The United States, HUMINT, and World War I Part 1

There’s so much material on human intelligence (HUMINT) collection leading up to and during World War I that I have to break it into two parts. In this first part, I lay out some of the modern aspects of HUMINT collection and organization. Then I explain how the French, British and Germans developed the practice prior to the U.S. entry into World War I, at which point the United States fell under a period of British and French tutelage. Next week in Part 2, we will need to discuss the American Protective League.

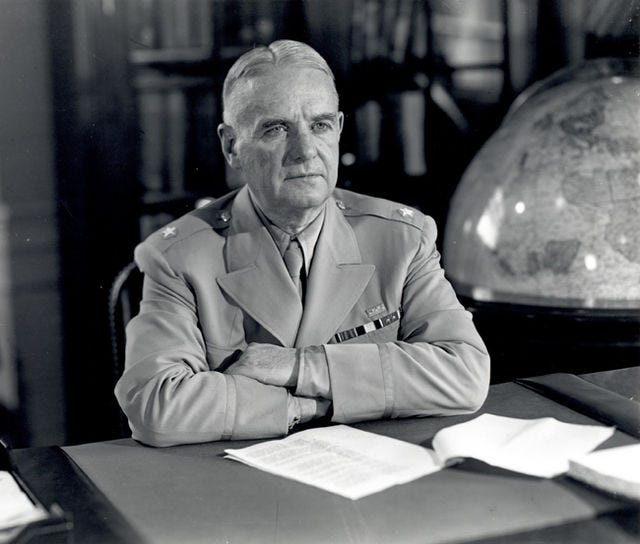

On March 26, 1916, a 33-year-old Irish-American lawyer and reserve cavalry officer from Buffalo, New York, purportedly on the payroll of the Rockefeller Foundation, disembarked from a ship at Southampton, England. He was first subjected to a 24-hour wait during which time British security services—most likely MI5—carefully screened all the passengers and arrested four, presumably on suspicion of being either German or Irish covert agents. From there, the American traveled to London and met briefly with a fellow U.S. citizen, Herbert Hoover, who was leading a U.S. relief effort to assist starving Belgians. He then proceeded to Rotterdam, where on April 13 he received both American and German permission to enter German-occupied Belgium. His trip took him from Brussels to Louvain, then Aachen, back to Rotterdam, then Stockholm, Berlin and Vienna, where he applied for but was denied a visa to enter Bulgaria—an odd itinerary for someone who had purportedly been sent by the Rockefeller Foundation to assist with Belgian relief efforts. He only returned in late June when notified that his cavalry unit back home had been called into service to support General Pershing’s punitive expedition into Mexico.[1]

While there is no definitive proof as to what exactly this American was doing, the paucity of information itself indicates that this might have been the first covert mission undertaken by William J. “Wild Bill” Donovan, future head of the World War II entity known as the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and predecessor to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). If so, he was most likely gathering information on behalf of British intelligence services, who would have wanted information on the German rear areas as the British military was planning an offensive on the Somme that would start in June 1916. In 1981, the CIA revealed that Donovan “probably” received British “military intelligence” training sometime during World War I.[2]

Human intelligence, or HUMINT, is the oldest of intelligence collection techniques. It is simply intelligence collected from human sources. According to the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence, while HUMINT is strongly associated in the public’s imagination with espionage and clandestine activities, “most of HUMINT collection is performed by overt collectors such as strategic debriefers and military attaches.”[3] In Donovan’s case—if he was indeed on a British military intelligence mission in 1916—it can take the form of simple reconnaissance, albeit sometimes under false pretenses. The term “clandestine,” in modern U.S. intelligence parlance, means “an activity or operation sponsored or conducted by governmental departments or agencies with the intent to assure secrecy or concealment.” A “covert” operation “hides the true intent, affiliation or relationship of its participants” and “[d]iffers from clandestine in that covert conceals the identity of the sponsor, whereas clandestine conceals the identity of the operation.” An intelligence operation can be both, which appears to be the case with respect to Donovan’s activities.[4]

