The Filing Cabinet and the Surveillance State

Part 2 of (at least) 3 on the history of identity intelligence

In my last post—

which my wife said was too long (!!)—I promised that in the next post I was going to talk about early 20th century innovations in “photography, fingerprinting, library science, and, of all things, the filing cabinet.” But if I tried to hit all of those in Part 2, the below post would have been even longer.

So, this post is just going to focus (mostly) on those last two items: library science and the filing cabinet. Stay with me. It’s more exciting than you think, not to mention quite a bit creepy.

Here’s the thing with today’s post and why it also got longer than I expected (eventually becoming Part 2 of 3 rather than Part 2 of 2): I had no idea when I started researching for it that I was going to have to learn something about the history of American medicine and public health, by way of our history of immigration policy. If you’ve been wondering why some Americans seem to react so strongly and negatively to vaccines and other pandemic-related public health measures, or can’t understand why everyone in the United States does not regard Health and Human Services Secretary RFK Jr. as a crazy person, then you definitely need to read this. And if you are one of the Americans who does react strongly and negatively to mandatory vaccines and our standardized public health regime, you should also read it and learn where it comes from.

What is the purpose of a passport, exactly? Is it to control immigration, or emigration? Is it a means for Westphalian nation-states to exert control over movement both into and out of their territories? Is it just a means of identification? Is it proof of citizenship or nationality, or is it something that requires proof of citizenship or nationality in order to grant freedom of movement? These were some of the unsettled questions that were brought to the forefront by Italy’s passport law of 1901.

Italy was at that time still a relatively new Westphalian nation-state and striving for greater respect from other European powers. For many centuries after the collapse of the Roman Empire, the Italian peninsula was ruled by various small kingdoms and city-states, then was governed for a time by the Spanish Habsburgs, until they were defeated by Napoleon. After Napoleon himself was defeated in 1815, the Austrian Habsburgs took over, which was followed by a series of insurrections in an era called the Risorgimento, which finally resulted in the Kingdom of Italy in 1870, with Rome as its capital.

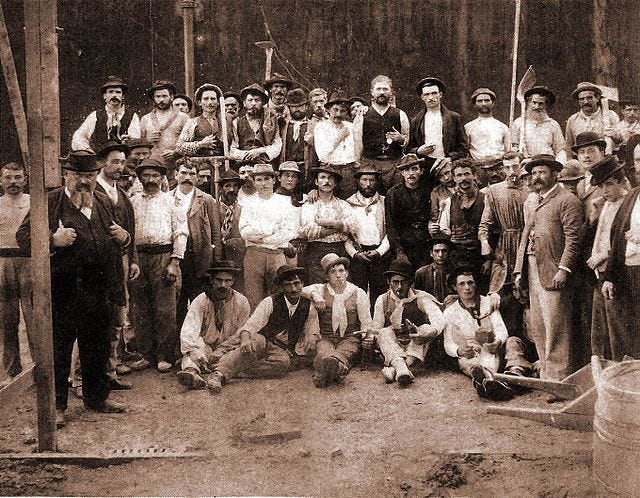

During the Risorgimento, approximately 25,000 northern Italians immigrated to the United States, fleeing the conflict. Afterwards, a total of 4 million Italians, mostly landless peasants from southern Italy and Sicily—essentially the Italian version of “coolie” labor—came to the United States between 1880 and 1920, many of them single men seeking to simply make money for a few years before returning to their families.[1] These Italians were not always well-received in America; in fact, many white Anglo-Saxon Protestant Americans, when confronted with so many dark-skinned Italian peasants, began to wonder if their extreme animosity towards the Chinese had been somewhat misdirected.[2]

To the Italian aristocracy, exporting their landless peasants was a much more desirable outcome than enacting serious land reform; in fact, one of the primary reasons Italy eventually invaded Libya in 1911 was to steal someone else’s land so that their “excess” population had somewhere else to go. In 1896, southern Italian economist and future prime minister Francesco Nitti opined that emigration to the United States was a “powerful safety valve against class hatreds.”[3] Accordingly, Italian lawmakers became concerned that, between 1899 and 1900, more than 1200 Italian emigrants had been refused entry into American ports, many based on the likelihood that they would become a public charge. The passport law of 1901 therefore required that trans-Atlantic travelers be in possession of a passport before purchasing their steamer tickets, that passports be delivered within 24 hours of a legitimate request, and that the travelers also obtain a medical certificate prior to departure attesting to their general state of health.[4]

The Italian officials’ concerns were well placed. With the Immigration Act of 1891, the U.S. federal government had taken control of U.S. borders away from the U.S. states and had indeed added a few new categories of “excludable” aliens, on top of the Chinese laborers and persons likely to become a public charge, to include “persons suffering from a loathsome or a dangerous contagious disease.”[5] The Act created a Superintendent of Immigration within the Treasury Department and provided that any ship arriving at any U.S. port containing alien immigrants would be boarded by inspection officers, who would inspect each and every alien listed on the ship’s manifest, with a medical examination to be carried out by the Marine Hospital Service.[6] The Marine Hospital Service, which had been created in 1871 out of a consolidation of hospitals that since 1798 had been serving merchant marines (not the U.S. Marines), was led by the Surgeon General and had gradually accreted to itself a number of duties and authorities related to domestic and foreign quarantines. It would be rebranded as the U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) in 1912.[7]

