As I mentioned two weeks ago before taking a slight detour to talk about Afrikaners:

I currently owe an explanation to my wife as to how my strange obsession with the Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 ties into the rest of my scholarship, which is about the interplay between colonialism and surveillance. As I began to explain here:

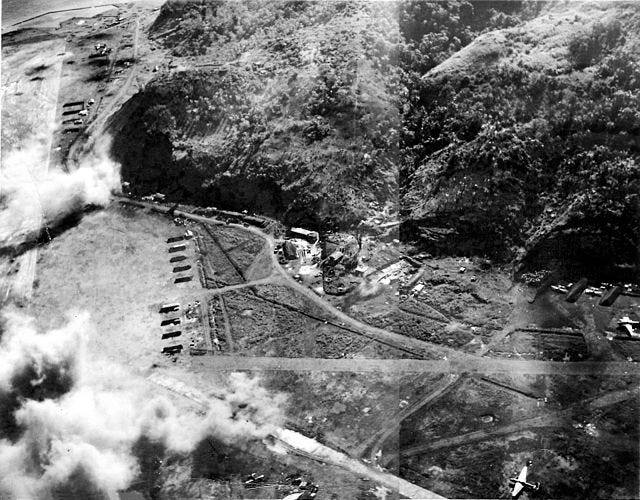

the origins of the modern U.S. surveillance state, particularly with regard to NSA and Signals Intelligence (SIGINT) capacity, are to a large degree traced back to the December 7, 1941 Japanese “surprise” attack on Pearl Harbor. So what I’m trying to show is that, with or without a SIGINT capacity, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor really should not have come as any great surprise (the method of attack was a legitimate surprise, which I’ll get into as we get closer to 1941). Arguably, the fate of the U.S.-Japan relationship was sealed with the United States’ decision to annex the Philippines following the Spanish-American War of 1898. Nonetheless, there were still many off-ramps to this epic showdown between the two Pacific naval powers that the United States could have chosen to take and did not.

What we’re going to get into today is how the U.S.-Japan relationship deteriorated to such an extent that such an attack was all but inevitable. I will continue to put in bold any references to Pearl Harbor so we don’t lose track.