Behind the seemingly simple act of collecting intelligence by talking to other humans, effective, large-scale and modern HUMINT collection requires a sophisticated infrastructure capable of organizing, coordinating and prioritizing collection efforts; targeting sources wisely; “deconflicting”[5] those sources; integrating counterintelligence (CI) efforts, and analyzing and processing useful intelligence from the results of HUMINT alongside other collection activities like SIGINT into what is known as “all-source intelligence.” Unclassified U.S. Intelligence Community Directives (ICDs) 304, 310 and 311 all hint at the extraordinary degree of careful coordination that occurs across all U.S. intelligence elements engaging in HUMINT.[6] The Director of the CIA is in charge of managing the national HUMINT collection capability and ensuring its integration into the National Intelligence Coordination Center.[7]

In addition to all this infrastructure, HUMINT collectors must receive standardized training on how to conduct human source contact, debriefings, liaison work and interrogations, in addition to understanding the very strict and elaborate parameters under which they are allowed to operate. The collection techniques are the same for both HUMINT collectors and CI agents, but HUMINT collection is governed by formal collection requirements, whereas CI collection is driven by threats. The U.S. Army’s Field Manual (FM) 2-22.3 Human Intelligence Collector Operations alone is 384 pages long.[8]

The French had started the process of professionalizing and bureaucratizing HUMINT well prior to the outbreak of World War I. In fact, the process had started much the same way and for the same reasons as they had for the United States: the French had colonies they needed to surveil and ultimately pacify; specifically, Algeria and later, Tunisia. The initial French military conquest of Algeria started in 1830 and ended in 1857; this was then followed, however, by a prolonged period of counterinsurgency warfare. The military responded by developing a political-civilian affairs institution called the bureaux arabes or Arab Offices, staffed by promising young military officers with a knowledge of Arabic or Berber, whose job in large part was to prevent insurgencies by maintaining an intelligence network that included both local notable elites and a bevy of informers.[9] .

As the French later expanded their influence into neighboring Tunisia, jostling against Italian interests, they leveraged the existing practices and expertise of the bureaux arabes, again exploiting the human intelligence provided to them by local ruling elites while at the same time co-opting those ruling elites into legitimizing French rule.[10] A promising young officer named Nicolas Jean Robert Conrad Aguste Sandherr was one of many who served in North Africa in this capacity after graduating from the Ecole de guerre in 1875.

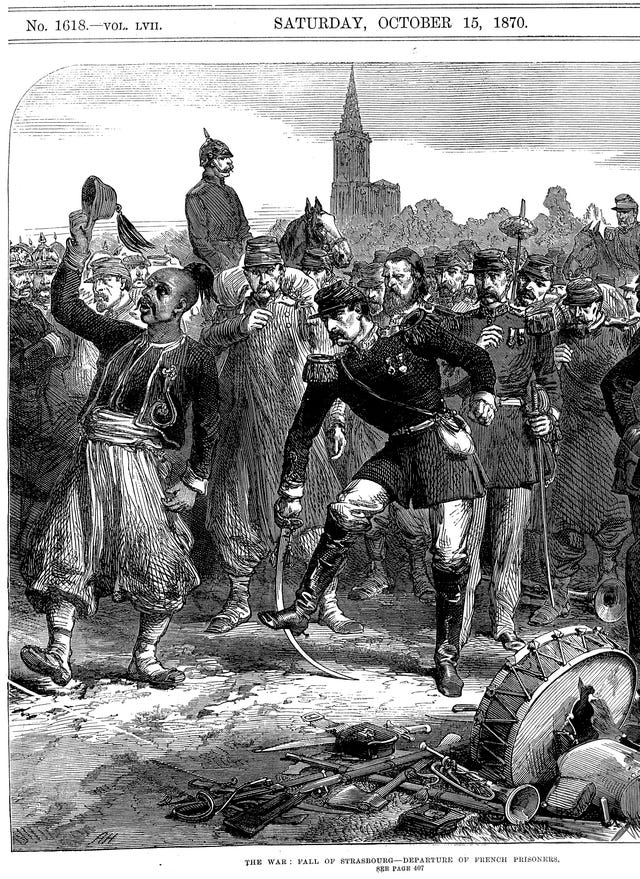

Following France’s humiliating defeat in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870, the Third Republic undertook an extensive revamping of its entire military to address the ongoing German threat to the French mainland. This effort relied heavily on officers who, like Sandherr, had colonial military intelligence experience. Two of the earliest thought leaders behind the comprehensive overhaul of the French Army and the treatment of intelligence as a specialized profession and modern “science” included General Ernest de Cissey, who had served in Algeria; and Colonel (later General) Jules Dewal, who had served in Africa (1852-59), Italy (1859-60), Mexico (1862-67), and Rome (1867-68).[11] In fact, “nearly every single officer who would take the lead in designing or directing French intelligence at the beginning of the Third Republic had served in Africa, where intelligence practices were commonplace.”[12] Under their leadership, the Deuxième Bureau (Second Office) was established directly under the État-Major Générale du Ministre de la Guerre (General Staff of the War Ministry), both modeled after their German equivalents; and within the Deuxième Bureau, a service de renseignements (SR), or intelligence service. The SR collected intelligence, while the Deuxième Bureau analyzed it.[13]