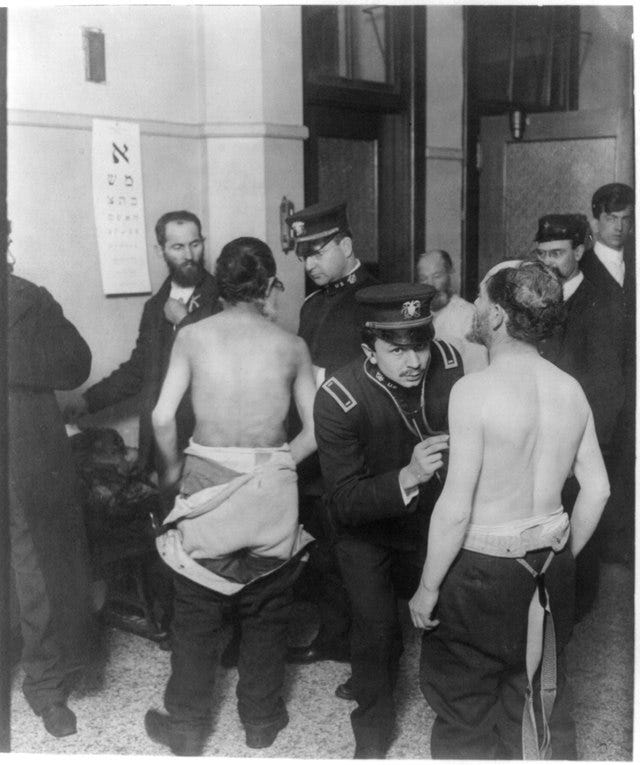

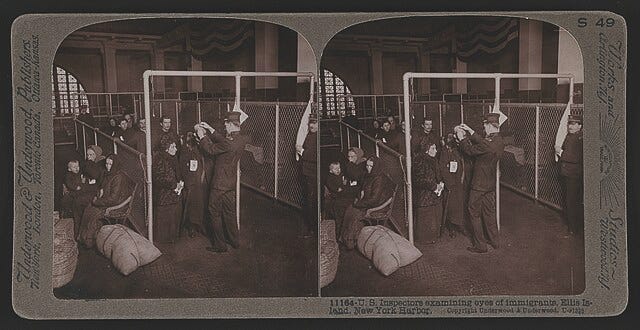

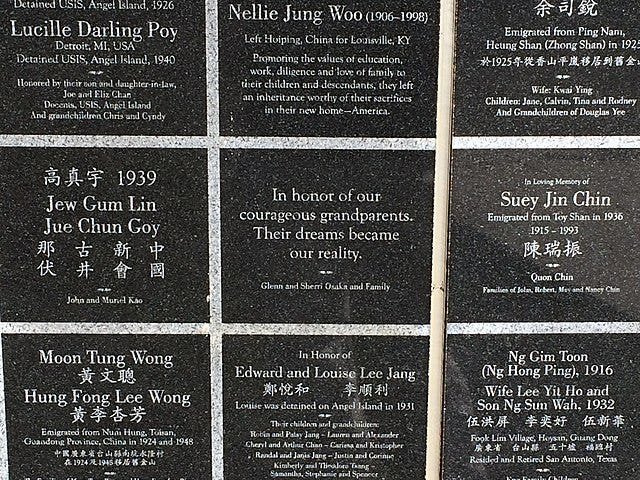

After the immigrant processing facility at Ellis Island was opened on January 1, 1892, this facility, through which 70 percent of all immigrants entered the United States, largely set the standard for the others. Inspection officers and medical examiners would board the ships together and examine the first- and second-class passengers as the ship approached the harbor. The passengers in third class and steerage were instead transferred to Ellis Island by barge, after which they were observed by medical examiners as they slowly made their way down a series of gated passageways, typically hauling heavy baggage with them. The examiners surveyed them for major and obvious diseases, turning their eyelids back to check for trachoma, and then, as appropriate, wrote chalk marks on the immigrants’ clothing: “C” for a possible eye condition, “S” for senility, “X” for insanity, and “EX” indicating that they should be examined further.

About 15 to 20 percent of all arrivals received some form of chalk mark and were pulled off “the line” and into an examination room. There, they were examined and held for as long as necessary for the physicians to make an accurate diagnosis. Some were confined, sometimes for years, in the isolation units of the southernmost wing of Ellis Island, where some even received medical treatment. If they were issued a “medical certificate,” however, they were denied entry to the United States, although they could appeal the determination to an Immigration Service Board of Inquiry, where three Immigration Service officers asked questions mostly about the immigrant’s occupation, finances, and family residing in the United States (which suggests some conceptual overlap between medical determinations of ineligibility and the assessed likelihood of the person becoming a public charge).[8]

In practice, the medical examiners were given broad discretion to discharge their functions, and the examination procedures worked very differently on the Pacific Coast and the southern U.S. border, through which non-Europeans were more likely to immigrate:

