The Great Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 Part 1

How an event you've most likely never heard of connects to absolutely everything else

Students of immigration and labor relations in the United States can usually rattle off a few major events from the early 1920s that shaped both fields into their modern form: the wartime suppression of the IWW or the “Wobblies,” the rise of the American Federation of Labor, the widespread strikes of 1919, the Red Scare, the Palmer raids (precipitated by a bomb that blew off the front of Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer’s house, which I discussed here (towards the end):

the Sacco and Vanzetti case, and general fear of and animosity towards Southern and Eastern European immigrants leading up to the Immigration Act of 1924. As I have been exploring in some of my most recent posts,

developments in immigrant regulation have also been enormously important to the establishment of what we would today call the modern “surveillance state” through identity intelligence: fingerprinting, passport photos, large-scale medical screening, and general enforcement capacity.

But the overall purpose of my project (see:

is to examine whether and to what extent the fateful decision by the United States in 1898 to acquire a European-style colonial island empire is at the root of intractable modern debates over warrantless Internet surveillance by the NSA. That is what brings us today to the Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920.

As this story unfolds, keep this thought in the back of your mind: What is the single most important historical event that finally prompted the United States to create a permanent, peacetime intelligence-gathering capacity? The answer, for most people, is the December 7, 1941 Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor (the definitive work on this topic is still Roberta Wohlstetter's1962 Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision if you want to skip ahead). If my scholarship is hard to navigate sometimes, you can often orient yourself through references to geographical places rather than people—in keeping with Jared Diamond’s general thesis that geographical advantages have largely shaped the course of human history. The Philippines is one of those places that I return to repeatedly (that’s why it’s in the working book title), and so, it turns out, is Pearl Harbor.

The Birth of the Hawai’ian Sugar Industry

For most of Hawai’ian history starting around 600 A.D., sugarcane harvesting has been essentially this:

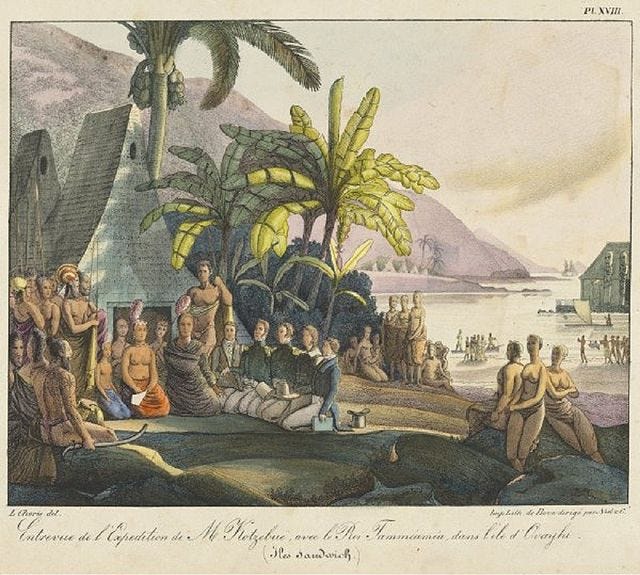

Sugar cane was brought to the Hawai’ian islands by early Polynesian explorers; it was being cultivated for home use and on small plantations (though not as refined sugar) when Captain James Cook first landed on the islands in 1778. In 1835, only one year after Britain abolished slavery in all of its colonies, William Hooper of Ladd & Co. started the first sugar plantation operated by foreigners in Kōloa, Kauaʻi.[1]

While Hawai’i was not a British colony but a nominally independent kingdom until 1898, the British abolition of slavery, as “perhaps the most significant legal transformation of labor relations, and hence the terms of contract, in the nineteenth century,” affected it deeply.[2] It meant that, if a sugar industry were to be established on Hawai’ian soil, there would need to be a reliable source of unskilled or “coolie” labor to harvest and process the crop that would almost certainly have to be provided by foreign migrants. The overwhelming majority of the Hawai’ian native population died off almost immediately from exposure to Western disease, for all the reasons discussed in Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel. From an estimated 300,000-600,000 Hawai’ians who inhabited the islands at the time of Cook’s arrival, by 1800 the population had already declined 48% (by the 1920 census, the native Hawai’ian population was under 24,000).[3]

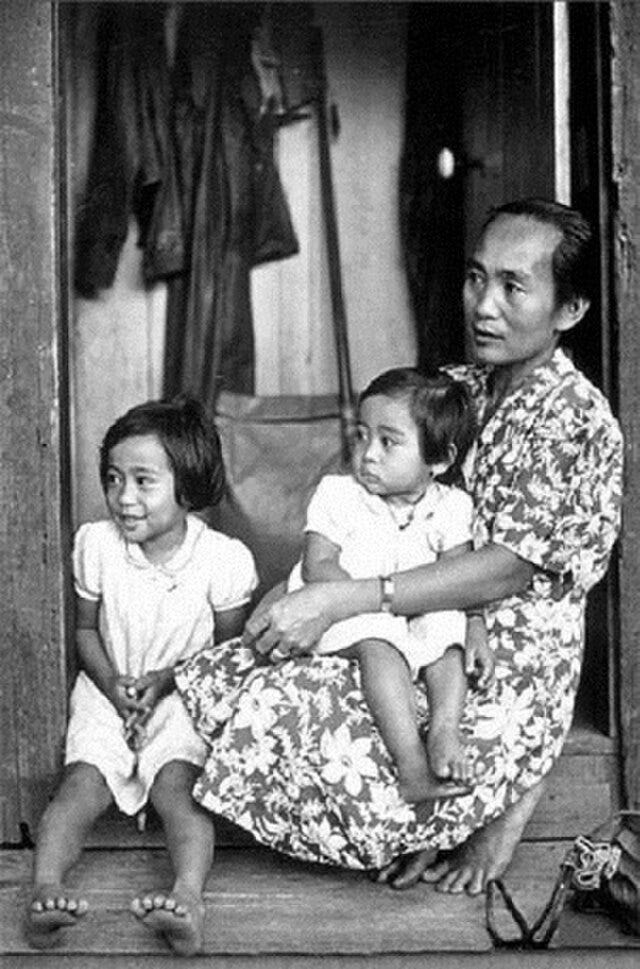

Those few who remained maintained their traditional cultural attitude towards work called kanaka—working more or less when the mood strikes you—and were disinclined to engage in sugar cane harvesting all day long under the hot equatorial sun under the threat of bullwhips from horse-mounted overseers, a process that now more closely resembled this:

