be prohibited landing [in Canada], unless they come from [their] country of birth or citizenship by continuous journal, and on through tickets purchased before starting.” When this regulation resulted in the refusal of entry to two well-educated and apparently desirable men from France and Russia who had arrived in Vancouver from Japan, the regulation was then re-worded from “shall be prohibited” to “may be prohibited.” This enabled Canadian immigration officers to exercise discretion and thereby permit white immigrants to enter while blocking Indians.

As Mongia observes,

“[t]he introduction of caveats and the necessary bureaucratic discretion they entail has become an increasingly important part of current legal regimes, particularly in domains such as migration law. Now an entire branch of law, called administrative law, it serves as a way of incorporating exceptions in and to the rule and shielding decisions on such exceptions from judicial review. As with several other contemporaneous legal measures undertaken by different white-settler states, the continuous journey regulation embodied the ‘open secret’ of racial thinking in the law: without knowledge of the very particular contexts, their racist rationale was obscured.”[53]

This was a great leap forward for the administrative machinery of the modern nation state; “[i]t was not just that the state was propelled into action by racist ideologies or that race structured state policy, but that such moments functioned as catalysts that aided the development of a specifically modern regime of state power."[54]

Again, the state was still lacking several technologies it would need both to identify individuals and track their movements, as through travel documents, but when those technologies did become available, there were now more sophisticated processes that could leverage them. We will get into the technologies in the next post. They include photography, fingerprinting, library science, and, of all things, the filing cabinet.

(cont’d)

[1] National Intelligence University Catalog for Academy Year 2024-25, at 130, available at https://www.ni-u.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/08/NIU-Catalog-24-25_08272024.pdf (viewed February 17, 2025).

[2] Id. at 100.

[3] For an overview of Arabic naming conventions and the difficulty Western engineers encounter when attempting to conduct data analysis on large numbers of individuals who follow these conventions, see, e.g., Niccolò Dalmasso et al., “Feature Engineering for Entity Resolution with Arabic Names: Improving Estimates of Observed Casualties in the Syrian Civil War,” 1st Workshop on Artificial Intelligence for Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Response (NeurIPS 2019), Vancouver, Canada, available at https://www.cmu.edu/chrs/publications/pdf/ai_for_hadr_neurips_2019.pdf (viewed February 18, 2025).

[4] See, e.g., Diaa Hadid, “The reason why there are so many Jan. 1 birthdays in Pakistan and Afghanistan,” National Public Radio (NPR), heard on Morning Edition, January 1, 2024, available at https://www.npr.org/2024/01/01/1222380438/the-reason-why-there-are-many-jan-1-birthdays-in-pakistan-and-afghanistan (viewed February 18, 2025).

[5] Ashkenazi Jews, for the most part, did not have fixed family names until the 19th century. There are a few families with a tradition of descent from King David who can trace their last names to the Babylonian Exile f 580 BCE. Jews in Italy, Spain and Portugal began to adopt hereditary family names between the 10th and 13th centuries. However, some adopted aliases during the Spanish Inquisition, and others who fled Spain took refuge in the Ottoman Empire, which never required Jews to adopt fixed surnames. In 1787, Habsburg Emperor Joseph II was the first ruler to require the Jews to adopt fixed surnames, followed by Russian Czar Alexander I in 1804 and Napoleon in 1808. Because Russia was collecting names for the military draft, many Russian Jews used a variety of aliases and subterfuges, such as registering brothers with different surnames. Thus, fixed surnames for Jews were not solidified until the early 20th century. Sallyan Amdur Sack, “Family Names,” in Sallyann Amdur Sack and Gary Mokotoff, eds., Avotaynu Guide to Jewish Genealogy (Avotaynu: Bergenfield, New Jersey, 2004), at 30-34.

[6] See, e.g., “Religious Medallions,” Jamestown Rediscovery, at https://historicjamestowne.org/collections/artifacts/material/religious-medallions/?srsltid=AfmBOopc-pD9zg620gWqg79kZtYJi0CSL28xvWBFBf-zQh7HYnyAt8Pc (viewed February 18, 2025); David Collins, “A Catholic at Jamestown? A Historian Reflects,” America: Jesuit Review, July 29, 2015, available at https://www.americamagazine.org/content/all-things/catholic-jamestown-historian-reflects (viewed February 18, 2025).

[7] Indiana State Library, “A Not-so-Brief History of the United States Passport,” September 5, 2024, available at https://blog.library.in.gov/a-not-so-brief-history-of-the-united-states-passport/ (viewed February 21, 2024).

[8] Quoted in Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Harvard University Press, 2001), at 17.

[9] Radhika Mongia, Indian Migration and Empire: A Colonial Genealogy of the Modern State (Duke University Press, 2018), at 24-5.

[10] Radhika Mongia, Indian Migration and Empire: A Colonial Genealogy of the Modern State (Duke University Press, 2018), at 23.

[11] Radhika Mongia, Indian Migration and Empire: A Colonial Genealogy of the Modern State (Duke University Press, 2018), at 25.

[12] Mary Roberts Coolidge, Chinese Immigration (New York, Holt and Company, 1909), at 42-45.

[13] David J. Haas, Personal Identification: Modern Development and Security Implications (CWC Press, 2d Ed., 2024), at 23-24.

[14] David J. Haas, Personal Identification: Modern Development and Security Implications (CWC Press, 2d Ed., 2024), at 24.

[15] David J. Haas, Personal Identification: Modern Development and Security Implications (CWC Press, 2d Ed., 2024), at 26.

[16] David J. Haas, Personal Identification: Modern Development and Security Implications (CWC Press, 2d Ed., 2024), at 42-43.