“At Texas border stations, PHS medical inspectors stripped, showered, disinfected, searched for lice, and physically examined large groups of immigrants. All second- and third-class Asians immigrants arriving in San Francisco endured a physical exam similar to that conducted along the Mexican border in addition to routine laboratory testing for parasitic infection, which required detention at Angel Island for one or more days. Disease, health officials argued, was not so easily ‘read’ in the ‘inscrutable’ Asians, particularly the Chinese.”[9]

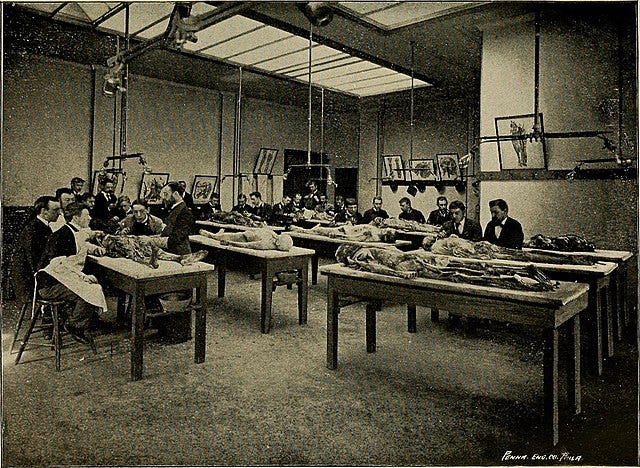

Nonetheless, the standardization of medical practice that resulted from the immigrant medical examinations, mostly at Ellis Island, had a “startling” ripple effect through the American medical community as a whole. American medical education had been somewhat insulated from the “germ theory” of illness that arose from the discoveries of European scientists like Lister and Pasteur; only those U.S.-based doctors who travelled to mostly German clinics in the 1870s were starting to come back to the United States convinced of this facially implausible theory that “invisible animalcules were the cause of so much disease and suffering.” In fact, prior to the 1880s,

“no one group of medical practitioners could claim clear therapeutic superiority over any other, and 19th century Americans chose their cures with as much freedom as they chose their elected officials. Americans guarded their ‘medical freedom’ as jealously as their more traditional freedoms of speech and religion because, somewhat perversely, they regarded the proliferating and contradictory therapeutics of the era as yet another example of free choice in ‘our own free Republican America.’”[10] But the physicians of the Marine Hospital Service were the undisputed champions of the “germ theory,” and even before they took on immigration-related duties, they were busy imposing public health standards on the urban poor. When in 1912 Congress created the Public Health Service out of this same group of physicians, it effectively overcame a yearslong campaign by the National League of Medical Freedom against ‘any one system of healing…us[ing] the government…to enforce its theories and opinions upon citizens.’”[11]

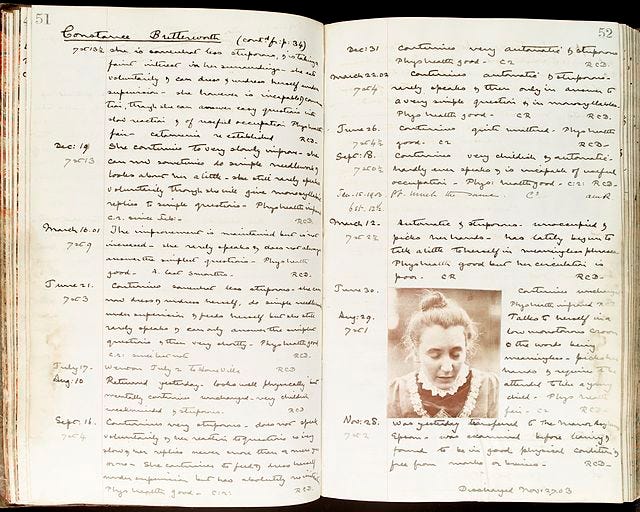

The standardization of medical practice occurred alongside a similar effort with respect to patient records. Starting in the late 19th century, Harvard Medical School—inspired by the “case histories” being compiled over at the Harvard Law School—began developing clinical records templates in the late 19th century, complete with empty fields to enter family history, patient habits, blood and urine test results, etc. Hospitals were at the same time making their own significant transition from handwritten to standardized typescript records.[12]

The importance of templated forms for large-scale PII collection and analysis is something I discussed here:

Specifically, I recounted how Major Ralph van Deman successfully turned around the U.S. Army’s counterinsurgency war in the Philippines in 1901 by compiling information cards on every influential Filipino, a precursor to what the U.S. counterterrorism infrastructure would refer to today colloquially as “baseball cards.” Hundreds of U.S. Army posts throughout the Philippines filled out the card template, which was called a Descriptive Cards of Inhabitants, and sent them to Van Deman’s Division of Military Information (DMI), whose clerks then carefully transcribed them into indexed, alphabetical rosters for each military zone. The DMI then disseminated intelligence back out to the field and the civil police in a variety of formats, such as daily summaries or operational bulletins.[13]