Flashback to 1908: When Japan sends its people, they’re not sending their best

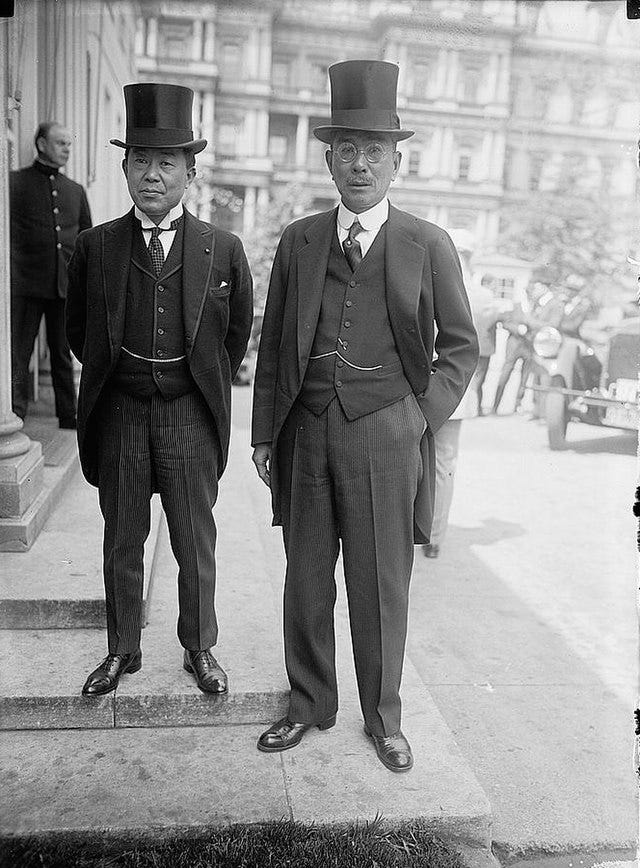

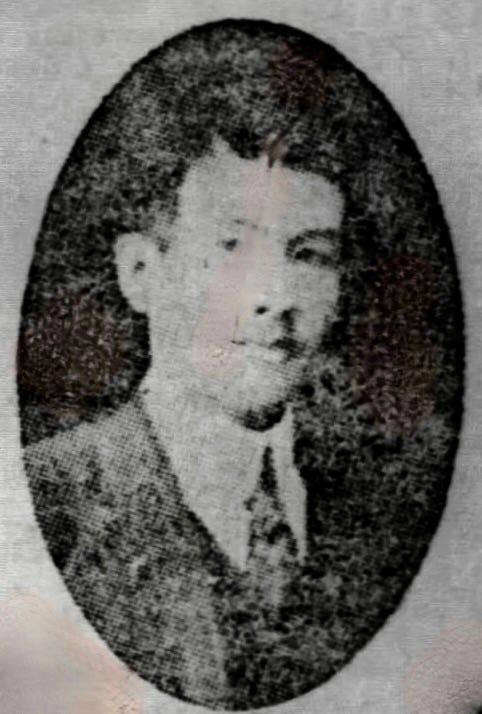

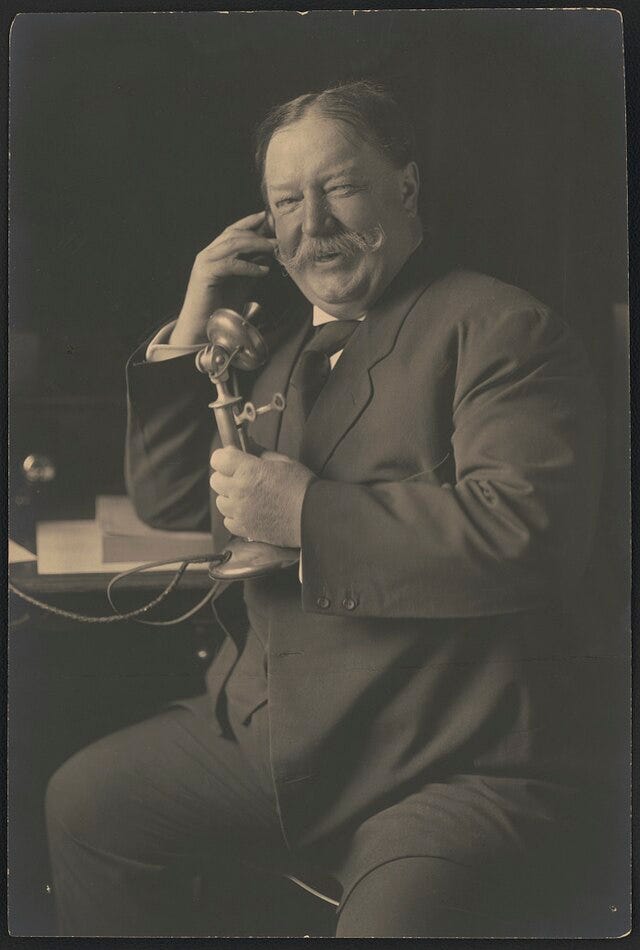

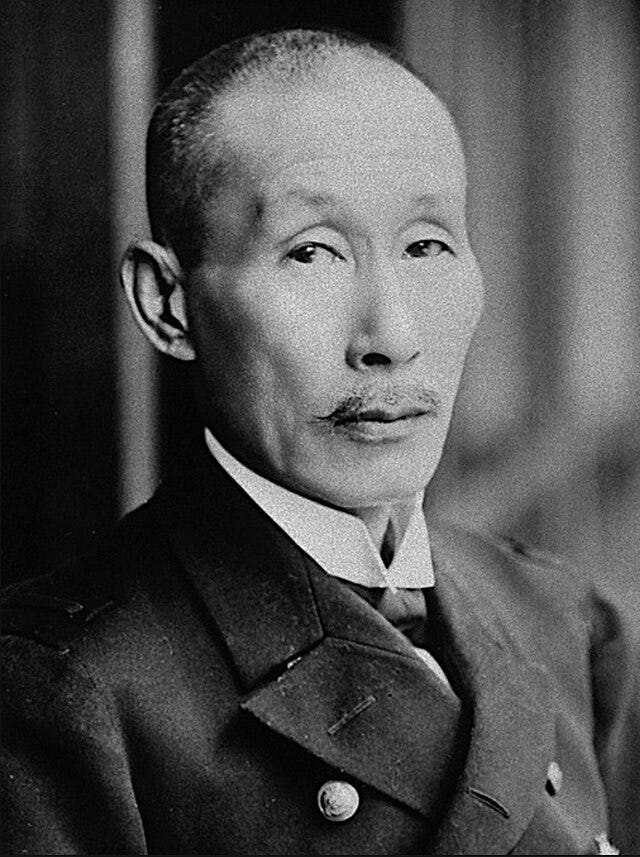

In 1908, the year before the first Japanese strike on the sugar plantations of Hawai’i and the U.S. Navy broke ground on Pearl Harbor, a 33-year-old up-and-coming Japanese diplomat named Hanihara Masanao undertook a multi-state fact-finding tour of the United States to examine the living standards of the Japanese immigrant or nisei community. The diminutive Hanihara, absolutely fluent in English, had by then already become a beloved figure in Washington circles, where President Roosevelt, President Taft and anyone else he interacted with at the State Department knew him simply as “Hany.” Once, at a public dinner in New York, the notoriously rotund President Taft lost his escort, spotted Hanihara, grabbed his arm and said, “Come along, Hany. We are about the same size.” “The grand entrance of the two side by side, ‘one physically typify[ing] America and the other Japan,’ was met with great applause. The episode eloquently speaks to the sense of humor the two men shared.”[1]

For his fact-finding tour, Hanihara over the course of several months managed to travel to New Orleans, along the Texas border with Mexico, and throughout numerous Western states. He didn’t make it to Hawai’i, but what he saw in California and Colorado in particular was appalling. The majority of nisei at that time were simply unskilled, itinerant laborers who moved from place to place seeking work, and who lived in sub-human conditions, often sleeping in groups of 20 to 30 in field sheds on straw spread over dirt floors. The few Japanese farmers who lived in settled communities in the United States referred to this class of laborers as “blanket carriers.” As Hanihara reported, “With only a piece of blanket on their backs, they move from one place to another looking for work. In this situation, their behavior tends to be unruly and often unnecessarily creates hostility and antagonism among the local community.”[2]

Hanihara was particularly concerned about the “Japan towns” that arose to serve this class of laborers. These areas were often on the fringe areas of cities like Denver and, if they appeared to be normal shops during the days catering to Japanese language customers, by night they converted to brothels, bars, gambling dens and other seedy establishments, some run by Chinese criminal elements. Hanihara was shocked at the vulgar behavior of his countrymen and lamented in his report (which was sealed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs for decades afterwards) that, because most Americans of that era had never visited Japan, they assumed that all Japanese simply lived this way. This class of laborer, which became known throughout the Americas as Dekasegi (出稼ぎ), literally “working away from home,” indeed became the basis for U.S. policymakers’ assertions that the Japanese were simply incapable of assimilating into the American way of life.

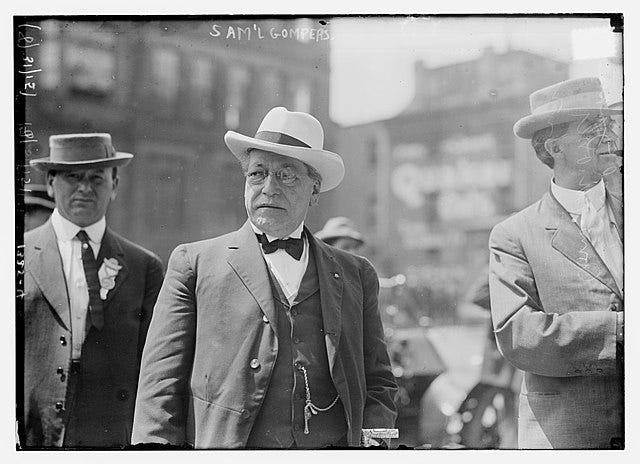

One such policymaker was U.S. Senator James D. Phelan of California, who had pushed for passage of the U.S. Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, served as mayor of San Francisco during an outbreak of bubonic plague within the city’s Chinese community between 1900 and 1904, and was elected to the U.S. Senate in 1915 on a platform of Japanese exclusion. In that regard, Phelan was strongly supported by the 5-million-member American Federation of Labor (AFL) under the leadership of Samuel Gompers, who had declared in 1905 that "[t]he Caucasians are not going to let their standard of living be destroyed by Negroes, Chinamen, Japs or any others."[3]

By the time Phelan was elected to the Senate, the Asiatic Exclusion League was in full bloom in both the U.S. Pacific Northwest and British Columbia, collaborating to exclude Japanese and Korean immigrants, continue rigorous enforcement of the Chinese Exclusion Act, and deal with the more recent influx of Hindu and Sikh immigrants into the lumber yards, as I previously discussed here:

Hanihara undoubtedly was well aware of Phelan and his ilk, particularly after 1916 when Hanihara began a tour of duty as Japan’s Consul General in San Francisco.[4] If Phelan tempered the expression of his views somewhat while Japan served as an ally during World War I, with the cessation of hostilities he came roaring back. Hanihara, meanwhile, was back in Washington after the war, continuing his meteoric rise through diplomatic ranks as part of the Japanese delegation to the Washington Naval Disarmament Conference, which was to take place in November 1921.[5] It was Phelan and not Hanihara who took a keen interest in the Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920.