The Kingdom of Hawai’i opened up land ownership to foreigners in 1848, which enabled mostly American investors to acquire the large amounts of land required for the mass cultivation of sugarcane. These white plantation owners, along with a slew of white Christian missionaries, had at this point already become more or less the dominant haole class in Hawai’ian society and had positioned themselves as ministers, court advisors and sometimes spouses to the increasingly beleaguered and isolated native Hawai’ian ruling monarchs (the descendants of these “great” families are portrayed in the 2011 George Clooney film and 2007 novel The Descendants).[4] But the sugar plantation owners, in order to stay competitive with Cuba, would need to maintain expensive irrigation systems, as Hawai’i tends not to receive the same amount of rainfall as Cuba. Thus, they needed an especially cheap source of foreign labor—the more docile and obedient, the better. In 1850 Hawai’i enacted the Masters and Servants Act, legalizing contract labor.[5] The same year, the plantation owners created the Royal Hawaiian Agricultural Society to solicit foreign laborers. In subsequent years, they would also create the Planters’ Society and the Planters’ Labor and Supply Company, which in 1895 renamed itself the Hawaiian Sugar Planters’ Association or HSPA; the HSPA would become a key player in the 1920 Oahu sugar strike.[6]

The sugar industry first imported Portuguese and Chinese coolies. The Portuguese did not come from the European continent, but from the Azores, Madeira, and Cape Verde Islands off the coast of Africa; in fact, many of them were so dark skinned that for a number of years they were thought of by the haole ruling elite as more or less black,[7] or else a slightly inferior Southern European stock of mixed Moorish descent, and thus part of the laboring class. That said, they were considered superior to Asians and often placed in the in-between roles of foreman/overseer or luna.[8]

Chinese laborers were available in abundance due to the disruptions presented by the Taiping Rebellion, and approximately 50,000 Chinese came to Hawai’i between 1852 and 1887. Most of these laborers, however, apparently also did not enjoy working 10-hour days harvesting sugar cane with Portuguese lunas on horseback whipping them.[9] Chinese laborers would save their money, and when their 3- or 5-year contracts were up, they would leave the sugar cane fields and either open local businesses or leave for California. By 1882 only a quarter of the Chinese brought in to harvest sugar cane were still on the plantations.[10] Another source of cheap foreign labor would be needed, the more docile and compliant, the better.

Hawai’i comes to Japan, Japan comes to Hawai’i

As early as 1868, an American merchant an named Eugene M. Van Reed, who served as the Hawai’ian consul in Kanagawa, Japan, had boasted to Hawai’ian Foreign Minister Charles de Varigny that “[n]o better class of people for Laborers could be found than the Japanese race, so accustomed to raising Sugar, Rice and Cotton, nor one so easily governed, they being peaceable, quiet, and of a pleasant disposition.”[11] Until May 1866 the Tokugawa Shogunate had not allowed Japanese people to emigrate at all; however, the Meiji government by the 1880s had different priorities. As I discussed in this post:

Japan, along with China and the Ottoman Empire, was desperate to “modernize” along Western lines in order to avoid Western domination and assert itself militarily. Its new industrialization and fiscal policies, however, had a severe impact on the nation’s farmers, particularly in southwestern Japan, with many of them losing their land due to inability to pay the new land taxes. In 1885, two-thirds of a village of 80 households in Fukuoka had sold all their belongings by public auction and were reportedly “waiting for death.”[12]

