Yale and the Chinese Abolitionists

My latest rabbit hole; this time it's President Grant's fault.

Before I get on with The Great Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 Part 2 (a continuation of this post):

I have to tell you this story I just ran across. It’s not wholly unrelated, as it also concerns Chinese coolie labor on sugar plantations, but it takes us back in time a few decades and to a different part of the world. Here’s what sent me down this latest rabbit hole:

On December 6, 1869, President Ulysses S. Grant asked in his opening message to Congress for “such legislation as will forever preclude the enslavement of the Chinese upon our soil under the name of coolies, and also prevent American vessels from engaging in the transportation of coolies.” At the time, there was quite a bit of xenophobic chatter out of California regarding the massive influx of Chinese immigrants. However, with minor exceptions, these immigrants were not coming to California under coolie labor contracts or working under slave-like conditions; in fact, they were becoming so successful as merchants, restauranteurs and laundry operators that the objections to them were coming from their white business competitors. So, where did Grant get this idea that the Chinese coolie labor trade was tantamount to slavery and that the United States had a moral imperative to do something about it?

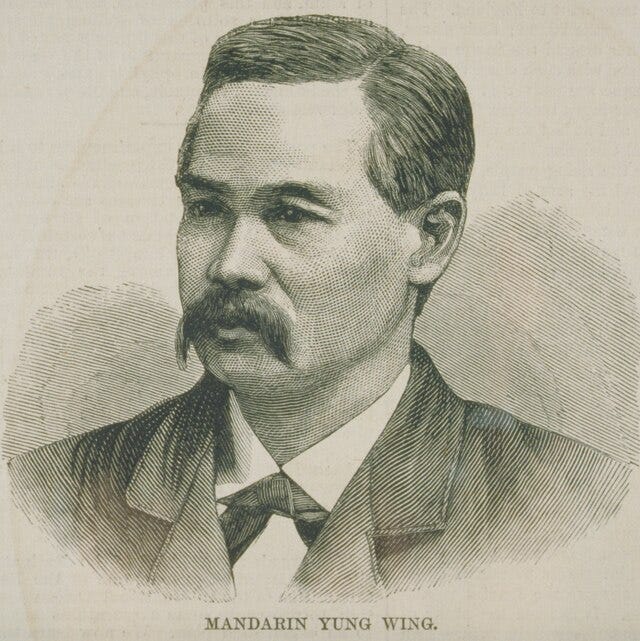

While I can’t prove it unless I’m willing to spend a few weeks poring over original source material at the College Park National Archives, I think he might have gotten it either from a Chinese Yale graduate named Yung Wing; Chen Lanbin, the first Chinese ambassador to the United States; or one of their close associates. And this is where this story gets interesting.