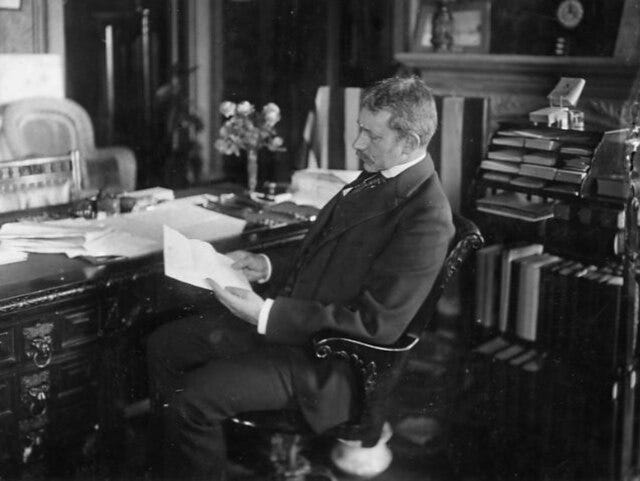

It was all well and good to have standardized forms for individual records, but how could such records be efficiently stored and retrieved? While Van Deman’s clerks painstakingly transcribed the cards into lists, hospitals and medical schools tended to maintain patient files in large, bound book volumes or ledgers. Solo medical practitioners making house calls kept their own personal case book, day book or diary.[14] When Elihu Root became Secretary of State in 1905, he asked for a handful of letters and instead, to his exasperation, promptly found several large bound volumes dropped on his desk, as State Department correspondence was also at that time kept in bound press books or copy books, in chronological order, with limited indexing.[15]

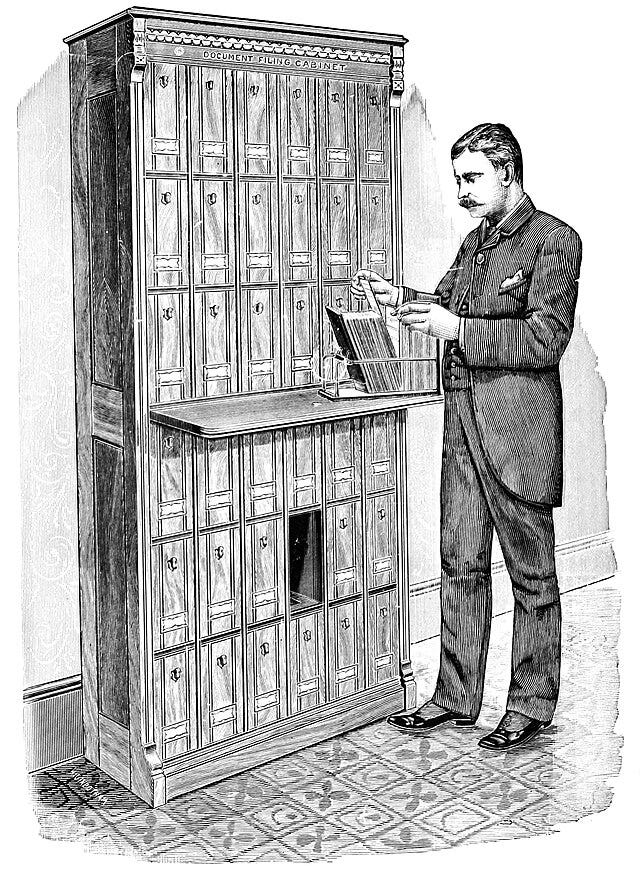

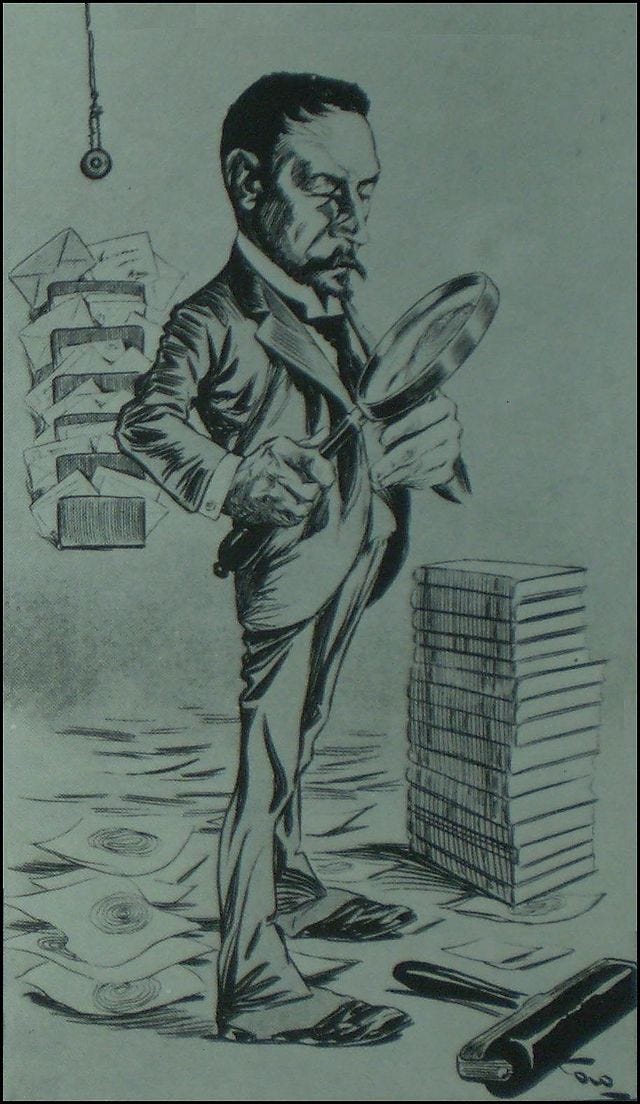

Root felt as if he were “a man trying to conduct the business of a large metropolitan law firm in the office of a village squire.” [16] This is because he had recently re-joined government from a private law firm, and the U.S. commercial sector was already far ahead of many government agencies with regard to a key innovation that was revolutionizing information management: the filing cabinet.