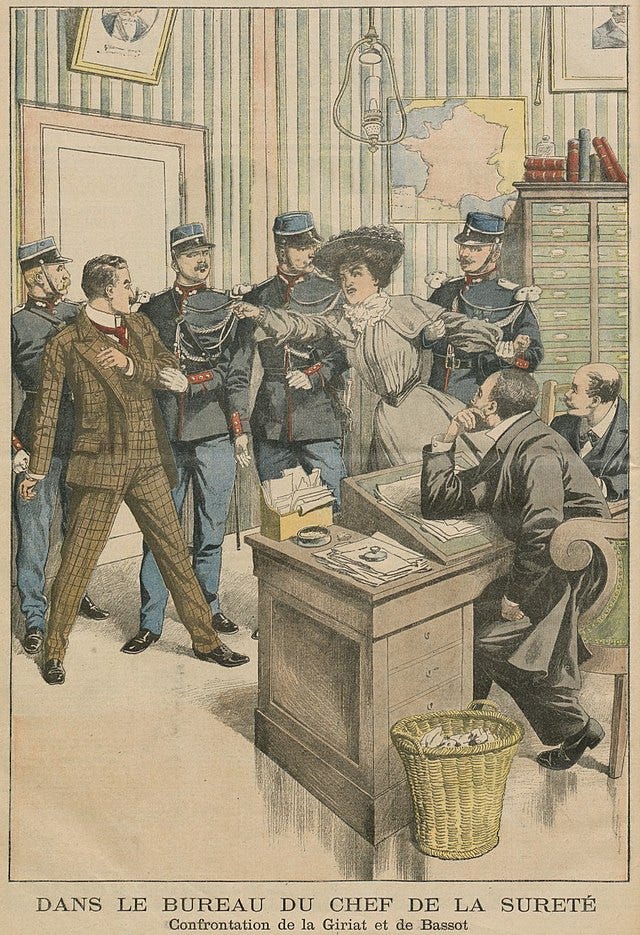

After Major Sandherr conducted a number of reconnaissance missions in Germany at the end of the 1870s that won him great praise, he joined the Deuxième Bureau’s SR in 1880. He was then sent back to Tunisia on an intelligence mission, but he returned to Paris in 1886 and served as the head of the SR’s Statistical Section until 1896, playing a key and rather infamous role in the notorious Dreyfus Affair.[14]

But the professionalization of HUMINT collection and analysis remained, the French continually motivated by the belief that their German counterparts were still far ahead of them in their ability to leverage espionage as ““a veritable science, with its rules, its precepts, its organization and its direction.”[15] In France, the SR was able to draw heavily upon the techniques developed by the French secret police over many centuries and leverage the resources of the Paris Police Prefecture’s investigative bureau or Sûreté; indeed, even today, “[t]he fight against the enemy within is one of the salient features of the French cultural [intelligence] model.”[16] In 1886, France passed a law criminalizing espionage (the United States would not have such a law until 1917), which gave the police and the military a basis for investigation.[17] By the 1890s, the French War Ministry had also developed a bureaucratic system for officially designating information as confidential, “very confidential,” secret, etc., and specifying the hierarchy of which individuals could have access to which type of information, an essential component for counterespionage against the Germans, and the proper handling of HUMINT along with other types of intelligence collection.[18]

Indeed, despite some of its missteps in the United States leading up to the U.S. entry into World War I, the German capacity for globally coordinating HUMINT collection, covert action and sabotage in 1917 was still formidable. Germany’s Section IIIb, which fell under its Army General Staff, maintained an efficient hub of military and naval intelligence for North and Central America in Mexico City, where German agents could gather daily in cafes and discuss operations. German intelligence successfully infiltrated the Mexican Army, with one of their many plants providing the Germans in October 1917 with a list of French expatriates who had campaigned for U.S. intervention in World War I. When M.N. Roy and several others associated with the “Hindu conspiracy” fled U.S. law enforcement authorities between 1916 and 1917, they were able to quickly re-establish their connections with German intelligence in Mexico.[19]

