That time white women used Puerto Ricans as guinea pigs for birth control pills

An anecdote from Daniel Immerwahr's How to Hide an Empire that tracks with the recent Internet meme "White women are the men of women."

Of my two Christmas gifts, I’ve finished the Immerwahr book, How to Hide an Empire and am now a little more than halfway through G-Man.

Both fantastic books, but two completely different types of history books. Reading How to Hide an Empire is a bit like grocery shopping at Trader Joe’s: You can’t go in there seeking any particular staple, but chances are you’re going to find something you didn’t know you needed until you see it. G-Man, by contrast, is sort of a Buc-ee’s: If you need anything at all on J. Edgar Hoover, chances are it’s there.

Anyway, the historical anecdote I didn’t know I needed until I read it in How to Hide an Empire is the story of the birth control pill.

If you recall, at the time the United States invaded Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American War, the Puerto Ricans welcomed the U.S. invaders with open arms. Shortly after U.S. forces invaded the city of Ponce, “[f]ive companies of the municipal fire brigade paraded before them in their honor,” signs reading “English Spoken Here” began appearing outside local shops, and the wealthier local citizens even opened a Red Cross hospital for the U.S. Army at their own expense. (Ivan Musicant, Empire by Default, 532-33). This is at footnote 61 of my previous post:

I’m not entirely sure how the image of Puerto Rico on the U.S. mainland devolved from this auspicious beginning to “Puerto Ricans are dirt poor and they’re making too many babies”; I’m going to guess it has something to do with Puerto Rico not having a vote in Congress that could direct spending into your district. But by the 1920s even Luis Muñoz Marín, who in 1948 became the first democratically elected governor of Puerto Rico, believed the problem in Puerto Rico stemmed not from lack of considered economic development but from overpopulation. He said the problem of hunger could only be solved in one of two ways: more food or fewer mouths.

One solution was to facilitate large-scale emigration of Puerto Ricans to the mainland, particularly New York City (Muñoz Marín had lived in Greenwich Village in the 1920s). This started in earnest in the late 1940s, and it resulted in such a profound demographic shift that they made a musical about it:

But senior U.S. officials, including Presidents Herbert Hoover and Franklin Delano Roosevelt, agreed with Muñoz Marín that birth control was additionally a necessity; as one official put it, the problem was that the island’s women “kept shooting children like cannon balls at the rigid walls of their economy.” It was easy enough to introduce the concept of birth control; without the self-governance to which U.S. states were entitled, there were no state or local laws in Puerto Rico against it of the type that the U.S. Supreme Court eventually struck down in Griswold v. Connecticut (1962) as inconsistent with the U.S. Constitutional right to privacy.

More importantly, there was nothing stopping the U.S. medical establishment from using disenfranchised Puerto Ricans as human subjects in medical experiments (so much for privacy, bodily autonomy, etc.). Indeed, this precedent had already been set by Dr. Cornelius Packard “Dusty” Rhoads, who had pioneered remedies for anemia in the 1930s for the Rockefeller Foundation’s International Health Division by experimenting on the many patients he treated in San Juan. In a letter to a colleague, he described Puerto Ricans as

“beyond doubt the dirtiest, laziest, most degenerate and thievish race of men ever inhabiting this sphere. It makes you sick to inhabit the same island with them. They are even lower than Italians. What the island needs is not public health work, but a tidal wave or something to totally exterminate the population…I have done my best to further the process of extermination by killing off 8 and transplanting cancer into several more.”

(This is in How to Hide an Empire at p. 144, but you can also read the letter in its entirety on Rhoads’ Wikipedia page).

One might well imagine the level of regard such a medical establishment would have for the Puerto Rican women who were purportedly “shooting out children like cannon balls.” According to Immerwahr, at least one hospital refused to admit women for their fourth delivery unless they agreed to be sterilized afterwards. By 1965, more than a third of Puerto Rican mothers between the ages of 20 and 49 had been sterilized.

It was around this time that a biologist and researcher in Massachusetts named Gregory Pincus began to wonder whether the global “population explosion” could be contained via some sort of contraceptive pill or shot. Unfortunately, being Jewish, he didn’t have some of Rhoads’ connections and couldn’t obtain the funding to answer this question.