[17] Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Harvard University Press, 2001), at 32-48.

[18] Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Harvard University Press, 2001), at 20.

[19] Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Harvard University Press, 2001), at 32-48.

[20] Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Harvard University Press, 2001), at 51-52.

[21] Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Harvard University Press, 2001), at 20.

[22] Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Harvard University Press, 2001), at 57.

[23] Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Harvard University Press, 2001), at 57.

[24] Deborah Susan Bauer, Marianne is Watching: Knowledge, Secrecy, Intelligence and the Origins of the French Surveillance State (1870-1914), Ph.D. thesis, UCLA (2013), at 19, available at https://escholarship.org/content/qt7rt4z6js/qt7rt4z6js.pdf (viewed January 10, 2025).

[25] Eric T.L. Love, Race over Empire, Racism and U.S. Imperialism, 1865-1900 (North Carolina Press, 2004), at 55. In his correspondence with Grant, Schurz explained his opposition to the treaty as follows: “in short, acquisition and possession of such tropical countries with indigestible, unassimilable populations would be highly obnoxious to the nature of our republican system of government; it would greatly aggravate the racial problems we already had to contend with; those tropical islands would, owing to their climatic conditions, never be predominantly settled by people of Germanic blood…this federative republic could not without dangerously vitiating its principles, undertake to govern them by force, while the populations inhabiting them could not be trusted with a share of governing our country.” Id. at 53-54 (quoting Schurz’s biography Reminiscences).

[26] Mark Stout, World War I and the Foundations of American Intelligence (University Press of Kansas, 2023), 150-52.

[27] Deborah Susan Bauer, Marianne is Watching: Knowledge, Secrecy, Intelligence and the Origins of the French Surveillance State (1870-1914), Ph.D. thesis, UCLA (2013), at 234 (discussing Gérard Noiriel’s French Melting Pot).

[28] John Torpey, The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State (Cambridge University Press, 1st Ed. 1999), at 117.

[29] Passenger Cases, 48 U.S. 283 (1848).

[30] [30] John Torpey, The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State (Cambridge University Press, 1st Ed. 1999), at 116.

[31] John Torpey, The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State (Cambridge University Press, 1st Ed. 1999), at 130-32.

[32] Deborah Susan Bauer, Marianne is Watching: Knowledge, Secrecy, Intelligence and the Origins of the French Surveillance State (1870-1914), Ph.D. thesis, UCLA (2013), at 226, available at https://escholarship.org/content/qt7rt4z6js/qt7rt4z6js.pdf (viewed February 21, 2025).

[33] Deborah Susan Bauer, Marianne is Watching: Knowledge, Secrecy, Intelligence and the Origins of the French Surveillance State (1870-1914), Ph.D. thesis, UCLA (2013), at 235.

[34] Deborah Susan Bauer, Marianne is Watching: Knowledge, Secrecy, Intelligence and the Origins of the French Surveillance State (1870-1914), Ph.D. thesis, UCLA (2013), at 237.

[35] John Torpey, The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State (Cambridge University Press, 1st Ed. 1999), at 133-34.

[36] Mary Roberts Coolidge, Chinese Immigration (New York, Holt and Company, 1909), at 21-22.

[37] Mary Roberts Coolidge, Chinese Immigration (New York, Holt and Company, 1909), at 76-77.

[38] Mary Roberts Coolidge, Chinese Immigration (New York, Holt and Company, 1909), at 40, 81.

[39] John Torpey, The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State (Cambridge University Press, 1st Ed. 1999), at 120-21.

[40] Mary Roberts Coolidge, Chinese Immigration (New York, Holt and Company, 1909), at 213-14.

[41] Mary Roberts Coolidge, Chinese Immigration (New York, Holt and Company, 1909), at 227, 231.

[42] Mary Roberts Coolidge, Chinese Immigration (New York, Holt and Company, 1909), at 238-39.

[43] DeB. Randoph Keim, Examination on accounts of consular officers of the United States, exec doc. No 317, 42nd Congr. 2nd Session, 27 May 1872 (hereinafter “Keim Report”), available at file:///Users/laraballard/Downloads/SERIALSET-01520_00_00-033-0317-0000.pdf (viewed September 4, 2024), at 19, 184.

[44] Radhika Mongia, Indian Migration and Empire: A Colonial Genealogy of the Modern State (Duke University Press, 2018), at 120.

[45] Mary Roberts Coolidge, Chinese Immigration (New York, Holt and Company, 1909), at 306.

[46] Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Harvard University Press, 2001), at 52-53.

[47] Radhika Mongia, Indian Migration and Empire: A Colonial Genealogy of the Modern State (Duke University Press, 2018), at 120-21.

[48] Radhika Mongia, Indian Migration and Empire: A Colonial Genealogy of the Modern State (Duke University Press, 2018), at 122.

[49] Radhika Mongia, Indian Migration and Empire: A Colonial Genealogy of the Modern State (Duke University Press, 2018), at 126.

[50] Radhika Mongia, Indian Migration and Empire: A Colonial Genealogy of the Modern State (Duke University Press, 2018), at 131.

[51] Radhika Mongia, Indian Migration and Empire: A Colonial Genealogy of the Modern State (Duke University Press, 2018), at 127.

[52] Mary Roberts Coolidge, Chinese Immigration (New York, Holt and Company, 1909), at 295-96.

[53] Radhika Mongia, Indian Migration and Empire: A Colonial Genealogy of the Modern State (Duke University Press, 2018), at 124.

[54] Radhika Mongia, Indian Migration and Empire: A Colonial Genealogy of the Modern State (Duke University Press, 2018), at 122.