The United States, SIGINT, and World War I

The U.S. entry into World War I had an enormous and lasting impact on the development of the U.S. national security apparatus. For the next several weeks, I will be breaking down the immense amount of material in accordance with the modern intelligence collection disciplines, in addition to identity resolution and enforcement capacity, of which I took an inventory in this post:

I will start with Signals intelligence, or SIGINT:

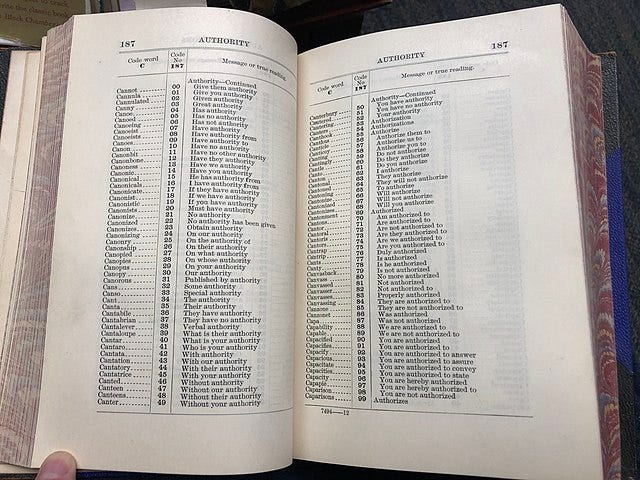

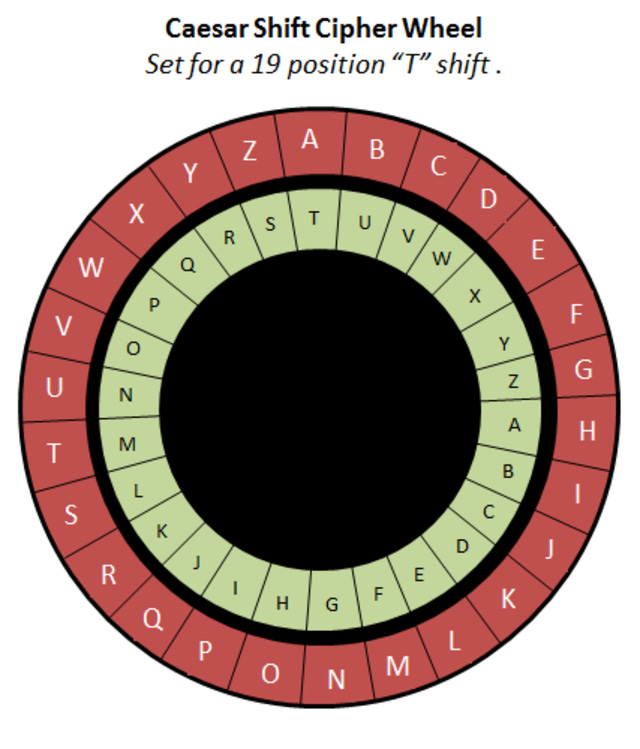

Signals intelligence (SIGINT) entails both the practical ability to intercept communications and the technical skill at decrypting them when necessary. The term “cryptology” includes both cryptography and cryptanalysis. Cryptography is the art of encrypting one’s own communications; cryptanalysis is the art of decrypting those of one’s enemies. Communications are typically encrypted either via codes or ciphers. A code replaces potentially thousands of words, phrases, or letters with code words or code numbers; e.g., “emplacing” becomes “3964.”

In a cipher, the basic unit is the letter; a cipher is more of a substitute alphabet, such that the letter “e” becomes “y” or “$.”

Encryption systems can combine elements of both codes and ciphers.[1]

In David Kahn’s magnum opus The Code Breakers, he describes the First World War as “the great turning point in the history of cryptology. Before, it was a small field; afterwards, it was big. Before, it was a science in its youth; afterwards, it had matured. The direct cause of this development was the enormous increase in radio communications.

