California and the Immigration Act of 1924

If you think I've forgotten the Great Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920, wait till the end

In 2015 in an interview with Breitbart, Republican Senator and future Attorney General Jeff Sessions waxed eloquent about the 1924 Immigration Act, also known as the Johnson-Reed Act, stating that the flow of immigration had been dangerously high and that the law had been necessary to slow down immigration significantly, adding “And we then assimilated through to 1965 and created really the solid middle class of America with assimilated immigrants. And it was good for America.” He added that President Calvin Coolidge, in signing the law, declared “I’m doing it for recent immigrants, because they’re getting hammered in their wages in [the United States’] acceptance of too large a flow.”[1]

Sessions was most likely referencing the national-origin-based quota system that regulated the flow of Eastern and Southern Europeans. However, the passage of the 1924 Act, which included an absolute bar (not a quota) on all Asian immigration, initially prompted an act of hara-kiri in front of the former U.S. Embassy in Tokyo, with a letter on the deceased man’s body urging his nation “to rise up to avenge the insult embodied in the action of America.” The Tokyo Asahi reported that the police on the scene regarded the ritual suicide as “tragic but magnificent.”[2] Within a decade, Japan had invaded Manchuria, to international condemnation, and formally withdrawn from both the League of Nations and the 1922 Washington Naval Disarmament Treaty, setting it on a path of militarization and inevitable conflict with the United States, culminating in the December 7, 1941 surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

How we got from a law primarily seeking restrictions on European immigration to an existential conflict with Japan I will be covering in the next several posts.

The major players in the drama that unfolded during the debate over the 1924 Immigration Act included primarily the following:

(1) The California contingent: Its US Congressional delegation and their grassroots supporters back home

(2) The internationalists: Japanese Ambassador to the United States Hanihara Masanao and Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes

(3) The restrictionists (who, unlike the Californians, were focused on Southern and Eastern European immigrations; i.e., Italians and Jews)

(4) The East Coast cosmopolitans (led more or less by Fiorello La Guardia, whom I discussed last week); and finally

(5) The militarists; i.e., those in both the Japanese and U.S. armed forces, particularly the two navies, who, whether they knew it or not, shared an interest in getting out from under the restrictions on shipbuilding that resulted from the Washington Naval Disarmament Conference.

Today I’m going to cover the California contingent, for no particular reason, because I am definitely not writing a current events blog.

The California Congressional Delegation and Their Supporters

For the contingent that purported to represent California’s interests in the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924, the possibility of total exclusion of Japanese immigrants in the 1924 Act, along with all other "Asiatics,” represented the culmination of over two decades’ worth of effort. In the Congressional debates, the effort to insert an exclusion provision was led on the Senate side by Republican Senator Samuel M. Shortridge and on the House side by Democratic Congressman John E. Raker, with occasional help from Republican Congressman Walter Lineberger. The grassroots support for this wonderfully bipartisan effort came from a coalition organization called the Japanese Exclusion League of California, which represented the American Legion, War Veterans, Native Sons and Native Daughters of the Golden West, State Federation of Women’s Clubs, and the State Federation of Labor. Other various civic organizations involved included the Grange, the Los Angeles County Anti-Asiatic Association, and the Japanese Exclusion League of Washington. The American Federation of Labor (AFL) under Samuel Gompers was also strongly in favor of Japanese exclusion. [3]

In 1908, the Japanese diplomat Hanihara had prepared a report for the Japanese Foreign Ministry greatly concerned about the poor impression being left by a class of unskilled, itinerant Japanese laborers in the United States that the U.S.-based Japanese farmers referred to derisively as the “blanket-carriers.”[4] (I talked about his report in this post):

In reality, it was the successful Japanese farmers of California who were fomenting all this grassroots opposition against them. But how had all these Japanese immigrants wound up in California in the first place?