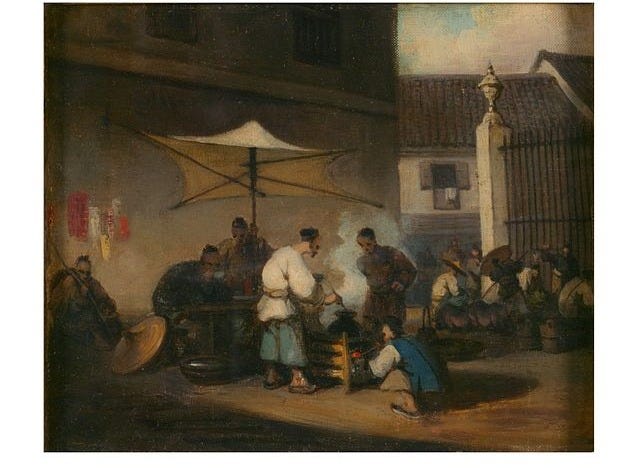

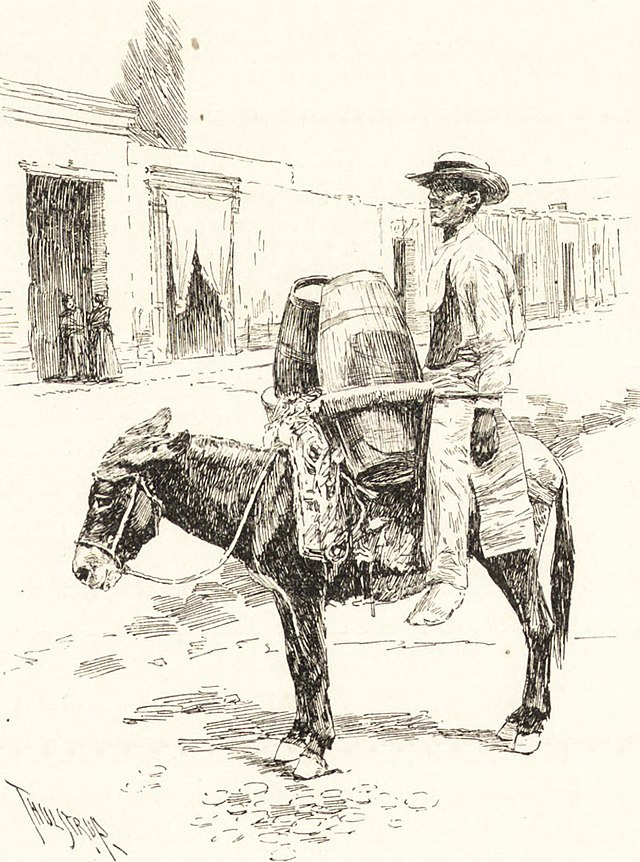

Roll the clock back even further. In 1834, the British formally outlawed the trans-Atlantic African slave trade. But this did nothing to address the continuing perceived need for massive numbers of unskilled field laborers in European colonies like Cuba, where the Spanish were trying to make a mint off the sugar plantations—in competition with the sugar plantations in Hawai’i (See? It all leads back to the Oahu sugar strike). What did they do? Without skipping a beat, they, along with British and Portuguese shippers in Hong Kong and Macao, set up a new trans-Pacific pipeline of Chinese coolie laborers into the Americas: 18,000 to the British Caribbean, 95,000 into the silver mines and guano fields of Peru, and 125,000 into Cuba, where they labored alongside slaves. Moreover, many of the laborers were either defrauded or essentially forced into indentured servitude by their clan debtors in China. Two Spanish cousins, Pedro and Julián Zuleta, managed the Pacific coolie trade out of London through a large merchant house.

As early as 1847 the shipment of Chinese coolie laborers to Havana had already become, in the words of the English consul in Amoy (Xiamen), a “hateful topic” among the Chinese, who referred to it as “selling piglets” (mai zhu zai or 卖猪仔). The Spanish referred to it as la trata amarilla, or “the yellow trade,” which is helpful to know in case you were wondering whether some sort of racial bias was at play here.

By 1866, U.S. diplomats in China under the administration of President Andrew Johnson were well aware of the controversy, assuring one another in correspondence with the State Department in Washington that "[t]he regulations prescribed by the Chinese, French, and English governments are well calculated to test the fact that such emigration is free and voluntary" (they were not). In 1868, the U.S. Legation to the Hawai’ian Kingdom reported with concern that “a cargo of Japanese coolies” had recently arrived in Honolulu on the British ship Scioto, and that U.S. intervention might be necessary "to prevent the inauguration of a traffic more odious than the coolie trade of China."

Thus, Grant, who took office on March 4, 1869, could in theory have relied solely on the reports of his own diplomats to come to the conclusion that the Chinese coolie trade was a new form of enslavement. He would more likely have seen this as a genuine human rights problem than Andrew Johnson, who, let’s face it, was kind of a douche. But in 1872, the story gets even more interesting.