“This heavy traffic meant that probably the richest source of intelligence flowed in these easily accessible channels. All that was necessary was to crack the protective sheath.”[2]

With the declaration of formal hostilities, the bored and frustrated State Department code clerk, Herbert O. Yardley, immediately began searching for a way to lend his burgeoning cryptologic talents to the war effort. As luck would have it, his path would soon cross with that of another who shared his frustrations: Major Ralph van Deman, who had returned to Washington from the Philippines in 1915, having learned quite a bit about Japanese espionage from a 1911 mapping mission into China. Van Deman found that the domestic U.S. military intelligence unit, unlike its formidable Philippines counterpart, had been relegated to a small section of the War College, where he found himself “the only officer…who had any training or experience in what we now designate as military intelligence.”[3]

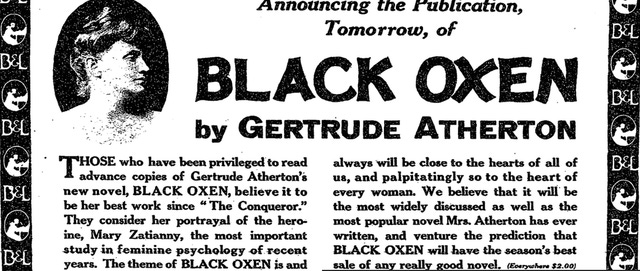

As Yardley was exploring his options, Van Deman was furiously lobbying the U.S. Army’s Chief of Staff, Hugh Scott, to create a military intelligence section within the General Staff. Scott not only rebuffed Van Deman’s request several times, he gave him strict orders to definitely not approach Secretary of War Newton D. Baker with the idea. So Van Deman took the idea to feminist novelist Gertrude Atherton, who had recently returned from having performed charity work on the Western Front with Le Bienêtre du Blessé, Société Franco-Américaine pour nos Combattants in France,[4] and she took the proposal to Baker on his behalf.[5]

Soon Van Deman was building a domestic Military Intelligence Section (later a Military Intelligence Division) based on a borrowed British organizational chart, with plans to centralize information from all federal agencies and engage in both espionage and counter-espionage. [6]

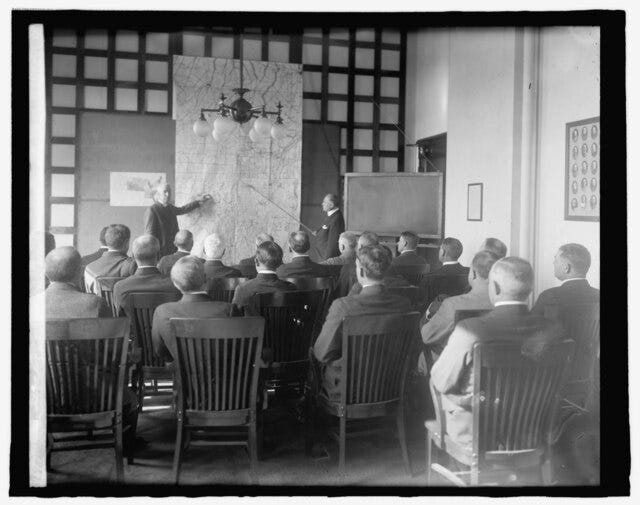

Van Deman began recruiting his fellow Philippines veterans, while Yardley was still casting about town for any Army or Navy contacts he could find. Yardley eventually found a colonel in the U.S. Army Signal Corps, which at the time consisted of only 55 officers and 1,570 enlisted men but whose mission in war was to provide the Army with all needed communications facilities and services (including intercept capabilities), photographic assistance and products, meteorologic information, and code compilation.[7] The colonel sent him to talk to Van Deman at the War College, where the 27-year-old Yardley successfully pitched Van Deman on the idea of training other cryptographers to support the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in France, earning himself an Army officer’s commission in the process.[8]