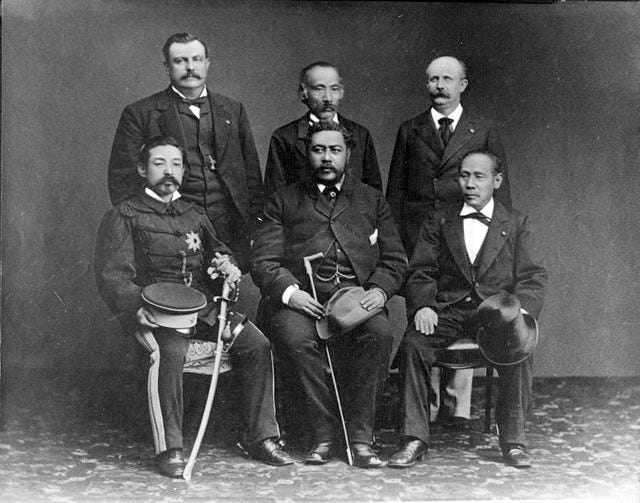

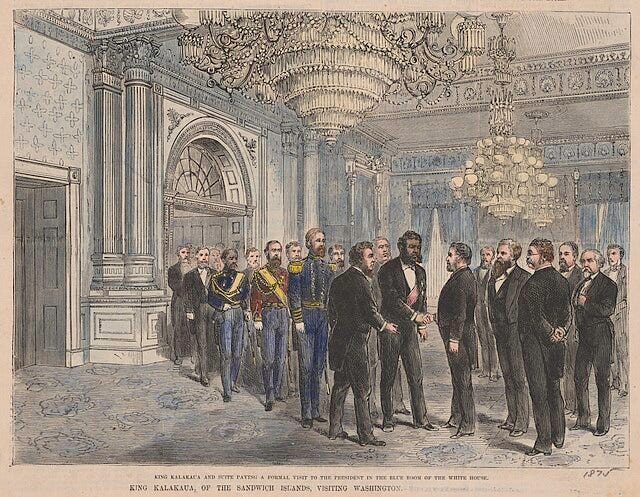

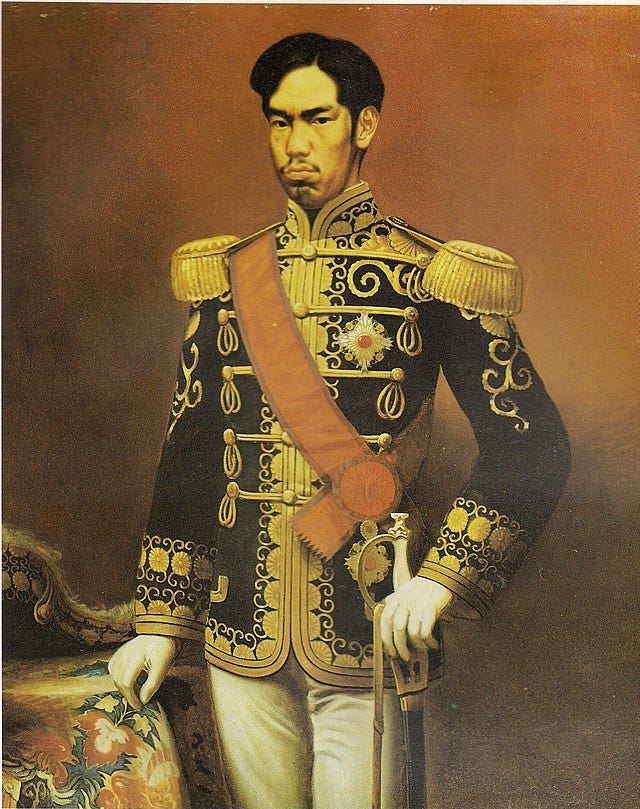

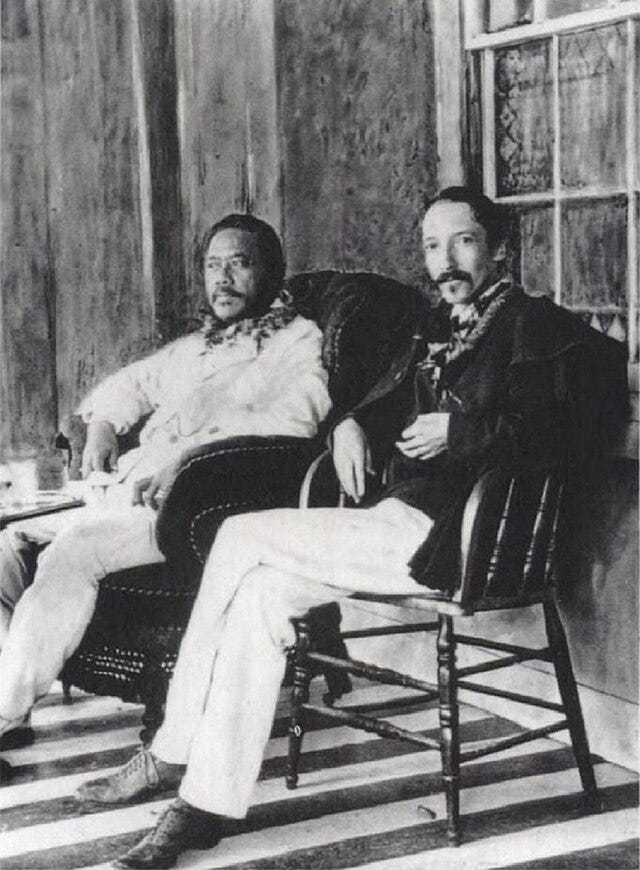

It was within this context that Hawai’i and Japan entered into a Treaty of Amity and Commerce in 1871. King Kalakaua made an official visit to Japan in 1881 and met with Emperor Mutsuhito. In an apparent Hail Mary pass at saving his country from permanent white haole domination, Kalakaua proposed a marriage between Mutsuhito’s son Prince Sadamaro, then a cadet at the new Japanese Naval Academy, and Kalakaua’s then-six-year-old daughter Princess Kauilani. The marriage presumably would have united the Empire and the Kingdom. The Japanese Foreign Minister politely declined the proposal the following year;[13] in the meantime, the haole plantation owners were already putting pressure on the Japanese government to start shipping Japanese laborers to the sugar and pineapple plantations.

The haole had another reason to shift from Chinese to Japanese labor, which was the passage of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 in the United States. Already positioning Hawai’i for eventual U.S. annexation, the haoles knew they would have to show U.S. policymakers that they were as committed to excluding Chinese immigrants and maintaining white supremacy as the U.S. mainland. In fact, by 1898, when Hawai’ian President Sanford Ballard Dole (yes, if you’re thinking “Dole pineapple?” that is the correct association) was lobbying the U.S. Senate for annexation, they had decided to count the Portuguese as “white” and most of the rest of the minority population as Polynesian, maybe brown, but definitely not Black.[14]

It took Japan and Hawai’i until 1886 to sign a labor treaty facilitating the large-scale emigration of Japanese laborers to work on the sugar plantation. The Japanese government wanted to supervise the program directly for several reasons. First, the remunerations that the workers would be sending home, amounting to 2 million yen annually, was not insignificant, especially given the debts that Japan was incurring as a result of its militarization.[15] Large-scale emigration and the creation of Japanese expatriate communities overseas also created a market for Japanese exports.[16] Second, it regarded emigration as an international relations issue, not simply a domestic or labor issue, which is why it sought a government-to-government treaty. A 1901 best-selling book by Sen Katayama called Tobei Annai (Guide to Going to America) cast emigration in particularly patriotic terms:

For our country Japan to build up a strong power in the Orient and to attempt to achieve an independent destiny, Japan must promote thriving industries…That is to say, our country Japan should not remain an isolated island in the Orient but should pursue its advantage by expanding into the rest of the world…It is my deepest belief that our fellow Japanese who depart their country and brave the vast wild ocean to enter another land, engage in business abroad, and make themselves economically viable are the most loyal to the Emperor and patriotic among our countrymen.[17]