Revisiting the Chinese Exclusion Act (First Attempt)

As early as 1917, the Hawaii Sugar Planter’s Association (HSPA) had already decided that the long-term solution to their problems with the intractable Japanese laborers was to resume the mass importation of the Chinese. In their minds, the problem was that, with the U.S. annexation of Hawai’i in 1898, they had been forced to conform to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and thereby resort to the Japanese, who were simply too racially cohesive and nationalistic to stay at work on the plantations without forming troublesome unions. The Chinese, by contrast, they would later tell the U.S. Congress,

are wonderful agricultural pacemakers. Experience has proved that they make splendid American citizens. No more desirable offshoot of an alien race is to be found in Hawaii today than the generation of Chinese born here in Hawaii. There is no racial solidarity among them that breeds hostility to the government under which they live.[6]

On February 28, 1920, the U.S. Senate Committee on Immigration and Naturalization met privately with Charles J. McCarthy, the territorial governor of Hawai’i, the topic being “the Japanese in Hawaii.” Senator Phelan, who was on that committee, was not terribly interested in the positive attributes of Chinese immigrants but was very keen to hear more about the Japanese, including the possibility that the sugar strike was being directed by the Japanese government through its consulate in Honolulu:

I have read in the Hawaiian Pacific Commercial Advertiser that there is a great strike going on now in the islands, and that the Japanese have formed unions, and that in order to coerce the men to join the union and engage in the strike, that they have threatened to report their names to the burgomasters of their cantonment at home in Japan, which probably would entail severe penalties on their families. . . . That seems to be a favorite method with the oriental, to punish the family of the man doing wrong.[7]

McCarthy replied that the strike was confined to the island of Oahu and that the Japanese government had denied any involvement with it.

But Senator Phelan pressed on: "I see that there was a Japanese warship came into the harbor out there the other day, was there not?" McCarthy replied that he had learned of the arrival of the Japanese warship Yakumo from the Washington newspapers as well, but he could not say why the ship had put in to port. Phelan responded in irritation, "I understood it came in to take off the Japanese. . . . " The chairman interrupted Phelan to call a recess, perhaps because he felt that Phelan was talking too much about U.S.-Japan relations…

The meeting finally turned to the expansion of the American army and navy bases in Hawaii. When Governor McCarthy observed that 90 percent of the construction workers on these bases were Japanese, the senators were shocked. "Are they employed in simple construction work or are they employed in gun emplacement?" asked Phelan. McCarthy responded that Japanese laborers were needed to build "actual fortifications, gun emplacement, etc.," but that the responsibility lay with the U.S. Engineer's Office.

"You say that [the Japanese] were employed in the building of the first Pearl Harbor dry dock?" asked Phelan.

"Yes sir."

"Well, is it not a fact that the dry dock collapsed?"

"Well, that was through the fault of the specifications."

"You think so?"

When other members of the Hawaiian delegation raised doubts about whether Japanese laborers had worked on gun emplacements, Phelan cut them off. "Well, it is immaterial who builds the fortifications, so long as we have 120,000 aliens owing foreign allegiance—in case of trouble with Japan they could take the fortifications and massacre the native population without trouble, could they not?"[8]

Military Intelligence, the BOI, and the Hearst Newspapers Step In

As noted earlier,

the Justice Department under A. Mitchell Palmer had taken a keen interest in the Oahu Sugar Strike and kept tabs on developments through the U.S. Attorney for the District of Hawai’i, eventually putting pressure on the HSPA to end the strike that June. By the beginning of 1921, not only was Palmer’s political career at an end, Senator Phelan had also been voted out of office. But this did not end the matter of the Japanese “threat” to Hawai’i, certainly not in the eyes of J. Edgar Hoover, who had somehow avoided the taint of the 1920 Palmer raids, which he had helped engineer, and was now thriving as the head of the Bureau of Investigation (BOI) under President Warren G. Harding (if you don’t remember how all that happened, I covered it in this post, towards the end).

The BOI had no jurisdiction over the territory of Hawai’i—yet—but it did have branch offices in Los Angeles and San Francisco who were willing to report on it. The BOI also was somehow still able to draw upon reporting from what remained of the U.S. wartime military intelligence apparatus.

The Military Intelligence Division (MID) that Colonel Ralph van Deman had stood up so rapidly upon U.S. entry into World War I (which I discussed here:)

had just as rapidly declined in size and status under the peacetime Army. But it hadn’t gone away entirely, particularly its counterintelligence capacity. Van Deman had led a group of 60 counterintelligence (CI) agents to provide security for the U.S. delegation at the 1919 Versailles Conference, and CI agents at home had transitioned seamlessly from the German to the Bolshevik threat, one agent opining that the United States was “verging on revolution.” General Pershing, who took over as Army Chief of Staff in 1921, generally de-emphasized the importance of intelligence during peacetime and also insisted that military intelligence take on responsibility for public affairs, as it had done with the American Expeditionary Force (AEF) in Europe. The result was that “intelligence work often became a dumping ground for officers incapable of performing any more demanding activities.” [9]

The U.S. Navy also had an Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) with a global system of naval attachés, including in Tokyo. These attachés collected and reported information to the ONI’s Foreign Branch, whose job was to produce information about all foreign navies. However, starting in 1920 and continuing until the late 1930s,

the Foreign Branch apparently concerned itself more with secondary objectives, such as military, political, economic, and sociological intelligence, which could have been provided by the Army's Military Intelligence Service, the Department of State, the Department of Commerce, and other government agencies.[10]

Some of either the Army’s or Navy’s reporting on the Pacific region made its way to the BOI, which on January 22, 1921, issued a report out of its Washington headquarters entitled “The Japanese problem in the United States.”

"The Japanese are physically a peculiarly constituted people," it reported. "It is known that they cannot stand either the extreme cold climate or the extreme hot climate. Therefore, it is not possible to extensively colonize the Japanese in Siberia or in northern China, neither is the colonization of Formosa or other equatorial land feasible." Hence the Japanese tried to emigrate to California, where the climate was ideal. "This peaceful penetration finally became obnoxious to California, who saw that ultimately if the Japanese were permitted to emigrate to the United States, the white race in no long space of time would be driven from the state, and California eventually become a province of Japan, as the Hawaiian islands are, practically, today until the entire Pacific Coast region would be controlled by Japanese."[11]

Ironically, despite Palmer’s and Hoover’s obsession with the domestic Bolshevik threat, this crack team of intelligence collectors had somehow failed to identify the one prominent Japanese immigrant leader who was a bona fide Communist. Sen Katayama, based in New York City, had been radicalized by a meeting there with Leon Trotsky in the spring of 1917 and had been serving as the primary liaison between Soviet Russia’s Comintern and Japanese socialists since 1919. Katayama and a coiterie of his fellow Japanese immigrants regularly translated Comintern and socialist literature from Russian into Japanese and spreading it on the Comintern’s “Western route” that ran between Amsterdam, New York and Mexico City.[12] For some reason, during the first Palmer raids of January 2, 1920, in which nearly 4,000 Communists and other radicals were rounded up, Katayama was not targeted for arrest.[13] He subsequently helped the Comintern establish a network of Japanese Communists on the East and West Coasts, as well as in Hawaii and Mexico, before departing for Moscow in 1921, from which vantage point he headed the global Japanese Communist movement until his death in 1933.[14]