The commercial sector already had been experimenting with storing papers in loose leaf binders as early as the 1890s, but the problem they were running into was that courts were not sure whether these were acceptable as evidence. After all, a book was at that time defined by its binding, and “the structural integrity of a bound book had become accepted as proof that the accounts contained within it were original records and, therefore, had been created ‘at or about the time of the transaction.’”[17] As Craig Robertson notes in his surprisingly scintillating history of the filing cabinet:

“The appearance of the loose-leaf ledger illustrated the extent to which legal reasoning had linked material wholeness and moral soundness, such that the former was interpreted as evidence of the latter. In the creation of records, bound paper offered evidence of moral integrity; legal reasoning interpreted it as offering freedom from moral corruption. If a binding could not prevent a page being removed, it would likely provide evidence of that removal or absence through residual paper in the gutter or a gap in page numbers. The probable appearance of this evidence was viewed as a further deterrent. In contrast, loose paper too easily invited the presumption of loose behavior. That the leaves were loose, and thus easily attached and detached, raised doubt and suspicion about what could happen to individual sheets of paper.”[18]

But a manila folder or a hanging folder inside a filing cabinet brought the commercial and legal community much farther along in their acceptance of a “file” as offering the same degree of integrity. It certainly helped that such folders could store loose papers without damaging them, as typical 19th century storage solutions for loose paper included primary wooden pigeon holes and metal spikes. The manila folder also could easily accommodate different sizes of paper, an important feature, as the United States would not settle on the standard 8.5 x 11-inch paper size until the late 1920s, with Europe of course developing a slightly different standard, 210 by 297 millimeters, based on the metric system.[19]

The filing cabinet gained even more widespread social acceptance thanks to early 20th century innovations in steel manufacturing that rendered steel a pourable fluid. By 1910, steel had become the material of choice for modular filing cabinets, with advertising emphasizing the production process, touting the “integrity” of steel, and making loving comparisons between the verticality of steel filing cabinets and that other great symbol of 20th century American progress: the skyscraper.[20] Steel also enabled further innovations to support the weight of files through “frictionless extension slides” for the drawers, with ball bearings incorporated to ensure smoothness of movement, and spring-loaded compressors to keep files vertical in partially-empty drawers.[21]

Modular, steel filing cabinets were ripe to achieve widespread commercial and legal acceptance, arriving as they did amid evolving business doctrines about the very purpose of an office, of managers, and of information:

“The standardization of filing systems began with cabinets, drawers, and folders designed to store different sizes of paper and cards. However, the ‘system’ that office equipment companies were trying to sell incorporated other technologies that enhanced the granularity of modern storage practices, including index systems, charge systems, cross- reference systems, and systems for transferring old documents into storage, usually at the end of the financial year (what is now called records retention). These additions furthered the process of naturalizing a specific relationship to information, an instrumental relationship to a discrete object. The aim was to create information sized to the smallest functional detail, but in such a way that managers could easily coordinate bits of information and not lose sight of the big picture that was the business or corporation.”[22]

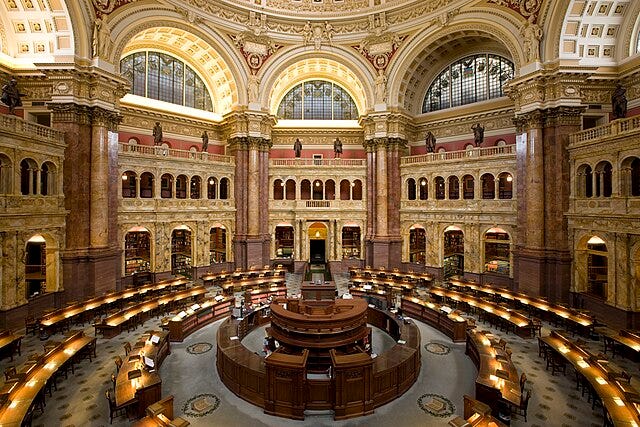

A similar revolution was occurring, albeit with wooden filing cabinets, in, of all places, the library—specifically, the U.S. Library of Congress. Initially conceived of simply to serve Congress, it had seen an explosive growth in its book collection courtesy of the Copyright Act of 1870 (also known as the Patent Act), which required any person claiming a copyright in a published book to mail two copies of the book to the Library of Congress.[23] By 1876 the Library’s holdings had already tripled in size to 300,000 volumes, and in 1897 its current palatial location at 10 First Street, across from the U.S. Capitol, was opened ceremoniously to the public.