Here We Go Back to 1898 again

The answer lies in the aftermath of my favorite understudied U.S. conflict, the Spanish-American War of 1898, and the acquisition of Hawai’i that took place that same year, instantaneously transforming the United States into a Pacific island empire. If you’re joining my Substack late and/or just haven’t had enough of my obsession with these two seminal moments in U.S. history, read this post:

and probably also this one:

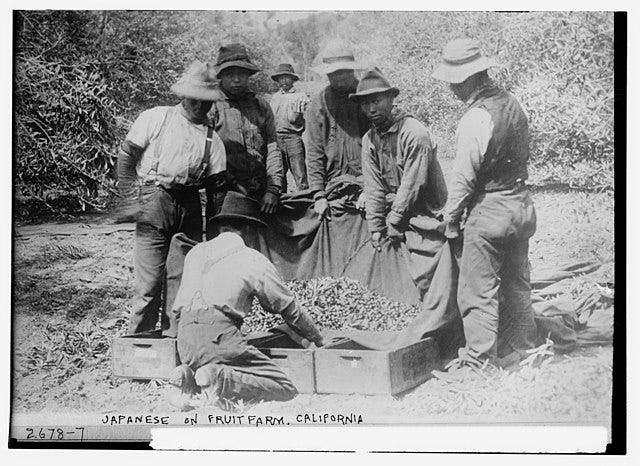

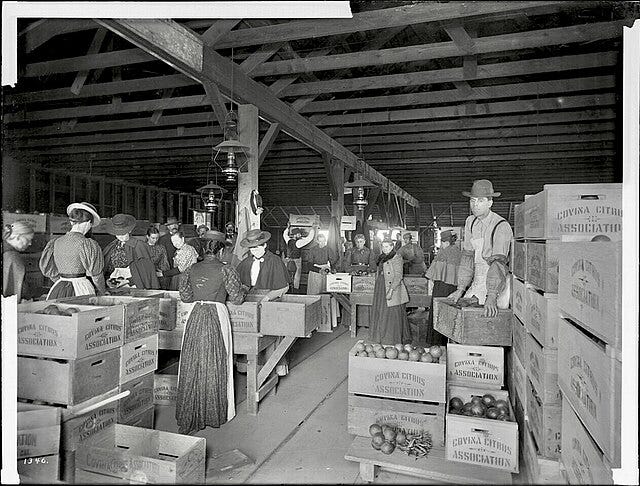

One of the most immediate impacts of the U.S. annexation of Hawai’i was that Hawai’i was now subject to U.S. immigration law, which since 1885 had forbidden contract or “coolie” labor. Thus, all indentured labor contracts were immediately abrogated, reportedly liberating “thousands of Asiatic peons.” Apparently quite a few of them, who were of Japanese descent, decided to make their way to the U.S. mainland, settling in California. California was at that time experiencing a significant shift in its agriculture, from wheat to smaller-farm production of cotton, sugar beets, fruits and vegetables, which required more intensive use of farm labor.

Thus, while some Japanese came from Hawai’i to fill this unskilled agricultural labor need, the majority of them were recruited and came from Japan proper.[5] Steamship lines and emigration companies were more than happy to profit off of this mass migration. In the year 1900 alone, 12,628 Japanese entered the United States. It didn’t take long for the city of San Francisco, and then the California state legislature, to adopt resolutions extending California’s hard-won federal Chinese exclusion policy to Japanese immigrants as well, in May 1900 and January 1901, respectively.[6]

The Empire of the Rising Sun

The problem was, the U.S. federal government was at that time trying very carefully to manage its bilateral relationship with Japan, a relationship that had been placed on tenterhooks precisely because of U.S. empire-building in the Pacific. In 1897 Japan had lodged a formal protest against the newly signed treaty of annexation between Hawai’i and the United States. Only after several weeks of tension and formal assurances from the United States that Japanese immigration rights into Hawai’i would continue to be respected did the Japanese government formally withdraw its protest.[7]

As for the Philippines, if Japan had ever articulated its own version of the U.S. Monroe Doctrine--a doctrine providing for automatic objections to any attempt by European powers to colonize or subjugate any of the United States’ immediate neighbors—it most definitely would have included the Philippines. By 1900, Japan was in a vastly different position than China. Japan had managed to not only resist colonization but begin to be recognized by Western powers as a great power in its own right. It had even, through the rigorous legal and institutional reforms of the Meiji Restoration, thrown off the humiliating assertion of Western extraterritorial jurisdiction over Western nationals in Japan’s territory via the “unequal treaties.”[8]

(which I talked about here):

When Japan achieved a stunning military and naval victory over Russia in 1905, both the British and U.S. Governments (under President Theodore Roosevelt) knew, lest they doubted, that Japan was an emerging Pacific power not to be trifled with.