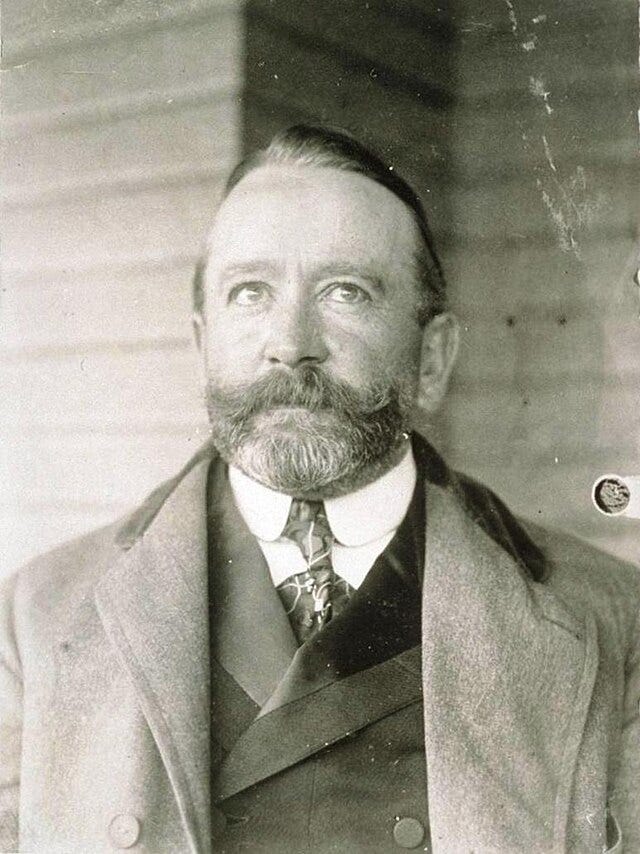

Instead, the BOI prepared an extensive profile of Noboru Tsutsumi, the former school principal turned labor organizer, as the first of its weekly series of reports on Japanese affairs in Hawai’i.[15] The BOI’s Los Angeles branch maintained an investigative file on Tsutsumi, describing him as

one of the leaders of the Japanese Federation of Labor [who] is considered by Informants as a very dangerous agitator and a Radical Socialist. He is highly educated in Japanese, being a graduate of the Imperial University at Tokio [mistake for Kyoto Imperial University]...He is a very fluent speaker, very radical in his views. The laborers at present worship him like a god and believe whatever he tells them.[16]

The BOI considered the Japanese Federation, in turn, to be “a weapon in Japan's strategy to take over Hawaii. The Japanese engaged in a radical labor movement as a means and weapon of national and racial policies to dominate the Hawaiian islands economically and politically. The Federation was an example of the frightening unity and teamwork of the Japanese.”[17]

By then, news of the Oahu sugar strike and various other goings-on among the Japanese immigrant community in Hawai’i had become the latest obsession of the Hearst newspaper chain—the same chain that had done its level best to instigate the Spanish-American War of 1898—with a March 1921 series in the Los Angeles Examiner that led off with the headline "Jap Menace Lies Black on Pacific!"

"Hawaii," the paper proclaimed, "is a menacing outpost of Japan ruled invisibly by a carefully organized government that functions noiselessly and whose mainspring is in Tokio." A political cartoon accompanying the article showed the black shadow of a Japanese soldier with a sword spreading across the Pacific Ocean. His military cap nearly touches the West Coast, and the words "Hawaiian Islands" are etched where his heart would be…

The third in the series reported breathlessly,

The sordid facts are that geishas are prostitutes and tea-houses are houses of assignations…This popularity of the geisha and tea-house institution is symbolic of the character of the Japanese population of the islands…As in Japan, pleasuring and politics and business revolve around the geisha. Banquets are held in the tea-houses. Geishas, not the wives, are the companions of the banqueters…Two thousand nine hundred geishas and helpers are listed in the Japanese Consul General's tables of occupations of Japanese in the Hawaiian islands in 1919…When labor delegates came into Honolulu from the other islands last year, disposed in part to oppose the strike, they were banqueted and given over to the seductive charms of the geishas. The geishas promptly brought them into line.[18]

None of this reporting mentioned the role of Pablo Manlapit or the young, male, restless, sex-starved, machete-wielding Filipinos who had actually started the strike and then physically intimidated the Japanese field laborers into going along with it.

Revisiting the Chinese Exclusion Act (Second Attempt)

In April 1921, the HSPA created a “Hawaii Emergency Labor Commission” to return to Washington for a second pass at legalizing the importation of Chinese coolie labor, meeting with President Harding in May and then testifying before the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization in June and July and the Senate counterpart in August. If the plan was to increase support for Chinese immigration to Hawai’i as a preferable alternative to the Japanese, it did not go well. The AFL continued to strongly oppose Chinese immigration and denounced the planters for trying to hire “the most easily exploited workers.”[19] The head of the American Sugar Beet Company, who was based in California and used Mexican Bracero laborers, insisted that the Hawai’ian sugar planters were simply trying to undercut him on labor costs and queried why they couldn’t just bring in more Filipinos, since the Philippines were U.S. territory.[20]

The HSPA witnesses, however, were phenomenally successful at continuing to ramp up paranoia about the Japanese. They testified that the sugar strike had been the result of a Japanese conspiracy to create a “Little Japan” in Hawai’i, even going so far as to suggest that it had been timed to coincide with an effort by Japanese buyers to purchase the Olaa Sugar Plantation. Prince Kuhio Kalanianaole, the elected delegate to Congress from the territory of Hawai’i, repeatedly insisted that the Japanese had been plotting for many years to take over Hawai’i (a descendant of the branch of the Hawai’ian royal family that had once controlled Maui, Prince Kuhio did not mention the attempt of his ancestor King Kalakaua in 1881 to unite the Japanese Empire and the Hawai’ian Kingdom through marriage).[21]

The new Hawai’i territorial governor Wallace Farrington testified that the strike had “opened the eyes of a good many of us to a condition which has become more acute as time has gone on…It stands to reason, and I think that it appeals to all of us, that the main industry in any part of our country should not be in the hands of, or subject to the dictates of, an alien element, regardless of the origin of that people." Royal Mead of the HSPA testified that “without doubt, as a race, the absolute coherence and solidarity of the Japanese is marvelous,” and that it made no difference whether they were born in Japan or Hawai’i. [22]