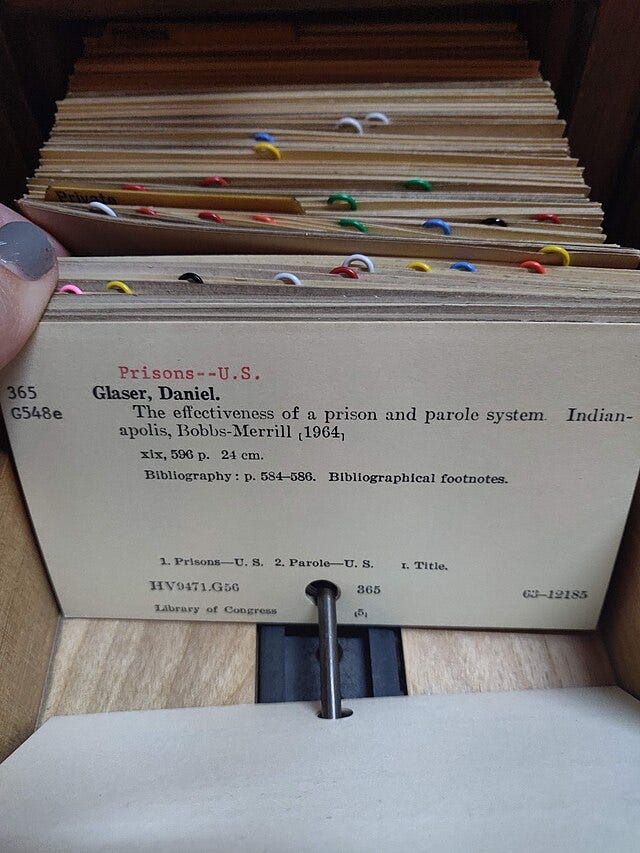

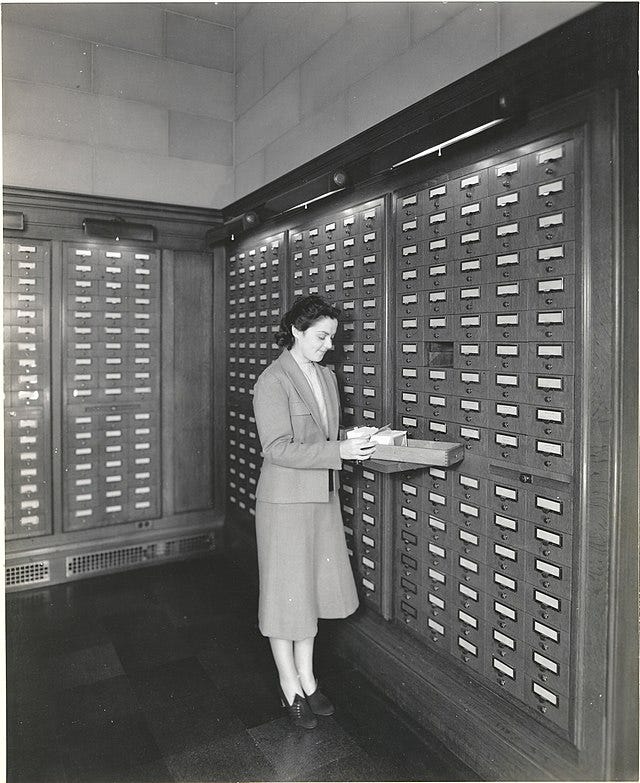

With its transition from a library for Congress to its new role as essentially the nation’s library, many great luminaries from the American Library Association, including ALA President Melvil Dewey, testified before Congress as to the importance of a modernized and well-made catalog to serve the public.[24] Starting in 1899, under the dynamic leadership of George Herbert Putnam, the Library of Congress threw itself into the task of printing catalog cards with wild abandon, establishing a Government Printing Office (GPO) facility inside the library and printing millions of standardized cards, not only for the Library of Congress’ holdings but for hundreds of libraries across the country that were willing to pay for the cards at a 10% markup to conform to the new de facto national standard.[25]

Other parts of the federal government were left to catch up to the Library, not to mention the commercial sector’s now mainstream standards of efficiency and records management. By the end of the 19th century, the federal government was running deficits and yet lacked a comprehensive understanding of its overall budget. Accordingly, in 1910 President Taft appointed a Commission on Economy and Efficiency, which resulted in the first ever presidential budget. The Commission also ended up spending a considerable amount of time studying the filing systems then in wide commercial use, as well as changes that had already been made at the State Department at the insistence of Elihu Root. It made two key recommendations to government agencies: vertical files in filing cabinets and a decimal filing system that organized papers by subject.[26] Mevil Dewey, most fortuitously, happened to be in the business of selling both.

All of this innovation still did not entirely address the challenges faced by U.S. immigration authorities, particularly on the West Coast, where customs inspectors regularly complained about “the great similarity among Chinese in the color of their hair, eyes and skin.” In the 1880s, unaware of the Bertillon method, authorities had experimented with efforts to at least record marks, scars, and height, but Bertillonage requires rigorous technique, and without it, even height measurements suffered from inconsistency, as some inspectors measured the height of their subjects with their shoes on, or with “their pigtails curled on top of their heads.” [27]

In 1883 Detective Harry Morse was able to gain some traction within the Treasury Department for the idea of taking thumb prints from Chinese immigrants seeking “return certificates,” as such an identifier was seen as both more accurate and more economical than the facial photograph. But the science of fingerprinting was still inchoate, and eventually Geary’s amendments to immigration law rendered the issue moot, as Congress simply barred all Chinese immigrant laborers from entering the United States and the “return certificates” were no longer necessary. It is not at all clear where Morse even got the idea; it might have been from the Chinese themselves, as fingerprints had been used as signatures in China for centuries, and “Chinese prostitutes’ indenture contracts found in the United States dating from as early as 1886—and perhaps earlier—were signed with thumbprints.”[28]