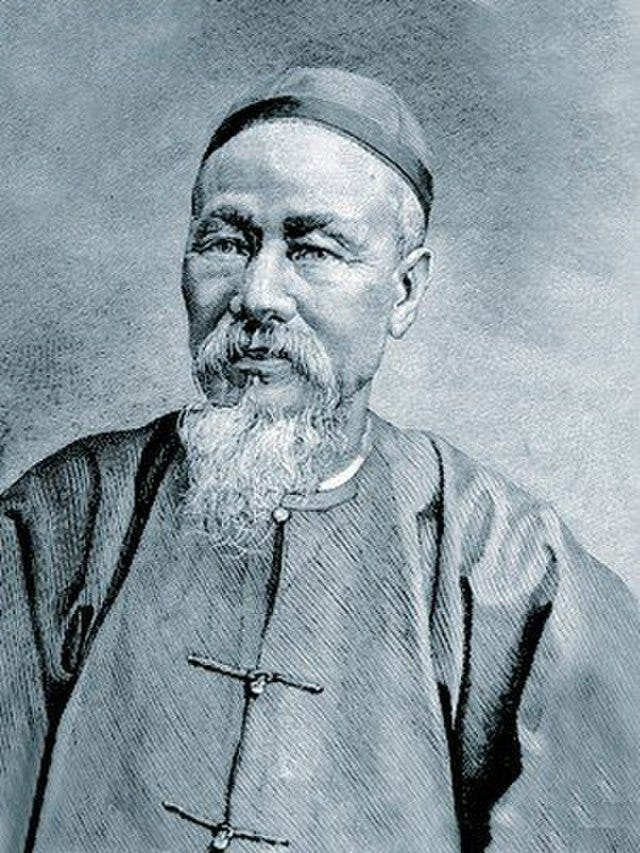

In 1872, the Qing Dynasty, at that time effectively ruled by the Empress Dowager Cixi, established a Chinese Educational Mission (CEM) in Hartford, Connecticut, headed by a distinguished civil servant and graduate of the prestigious Hanlin Academy, 56-year-old Chen Lanbin (陳蘭彬). While Chen Lanbin’s English proficiency was quite limited, the actual mastermind behind CEM was Yung Wing, a proud Yale graduate—the first Chinese graduate of any American university, as a matter of fact—who had also become a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1852.

Yung “electrified the American cultural imagination,” converting to Christianity—always a crowd-pleasing move among white Americans, helping the heathens find Jesus—and would go on to marry an American woman named Mary Kellogg, to the delight of his friend and pastor Joseph Twitchell, who was in turn a close friend of Mark Twain.

CEM brought a total of 120 Chinese students to live with American host families, and through Yung and his Boola Boola buddies, they became quite the local sensation. Seriously—this is the type of crowd they were hanging with:

Connecticut Senator Joseph A. Hawley was just one of many of Yung’s close confidants. While California wallowed in its xenophobia towards its Chinese coolie laborers, the East Coast elites were blossoming into outright Sinophilia. It surely didn’t hurt matters that many of the strapping young Chinese men of the CEM were leaning in—cutting off their pigtails, mastering Western table manners, rowing on crew teams, and even making their way with the local ladies while learning to sing ridiculous Yale fight songs.

But yes, about those coolie laborers. In 1874, the Qing Foreign Ministry directed Chen Lanbin to head an investigative mission to Cuba to examine the working conditions on the Cuban sugar plantations. Chen recruited H. L. Northrop, an American from Connecticut, as his Spanish interpreter; Northrop promptly branded Chen with the title presidente de la comisión china (president of the Chinese commission), in an effort to earn him respect with Cuban politicians and planters. Other members of Chen’s team included Ye Shudong, a language teacher later to be recommended as Chinese envoy to the United States, Spain, and Peru; Chan Lun, a Hartford student; H.T. Terry, a Hartford citizen; and Zeng Laishun, who would go on to work as the official interpreter for the U.S. Consulate in Zhenjiang.

Upon arrival in Cuba, the group received a glowing reception from the Havana press, and quite the opposite from both the Cuban government and the sugar plantation owners. About 50,000 coolies were working on Cuban sugar plantations in 1874, and the Chinese commission eventually interviewed a total of 2,841. The privileged young Chinese men who had been enjoying their time at Yale and who accompanied Chen on the mission now “confronted Chinese boys in their early teens and barely older than their Connecticut peers, lured into promises of higher pay and a better life in the Caribbean, only to be forcibly deprived of their contract papers.” On one occasion, a plantation “administrator”

interrupted the investigative session after only one-third of the interviewees had reported their experiences, dispersing the remaining two-thirds ‘with blows and kicks’. Coercion and intimidation were on open display. “Ordinarily, too, the administrators and overseers stood by whip in hand’, the Commissioners reported. Punishment of coolies was frequently reserved for the aftermath of the interview sessions.

When the group returned to Connecticut and shared their findings with Yung Wing, Yung and his friend Twitchell teamed up with Dr. Wilberforce Kellogg, a physican and Yung’s future brother-in-law, and another small coiterie of Chinese interpreters to undertake a similar mission to Peru. They made similar findings. According to Twitchell’s diary of the trip, Yung, upon his first interview session with local coolies, said “he had cried for the miseries of his people. The more he hears the deeper he feels and the louder he hears his call to act.”