The British, as well, were able to effectively leverage global HUMINT collection into both MI5 (Security Service) and Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) operations (SIS would eventually be designated MI6, but not until World War II). MI5, officially designated as such on January 3, 1916, as part of a War Office reorganization, had three main branches: F (preventive intelligence), G (investigations), and H (secretariat, Registry and administration, including records management). While technically the “domestic” intelligence branch, MI5 had as much a global mission as the SIS as it dealt with threats to the entire British Empire; the head of F branch was additionally in charge of branches A (aliens), E (port and frontier control), and D (imperial and overseas, including Irish, intelligence). By the end of the war, MI5 had a total staff of 844. By the Armistice over 40 percent of staff were stationed outside London, while in London MI5 employed 291 female Registry and secretarial staff, an unusual number of women in the intelligence services for that time.[20] They tended to be upper-class women, whom male officials considered more trustworthy, with “old school ties” that helped them appreciate the value of keeping secrets for the common good.[21]

The SIS was more directly responsible for overseas HUMINT collection, including by covert agents. Headed by Mansfield Smith-Cumming, the SIS had started out in 1909 as an interagency creation, with the political backing of the Admiralty, but little support and some resentment from the War Office, which only “conceded responsibility for foreign work” amid some reluctance. Cumming was eventually given a list of existing agents along with the War Office’s “whole German Intelligence system,” but since the Foreign Office was not inclined to pay for them, Cumming was told to see what could get done with the agents “voluntarily.”[22]

Cumming, with no prior experience in espionage and no foreign language skills himself, nonetheless took to the work intuitively. In 1910 he arranged a bogus “cover address” in London with the Post Office for a fake import and export firm, “thus establishing a precedent for the classic ‘import and export’ espionage cover.”[23] For many years he relied on the voluntary help provided by British citizens, such as arms dealers, who could tell him what kinds of guns were being purchased by the German firm Krupp.[24] But by 1911, with appropriate funding, the SIS had agents in Copenhagen and throughout Belgium, sufficient to report, including to Home Secretary Winston Churchill, that two German divisions were concentrating in Malmédy, just across the Belgian border.[25] Cumming established a “frank and friendly” relationship with Colonel Charles-Édouard Dupont, the new head of the Deuxième Bureau, and by 1913 the head of the British War Office was directing specific HUMINT collection requests to the French through Cumming.[26]

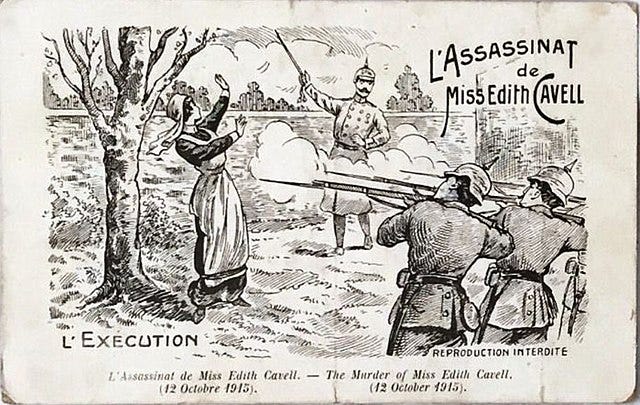

During the first half of 1914, Cumming’s SIS had two spy networks running in Belgium, whose job it was to watch German military centers and activities on Belgium’s eastern border.[27] Nonetheless, neither the SIS nor the French SR (who had an agent in Berlin and several in German-controlled Alsace-Lorraine) were able to successfully predict the German assault that was launched through Belgium and into France in August 1914.[28] With the outbreak of hostilities, SIS was able to address at least some of the intelligence needs of the British Expeditionary Force in northern France using agents from inside occupied Belgium. Many of these agents were women who helped voluntarily, sometimes paying with their lives. Among the first martyrs to the cause, not necessarily affiliated with the SIS, was a British nurse named Edith Cavell, who had been working in a hospital in Brussels when, in November 1915, she became part of an operation to smuggle wounded French and British soldiers out of Belgium using false papers. She was arrested by the German police, court-martialled and sentenced to death by firing squad, despite diplomatic protests by the United States, who tried to warn the Germans that her execution would harm Germany’s already damaged reputation. Indeed, the British issued a propaganda stamp afterwards, highlighting the barbarity of the nurse’s execution.