An Argentinean criminologist named Juan Vucetich was at that time also experimenting with fingerprinting as a more scalable technique for tracking large populations of undesirable immigrants, as Argentina was also at that time concerned about maintaining or even further whitening its already-quite-white population. Immigration had become a “major social issue” in Argentina starting in the 1880s, with 43 percent of its immigrants coming from Italy, causing a faster rate of urban growth in Buenos Aires than in New York City, and statistics showing not only an increase in crime but a steadily increasing percentage of immigrants among those arrested.

Accordingly, even the Argentinean nativists of Italian or Spanish descent became concerned about the influx of Southern and Eastern Europeans, whom they considered racially inferior to Anglo-Saxons (ironically, Vucetich himself was an immigrant from Croatia).[29] But Vucetich’s methods were never translated from their original Spanish, and it would take a few more decades for fingerprinting science in the English-speaking world to coalesce around a Scotland Yard practice that became known as the Henry Classification Method.

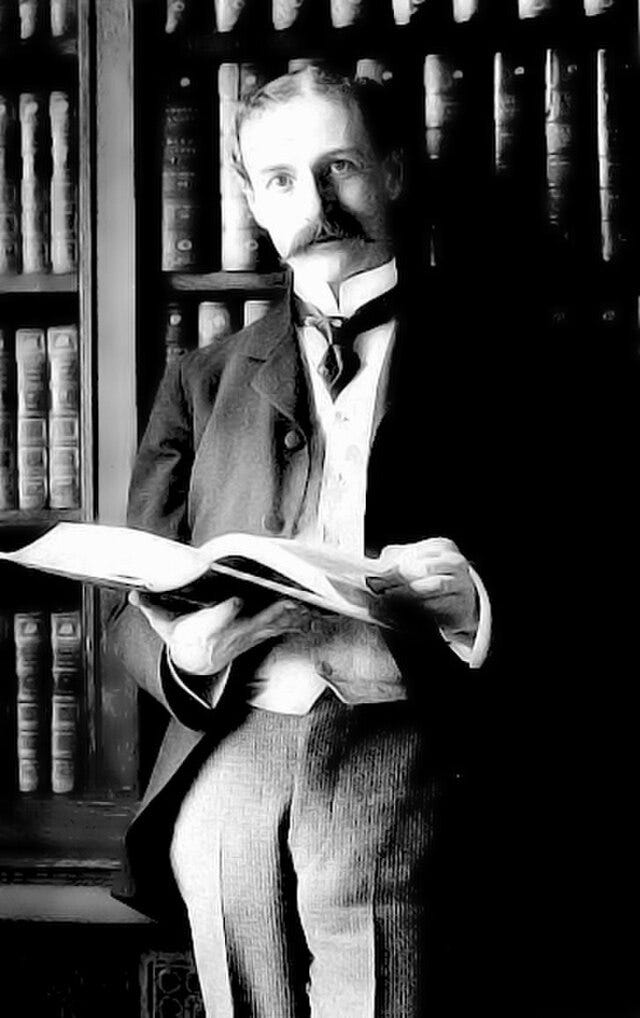

Meanwhile, Herbert Putnam, who turned out to be the longest-serving Librarian of Congress in its storied history, was still there in October 1913 when a young graduate of George Washington University named John Edgar Hoover got a job in the library’s “order division,” through an uncle who socialized with Putnam at the Cosmos Club. In a job that many might have perceived as drudgery, there was nonetheless “a certain frisson” that came with the challenge of sorting information under Putnam’s innovative methods and forceful leadership. Hoover took to the task of filing the new materials that arrived at the library every day with great enthusiasm, the other clerks urging him to slow down with all of his sorting and classifying. Not only did Hoover position himself at the cutting edge of the era’s information technology, at the Library he learned some valuable lifelong lessons from Putnam on how to run a government bureaucracy:

“As a public figure, Putnam was extraordinarily sensitive to the library’s image, developing elaborate codes of behavior for how employees ought to interact with congressman and citizens alike. He enforced these rules through a blizzard of ‘General Orders,’ infamous memos outlining everything from proper cataloguing procedure to how to greet patrons. Meticulous to a fault, he exercised personal control over staff, budgets, communications, and ordering for the library collections—in short, everything that mattered. When he found even the slightest error by a clerk or librarian, he was famous for tirades of such ‘precision and eloquence’ that they ‘would arrest circulation and scar the flesh’ of his employees. To the degree he was willing to delegate, he insisted on being able to choose his own staff and fought to keep them outside civil service rules, established in the 1880s to reduce partisan influence over government staffing. The civil service merit-testing system, in which bosses were supposed to accept all eligible comers, reduced employers’ hiring discretion—presumably the reason Putnam rejected it.