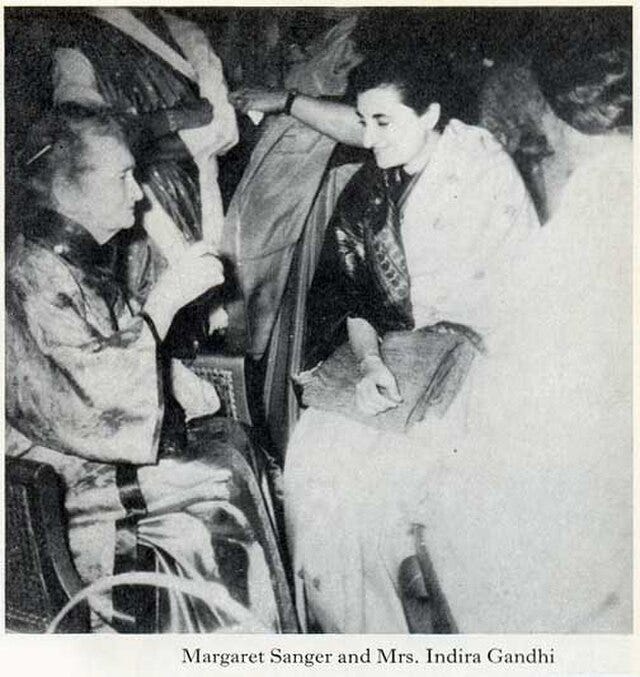

Here’s where the white women came into the picture: Pincus took his idea to Margaret Sanger, the founder of Planned Parenthood, and the heiress Katharine Dexter McCormick.

For the rest of this story I’ll quote Immerwahr at pp. 248-49:

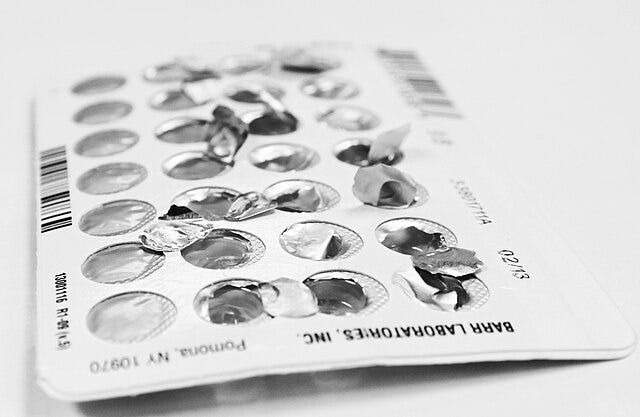

“McCormick was impatient for large-scale field trials. ‘How can we get a “cage” of ovulating women to experiment with?” she asked Sanger.

“The team considered tests in Jamaica, Japan, India, Mexico, and Hawai’i. In 1954 Pincus visited Puerto Rico and was suitably impressed. Here was a place where they could undertake, as Pincus expressed it to McCormick, ‘certain experiments which would be very difficult in this country.’

“The first experiment used medical students at the University of Puerto Rico. Despite having their grades held hostage to their participation in the study, nearly half dropped out—they left the university, were wary of the experiment, or found it too onerous. The researchers then tried female prisoners, but that plan fizzled too. In 1956 they began a large-scale clinical trial in a public housing project in Rio Piedras.

“The pill that Pincus’s team administered had a far higher dosage than the pill does today. Many women complained of dizziness, nausea, headaches, and stomach pains. The lead local researcher concluded that the pill caused ‘too many side reactions to be acceptable generally.’ Pincus, however, was undaunted. He blamed the complaints on the ‘emotional super-activity of Puerto Rican women’ and tried giving some the pill without warning them of its side effects…

[The experiments continued the following year.] “One researcher noted that the women appeared to be suffering from cervical erosion (‘whatever you call it, the cervix looks “angry”’), but the tests continued. Stopping them would mean delaying approval from the Food and Drug Administration, which the researchers were eager to get.

“They got it. in 1960, basing its decision largely on the Puerto Rican trials, the FDA approved the birth control pill for commercial sale.”

So there you have it, white women: this is how we developed the pill, all under the approving gaze of McCormick and Sanger. Why did we have a “cage” of ovulating, voiceless women to experiment on in Puerto Rico? Because of the Spanish-American War of 1898 (stay tuned for my forthcoming podcast, “Nobody Gives a Shit About the Spanish-American War”).

I’m not sure whether or how this story might eventually be included or referenced in my book. I have a long ways to go before I’m into the 1950s. Also, I haven’t yet figured out what to do with public health and its implications for mass surveillance; I don’t want to get all weird and RFK Jr. about it. But I’ve been covering a lot of manly-man history thus far, and occasionally in my research I do wonder “and what were the women doing while all this was going on?” When I have a good answer, I include it.

So again, kudos to Daniel Immerwahr for including a story that I didn’t know I needed to read until I’d read it. As for the meme “white women are the men of women,” I frankly was already getting a kick out of it, but this story takes its meaning to a whole new level.