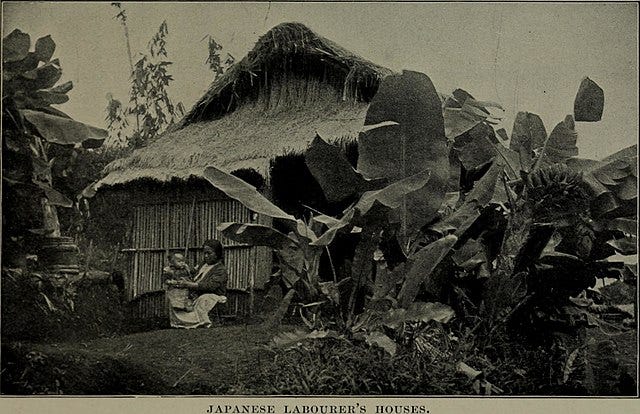

Third, it had a genuine interest in ensuring its citizens were reasonably well-treated. Any issues involving physical abuse, unsafe conditions or blatant race discrimination were to be brought to the attention of the local Japanese consulate in Honolulu,[18] which had been established there in 1885, the first Japanese Consul General having accompanied the first group of Japanese laborers to arrive in Hawai’i by ship.[19] The Japanese Consulate soon had its hands full, as it turns out that Japanese laborers also do not, for the most part, enjoy working 10-hour days harvesting sugar cane in the hot sun with overseers whipping them while earning $15 a month (although this was still more than they were earning at home). Disputes between the laborers and their immediate overseers, often involving allegations of violence or physical mistreatment, were the most common, as the plantation owners were largely removed from the situation except on basic issues such as base salaries.

Compared to coolie laborers of most other nationalities working in Hawai’i, the Japanese tended to be more literate because of the quality of children’s primary education in Japan at that time. Only 1.2 percent of Japanese laborers in Hawai’i were illiterate, while the average rate of illiteracy of all remaining groups was 28.2 percent.[20] The Japanese community imported newspapers from Japan and soon established their own local Japanese-language press as well. Despite their literacy, very few Japanese made it into the overseer or foreman class, so these literate individuals were sometimes supervised by illiterate lunas. A few Japanese were eventually employed by the planters as interpreters, and, like the Japanese consular officers, were often called upon to mediate the sometimes violent disputes between laborers and overseers. The person whose house was destroyed by dynamite during the Oahu sugar strike of 1920, Juzaburo Sakamaki, was an interpreter.

The consulate was additionally responsible for reporting back to the Japanese government general information about the size of the Japanese population in Hawai’i in relation to other nationalities and ethnic groups; crimes committed by Japanese nationals; and the organizations Japanese nationals in Hawai’i were establishing. “Government officials were interested in the movement of the immigrants after they finished their initial contracts. Would they stay and work on the plantations, or would they return to Japan?”[21] These reporting responsibilities arose during an era in which Japan, like many Western nations, was just beginning to establish an intelligence-gathering apparatus, with military and naval intelligence taking the lead but with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MOFA) also establishing a SIGINT capacity capable of intercepting Chinese diplomatic traffic.[22] In the late 19th century, MOFA funds were made available to consuls in port cities for reporting on the movement of naval vessels.[23]

Japan and the United States: Two Emerging Pacific Rivals

By the time Japan had established a consulate in Honolulu, Hawai’i had already entered into a Treaty of Reciprocity of the United States in 1876, an arrangement hugely advantageous to the planters as it allowed them to sell sugar and rice in the United States duty free. In exchange, the U.S. Navy was given exclusive access to Pearl Harbor (see, there it is) for use as a coaling station, repair base, and anchorage.[24]

The Japanese consulate may well have monitored the U.S. Navy’s activities. Certainly, it would have reported significant events in Hawai’i to MOFA, particularly the 1893 coup that deposed Queen Liliuokalani and set up a white minority provisional government that now began to actively pursue annexation by the United States.[25] In fact, in response to the coup, Japan sent the warship Naniwa to Hawai’i, ostensibly to protect the lives and property of Japanese residents, in much the same spirit as the United States had sent the U.S.S. Maine to Havana in 1898 in response to domestic unrest.[26]

The demand for Japanese laborers in Hawai’i became so great that Japan’s Emigrant Protection Ordinance, enacted in 1894, opened the door for private Japanese emigration companies to facilitate movement to the islands. Within the first four years alone, over 13,000 Japanese laborers left for Hawai’i through these private companies.[27] A large number of the founders of and investors in these companies came from the shizoku or former samurai class;[28] members of this class could be rebellious, with some of them having staged a failed counter-revolution against the Meiji government in the late 1870s, and they appear to have introduced a rougher element into Hawai’i.

Some of the Japanese agents of these companies working in Hawai’i had strong political ties to the radical, anti-government political party Jiyuto.[29] They also gained a reputation for high living and immoral behavior, frequenting geisha houses and facilitating the immigration of both prostitutes and petty gangsters. Japanese authorities eventually brought criminal charges against a number of these companies and their individual agents for fraud, extortion, falsification of emigrant registers and health examination reports, and selling ship passage tickets far above the normal cost.[30]

With the assistance of these emigration companies, the number of Japanese expatriates in Hawai’i, mostly young men, increased exponentially: 12,360 in 1890, 22,329 in 1896, and 56,230 by 1900.[31] The sheer number of laborers, alongside the obviously very keen interest in them by the Japanese government, began to raise Americans’ suspicions of the Meiji government’s motives. In fact, in 1898 the white interests running the Hawai’ian government finally achieved their goal of U.S. annexation of Hawai’i by convincing policymakers that Japan had only been exporting its laborers there as part of a covert, long-term plan to conquer the islands themselves.[32] The plantation owners, meanwhile, tried to balance out the Japanese domination of the work force by recruiting at least 10 percent white workers, which was difficult without offering Europeans much better working conditions than the Asians. “Records for 1896 show that while Japanese were given transportation costs plus wages, Germans were paid three times the wages of Japanese and given board as well. Rather than the shabby row houses allotted to Japanese, single-family houses were the norm for whites.”[33]

To Japan, the United States’ annexation of not only Hawai’i but also the Philippines that same year marked U.S. entry onto the world stage as a rival Pacific naval power, with plans to build a major U.S. naval base in the Philippines at Subic Bay. While the two powers initially enjoyed reasonably amicable relations, the discriminatory treatment of Japanese immigrants in California was a particular sore point for Japan, and by 1905, the United States recognized that a war with Japan over this single issue was a definite possibility, raising concerns that Japan could easily seize the Philippines and Hawai’i due to its superior naval power.[34] The United States and Japan reached the so-called “Gentleman’s Agreement” in 1907, pursuant to which Japan agreed not to issue passports for Japanese to emigrate to California and the U.S. Government agreed to lean on the state of California not to racially discriminate.