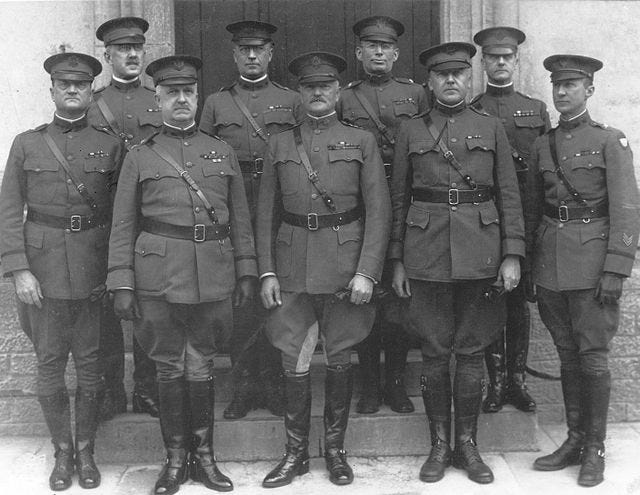

To command the AEF, President Wilson appointed General John J. “Black Jack” Pershing, who as a young officer had distinguished himself during the Spanish-American War in Cuba, and later in the Philippines, where he conducted a campaign against the Moros in 1903. Based on his service, he was rapidly promoted to colonel and then brigadier general by President Teddy Roosevelt, afterwards serving as governor of Moro Province until 1913. In 1916 Pershing had led a punitive expedition into Mexico to try to capture the revolutionary Pancho Villa, one outcome of which was that German spies in Mexico had been able to steal a copy of the U.S. War Department’s cryptographic code book.[9]

As the new head of the War Department Cryptographic Bureau, designated as MI-8 (Military Intelligence Division, Section No. 8), Yardley immediately sent cables to the United States’ new allies, asking them to send both examples of German military codes and ciphers and their solutions, and some skilled cryptographers who could instruct new students in Washington. He received the former but not the latter; cryptographic instructors purportedly could not be spared.[10] The British did, however, separately warn the War Department that its own cryptographic codes had been compromised and that the Germans were routinely intercepting all of its cablegrams.[11]

The British cryptographers were somewhat reluctant to offer much help even to their French allies, much less the United States. France in general was the only power prepared to wage a cryptographic war prior to the outbreak of hostilities. The French were also the earliest to capitalize broadly on the widespread military usage of radio communications, which were far easier to intercept than telegraphs due to their public and omnidirectional nature. Well prior to the war, Captain François Cartier, an engineer and graduate of the École Polytechnique, had solved German Army cryptograms that French radio stations had intercepted during their military maneuvers, and had formed a cryptanalytic bureau under his leadership by 1914.