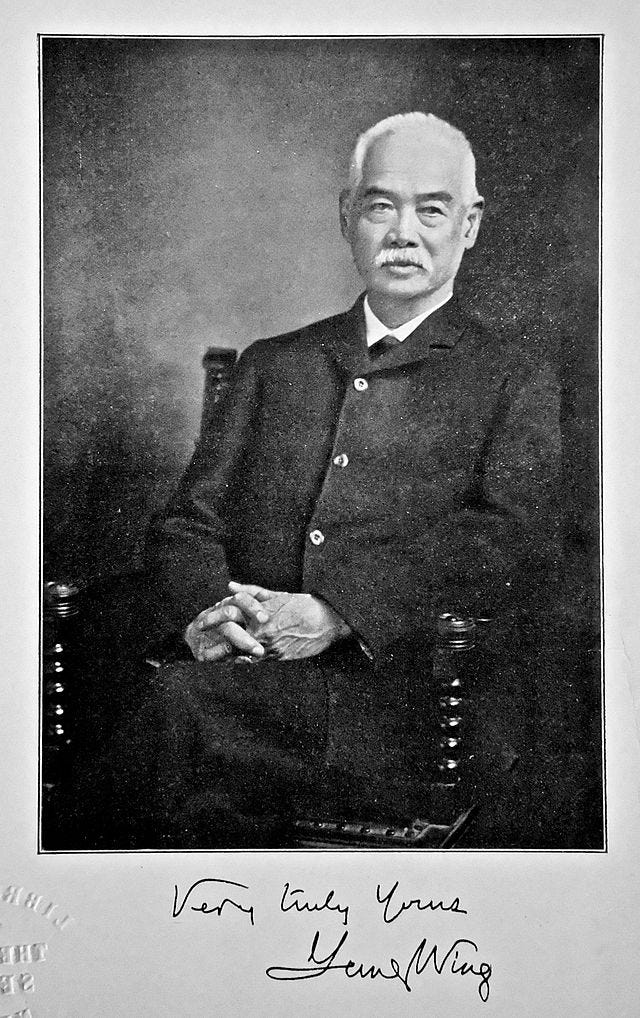

The outcome of these two missions, one of the earliest known international human rights investigations and one led by Chinese officials with white Americans in a supporting role, was profound. The Portuguese coolie trade out of Macao was terminated almost immediately, as opposed to continuing to fool around with “regulations.” The Empress Dowager was generally a moderate who sometimes resisted change. On August 10, 1875, however, the Qing throne was finally convinced that, given the “oppression and unspeakable suffering of Peru’s ‘more than a hundred thousand Chinese labourers,’” formal Chinese diplomatic representation had become a necessity. Chen and Yung were promptly appointed as China’s first diplomats in the United States, Spain, and Peru. This was followed in 1877 by a treaty between Spain and China and the termination of all coolie contracts in Cuba.

Within the United States, the reports were not nearly as impactful. Chen served in the United States until December 1881 at the Chinese consulate in Washington, followed by San Francisco. One of his students, Cai Xiyong, returned to China that same year with the first-ever Chinese translation of the U.S. Constitution. By that time, however, the initial Sinophilia on the East Coast among Yung’s fellow Yalies had been long since overcome by the Sinophobia of California, culminating in the notorious Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

Yung Wing and his wife Mary had two sons, Morrison and Bartlett (the first named after Robert Morrison, a Scottish Protestant missionary to Macao). Yung was also recalled to China in 1881, but he returned to the United States in 1883 due to Mary’s dire health condition; she died in 1886. While working in China again for the government during the Hundred Days' Reform, he suddenly found himself on the wrong side of the Empress Dowager following the 1898 coup in which she engineered the overthrow of Emperor Guangxu. With a $70,000 price on his head, Yung fled for Hong Kong. Then, despite the U.S. State Department’s long-standing reputation for being "pale, male and Yale," he learned that his Yale connections could only take him but so far. In 1902 he made contact with the U.S. Consul there in preparation for his return to the United States, only to be told that his U.S. citizenship had been revoked pursuant to the Nationality Act of 1870. He still had some friends who were able to arrange for his surreptitious entry in order to see his son Bartlett graduate from, of course, Yale. He eventually died in Hartford in 1912.

As for Cuba and the United States, the exploitation of slave and coolie labor on the sugar plantations did not end with the treaty between Cuba and Spain.

Slave labor was employed by both sides in the first Cuban War for Independence (1868-78), and conditions in Cuba under Spanish rule remained so horrific that they became one of the primary drivers of the Spanish-American War of 1898.

This led to the U.S. acquisition of the Philippines, which in turn provided a fresh source of coolie labor for the sugar plantations of Oahu following a major Japanese-led labor strike there in 1909.

And here we are, right back at the Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920.

The primary source for this post is Steffan Rimner, “Chinese abolitionism: the Chinese Educational Mission in Connecticut, Cuba, and Peru,” 11 Journal of Global History, Cambridge University Press (2016), 344-364.

Yung Wing published an autobiography in 1909 entitled My Life in China and America, which anyone can access on the Internet Archive.

More details about Chen Lanbin’s life are harder to come by in English language sources, except for the intriguing piece by Rongliang Niu, “A study of Chen Lanbin’s Translation Patronage Behavior on the Chinese Translation of the US Federal Constitution,” available here.