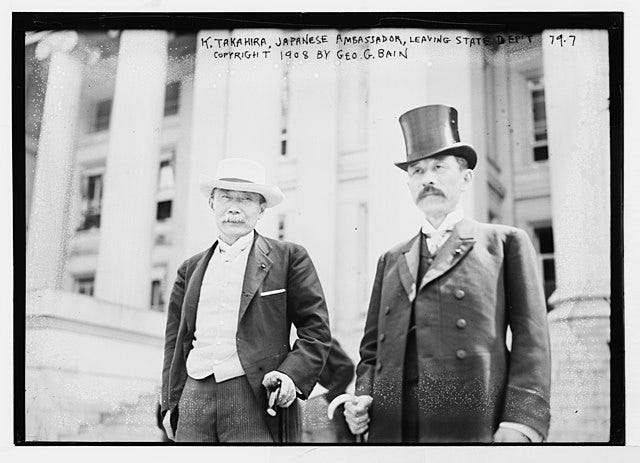

This was followed by the 1908 Root-Takahira Agreement, this time dealing primarily with Japan’s territorial ambitions in Manchuria, which were running up against the United States’ “Open Door” policy in China. Shortly afterwards, President Roosevelt, based on assessments from General Leonard Wood, determined that the Philippines effectively could not be defended from an initial assault by the Japanese, but that the U.S. Pacific fleet, if based in Hawai’i, would serve as not only an effective deterrent to Japanese ambitions in the Pacific, but would protect the West Coast of the United States and serve as an effective launching pad for a retaliatory attack; “without completely destroying the American fleet in Hawai’i, Japan could never be assured that a move to grab the Philippines would yield anything more than a temporary result.”[35] Roosevelt therefore convinced the U.S. Congress to shift plans for building a major naval base from the Philippines to Hawai’i. Pearl Harbor (see, there it is again) offered ideal conditions, and construction began there in earnest in the spring of 1909.

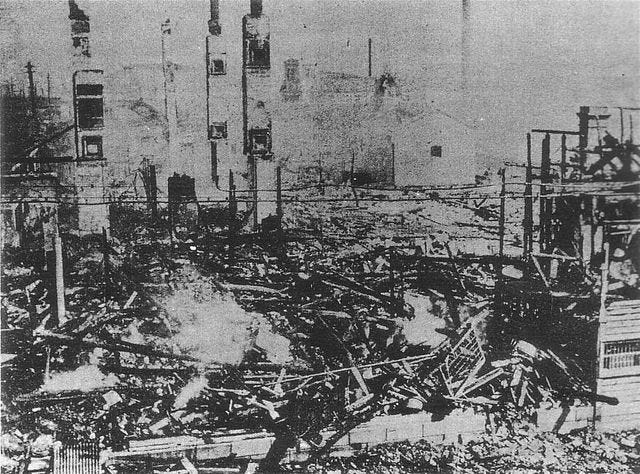

That same year, conditions for Japanese sugar cane laborers on Oahu finally reached a breaking point:

Approximately seven thousand Japanese laborers in all plantations on Oahu abandoned the cane fields for three months just before harvest, and the resulting collective bargaining was on an unprecedented scale. For the first time strikers called for the abolition of racial discrimination in treatment of workers and demanded wage increases to improve living conditions.[36]

Along Come the Filipinos

The fears of a Japanese takeover of Hawai’i were only exacerbated by the influx of Japanese military veterans following the Russo-Japanese War of 1905, with over 30,000 arriving in 1906 alone.[37] But by 1909, the plantation owners now had a new source of labor to use as strikebreakers: Filipinos. Filipinos did not even need to “immigrate,” as the Philippines and Hawai’i were now U.S. territories. The HSPA had begun experimentally to import Filipino laborers in 1906, and by 1910 they had already reached considerable proportions. Between 1907 and 1924, a total of 31,229 Filipino men and 5,790 Filipino women migrated to Hawai’i.[38]

Japan had mostly introduced law-abiding and newspaper-reading farmers of a homogenous culture and language. The Filipinos, by contrast, were linguistically divided between Tagalogs, Cebuanos, and Ilocanos, with no education, no collective sense of community on Hawai’i, no neighborhood stores, and no recreational facilities, with little provided to them on their particularly meager plantation accommodations. Unsurprisingly,

A great part of the population stereotyped them as hotheaded, knife-wielding, overdressed, sex-hungry young men —and there was some truth in the stereotype. Many Islanders probably shared the opinion of HSPA executive secretary John K. Butler that “The majority of the Filipinos have the mentality of 13-year-old children.”…

The friendly Japanese press was apprehensive over the Filipinos’ propensity to violence. Even their devoted supporter George W. Wright referred to the Filipinos as ‘primitive.’ The Filipinos were boxed into their low status. They lacked both capital and a shopkeeping tradition, and the Chinese and Japanese had beat them into the shopkeeping field. Advancement as employees was exceedingly hard to win. Since the Filipino nationality in Hawaii had its share of intelligent, able, ambitious, and sensitive individuals, and since Filipinos have a keen sense of personal dignity, it is probable that a sense of frustration and resentment ran very deep among them.[39]

One Filipino who emerged within this community as a leader was Pablo Manlapit. A more educated Tagalog than the average sugarcane field laborer, Manlapit nonetheless claimed he did not

“possess any academic title—except experience.” Dismissed (he claims) from a timekeeper’s job at Corregidor because of union activities, he came to Hawai’i in February 1910 as one fo the first laborers recruited by the HSPA. Assigned to Kukaiau plantation on Hawai’i island, he was (he claims) soon promoted to be foreman and timekeeper. In 1912 [?] he married Annie Kasby, daughter of a Haole homesteader. In 1913 he was fired (he claims) because of participation in a strike against the lowering of contract rates. In Hilo for about two years, Manlapit worked as a salesman and is first listed in Polk’s Directory as proprietor of a pool parlor. Early in 1913 he launched the first Filipino paper in Hawaii, the short-lived Ang Sandaka (The Sword).