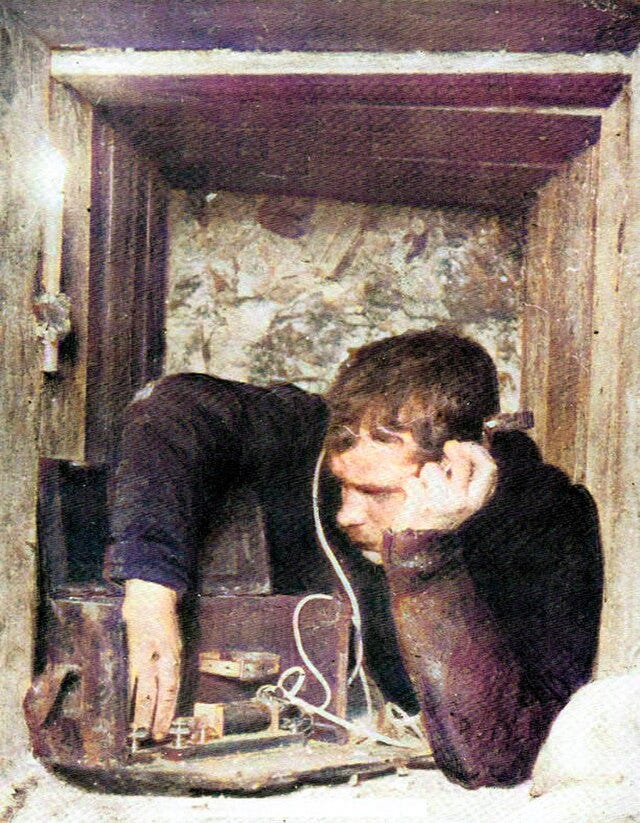

When the Germans crossed into France, the French quickly set up a more comprehensive national network of radio intercept stations, including one on the Eiffel Tower and another in a Métro (Trocadéro), which were connected by direct wire to the War Ministry, where now-Colonel Cartier’s section could receive German radiograms as quickly as the legitimate recipients.

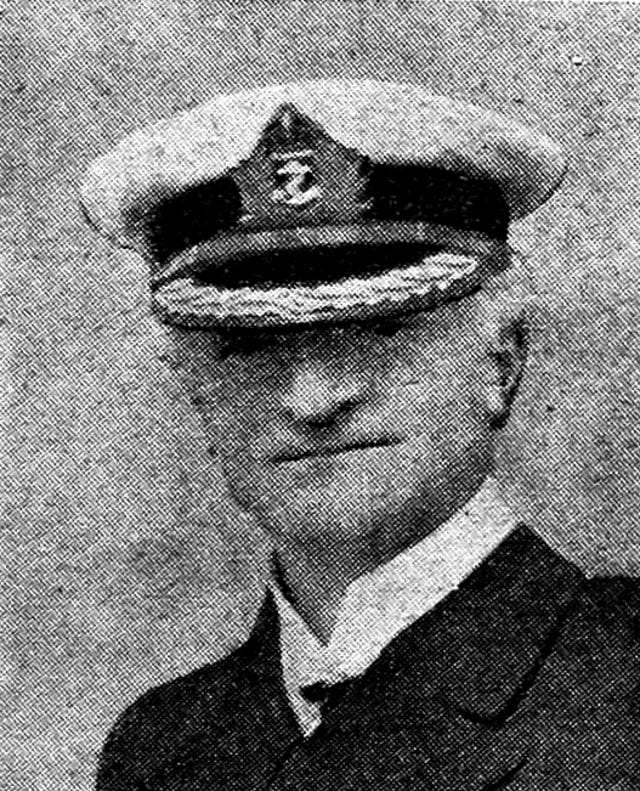

The greatest cryptanalyst of World War I was French Lieutenant Georges Painvin, who early in the war had reconstructed a German U-boat code. The French had radio posts near Marseilles that were able to intercept coded messages between the Germans and their waterfront spies regarding departing French ships, which naval cryptanalysts like Painvin could then decrypt in less than an hour and usually transmit the information back to the French ships in time to foil the U-boat attacks. The French sent many of their naval solutions to their British naval counterparts, but the head of “Room 40,” Captain Reginald “Blinker” Hall, was especially stingy in reciprocating.[12] The French also helped the separate British military cryptanalytic unit, known as M.I. 1(b), which only had four cryptanalysts at the beginning of the war but would have 84, including 30 women, by its end.[13]

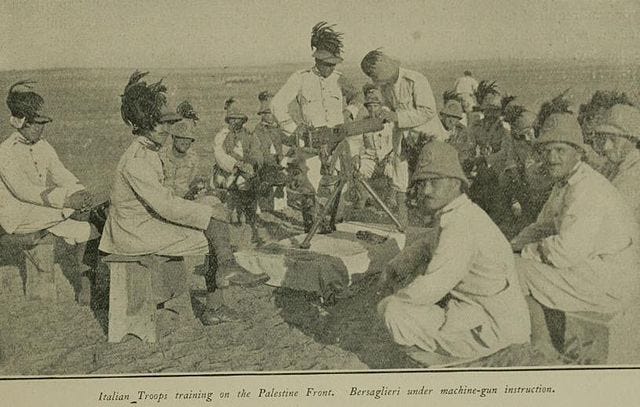

The Germans, in contrast to the French, had been lackadaisical about SIGINT generally, confident in their ability to overrun the French by sheer force of arms.[14] The Austrians and Italians were slightly more advanced, with the Italians having gained some valuable experience while fighting the Ottoman Empire over Libya in 1911, and after 1915, the Austrians over South Tyrol.[15]