Again, nobody mentioned the role of the Filipinos who had actually started the strike. Instead, the written petition from the Hawaii Emergency Labor Commission for the resumption of Chinese immigrant labor summarized the events as follows:

The intractability and hostility of the Japanese as a class toward the American community was forcefully demonstrated during a strike of Japanese plantation laborers on the island of Oahu during 1920. The strike, it has been sufficiently proved, was planned and fomented by the Japanese language press, the principals and heads of Japanese language schools, and the Buddhist priests…

There is no proof of charges that were frequently made during the strike that it had been called in obedience to orders from Tokio, but it is certain that some of the strike leaders led their followers to believe that such was the case. Many Japanese laborers were reluctant to strike, probably on account of the large wages and bonuses they were then receiving, and some few of them actually refused to strike. These latter were persecuted, abused, maltreated, even beaten and kidnapped by the strike leaders and their fundamental love of and respect for home, family and country were played upon to keep them in sympathy with the strike. During this strike, there appeared in the Japanese language newspapers, statements and advertisements to the effect that those recreant laborers who refused to go on strike would be reported to the municipal heads of their native towns in Japan so that their relatives living there might be ostracized and otherwise punished. In pursuance of this policy of intimidation, there appeared in the Japanese press lists of names of Japanese who had defied the strike leaders.[23]

The Great Oahu Conspiracy Trial

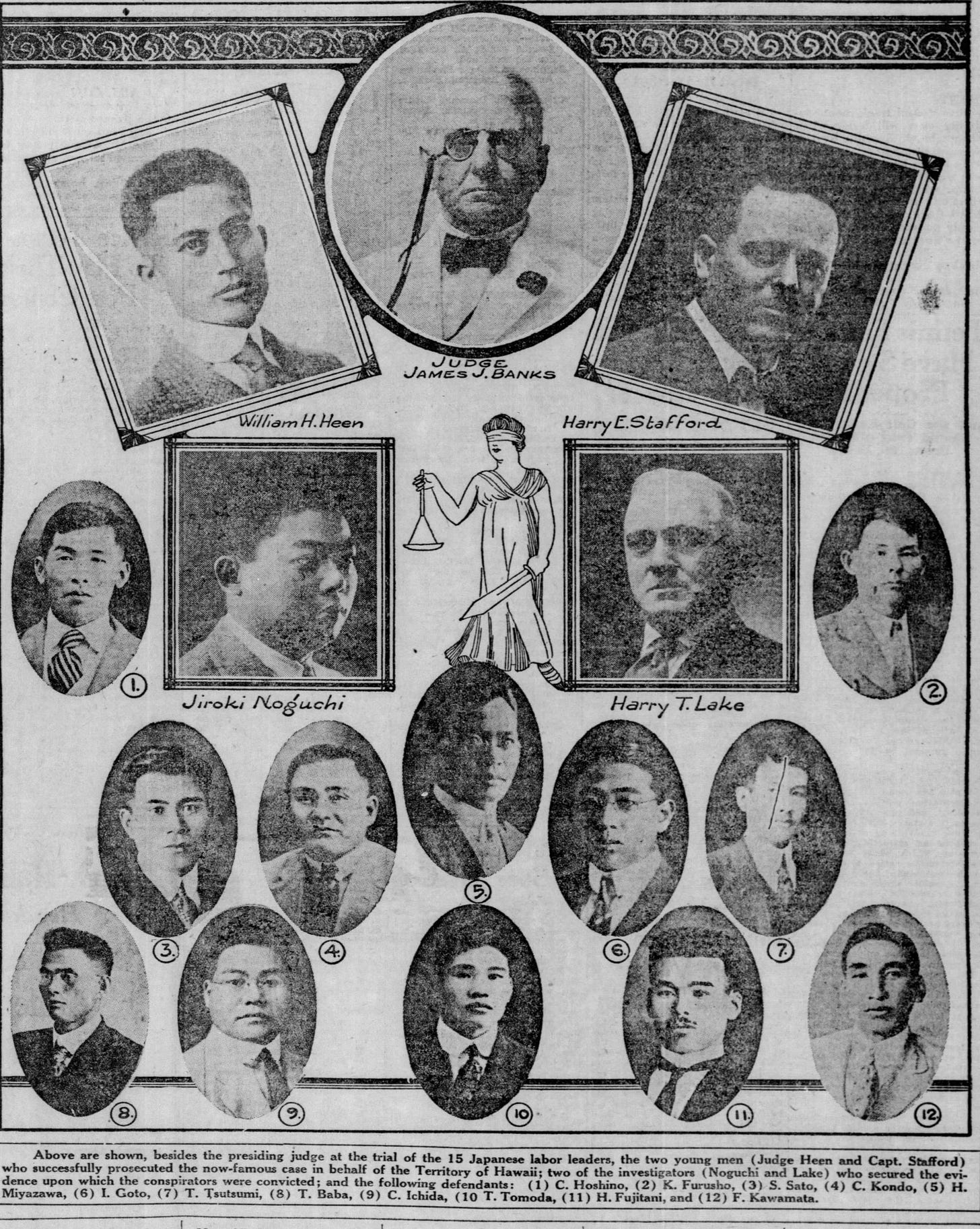

These efforts in Washington were then underscored by an indictment issued on August 1 out of Honolulu against 21 Japanese Hawai’ian defendants, all associated with the Japanese Federation of Labor, and all now accused of conspiring to assassinate the interpreter Frank Sakamaki by dynamiting his house. The Honolulu Advertiser summarized the indictment as follows:

On the night of June 3 [1920] a band of the 'assassination corps' forced an entrance into the house of a Japanese named Sakamaki, a plantation employee who had refused the join the strikers. While one member of the band stood guard with a drawn pistol, another deposited a quantity of dynamite under the house and then set off the fuse with a lighted cigarette, according to the evidence.[24]

Matsumoto, the knucklehead who had waited in the getaway car for this “assassination corps,” then attempted to collect his purported $5000 payout only to receive a smackdown at the Kyorakukan restaurant, thereafter confessing his own involvement to the police, was now the star witness for the prosecution, all while living on the grounds of and working for an HSPA lawyer named Frank Thompson.[25] The 27-year-old Saito, who had ridden in the car and then gone with Murakami to plant the dynamite, was also a prosecution witness. Murakami was one of the 21 defendants. Kaichi Miyamura, however, the one person who had explicitly given the order to kill Sakamaki (allegedly), had long since returned to Japan. At the time of the indictment, the prosecution announced that it would ask the Japanese government to extradite Miyamura, but it never actually made a formal request.[26]

Instead, the prosecution focused on proving an assassination conspiracy on the part of the entire roster of Japanese Federation leadership, starting with Tsutsumi.