In April 1914 he is noted as organizing and chairing a meeting of unemployed Filipinos in a Hilo park, “but trusted as one who will hold his countrymen in check.” Manlapit moved to Honolulu in February 1915. There he worked as a messenger in a flower store, a tray boy in a pineapple cannery, editor of a briefly revived Ang Sandaka, and a stevedore for McCabe, Hamilton & Renny. On September 26, 1916, during a longshore strike, he was attacked as a scab, knocked down and kicked, and his glasses broken by striking Filipinos. In 1918 and 1919 he is listed as an interpreter at 12 Merchant Street, where he also worked as janitor for attorney William J. Sheldon. Encouraged by Sheldon, he studied law, and on December 19, 1919, he was licensed to practice in the district courts—the only Filipino and non-citizen practitioner in the territory. During this period, he later boasted, “He has been a good mixer, he gain[ed] popularity rapidly—among Filipinos, Hawaiians, Japanese, Chinese and other nationalities.” He became vice president of a Filipino YMCA. With the rank of quartermaster sergeant, he helped bring Filipinos into the National Guard, cannily using it as an employment agency for prospective cooks, house boys, yard boys, and day laborers.[40]

On August 31, 1919, the Filipino Labor Union, such as it was, met in Honolulu and elected Pablo Manlapit as its chair.[41]

Some New and Unsavory Characters

The Japanese community in Hawai’i, on the eve of the sugar strike of 1920, had its own interesting cast of characters, including a growing number of anti-Meiji malcontents that were coming to the attention of the Japanese secret police because of their ties to the global anarchist and socialist movements. In San Francisco in 1907, for example,

an open letter addressed to "Mutsuhito, Emperor of Japan from Anarchists-Terrorists" was posted at the Consulate General of Japan in San Francisco. It began, "We demand the implementation of the principle of assassination." After claiming that the emperor was not a god but, like other humans, an animal who had evolved from apes, it went on, "[The first emperor] Jimmu, the most brutal and inhumane man of his time, ruled as sovereign; under the name of being ruler he relished in every kind of crime and sin; his son followed his example and his grandson after him followed the example of his father; and so on and on down until 1 2 2 generations later." The "open letter" concluded, "Hey you, miserable Mutsuhito. Bombs are all around you, about to explode. Farewell to you."[42]

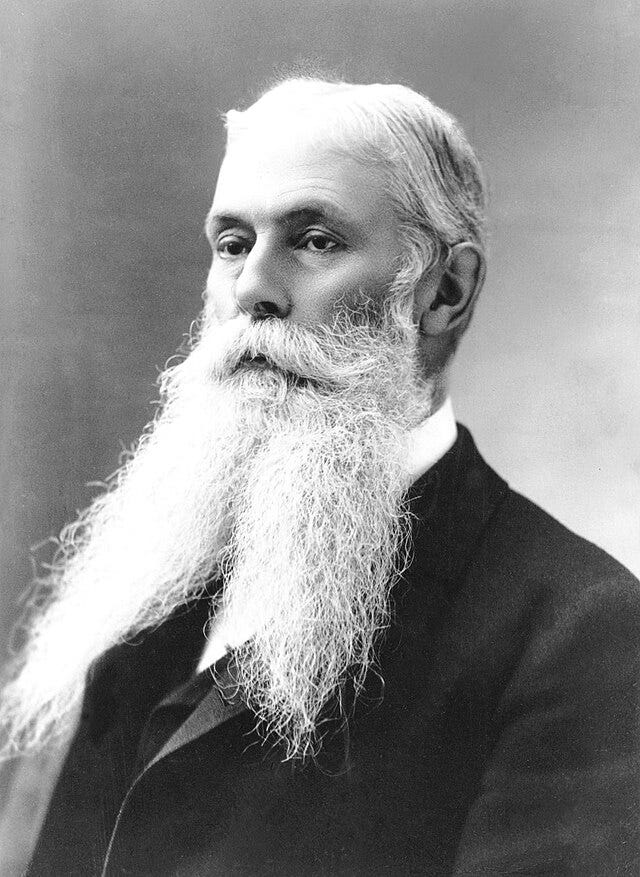

Some of these were the same sort of people now being monitored by the U.S. Bureau of Investigation (BI)’s General Intelligence Division, which had been established by Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer following the bombing of Palmer’s own house on June 2, 1919. (I talked about this incident and the subsequent 1920 “Palmer raids” in this post):

Following Palmer’s fall from grace resulting from his overreach during the “Palmer raids,” the Bureau of Investigation was now headed by J. Edgar Hoover. The BI began compiling a Weekly Summary of Radical Activities, with its California offices carefully tracking the Japanese Federation of Labor and its leaders, who were active on both the mainland and Hawai’i (Hawai’i was not yet under the BI’s jurisdiction). One individual who caught the BI’s attention, particularly after the 1920 Oahu sugar strike, was Noboru (sometimes Takahi) Tsutsumi, who had arrived in Hawai’i in February 1918 initially to serve as the principal of a local Japanese language school. Later BI reports about Tsutsumi out of Los Angeles described him as

a very dangerous agitator and a Radical Socialist. He is highly educated in Japanese, being a graduate of the Imperial University at Tokio [mistake for Kyoto Imperial University]...He is a very fluent speaker, very radical in his views. The laborers at present worship him like a god and believe whatever he tells them…Tsutsumi, in a speech, told the Japanese that if they did not win he would commit Hari Kiri, that it would be unpardonable sin if the Japanese did not win and that in that event he would suicide.[43]