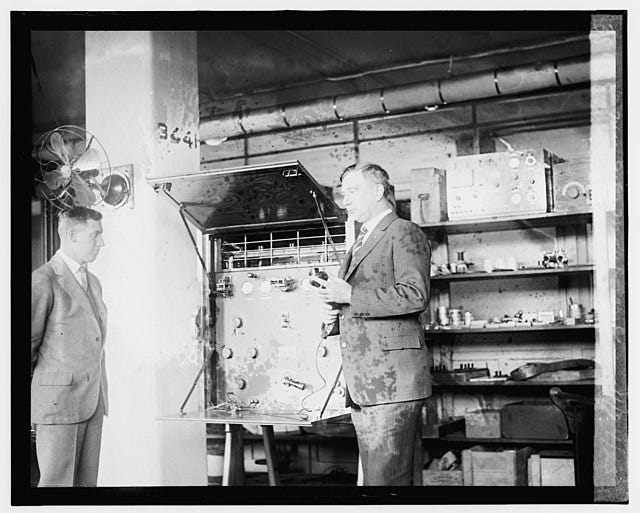

With no cryptology instructors to be spared from Europe, the U.S. Army turned to the private sector for solutions. The only private company in the United States studying cryptology at that time was on a 500-acre estate called Riverbank Laboratories in Geneva, Illinois, owned by an eccentric textile merchant named George Fayban. Riverbank maintained a Department of Genetics, which sought to improve the grains and livestock on its farm; and a Department of Ciphers, whose main purpose was to further Fayban’s quixotic obsession with proving that Francis Bacon had secretly authored all the plays of William Shakespeare. By 1917, the head of both departments was William Frederick Friedman, whom Fayban had hired as a geneticist but who had then become enraptured with cryptology around the same time he fell in love with a fellow cryptologist at Riverbank named Elizebeth Smith, whom he married that May. When the U.S. Army sent a class of officers to Riverbank in the fall of 1917 to learn cryptology, W.F. Friedman conducted most of the instruction, publishing a series of technical monographs. The Friedmans would go on to become the most famous husband-and-wife team in the history of cryptology.[16]