The 15 defendants who actually stood trial also included Goto, Miyazawa, Kawamata, Furusho, Takizawa, Baba, Tomota, Ishida, Koyama, Kondo, Sazo Sato, Fujitani, and Murakami. Matsumoto, reading from notes while on the witness stand, implicated all of them as having ordered the killing, despite the fact that none of them, besides the absent Miyamura, had either directed him to kill Sakamaki or offered him $5000 for doing so.[27] There was also no evidence introduced either that Sakamaki had received threats prior to the incident (Sakamaki also testified),[28] or that he was perceived by the Federation as a particularly important or influential player.[29] Miyazawa testified that Sakamaki was a longtime good friend of his and that he had not been present at any meeting at which Sakamaki had been discussed.[30]

The all-white jury had difficulty telling the defendants apart and ended up finding all of them guilty after five hours of deliberations.[31] In the meantime, the testimony had produced some sensational news headlines, such as when Seiichi Suzuki, the procurer of the dynamite and now a prosecution witness, initially testified that he had obtained six sticks of dynamite but then contradicted himself, saying that actually, he had obtained thirty sticks and had his brother send it to him in Honolulu by mail. For those who followed the press coverage of the trial, the enduring impression of the Japanese “threat” to Hawaii was likely exemplified by the resulting headline in the Honolulu Advertiser: "Dynamite Sent by Mail Says Witness, Enough High Explosives to Destroy Steamer Brought from Maui to Honolulu."[32] On March 10, 1922, the defendants were all sentenced to imprisonment in Oahu prison at hard labor for “not less than four years nor more than ten years.”[33]

You said something earlier about Hanihara attending a Washington Naval Disarmament Conference, what was that all about?

Indeed, the up-and-coming Japanese diplomat Hanihara, posted to Washington, was at the time of the trial in Hawai’i mostly preoccupied with supporting Japan’s delegation to the seminal Washington Naval Disarmament Conference, which took place between November 1921 and February 1922. The goal of this conference—depending on who one asked—was to address growing anxieties about a naval arms race between the three top global naval powers: Britain, Japan, and the United States. The United States in particular, which had refused to join the League of Nations after the Versailles Conference of 1919, was perceived by Britain as not only a threat to world peace, but as vying to surpass the British Empire’s global naval supremacy through shipbuilding, on a scale that Britain could no longer afford amid the deprivation and war debts accumulated during World War I.[34] In preparation for the naval conference, to which the United States invited Britain in August 1921, a memorandum prepared by the Royal Navy’s intelligence staff “depicted US naval policy as a titanic struggle between public opinion and Congress on the one hand, seeking substantially to reduce expenditure on naval and merchant marine construction, and, on the other, an administration bent on completing the 1916 naval programme [initiated by President Wilson] and achieving supremacy at sea.”[35]

The Anglo-Japanese alliance, in effect since the Japanese victory over Russia in 1905, could have, in theory, served as a counterweight to U.S. ambitions. Japan’s first super-dreadnought, the battlecruiser Kongo, had been designed and built in Britain in 1913,[36] and Britain continued to supply Japan with naval aircraft through the early 1920s. However, the alliance was not only provocative to the United States, it was deeply unpopular with several British Dominion powers. Australia, in particular, which had insisted upon the rejection of Japan’s racial non-discrimination language at the 1919 Versailles Conference, saw “imperialist, expansionist Japan, seeking to divide Britain from the United States, as the urgent threat to Australian security. Japan, sprung loose by arms limitation in the Pacific and by the relinquishing of British and American offensive naval forces and bases, would pursue interests, including the domination of China, that threatened those of the white races.”[37] Canada, as well, was deeply influenced by racial factors, as “the Japanese population of British Columbia was so unpopular that British Columbia, its public attitudes mirroring those of California, would not expect Canada to be neutral” in a war between the United States and Japan.[38] Finally, the British consul in Yokohama, who collected intelligence for the Indian political intelligence service, was reporting “latent Japanese hostility to the British Empire through its support for Indian extremists,” which led the Foreign Office, and especially Curzon, a former viceroy of India, to argue against renewing the Anglo-Japanese alliance.[39]

The practical reality for the United States, which is why it convened the Washington Conference, is that the U.S. Navy lacked popular or Congressional support for such a massive buildup. By February of 1920, 14 of the 16 capital ships planned under President Wilson’s 1916 program were completed, with two more to be begin shortly.[40] The U.S. Congress, however, was increasingly unwilling to fund a naval arms race. On December 14, 1920, Senator William Borah of Idaho introduced a resolution requesting the President to call a conference that would end naval competition. When he re-introduced it in April 1921, it passed, and with President Harding unable to block it and public support behind the measure readily evident, Harding was essentially forced to convene the Washington Conference, although he made a point of ensuring that all the credit for it was attributed to his administration. Outreach to the British through Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes began shortly afterwards.[41]

While President Wilson’s 1916 program was focused on achieving naval parity with Great Britain, hoping that the mere threat of a big naval program would force Britain to support his peace agenda,[42] the U.S. Navy’s strategy for the upcoming conference was now laser-focused on Japan. Between July and September 1921, guided largely by Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., the Navy General Board analyzed Japan’s institutional structure, and decided that the “Japanese governing classes [were] militaristic with feudal traditions; consequently the Japanese Government [was] aggressive.”[43] Secretary Hughes came to much the same conclusion about Japanese intentions, based on the SIGINT being collected by Herbert Yardley’s Black Chamber, which had somehow survived the peacetime cuts to Van Deman’s Military Intelligence and was now established at a secret address in Manhattan, jointly funded by the Departments of War and State, and proving itself quite successful at intercepting Japanese diplomatic traffic.[44]

(Remember Herbert Yardley? I discussed him here:)

Japan’s intentions in the Pacific mattered greatly to the United States, which was still at that point heavily wedded to the Open Door policy. “The American attitude toward China in the 1920’s was shaped by the magic statistic—400,000,000 Chinese—and by the belief that the American industrial plant was turning out more than could be absorbed in the home market.”[45] Moreover, while American business interests and Americans as a whole were still somewhat ambivalent or even wholly disinterested in continued American sovereignty over the Philippines, until at least the mid-1930s, they continued to persist as

the embodiment of a commercial dream. As our policy toward China was built upon the magic statistic of 400,000,000 potential consumers and souls to be saved, so our policy toward the Philippines was built upon the premise that they would be an entrepôt in the Oriental trade, and that their inhabitants would likewise become consumers and Christian neophytes. Unforeseen by many, and eagerly accepted by others, was the hard fact that possession of those verdant isles meant a plunge into the morass of Far Eastern politics, and a part of this new responsibility would be the commitment to their defense.[46]

President Harding’s appointed Governor-General of the Philippines, General Leonard Wood,

(Remember Leonard Wood? I last discussed him here; he was Theodore Roosevelt’s commanding general during the 1898 invasion of Cuba):

strongly opposed independence for the Philippines and believed that their defense required, among other things, that the island of Oahu be made “impregnable” through the military buildup at Pearl Harbor.[47]

Where did this leave the Japanese, whose diplomatic traffic was being intercepted not only by Yardley’s Black Chamber, but also the British Government Code and Cipher School (GC&CS) that had replaced the Royal Navy’s “Room 40” as its lead cryptographic unit in 1919?[48] What the United States failed fundamentally to understand, notwithstanding its advantages in SIGINT, was that Japan’s access to China was not a commercial pipe dream, but a matter of survival.