Tsutsumi, whose attention quickly turned while in Hawai’i from his day job as a school principal to the plight of the sugar cane workers, was indeed of a more decidedly radical bent than many of the local Japanese community leaders. The Japanese Association in Honolulu was “dominated by upscale shop owners, school principals, religious leaders, newspapermen, and other professionals,” who “thought of themselves as the elite within the Japanese community.” The Plantation Labor Supporters’ Association that they helped form, purportedly to advocate for the field laborers against the HSPA, was in fact “made up of representatives from various occupational groups, including the craftsmen's union, the automobile association union, the barbers' association, the fisheries association, the pawnshop, cleaner, and tailor industries, the young men's association, and various prefectural associations. Of the twenty officers of the supporters' association, nine were newspapermen working for Japanese language papers.”[44] These people weren’t quite sure what to make of Tsutsumi, whose education was superior to their own and who

had never made the round of greetings to the Japanese-language newspapers, considered customary for anyone seeking to do anything in Honolulu. It was Tsutsumi, moreover, who had warned against the involvement of the Japanese newspapermen in the wage increase movement and insisted that it should be a labor movement with "true laborers" as its members.[45]

Tsutsumi instead became affiliated with the Japanese Federation of Labor when it was stood up in December 1919. The Federation was much more strident in opposing the HSPA than were the Plantation Labor Supporters’ Association. However, many of the other Federation’s leaders were not above self-enrichment, or at least a form of conspicuous consumption that could rankle:

At a time when the typical laborer could scarcely afford a 10-cent bowl of noodles at a cheap eatery, federation staff members held meetings at restaurants. Ryokin Toyohira, a reporter for the Nippu jiji, recalled, "I think Tsutsumi and the other leaders of the Federation were earnest, but it was a collection of many kinds of people and they had increased in number, so it can't be said for certain that there were no bad elements. The inn where the Federation leaders stayed included a restaurant where they held their meetings and consultations, so the Hawaii hochi and others jibed at the drinking and eating.[46]

There were also people with an unspecified association with the Federation whom the latter appear to have employed as their “muscle” or “man Friday”; chief among them, Seigo Kondo, a brawny, thick-necked owner of both a pool hall and a fishery at Pearl Harbor, who was intermittently described as either a “local boss,” “security,” or some sort of “troubleshooter” between striking laborers and scabs; he would later be accused of paying hush money on behalf of the Federation in connection with the bombing.[47] If there was dirty business to be done, Kondo could be counted on to find recruits like Junji Matsumoto, who had come to Hawai’i at the age of 16 to work in the sugar cane fields and could often stay at a job no more than 6 months before being fired due to physical altercations, including with Juzaburo Sakamaki, the plantation interpreter. Matsumoto was later employed by a Foundation member collecting subscription fees for a newsletter.[48]

With Japanese and Filipino sugar cane laborers in Hawai’i earning 77 cents a day, while the price of Japanese imported rice was doubling due to shortages so bad that they had prompted “rice riots” in 1918 all across Japan,[49] and this cast of characters in charge, what could possibly go wrong?

[1] “Chronicling America: Historic Newspapers from Hawaiʻi and the U.S.: Sugar Industry,” University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, available at https://guides.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/c.php?g=105252&p=687131 (viewed April 5, 2025).

[2] Radhika Mongia, Indian Migration and Empire: A Colonial Genealogy of the Modern State (Duke University Press, 2018), at 23.

[3] Sara Kehaulani Goo, “After 200 Years, Hawaiians Making a Comeback,” Pew Research Center, April 6, 2015, available at https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2015/04/06/native-hawaiian-population/ (viewed April 5, 2025).

[4] Interestingly, the collaboration between Hawai’ian ruling monarchs and white mariners dates back to shortly after James Cook’s landing. See Peter T. Young, “Kamehameha’s Haoles,” Images of Old Hawai’i, May 28, 2020, available at https://imagesofoldhawaii.com/kamehamehas-haoles/ (viewed April 8, 2025).

[5] Masayo Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 14.

[6] Alan Takeo Moriyama, Imingaisha: Japanese Emigration Companies 1894-1908 (University of Hawaii Press, 1985), at 92.

[7] Christen T. Sasaki, Pacific Confluence: Fighting Over the Nation in Nineteenth Century Hawai’i (University of California Press: 2022), at 84.

[8] Michael C. DeMattos, Race, Class and Identity Formation Among the Portuguese of Hawai’i, 1880-1930, Ph.D dissertation submitted to the University of Hawai’i at Manoa, May 2022, at 15.

[9] Peter Carlisle, “The Last Luna’s Memories of Hawaii’s Plantation Era,” Honolulu Civil Beat, December 23, 2014, available at https://www.civilbeat.org/2014/12/peter-carlisle-the-last-lunas-memories-of-hawaiis-plantation-era/ (viewed April 7, 2025).

[10] Masayo Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 14.

[11] Quoted in Gary Y. Okihiro, Cane Fires: The Anti-Japanese Movement in Hawaii 1865-1945 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1991), at 20, available at https://archive.org/details/canefiresantijap00okih/page/n9/mode/2up (viewed April 8, 2025).

[12] Alan Takeo Moriyama, Imingaisha: Japanese Emigration Companies 1894-1908 (University of Hawaii Press, 1985), at 5.

[13] Masaji Marumoto, “Vignette of Early Hawaii-Japan Relations: Highlights of King Kalakaua’s Sojourn in Japan on His Trip Around the World As Recorded in His Personal Diary,” Hawaiian Journal of History, Volume 10, 1976, available at https://evols.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/items/e5c0e6ba-bd72-42ac-858b-460c7a7ebb8b

(viewed April 8, 2025).