“Putnam’s methods yielded a mixed reputation in Washington. Some viewed him as a truly inspiring leader, brimming with ‘the energy and nerve that could ensure success.’ Others saw him as a tyrant and megalomaniac. Hoover went on to replicate many of Putnam’s best and worst qualities.”[30]

(cont’d)

[1] U.S. Library of Congress, “The Great Arrival,” available at https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/immigration/italian/the-great-arrival/ (viewed February 23, 2024).

[2] Mary Roberts Coolidge, Chinese Immigration (New York, Holt and Company, 1909), at 235-36.

[3] John Torpey, The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State (Cambridge University Press, 1st Ed. 1999), at 128.

[4] John Torpey, The Invention of the Passport: Surveillance, Citizenship and the State (Cambridge University Press, 1st Ed. 1999), at 127-28.

[5] An Act in amendment to the various acts relative to immigration and the importation of aliens under contract or agreement to perform labor, March 3, 1891, Chapter 551, 26 Stat. 1084 1887-1981, 51st Congress, Sess. II, p. 1084, available at https://web.archive.org/web/20160405161336/http://library.uwb.edu/static/USimmigration/26%20stat%201084.pdf (viewed February 24, 2025).

[6] Id. at 1085.

[7] See generally Annual Report of the Supervising Surgeon of the Marine Hospital Service of the United Staes for the Fiscal Year 1873 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1873); see also Records of the Public Health Service, U.S. National Archives, at https://www.archives.gov/research/guide-fed-records/groups/090.html (viewed February 24, 2025).

[8] Allison Bateman House, MA, MPH and Amy Fairchild, PhD, MPH, “Medical Examination of Immigrants at Ellis Island,” History of Medicine, April 2008, American Medical Association Journal of Ethics, available at https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/medical-examination-immigrants-ellis-island/2008-04 (viewed February 25, 2025).

[9] Allison Bateman House, MA, MPH and Amy Fairchild, PhD, MPH, “Medical Examination of Immigrants at Ellis Island,” History of Medicine, April 2008, American Medical Association Journal of Ethics, available at https://journalofethics.ama-assn.org/article/medical-examination-immigrants-ellis-island/2008-04 (viewed February 25, 2025).

[10] Elizabeth Yew, M.D., “Medical Inspection of Immigrants at Ellis Island,” Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 1980, 56, 488-510, at 490, available at https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC1805119/pdf/bullnyacadmed00114-0060.pdf (viewed February 25, 2025).

[11] Elizabeth Yew, M.D., “Medical Inspection of Immigrants at Ellis Island,” Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 1980, 56, 488-510, at 491.

[12] Richard F. Gillum, “From Papyrus to the Electronic Tablet: A Brief History of the Clinical Medical Record with Lessons for the Digital Age,” The American Journal of Medicine, Vol. 126, No. 10, October 2013, at 854; Barbara L. Craig, “Hospital Records and Record-Keeping, c. 1850-1950 Part I: The Develop of Records in Hospitals,” Archivaria 29 (1989-90), 57-86, at 60-61.

[13] Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 78-80.

[14] Richard F. Gillum, “From Papyrus to the Electronic Tablet: A Brief History of the Clinical Medical Record with Lessons for the Digital Age,” The American Journal of Medicine, Vol. 126, No. 10, October 2013, at 854.

[15] Craig Robertson, “Granular Certainty, The Vertical Filing Cabinet, and the Transformation of Files,” Sciendo, April 2019.

[16] Craig Robertson, “Granular Certainty, The Vertical Filing Cabinet, and the Transformation of Files,” Sciendo, April 2019.

[17] Craig Robertson, The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information (University of Minnesota Press, 2021), 67.

[18] Craig Robertson, The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information (University of Minnesota Press, 2021), 68.

[19] Craig Robertson, The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information (University of Minnesota Press, 2021), 123.

[20] Craig Robertson, The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information (University of Minnesota Press, 2021), 75-91.

[21] Craig Robertson, The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information (University of Minnesota Press, 2021), at 97-98, 109.

[22] Craig Robertson, The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information (University of Minnesota Press, 2021), 140.

[23] An Act to revise, consolidate and amend the Statutes relating to Patents and Copyrights, July 8, 1870, 41st Congr, 2nd Sess., Section 90, 16 Stat. 198, available at https://www.wipo.int/wipolex/en/legislation/details/21576 (viewed February 27, 2025).

[24] Carla Hayden (foreword), The Card Catalog (Chronicle Books in association with the Library of Congress: 2017), at 103-07.

[25] Carla Hayden (foreword), The Card Catalog (Chronicle Books in association with the Library of Congress: 2017), at 108-13.

[26] Craig Robertson, The Filing Cabinet: A Vertical History of Information (University of Minnesota Press, 2021), 147-48.

[27] Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Harvard University Press, 2001), at 124.

[28] Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Harvard University Press, 2001), at 125. The pre-modern history of China’s use of fingerprints as signatures is discussed in ZHAO XIANGXIN 趙向欣 (1997) 中華指紋學 (Chinese fingerprinting). Beijing: Qunzhong chubanshe, as mentioned in Daniel Asen, “Knowing Individuals: Fingerprinting, Policing and the Limits of Professionalization in 1920s Beijing,” Modern China 2020, Vol. 46(2) 161 –192 (2019).

[29] Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Harvard University Press, 2001), at 128-34.

[30] Beverly Gage, G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Penguin Books: 2022), at 40-41.