By the end of the war, the SIS fully accepted and even welcomed the contributions of female spies in Belgium, who wouldn’t hesitate to seduce German officers and who learned to draft their reports with secret ink.[29]

Under Cumming, the SIS also established networks farther afield than the Western front, while still concentrated mostly in Belgium and the Netherlands. By October 1916, the SIS had a total of 1024 staff and agents: this included 60 at headquarters, 300 in Alexandria, Egypt; 100 in Athens; 80 in Denmark; about 50 in Spain; and smaller numbers in Salonika, Romania, France, Switzerland, Russia, Norway, Sweden, Malta, Italy, South Africa, South America, and of course, New York, where he had posted Sir William Wiseman.[30] Cumming had a number of agents on hand in Petrograd in 2017 to witness the February revolution and abdication of Tsar Nicholas II. Over the next several months, these agents tried their best to keep Russia in the war effort by propping up Prime Minister Alexander Kerensky against the growing power of the Bolsheviks organizing under Lenin. To that end, in July 2017, Cumming and Wiseman recruited the writer Somerset Maugham, then vacationing in Long Island, to travel to Moscow and deliver $150,000 to Kerensky in person, providing half the amount through British funds and convincing the U.S. Government to supply the other half as a joint effort.[31]

By the end of April 1917, by which time Major Ralph Van Deman had overcome the initial bureaucratic hurdles to establishing a Military Intelligence Section (as discussed in last week’s post),

both the British and the French military missions to the United States were on hand to help him design the new organization, each jostling for overall control of the American alliance. The French delegation had left for Washington the moment the United States entered the war, headed by Marshal Joseph Joffre, who had been chief of the army’s General Staff from 1911 to 1916. They were offering training to the infantry and artillery units of the new National Guard and National Army divisions, since the U.S. regular army units were already on their way to France, bringing with them most of the qualified American instructors. A total of 330 French officers would eventually provide instruction and advice as part of their military mission to the United States, including for the U.S. General Staff.[32]

The British and French intelligence officers associated with each mission provided valuable guidance to Van Deman on how to organize his section. In the end, Van Deman decided to model his section more along the lines of the British model, as it was his perception that in France, counter-espionage was handed by the Sûreté, a civilian agency, whereas he wanted the entire intelligence enterprise to be completely under the auspices of the War Department.[33] He may have misunderstood the SIS to have been subordinate to the War Office, as the two were engaged in an interagency turf battle at the time, with Major General George MacDonough as the head of the War Office’s Military Intelligence Division insisting that Cumming reported to him.

The counterespionage mission was of the utmost importance to Van Deman and a variety of other senior officials, given the recent history of German spying and sabotage. From Attorney General Gregory’s perspective, the Justice Department was in charge of all counterespionage investigations, and it was long past time to assert the Bureau of Investigation (BI)’s supremacy over the Secret Service agents competing against the BI under the auspices of the Treasury Department.[34] (I discussed this dynamic in this post):

On June 15, 1917, the U.S. Congress finally enacted the Espionage Act that the U.S. Justice Department had been pushing since 1915. To his SIS superiors in London, William Wiseman claimed authorship of the law itself, a somewhat exaggerated claim on his part, although the Act did draw from Britain’s Official Secrets Act and the 1914 Defense of the Realm Act for inspiration.[35]But the passage of the law was not accompanied by any additional staffing or funding for federal personnel, whether civilian or military, who would be needed to enforce this law.

(to be continued)

[1] Anthony Cave Brown, The Last Hero: Wild Bill Donovan : the biography and political experience of Major General William J. Donovan, founder of the OSS and "father" of the CIA, from his personal and secret papers and the diaries of Ruth Donovan (New York: Vintage Books, 1984), at pp. 30-35.

[2] Anthony Cave Brown, The Last Hero: Wild Bill Donovan : the biography and political experience of Major General William J. Donovan, founder of the OSS and "father" of the CIA, from his personal and secret papers and the diaries of Ruth Donovan (New York: Vintage Books, 1984), at 33.

[3] ODNI, “What is Intelligence?” available at https://www.dni.gov/index.php/what-we-do/what-is-intelligence (viewed January 11, 2025).

[4] COL Mark L. Regan, Ed., Office of Counterintelligence (DXC), Defense CI and HUMINT Center, Defense Intelligence Agency, Terms and Definitions of Interest for DoD Counterintelligence Professionals, May 2, 2011, available at https://www.dni.gov/files/NCSC/documents/ci/CI_Glossary.pdf (viewed January 11, 2025).