It was also a power that had industrialized so quickly that it was now heavily dependent upon access to raw materials and agricultural products from the Asian mainland as well as the larger Asian archipelagos. [9] One way to ensure continued access to these regions was through Japanese emigration. Japan gradually conquered and then annexed Korea in 1910, to which American Christian missionaries were on hand to bear witness. The missionaries came away from the experience not entirely enamored of the Japanese.

To white Californians, Japan’s defeat of Russia—the first ever military defeat of a white “Western” power by an Asian one—set off a wave of paranoia that California was next on the list of Japan’s anticipated conquests. In October 1906, the San Francisco Board of Education ordered the segregation of Japanese students in the public schools (a whopping total of 93 Japanese pupils out of a school population of 29,000). The Japanese government immediately protested, and President Roosevelt denounced the measure as a “wicked absurdity” in his December 1906 address to Congress. The following year, Secretary of State Elihu Root negotiated the so-called “gentleman’s agreement” between the U.S. and Japan, Hanihara assisting the then-Japanese Ambassador to the United States Aoki Shūzo, an informal, unpublished non-treaty, pursuant to which Japan agreed to limit the issuance of passports to its emigrants to either non-laborers or to such laborers as had already established a domicile in the United States.[10] Already, 66,000 Japanese had come to the continental United States directly from Japan, with another 35,000 total having come by way of Hawai’i.[11]

Japanese Tenant Farmers Establish Foothold

Unskilled agricultural labor, as we have seen in the instance of the sugar plantations of Hawai’i, is generally low-paid, backbreaking work. An agricultural laborer who has the opportunity to do absolutely anything else for a living will generally do that. The Chinese immigrants who had come to California during the gold rush had gradually transitioned into urban-based entrepreneurship (restaurants, laundries, etc.). The Japanese immigrants in California, by contrast, had been tenant farmers in Japan, coming mostly from southwestern Japan, where they worked small plots of land,[12] and they preferred to be tenant farmers in California as well. Under tenancy they could more effectively utilize family labor to increase their income and save money to purchase land. By 1910, 233 farms were owned or co-owned by Japanese immigrants and/or Japanese-Americans, with an additional 36 managed by Japanese, while 1,547 farms were worked by Japanese tenant farmers.[13] The U.S. Supreme Court would later find that, between 1900 and 1910, the total acreage of “Japanese-controlled” farms in California had increased from 4,698 to 99,254 acres.[14]

White Californians responded with the 1913 Alien Land Law, prohibiting foreign nationals ineligible for citizenship from owning agricultural land. Since a 1911 treaty between the United States and Japan protected the right of Japanese nationals to lease land for residential and business property, California could only prohibit the sale of agricultural land, but as the law was quite obviously intended to target Japanese farmers, this was entirely the point. The Supreme Court of California stated openly that the precise purpose of the law was “to discharge the coming of Japanese into this state.” One of the authors of the law, California Attorney General Ulysses S. Webb, said explicitly that the Japanese were an “undesirable race” and that the law purposefully sought “to limit the numbers who will come by limiting the opportunities for their activity here when they arrive.”[15] Webb believed that what made the Japanese “undesirable” was actually their hard work and efficiency; he opined that “[i]f the Oriental farmer is the more efficient, from the standpoint of soil production, there is just that much greater certainty of an economic conflict which it is the duty of statesmen to avoid.”[16]

The 1913 Alien Land Law was widely perceived as being virtually impossible to enforce. The white Californians who continued to advocate for Japanese exclusion believed, or at least promoted the belief, that the Japanese en masse had conspired to exploit a “loophole” in the law by purchasing land in the names of their minor, American-born children. The children were, of course, automatically U.S. citizens thanks to the constitutional birthright citizenship rights that a Chinese immigrant had secured for them in United States v. Wong Kim Ark in 1898.[17] The parent of the U.S. citizen would then have himself appointed as guardian and effectively work the land on behalf of the child owner.

