I incorporated a particularly large collection of maps, videos and photographs from Wikimedia Commons into my last post, which seemed appropos seeing as it was about geographic and image intelligence:

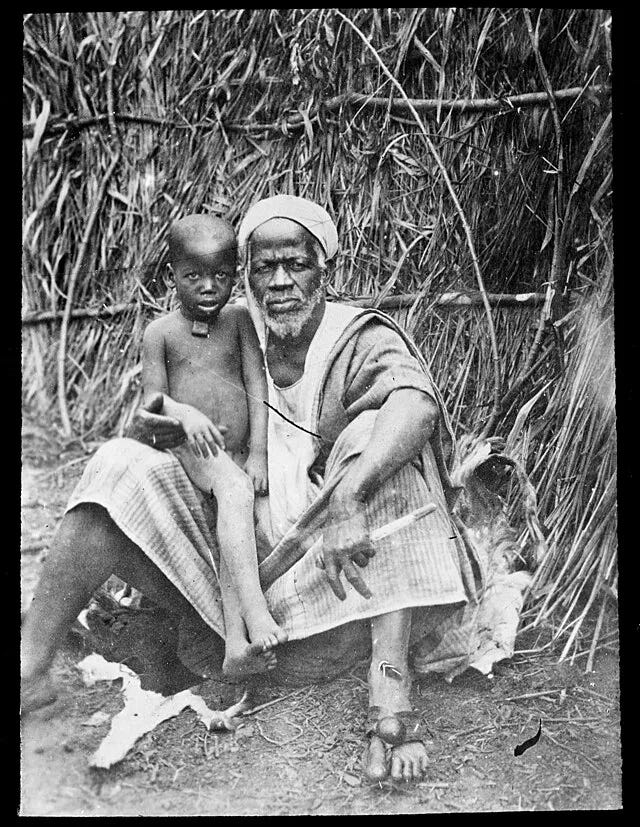

Most of the images I chose quite consciously, even if it wasn’t immediately evident to the reader why they were there. My wife said me afterwards, “I didn’t understand why you chose that photo of the Senegalese man and the boy.” I said, “It was because Brosselard took the photo.”

She said, “Well, I didn’t read the caption. It was in French.” To that I say (a) I’m trying to copy the captions and copyright restrictions exactly as they appear in Wikimedia Commons to keep copyright trolls off my case; and (b) if you really can’t read French well enough to get the gist of “Enfants -- Sénégal Palissades -- Sénégal Sénégal Portraits collectifs Appartient à l’ensemble documentaire : PhoVerre3 Couverture : Sénégal. Photogragher Brosselard-Faidherbe, Henri (1855-1893),” then by all means cut and paste it into Google Translate.

I included it because I thought it was somewhat redeeming on Brosselard’s part that, while he was out there with all his surveying equipment, drawing lines through West Africa to divvy it up between France and Portugal, he did at least see the humanity in the people he encountered. You can sometimes tell what a person thinks of another person by the way they photograph them. Brosselard is giving his subjects dignity. Contrast that with how some Americans photographed their Filipino subjects, from my post about the Philippines last month:

See what I mean? There are a lot of Brosselard photographs on Wikimedia Commons, and they all seem to have that same quality of his; go search for “Brosselard” there and you’ll see them. Thank you to the French-speaking person who uploaded them all for free, and please, feel free to continue captioning them in whatever language you like.

Anyway, I was particularly interested in what images I might find relating to the British advance into Palestine and the Battle of Gaza of November 1917. I ended up inserting four images into my post; this one was the last one.

I don’t know why I included it. I already had three images. I didn’t know anything about the cemetery, or really a lot more about the Third Battle of Gaza than what I posted. Maybe I was just in some sort of macabre mood.

At any rate, I woke up Monday morning after posting it, and I thought, “I wonder if that cemetery is still there.” I didn’t think it would be. After everything that’s happened in Gaza since 1917, much of it in the past 18 months or so, I thought, really, could somebody with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission have been maintaining a British War Cemetery on the Salah al-Din Road in Gaza City’s Tuffah district, all this time?

Well, remarkably, someone has, and off I went down another rabbit hole. Here’s the cemetery’s official web page:

Commonwealth Gaza War Cemetery

The cemetery is administered by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. The CWGC, according to its website, was was created and incorporated by Royal Charter on May 21, 1917, because “[a] vast number of bodies needed to be buried, yet there were many thousands more who lay undiscovered or who no longer had intact bodies that could ever be found. Even the authorities were not prepared for the practicalities of dealing with the dead: there was no formal process of ordering or recording burials, resulting in many isolated graves and small makeshift cemeteries with temporary markers.”