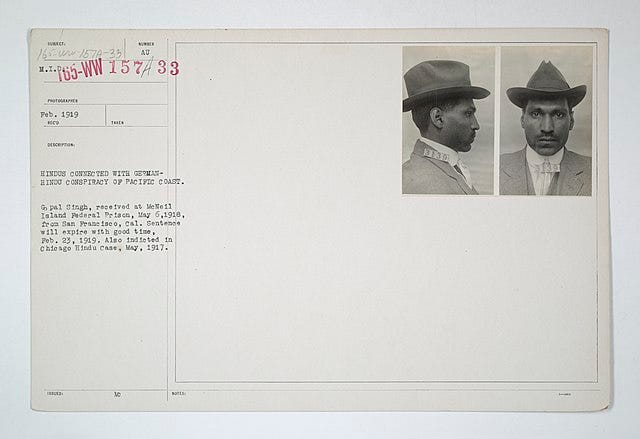

It was Riverbank Laboratories to whom the U.S. Justice Department appealed for help in its sprawling set of “Hindu conspiracy” trials that had been set into motion following the March 6, 1917, arrest in New York City of Berlin Ghadar Party member Chandra Kanta Chakravarty and his German contact, Ernest Sekunna. Among the Ghadar Party officials who had traveled to Berlin with Taraknath Das in 1914 was Heramba Lal (H.L.) Gupta, who had been assigned to work alongside German agents in Chicago to purchase arms in the United States and then organize a mission to Siam to recruit and train Indian revolutionaries.[17] The British and Canadians were helpful to U.S. prosecutors up to a point, as they were conducting their own conspiracy trials in Lahore and Singapore to address the immediate threat to the British Empire, but Justice Department officials had their own goals for the trials: to show a vast conspiracy that would prove that U.S. borders were far too porous and that something needed to be done about the large numbers of nefarious immigrants streaming across them.[18] Accordingly, the Americans could not rely on the British for all of their SIGINT needs. On March 10, 1917 U.S. authorities arrested H.L. Gupta in Chicago and decided to use the Chicago trial as a test case and a precedent for applying the conspiracy statute to the military expedition law.[19]

As part of that effort, they sent to Friedman a cablegram sent by Gupta to his German co-conspirators in Berlin, in the form of a seven-page typewritten letter, in which Gupta had stupidly opted to only encipher the important words, leaving plenty of “plaintext” from which Friedman could easily establish patterns and context, enabling him to decrypt the rest. Friedman went on to testify against the co-conspirators at the trial in Chicago,[20] at which Gupta was convicted on October 20, 1917; and again at the larger trial in San Francisco, which ran from November 20, 1917 until April 1918 and included 42 Indian and German co-defendants.[21]

Friedman’s work on the “Hindu conspiracy” trials appears to have attracted the attention of the British military cryptographic bureau, M.I. 1(b), who began sending him samples of text enciphered by a new cipher device they had invented for their troops in the field. The husband-and-wife Friedman team broke the code in less than three hours and promptly cabled the decrypted sample back to London, the first sentence of which read, “This cipher is absolutely undecipherable.” Needless to say, the new device was never adopted for Allied use.[22]

The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) were struggling with the same problem—how to create an encipherment device that was simple and convenient enough even for troops under fire to use for quick, tactical communications. Two Signal Corps officers who received their training at the Army War College and Riverbank under Yardley’s MI-8, Parker Hitt and Joseph Mauborgne, eventually developed a cylindrical encryption device, the M-94, that they then took to Europe when Hitt went to France with Pershing’s staff. The device and its improved variant, the M-138-A, continued to be used by the Army, Navy and State Department until the early 1940s.[23]

The AEF’s General Orders No. 8 of July 5, 1917, assigned “codes and ciphers” to the Signal Corps but gave “policy regarding preparation and issue of ciphers and trench codes” to its own Military Intelligence Division headed by Major Dennis E. Nolan, who quickly set about borrowing best practices from the British and the French. [24] This close collaboration between cryptographers and cryptanalysts resulted in two new AEF organizations: G.2 A.6, the Radio Intelligence Division of the Military Intelligence Division, headed by Major Frank Moorman; and the Code Compilation Section of the Signal Corps, headed by Howard R. Barnes, who had been commissioned a captain because of his 10 years of experience in the State Department Code Room. Both were stationed at Chaumont, 150 miles east of Paris.

Barnes managed to convince the British to reluctantly turn over a copy of their obsolete “trench code” and used it to develop The American Trench Code, of 1,600 elements, and the Front-Line Code, with 500. These two code books served as the American cryptosystems during the first crucial weeks of substantial AEF participation in the war, including in the battles of Château-Thierry and Belleau Wood (June - July 1918).[25]

As the Code Compilation Section became more sophisticated, it was able to produce more sophisticated codes, which needed to be changed regularly, and revise them in their entirety within 10 days, whereas a dumfounded British officer remarked that it would take his army at least a month to do so.[26]