[5] “Deconfliction” is “The process of sharing information regarding collection between multiple agencies to eliminate potential duplication of effort, multiple unintended use of the same source, or circular reporting.” COL Mark L. Regan, Ed., Office of Counterintelligence (DXC), Defense CI and HUMINT Center, Defense Intelligence Agency, Terms and Definitions of Interest for DoD Counterintelligence Professionals, May 2, 2011, available at https://www.dni.gov/files/NCSC/documents/ci/CI_Glossary.pdf (viewed January 11, 2025).

[6] These and all other ICDs are available on the ODNI website at https://www.dni.gov/index.php/what-we-do/ic-related-menus/ic-related-links/intelligence-community-directives (viewed January 11, 2025).

[7] ICD 304 Human Intelligence, Effective March 6, 2008, amended July 9, 2009, available at https://www.odni.gov/files/documents/ICD/ICD-304.pdf (viewed January 11, 2025).

[8] Headquarters, Department of the Army, FM 2-22.3 Human Intelligence Collector Operations, September 2006, available at https://irp.fas.org/doddir/army/fm2-22-3.pdf (viewed January 11, 2025).

[9] Jacque Frémeaux and Bruno C. Reis, “French Counterinsurgency in the Era of the Algerian Wars, 1830-1962,” in Beatrice Heuser and Eitan Shamir, eds., Insurgencies and Counterinsurgencies: National Styles and Strategic Cultures (Cambridge University Press, 2017), 44-74, at 52.

[10] Omar Safi, The Intelligence State in Tunisia: Security and mukhabarat, 1881-1965 (I. B. Tauris & Company, Ltd, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020), at 31.

[11] Deborah Susan Bauer, Marianne is Watching: Knowledge, Secrecy, Intelligence and the Origins of the French Surveillance State (1870-1914), Ph.D. thesis, UCLA (2013), at 124-27, available at https://escholarship.org/content/qt7rt4z6js/qt7rt4z6js.pdf (viewed January 12, 2025).

[12] Bauer at 179.

[13] Richard Deacon, The French Secret Service (Grafton Books: London, 1990), at 79.

[14] Bauer at 200-02.

[15] Bauer at 111.

[16] Bauer at 33.

[17] This law is reproduced (in both French and an English translation) in Bauer at Annex D.

[18] Bauer at 146-47.

[19] Jamie Bisher, the Intelligence War in Latin America, 1914-1922 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2016), at 136-38.

[20] Christopher Andrew, Defend the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (Alfred A. Knopf, 2009), at 85; Tammy M. Proctor, Female Intelligence: Women and Espionage in the First World War (New York University Press: London, 2003), at 57-59.

[21] Tammy M. Proctor, Female Intelligence, at 67.

[22] Keith Jeffery, MI6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909-1949 (Bloomsbury Publishing: London, 2010), at 11-17.

[23] Jeffery at 17.

[24] Jeffery at 20.

[25] Jeffery at 26-27.

[26] Jeffery at 31.

[27] Jeffery at 33.

[28] Jeffery at 34; Richard Deacon, The French Secret Service (Grafton Books: London, 1990), at 83-88.

[29] Jeffery at 66.

[30] Jeffery at 68.

[31] Giles Milton, Russian Roulette (Bloomsbury Press: New York, 2013), at 54.

[32] Jennifer D. Keene, “Uneasy Alliances,” French Military Intelligence and the American Army During the First World War,” Intelligence and National Security, Vol. 13, 1998, pp. 18-36, at 19.

[33] Ralph E. Weber, ed., The Final Memoranda: Major General Ralph H. Van Deman, USA ret.,1865-1952: Father of U.S. Military Intelligence (Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1988), at 23 (firsthand account of Van Deman).

[34] Joan M. Jensen, The Price of Vigilance (Rand McNally: Chicago, 1969), at 16.

[35] See Jennifer Luff, “The Anxiety of Influence: Foreign Intervention, U.S. Politics, and World War I,” Diplomatic History 44(5): 756-785 (November 2020), at 775-77, citing to, inter alia, Revision and Strengthening of Espionage, Neutrality, Passport and Shipping Regulations, April 10, 1917, 64th Cong. 2nd Sess. (Washington, DC, 1917), at 15.