Japanese concentration on industry had created an urbanized economy that bought imported food and raw materials with exported manufactured goods. A sudden change in the China market could mean possible starvation in Japan…These economic facts of life caused increased pressures on the Chinese to keep them within the Japanese economic orbit, and Japanese interference in Chinese affairs to assure that internal chaos did not ruin an all-important market…

Simply stated, Japanese and American national policies, though basically pointing toward similar national objectives; i.e., capturing the Far Eastern markets, clashed due to the relative importance of subsidiary policies. Their Far Eastern markets were a matter of life or death to the Japanese, and as a result of this realization they built a navy capable of supporting their policies in Far Eastern waters. This navy, unfortunately, was strong enough to menace American possessions in Guam and the Philippines. The United States, on the other hand, demanded absolute equality with the Japanese in the Far East, though its interests were in no way equal.[49]

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) had its own nascent intelligence-gathering capacity, and in October 1920 obtained a copy of a confidential U.S. Navy war plan for a trans-Pacific offensive. From this document, the IJN concluded that the U.S. Navy required at least a three-to-two superiority over Japan in order to advance its main fleet to the western Pacific and impose an economic blockade.[50] Accordingly, IJN Vice Admiral Kato Kanji, who served as the Navy expert on the Japanese delegation to the Washington Conference, considered it an issue of survival as well as national honor to pursue 1:1 parity with the U.S. Navy fleet of capital ships, and certainly accept no less than a 10:7 ratio.[51]

Kato Kanji, however, was not the head of the delegation; that job fell to the Navy Minister, Kato Tomosaburo, a future Prime Minister, who understood that chasing naval parity with the United States, particularly given Japan’s postwar recession (remember the rice riots of 1918?), would only spell financial ruin for Japan; he had admitted as much at a budget committee of the Diet in February 1919.

For him, the invitation to the Washington Naval Disarmament Conference must have seemed like a godsend. And when Secretary Hughes opened the conference with the dramatic bid for a reduction in capital ships according to a 10:10:6 ratio (United States, Britain, Japan), Kato Tomasoburo almost immediately decided that Japan had no choice but to accept it. Although he pushed for a 10:10:7 ratio, one of his priorities was to improve Japanese-American relations, and at any rate, he genuinely believed that the question of the United States’ advance bases in the Philippines and Guam was more crucial to Japan’s Pacific strategy than “hairsplitting bargains over fleet ratios.”[52]

For Kato Kanji, the 10:10:6 ratio was nothing less than national humiliation, strategic ruin, and obvious “Anglo-American oppression,” setting off a power struggle between the two Katos during the course of the conference. When the elder Kato, having heard and debated Kato Kanji’s impassioned arguments, summarily overruled him, the junior Kato promptly went behind his superior’s back, cabling back his dissenting views to naval authorities in Tokyo. What the junior Kato didn’t know was that the senior Kato had already conveyed the senior Kato’s dissent directly to his Vice-Minister, Ide Kenji, and obtained the approval of the Government and Fleet Admiral Togo, for his decision to accept the 60 per cent ratio.[53] What neither of the Katos knew was that all this top-secret cabling back and forth between Washington and Tokyo was being intercepted, decrypted and passed to the U.S. delegation by Herbert Yardley’s Black Chamber in Manhattan. Years later, Yardley would brag in his tell-all book American Black Chamber that the instructions to Kato from Tokyo directed him to push for a 10:10:6.5 ratio but also authorized him to accept a 10:10:6 ratio in exchange for a guarantee that the United States would maintain the status quo of Pacific defenses. As Yardley asserted, “With this information in its hands, the American Government…[needed only] to mark time. Stud poker is not a very difficult game after you see your opponent’s hole card.”[54]

Thus, the Washington Conference concluded in February 1922 with an agreement to maintain a 10:10:6 ratio in capital ships, widely perceived in the United States as a foreign relations coup for the Harding Administration, not to mention a new dawn for positive Japanese-American relations. In Washington, Hanihara’s star rose yet further, as he had had to take on a more senior role supporting Kato Tomosaburo’s delegation after the Japanese Ambassador to the United States, Shidehara Kijuuroo, became seriously ill. A liberal thinker in the field of international relations, his approach gelled naturally with the elder Kato’s desire to improve relations with the United States. By December 1922, the beloved “Hany,” still only 46 years old, succeeded Shidehara as the Japanese Ambassador to the United States.[55]

But not all was as it seemed beneath the surface.

On the day Japan accepted the 60 per cent ratio, Kato Kanji was seen shouting, with

tears of chagrin in his eyes, 'As far as I am concerned, war with America starts now. We'll get our revenge over this, by God!' Thus the political decision to accept the compromise settlement failed to take root in Japan's subsequent naval policy; on the contrary, the reaction from naval men, if anything, reinforced their obsession with the 70 per cent ratio and their notion of the United States as the hypothetical, even inevitable, enemy.

Kato Tomosaburo, who wished to pursue institutional reforms that included civilian control of the IJN, was to become Prime Minister in June 1922 in recognition of his performance at the Washington Conference but would die a little over a year later of late-stage colon cancer. Kato Kanji, who had been promoted to Vice-Chief of the Naval General Staff in May 1922, was able to counter any further civilian reform of the IJN, and in February 1923, the Navy and Army General Staffs adopted a new, combined national defense policy, which singled out the United States as the common “hypothetical enemy” number one, replacing Russia.[56]

The IJN also, along with the Japanese Army, began to beef up their intelligence-gathering through the Army’s Second Bureau and the IJN’s Third Bureau, as the latter believed they had been outmaneuvered by their British and American counterparts at the Washington Conference.[57]

The Washington Conference’s limitation on a naval arms race with respect to only capital ships also left open the possibility of a race to build and deploy every other conceivable type of ship, which is exactly what the three major naval powers promptly proceeded to do, and which would not begin to be addressed until the Geneva Naval Conference of 1927.[58] (A special thanks to Toni Mikec for explaining this to me). In addition, the elder Kato was not wrong that maintaining the U.S. status quo on fortification of Pacific base defenses potentially mattered more to Japan than the ship ratio. Japan, having acquired the islands of Tinian, Saipan, and Truk at the Versailles Peace Conference, was already militarizing them,[59] British intelligence having picked up on the fact that they were in fact scrambling to complete fortifications on these islands in time for the conference so that they could then argue in favor of committing to the “status quo.” The United States, now committed by treaty to building no further fortifications in Guam, the Philippines or elsewhere west of Hawai’i, was relegated to fortifying its bases along the Pacific coast, most notably San Francisco, as well as, or of course, Pearl Harbor. The IJN was to use their advantage in western Pacific bases to huge effect in World War II.