Under Major Moorman, a handful of cryptanalysts initially came from enormously varied, mostly academic backgrounds (music critics, linguists and an archeologist) to support the AEF both at Pershing’s General Headquarters (G.H.Q.) and with the separate army headquarters deployed throughout the Western Front. Among the first to arrive was newly commissioned Lieutenant William F. Friedman, one of only two who had any experience at all with codes and ciphers. The G.2 A.6 unit grew to a total of 72 at its height, divided into five sections: cryptanalysis, interception of enemy telephone conversations, following enemy air artillery spotters, and checking monitored American communications for security breaches.[27]

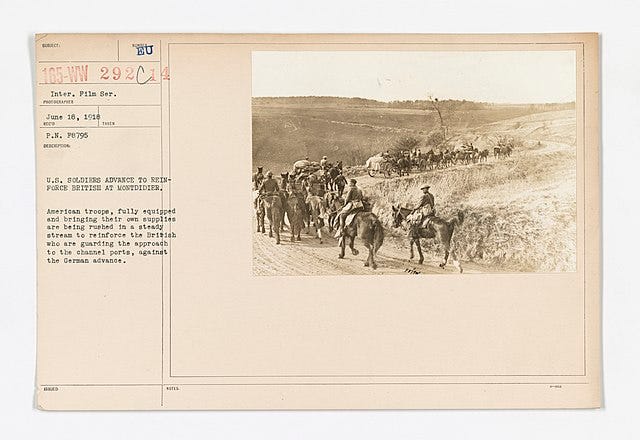

Despite G.2 A.6’s impressive advances, it was the French cryptanalyst, Painvin, who ultimately saved the day during the major German offensive that attempted to break through Allied lines on the Western Front in the spring of 1918—the offensive that necessitated the heroic actions of the U.S. Marine Corps at the Battle of Belleau Wood. The Allies knew that Germany planned to launch a climactic assault on their lines, but without knowing at least a few of the precise locations, they did not know where best to place their limited reserve troops. Painvin, by decrypting a key communication from the German High Command ordering the rapid transfer of munitions, revealed that the assault would arrive on June 7 between the towns of Montdidier and Compiègne. When the Germans arrived, the French were ready and held the line until the Allies, bolstered by the arrival of the Americans, could launch a counteroffensive in August.[28]

As early as the fall of 1918, the German government was approaching President Wilson expressing interest in an armistice.

Herbert Yardley, who ultimately was more of a self-promoter than a cryptanalyst (something most likely manifestly evident to his contemporaries), sailed for Europe in August 1918 to try to learn as much as he could from his British and French counterparts. He studied briefly with the British M.I.(b) and met Painvin, but he never gained access either to the French Foreign Ministry cryptanalytic bureau or to Room 40, the latter of which were probably were still enjoying liberal access to encrypted U.S. diplomatic communications. Yardley remained in Paris after the Armistice to head the cryptologic bureau of the American delegation to the Versailles Peace Conference.[29] By then, the size of the U.S. Signal Corps had risen to 2,712 officers and 53,277 enlistees divided between the A.E.F. and forces in the United States. [30]

In April 1919, Yardley had to return to the United States for the scaling down of Military Intelligence for peacetime conditions.[31] But this was far from the end of the story, for Yardley, W.F. Friedman, or American cryptology. Yardley and his team of civilian cryptanalysts continued to provide support to the State Department decrypting diplomatic communications during the Disarmament Conference of 1921 and throughout the 1920s, until President Herbert Hoover’s Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson, upon learning of the arrangement in 1929, summarily withdrew all State Department funds from the effort, declaring “Gentlemen do not read each other’s mail.” At that point, unemployed at the outbreak of the Great Depression, Yardley decided to write tell-all book about his experiences called The American Black Chamber, which became an instant best-seller in several countries, despite its many self-aggrandizing inaccuracies.[32]

The Friedmans, who were appalled by Yardley’s book, quit Riverbank at the end of 1920, Mr. Friedman continuing in a civilian capacity as an instructor for the War Department’s Signal Corps. He also patented two encipherment devices that served as the precursor for the World War II-era rotary-modeled devices. In 1928 he served as the secretary and technical advisor to the American delegation to the International Telegraph Conference of Brussels. By 1929 he was known as one of the world’s leading cryptologists.[33] Parker Hitt found employment with International Telephone and Telegraph, where he invented a teletypewriter cipher machine to sell to the State Department; unfortunately for Hitt, Friedman’s team tested it and were able to break its cipher in a few hours.