This did happen, although there were other reasons why Japanese immigration and influence over the agricultural sector continued to expand between the years 1913 and 1920. One of them was World War I, in which Japan fought on the side of the Allies against Germany, during which period the 1908 “gentleman’s agreement” was loosely enforced and, at any rate, was not applicable to the wives and children of immigrants. Another factor was simply that the entire country was desperate for foreign unskilled labor, during a time period in which European immigration had slowed to a trickle and many working-age American men were enlisted in the armed forces.

(I talked about the first Bracero Program, a U.S.-Government sponsored effort during World War I to import Mexican agricultural laborers, in this post):

Thus, for a variety of reasons, by 1919, the California state board of control was reporting that “the Japanese” in California (presumably including both Japanese immigrants and U.S.-born Japanese-Americans) either owned or had contracted to buy 74,769 acres of agricultural land and leased or held by contract 383,287 acres.[18]

This was still but a tiny fraction of California agricultural acreage; nonetheless, the revelation set off a whole new round of anti-Japanese agitation, and the 1920 ballot for Californians included Proposition 1, a revision to the Alien Land Law that would now prohibit all rental of land, as well as aliens holding stock in corporations owning or leasing farmland. Meanwhile, U.S. Senator James Phelan was running for re-election on the campaign slogan “Keep California White.” Phelan lost his re-election bid, but Proposition 1 passed by a three-to-one margin. In 1923, California further amended the law to bar aliens ineligible for citizenship from acting as guardians of minor citizen children owning land.[19]

Californians take note of Hawai’i

What does all this have to do with the Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920, you might ask? For starters, if you recall, James Phelan, a former San Francisco mayor, was among the U.S. Senators who received the Hawai’ian sugar plantation owners’ emissaries in February 1920, with great interest in what the Japanese strikers had been doing to undermine the U.S. sugar industry, as well as whether Japanese laborers were the cause of a construction mishap at the new naval base at Pearl Harbor.

In March 1921, the Los Angeles Examiner featured breathless coverage of the sugar strike in its ongoing series on Hawai’i that had led off with the headline "Jap Menace Lies Black on Pacific!"

And in the spring of 1923, as plans in the U.S. Congress were afoot to render the 1921 emergency quota system a permanent feature of U.S. immigration law, Congressman Raker of California travelled to Hawai’i and spent two and a half months there, visiting every island and every sugar plantation except one.

Whether Raker and the rest of the California contingent ever heard, understood or acknowledged the complete story of the Oahu sugar strike—including the part where machete-wielding Filipinos started it and then intimidated Japanese workers into going along with it—they had arrived at a certain narrative about the strike that suited their own political purposes, and they were going with it. On April 8, 1924, as part of the debate over the 1924 Immigration Act, Raker regaled his colleagues on the House floor with the insights he had gained from his Hawai’ian travels, using a chart that he said showed “the story of a century”:

Look at this chart. Here is a graphic presentation of the past, present, and future of Hawaiians disappearing. Japanese already risen to predominance, and whites in hopeless minority.

You will see here demonstrated that in 1900 there were 230,000 Hawaiians. Look at the line coming down and you will see that there are now 23,723 Hawaiians on the Hawaiian Islands.

Now look again: Hawaiians, 18,000. For a while there were many others, but they pinched them out.