[14] Christen T. Sasaki, Pacific Confluence: Fighting Over the Nation in Nineteenth Century Hawai’i (University of California Press: 2022), at 79-82.

[15] Masayo Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 15.

[16] Alan Takeo Moriyama, Imingaisha: Japanese Emigration Companies 1894-1908 (University of Hawaii Press, 1985), at 109-10.

[17] Quoted in Masayo Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 21.

[18] Alan Takeo Moriyama, Imingaisha: Japanese Emigration Companies 1894-1908 (University of Hawaii Press, 1985), at 100.

[19] “About Us,” Consulate General of Japan in Honolulu (undated), available at https://www.honolulu.us.emb-japan.go.jp/itpr_en/ryoujikan_history_en.html (viewed April 9, 2025).

[20] Alan Takeo Moriyama, Imingaisha: Japanese Emigration Companies 1894-1908 (University of Hawaii Press, 1985), at 107.

[21] Alan Takeo Moriyama, Imingaisha: Japanese Emigration Companies 1894-1908 (University of Hawaii Press, 1985), at 101.

[22] Richard J. Samuels, Special Duty: A History of the Japanese Intelligence Community (Cornell University Press, 2019), at 35.

[23] Richard J. Samuels, Special Duty: A History of the Japanese Intelligence Community, at 43.

[24] Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard and Intermediate Maintenance Facility, “The History of Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard” (undated), available at https://www.navsea.navy.mil/Home/Shipyards/PHNSY-IMF/A-Proud-History/ (viewed April 9, 2025).

[25] Eric T.L. Love, at 73-74, 116-17 (describing how a white minority established a provisional government in Hawai’i and purposefully excluded Asian males, prompting two to three thousand Hawai’ian royalists to protest the constitutional convention); and at 139 (describing how Hawai’ian president Sanford Dole counted 15,000 individuals of mixed Portuguese ancestry on Hawai’i as “white”).

[26] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 82.

[27] Alan Takeo Moriyama, Imingaisha: Japanese Emigration Companies 1894-1908, at 49.

[28] Alan Takeo Moriyama, Imingaisha: Japanese Emigration Companies 1894-1908, at 56.

[29] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 103.

[30] Alan Takeo Moriyama, Imingaisha: Japanese Emigration Companies 1894-1908 (University of Hawaii Press, 1985), at 103-04.

[31] Alan Takeo Moriyama, Imingaisha: Japanese Emigration Companies 1894-1908 (University of Hawaii Press, 1985), at 106.

[32] See Eric T.L. Love, at 145 (describing how, by the time the U.S. Senate Committee on Foreign Relations was deliberating over a joint resolution to annex Hawai’i on March 16, 1898, “[t]he Japanese threat had been moved to the top of the list of the committee’s ‘reasons in favor of the annexation of Hawaii,’ head of justifications based on military and strategic advantage and the role they would play in advancing American trade in East Asia.”). By this point, the Chinese population in Hawai’i was seen as “relatively powerless and unthreatening compared to the “aggressive Japanese,” evincing “little desire to use the ballot, from which they are excluded.” Id. at 146. See also Id., at 153 (noting that President McKinley warned Senator George Frisbie Hoar that “Japan has her eye on [the Hawai’ian islands. Her people are crowding in there. I am satisfied that they do not go there voluntarily, as ordinary immigrants, but that Japan is pressing them in there in order to get possession before anybody can interfere.”).

[33] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 19. A small strike among Japanese laborers broke out on the Olaa plantation in 1905, following the death of a laborer who had taken medicine prescribed for him by the plantation doctors (plantation doctors’ central function being figuring out who was feigning illness, rather than treating patients). Id. at 18-19.

[34] Choi Jeong-Soo, “The Russo-Japanese War and the Root-Takahira Agreement,” International Journal of Korean History (Vol. 7 February 2005), 133-63, at 138, available at https://ijkh.khistory.org/upload/pdf/7_06.pdf (viewed April 12, 2025).

[35] Choi Jeong-Soo, “The Russo-Japanese War and the Root-Takahira Agreement,” International Journal of Korean History (Vol. 7 February 2005), 133-63, at 141.

[36] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 19.

[37] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 20-21.

[38] John E. Reinecke, The Filipino Piecemeal Sugar Strike of 1924-1925 (University of Hawai’i Press, 1996), at 2.

[39] John E. Reinecke, The Filipino Piecemeal Sugar Strike of 1924-1925 (University of Hawai’i Press, 1996), at 3-4.

[40] John E. Reinecke, The Filipino Piecemeal Sugar Strike of 1924-1925 (University of Hawai’i Press, 1996), at 4-5.

[41] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 48.

[42] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 22.

[43] National Archives, Investigative Case Files of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, January 28, 1941, report on Japanese Affairs (Honolulu and Hawaii Islands); referring to Los Angeles Weekly Intelligence Report for January 13, 1921, pp. 26, 27, 28. Quoted in Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 27-28.

[44] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 49.

[45] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 53.

[46] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 97.

[47] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 97.

[48] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 161-62.

[49] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 44-46.

I've read through part 3 and I'm finding it interesting. I'm looking forward to you tying it together. I thought you might be interested in (or hate me for suggesting) taking a look at "Captive Paradise, A History of Hawaii," by James L. Haley. It provides more nuisance and background related to the importation of foreign labor and Hawaii's relations with foreign governments. "Captive Paradise" covers the period of time between the death of Capt Cook in 1779 through the U.S. Annexation in 1898, through the lens of the impact of missionaries and the end of Hawaiian cultural practices that adoption of Christianity by the Hawaiian Monarchy brought about. Chapter 13 is "Mountains of Sugar" and Chapter 14 ends with an ominous note about the new king and hisbsugar creditors. However, overall, the book provides a lot of context of how after King Kamehameha I dies, his alcoholic son and various queen regents, are willing to make trade deals and be influenced by the Japanese government (and ultimately are overtaken by U.S. business interests) because they are financing their personal debts, making deals to obtain royal succession, or appeasing anger over banning traditional practices to adopt Christianity. It's a great read as well.