To be continued…

Does all this suffice to explain, as per my promise to my wife, how the Great Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 connect to absolutely everything else in my scholarship? No. But that’s because we haven’t yet talked about the 1924 Immigration Act and the dramatic fall from grace of Ambassador Hanihara. Stay tuned!

[1] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 67.

[2] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 73.

[3] Quoted in Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 235-36.

[4] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 83.

[5] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 89.

[6] Hawaii Emergency Labor Commission, “"The Sugar Industry of Hawaii and the Labor

Shortage—What it means to the United States and Hawaii," summary statement provided to the House Immigration and Naturalization Committee, June 21, 1921, quoted in Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 232.

[7] Quoted in Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 235-36.

[8] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 236-38.

[9] Quoted in John Patrick Finnegan, Military Intelligence (Center for Military History, U.S. Army, Washington, DC, 1998), Chapter 3, available at https://web.archive.org/web/20071213202943/http://www.history.army.mil/books/Lineage/mi/mi-fm.htm (viewed May 13, 2025).

[10] Captain Wyman H. Packard, A Century of Naval Intelligence (Office of Naval Intelligence and Naval Historical Center, U.S. Department of the Navy, 1996), at 14, available at https://ncisahistory.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/A-CENTURY-OF-US-NAVAL-INTELLIGENCE-compressed.pdf (viewed May 13, 2025).

[11] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 241.

[12] Tatiana Linkhoeva, Revolution Goes East: Imperial Japan and Soviet Communism (Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London: 2020), at 160.

[13] Hyman Kublin, Asian Revolutionary: The Life of Sen Katayama (Princeton University Press: 1964), at 271-72. Available at https://archive.org/details/asianrevolutiona0000unse/page/n5/mode/2up (viewed May 14, 2025).

[14] Tatiana Linkhoeva, Revolution Goes East: Imperial Japan and Soviet Communism (Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London: 2020), at 161.

[15] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 241.

[16] National Archives, Investigative Case Files of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, January 28, 1921 , report on Japanese Affairs (Honolulu and Hawaii Islands); referring to Los Angeles Weekly Intelligence Report for January 13, 1921, pp. 26, 27, 28, quoted in Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 27-28.

[17] National Archives, Investigative Files of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Japanese Affairs (Honolulu and Hawaiian Islands), Report dated February 5, 1921, quoted in Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 220-21.

[18] Quoted in Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 238.

[19] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 259.

[20] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 260-61.

[21] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 268, 273. I discussed King Kalakaua’s visit to Japan in this post: https://laraballard.substack.com/p/the-great-oahu-sugar-strike-of-1920).

[22] Quoted in Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 254-55.

[23] Quoted in Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 254-55.

[24] Quoted in Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 139-40.

[25] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 166.

[26] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 152.

[27] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 149.

[28] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 145.

[29] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 220.

[30] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 183.

[31] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 225.

[32] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 175.

[33] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 226.

[34] Michael Graham Fry, “The Pacific Dominions and the Washington Naval Conference, 1921-22,” in Erik Goldstein and John Maurer, eds., The Washington Conference, 1921-22: Naval Rivalry, East Asian Stability and the Road to Pearl Harbor (Taylor & Francis Group, 1998), at 73.

[35] Id. at 79.

[36] Andrew Boyd, British Naval Intelligence Through the Twentieth Century (Seaforth Publishing, 2020), at 266.

[37] Michael Graham Fry, at 78.

[38] Id. at 80.

[39] Andrew Boyd, British Naval Intelligence Through the Twentieth Century (Seaforth Publishing, 2020), at 264.

[40] Andrew Boyd, British Naval Intelligence Through the Twentieth Century (Seaforth Publishing, 2020), at 273.

[41] Gerald E. Wheeler, Prelude to Pearl Harbor: The United States Navy and the Far East, 1921-1931 (University of Missouri Press, 1963), at 53.

[42] Andrew Boyd, British Naval Intelligence Through the Twentieth Century (Seaforth Publishing, 2020), at 270.

[43] Quoted in Gerald E. Wheeler, Prelude to Pearl Harbor: The United States Navy and the Far East, 1921-1931 (University of Missouri Press, 1963), at 53.

[44] Christopher Andrew, The Secret World: A History of Intelligence (Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 2018), at 586.

[45] Gerald E. Wheeler, Prelude to Pearl Harbor: The United States Navy and the Far East, 1921-1931 (University of Missouri Press, 1963), at 6.

[46] Gerald E. Wheeler, Prelude to Pearl Harbor: The United States Navy and the Far East, 1921-1931 (University of Missouri Press, 1963), at 12.

[47] Gerald E. Wheeler, Prelude to Pearl Harbor: The United States Navy and the Far East, 1921-1931 (University of Missouri Press, 1963), at 14.

[48] Andrew Boyd, British Naval Intelligence Through the Twentieth Century (Seaforth Publishing, 2020), at 257, 276.

[49] Gerald E. Wheeler, Prelude to Pearl Harbor: The United States Navy and the Far East, 1921-1931 (University of Missouri Press, 1963), at 31.

[50] Sadao Asada, “From Washington to London: The Imperial Japanese Navy and the Politics of Naval Limitation, 1921-1930,” in Erik Goldstein and John Maurer, eds., The Washington Conference, 1921-22: Naval Rivalry, East Asian Stability and the Road to Pearl Harbor (Taylor & Francis Group, 1998), 150-191, at 152.

[51] Sadao Asada, “From Washington to London: The Imperial Japanese Navy and the Politics of Naval Limitation, 1921-1930,” at 154.

[52] Sadao Asada, “From Washington to London: The Imperial Japanese Navy and the Politics of Naval Limitation, 1921-1930,” at 154.

[53] Sadao Asada, “From Washington to London: The Imperial Japanese Navy and the Politics of Naval Limitation, 1921-1930,” at 155.

[54] Herbert O. Yardley, The American Black Chamber (The Bobbs-Merrill Company: Indianapolis, 1931), at 313, available at https://archive.org/details/american-black-chamber-ii-watermark/mode/2up (viewed May 23, 2025).

[55] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 90-98.

[56] Sadao Asada, “From Washington to London: The Imperial Japanese Navy and the Politics of Naval Limitation, 1921-1930,” at 156-57.

[57] Richard J. Samuels, Special Duty: A History of the Japanese Intelligence Community (Cornell University Press, 2019), at 47.

[58] Sadao Asada, “From Washington to London: The Imperial Japanese Navy and the Politics of Naval Limitation, 1921-1930,” at 160-61.

[59] Margaret MacMillan, Paris 1919: Six Months that Changed the World (Random House, 2003), at 403-04, available at https://bnk.institutkurde.org/images/pdf/EJNCB23UK7.pdf (viewed May 2, 2025).