Thus, despite the interwar drawdown of military forces, the thread of SIGINT capacity within the U.S. Government built up during World War I was never broken. Military officers continued to receive training from the Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) that Friedman helped establish, under the watchful eye of Joseph O. Mauborgne, who by 1938 was a two-star general and the Army’s Chief Signal Officer.[34]

The serialized publications developed by W.F. Friedman to train AEF officers at Riverbank in 1917 are today extremely rare. Several of them, however, are on display at the National Cryptologic Museum, adjacent to NSA Headquarters at Fort George G. Meade, Maryland.[35]

[1] David Kahn, The Code Breakers (The MacMillan Company, 1972), at xiii-xv.

[2] Kahn at 348.

[3] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 297.

[4] Atherton’s 1916 book about her experiences, Life in the War Zone, is available through Project Gutenberg at https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/48160/pg48160-images.html (last viewed December 3, 2024).

[5] Dr. Harold C. Relyea, Congressional Research Service, “The Evolution and Organization of the Federal Intelligence Function: A Brief Overview (1776-1975), contained in Book VI of the Final Report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities,” United States Senate (U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, 1976), at 77-78.

[6] McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, at 297-98.

[7] Relyea at 89.

[8] Herbert O. Yardley, The American Black Chamber (The Bobbs-Merrill Company: Indianapolis, 1931), at 32-36.

[9] Yardley at 40.

[10] Yardley at 37.

[11] Yardley at 39.

[12] Kahn at 266.

[13] Kahn at 309-10.

[14] Kahn at 262-3, 299-300.

[15] Kahn at 317-18. Italy had entered the war in phases, starting in April 1915, when the Entente recognized its claims to the South Tyrol in Austria, Libya and western Turkey, after which Italy declared war on the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires. It then declared war on German on August 28, 1916. In March 1916, the French, British and Italians began to explore intelligence cooperation with regard to their Mediterranean interests at a conference in Malta at which MI-6 chief Captain Mansfield Smith Cumming was in attendance. In July 1917, Cumming appointed Sir Samuel Hoare to head a Special Intelligence Mission of the British Mission with the Italian General Staff, representing both MIi(c) and MI5, establishing offices in Rome, Milan and Genoa. In general the British found that rivalries between the different Italian agencies were a hindrance to effective security and counter-espionage. Keith Jeffery, MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909-1949 (Bloomsbury Publishing: London, 2010), at 123-24.

[16] Kahn at 370-74.

[17] Seema Sohi, Echoes of Mutiny: Race, Surveillance & Indian Anticolonialism in North America (Oxford University Press: New York, NY, 2014), at 165-66.

[18] Sohi at 177.

[19] Sohi at 185.

[20] Kahn at 372.

[21] Sohi at 186.

[22] Kahn at 373-74.

[23] David Kahn, The Code Breakers (The MacMillan Company, 1972), at 325.

[24] James G. Harbord, The American Army in France 1917-1919 (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1936), pp. 94-95, quoted in Relyea at 86.

[25] Kahn at 326-27.

[26] Kahn at 329.

[27] Kahn at 333.

[28] Kahn at 340-47.

[29] Kahn at 354-55.

[30] Relyea at 89.

[31] Relyea at 116.

[32] Kahn at 355-61.

[33] Kahn at 384-85.

[34] Kahn at 388-89.

[35] See https://www.nsa.gov/History/National-Cryptologic-Museum/Contact-Us/ (viewed January 9, 2025).