Today the CWGC is a multinational workforce of about 1300 employees—most of them gardeners and stone masons. They care for war graves at 23,000 locations in more than 150 countries and territories, “ensuring that all the Commonwealth men and women who died during both world wars are commemorated in a manner befitting their sacrifice.”

Here’s what the CWGC website says specifically about the Gaza War Cemetery:

“Gaza was bombarded by French warships in April 1915. At the end of March 1917, it was attacked and surrounded by the Egyptian Expeditionary Force in the First Battle of Gaza, but the attack was broken off when Turkish reinforcements appeared. The Second Battle of Gaza, 17-19 April, left the Turkish forces in possession and the Third Battle of Gaza, begun on 27 October, ended with the capture of the ruined and deserted city on 7 November 1917. Casualty Clearing Stations arrived later that month and General and Stationary hospitals in 1918.

“Some of the earliest burials were made by the troops that captured the city. About two-thirds of the total were brought into the cemetery from the battlefields after the Armistice. The remainder were made by medical units after the Third Battle of Gaza, or, in some cases, represent reburials from the battlefields by the troops who captured the city. Of the British Soldiers, the great majority belong to the 52nd (Lowland), the 53rd (Welsh), the 54th (East Anglian) and the 74th (Yeomanry) Divisions.

“During the Second World War, Gaza was an Australian hospital base, and the AIF Headquarters were posted there. Among the military hospitals in Gaza were 2/1st Australian General Hospital, 2/6th Australian General Hospital, 8th Australian Special Hospital, and from July 1943 until May 1945, 91 British General Hospital. There was a Royal Air Force aerodrome at Gaza, which was considerably developed from 1941 onwards.

“Gaza War Cemetery contains 3,217 Commonwealth burials of the First World War, 781 of them unidentified. Second World War burials number 210. There are also 30 post war burials and 234 war graves of other nationalities.”

Here’s another interesting fact: 42 of these gravesites are for Indian soldiers (use the Find War Dead feature on the website).

So, at least 42 Indians, colonized by Britain, serving in the 3rd Queen Alexandra’s Own Gurkha Rifles, the 101st Indian Grenadiers, the 23rd Sikh Pioneers, or one of several other units, died as part of the Egypt Expeditionary Force, helping Britain wrest control of Gaza away from the Ottoman Empire. Let that sink in for a minute.

And then, add this other interesting fact, again off the CWGC website: “Casualties within the Indian section of this cemetery were originally commemorated by a nameless memorial with their names added to a cemetery register. In 2000, their names were added to the memorial” (emphasis added).

If you want to see what it looks like, here’s a Gazan teenager giving an oddly chipper tour of the cemetery 6 years ago:

And here’s a much more extensive interview with Ibrahim Jaradah, whose family has been looking after the cemetery for over 100 years. This interview was conducted two years ago.

Ibrahim’s great-grandfather, Rabie Jaradah, started working for the predecessor to the CGWC in 1923 in Beershebah. During the 1948 formation of the state of Israel, his family was forced to flee to Gaza, where he was soon asked to take responsibility for the cemeteries. Rabie Jaradah regularly took his son, also named Ibrahim, on his rounds tending to the gardening of the cemetery when he was a schoolboy. Ibrahim brought along his son Essam, and the business has been passed down through the Jaradah family ever since (that story is here, on BBC News, from January 2023).

Of the current conflict, the senior Ibrahim Jaradah observed to the Sydney Morning Herald in October 2023, "This is where war always ends." Indeed.

As for the current condition of the cemetery, the CGWC website has this update as of January 28, 2025, suggesting that Ibrahim Jaradah is still out there tending to the gravesites.

“Current condition of cemeteries and types of damage

As a result of the ongoing conflict this cemetery has suffered extensive damage in the following areas:

Boundary walls, the staff house and base site and the Canadian Section. Approx 10% of the headstones in the site are damaged. Memorials with reported damage are the 54th (East Anglian) Division Memorial, the Hindu Section, Indian UN Memorial, the Turkish section and the Muslim section.”

The website additionally notes that the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) currently “advises against all travel to Gaza.”

Indeed.

Five of the caretakers of Gaza War Cemetery were released into Egypt in May 2024. Some immediate family members were allowed to leave. This was as the Rafah crossing was seized and sealed.

However, one staff member, thought to be Yacoub Ismaili, a fifty something year old gardener, with at least two decades service, chose to remain for family reasons. His current situation is not known.

There is a fascinating short doc about the work of the staff of Gaza War Cemetery on YouTube called, ‘The English Cemetery of Gaza - the Strange Neighbor’ (2018).