With the gentleman’s agreement that there was to be no increase in the Japanese population in the islands or the possessions of the United States or in continental United States, starting in 1880 down to 1890 they got very few, and they run up until there was 109,274 Japanese in the Hawaiian Islands. I visited the schools of the Hawaiian Islands, one where the teacher told me there were over a thousand pupils present. So help me God, there were not over six white people attending that school. Anybody knows that within the last 10 years with those born in Hawaii they can dominate everything in the island of Hawaii and elect all the officers. Then they say there is no danger in this increase of population.[20]

The story of the Japanese in Hawai’i, and their nefarious attempt to collapse and then take over the sugar industry by fomenting a strike, was to now serve as one more arrow in the Californians’ quiver, as they aimed at a wholesale exclusion of all “Asiatic” immigration in the 1924 Immigration Act, “gentleman’s agreement” be damned.

Still don’t understand how the Oahu sugar strike connects to everything else? That’s okay. Next week we’ll take on the internationalists, starting with Ambassador Hanihara and the waning era of cherry blossom diplomacy.

[1] Interview of Senator Jeff Sessions by Stephen K. Bannon, Breitbart, October 5, 2015, available at https://www.breitbart.com/politics/2015/10/05/exclusive-jeff-sessions-obamatrade-can-killed/ and

(viewed May 26, 2025) (remarks made about the 1924 Act just before the 3-minute mark).

[2] Izumi Hirobe, Japanese Pride, American Prejudice: Modifying the Exclusion Clause of the 1924 Immigration Act (Stanford University Press, 2001), at 33.

[3] Congr. Rec.-Senate, April 8, 1924, at 5808 (quoting Senate Joint Resolution No. 26 Introduced in California legislature by Senator Sharkey, April 4, 1921. Passed by California Senate April 12, 30 to 0; passed by aseembly April 13, 55 to 9).

[4] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 73.

[5] Masao Suzuki, Important or Impotent? Taking Another Look at the 1920 California Alien Land Law, Journal of Economic History, Vol. 64 No. 1 (Mar. 2004) pp. 125-143, at 126.

[6] Edwin E. Ferguson, The California Alien Land Law and the Fourteenth Amendment, 35 Calif. L. Rev. 61, at 63-64 (March 1947).

[7] Gerald E. Wheeler, Prelude to Pearl Harbor: The United States Navy and the Far East, 1921-1931 (University of Missouri Press, 1963), at 48.

[8] Turan Kayaoglu, Legal Imperialism: Sovereignty and Extraterritoriality in Japan, the Ottoman Empire, and China (Cambridge University Press, 2010), 66-68.

[9] Gerald E. Wheeler, Prelude to Pearl Harbor: The United States Navy and the Far East, 1921-1931 (University of Missouri Press, 1963), at 31.

[10] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 69-70.

[11] Masao Suzuki, Important or Impotent? Taking Another Look at the 1920 California Alien Land Law, Journal of Economic History, Vol. 64 No. 1 (Mar. 2004) pp. 125-143, at 127.

[12] Alan Takeo Moriyama, Imingaisha: Japanese Emigration Companies 1894-1908 (University of Hawaii Press, 1985), at 13.

[13] Masao Suzuki, Important or Impotent? Taking Another Look at the 1920 California Alien Land Law, Journal of Economic History, Vol. 64 No. 1 (Mar. 2004) pp. 125-143, at 128.

[14] Oyama v. California, 332 U.S. 633 (1948), at 654-55.

[15] Id., at 657, quoting Estate of Testsubumi Yano, 188 Cal. 645, 658, 206 P. 995, 1001, and Ulysses Webb’s speech before the Commonwelath Club of San Francisco on August 9, 1913.

[16] Id. at Footnote 3/10.

[17] 169 U.S. 649 (1898).

[18] Edwin E. Ferguson, The California Alien Land Law and the Fourteenth Amendment, 35 Calif. L. Rev. 61, at 68 (March 1947).

[19] Masao Suzuki, Important or Impotent? Taking Another Look at the 1920 California Alien Land Law, Journal of Economic History, Vol. 64 No. 1 (Mar. 2004) pp. 125-143, at 130.

[20] Congr. Rec. 5890-5891 (April 8, 1924)(remarks of Congressman Riker).