Giving them the finger

Part 3 of 3 on colonialism, immigration, and the origins of identity intelligence; this week: facial photographs and fingerprints.

In last week’s post,

I continued to explain the technological innovations that enabled the efficient collection and retrieval of personally identifiable information (PII) that today form the basis for what the U.S. intelligence community calls “identity intelligence.” I covered only library science and the filing cabinet, leaving photographic images and fingerprinting for a future post, so as not to make last week’s post, in the immortal words of my wife, “too long.”

Well, she’s also sure to complain that this week’s post is “too long,” but here’s the thing—in untangling the various threads of immigration policy, diplomatic relations, law enforcement, labor relations and colonial administration that run through World War I, I found something that no historian apparently has ever explored: the possibility that the United States’ now-notorious wartime “enemy alien” policy was modeled after Canada’s. With a little more digging in the U.S. National Archives and perhaps some help from a Canadian collaborator with access to archives in Ottawa, I could likely confirm this hypothesis and turn it into a standalone article.

In the meantime, I’m going to subject you all to what I have been able to figure out in the course of a week, and if you stick with me to the end, you’re going to be reunited with a familiar American face and a truly money quote about him.

But first, let’s establish how this all ties back to colonialism.

In 1858, Sir William James Herschel, chief administrator of the Hooghly district of Bengal, entered into a contract with Rajyadhar Konai to supply the building material for a road leading into the village of Jangipur. Konai was just about to sign the contract in the usual way, when, according to Herschel’s account, “I stopped him in order to read it myself; and it then occurred to me to try an experiment by taking the stamp of his hand by way of signature instead of writing.”[1]

In doing so, Herschel was well aware of the pre-colonial Bengali practice of tep-sai, by which illiterate individuals had long signed contracts by dipping a fingertip in ink and then applying it to the page; the term purportedly arose from two words meaning “pressure by touch or grip” and “token”[2] (there is a similar Chinese tradition of signing contracts with fingerprints dating back to the Tang Dynasty (618-907 A.D.)).[3] But Herschel began to see fingerprints as serving an entirely different purpose. As he studied them, as more or less an obsessive hobby over the next 20 years, he came to realize that a person’s fingerprint does not change over time.

This gave it enormous potential advantages over the photograph. While photography “is often considered the quintessential technology of modernity because of its assumed scientific veracity as an image type,” its significant limitation as a personal identifier, even when standardized as a portrait or “mug shot,” is that ultimately does not “convey anything more than the momentary appearance of the subject, with an ultimate reliance on text to explain the image.”[4]

As I noted in my 2013 law review article The Dao of Privacy, Western metaphysics in general posits that absolute knowledge is possible with regard to understanding the independent nature and properties of individual objects. British epistemology of the 19th century, with specific regard to Britain’s colonial subjects, was no different, part of the overall Western endeavor, exemplified as well by Bertillonage, of “transforming the human body from an inscrutable image into a quantifiable body of data.” [5] British authorities operated under the assumption that they both could and needed to perfect their knowledge about their colonial subjects through a sort of taxonomy, using visual representations of the body as an individual object. The effort was driven by a heightened anxiety that had taken hold after the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857-8, with concerns about the risks of forgery particularly high. “Colonial administrators believed they had little power to prevent Indians from impersonation and that Indians would ignore their contractual obligations entirely by slipping into anonymity, since signatures could be faked and did not provide a solution for holding the illiterate to their contracts.”[6]

Within the penal system, the very practical limitation of photography was that

“[m]ost convicts were photographed only at their initial entrance and exit and the identities of the inmates were never verified using the photographs during the actual sentence, meaning that there was no way to be sure that the right person was indeed serving the sentence. Photography only exacerbated the problem of governing people who were visible, but simultaneously unidentifiable and unfamiliar because a batch of unidentified images of native subjects remained inscrutable without textual records. An archive was also impossible to manage; finding enough employees to identify the photographs was difficult because many British officers were unwilling to employ Indians in this task.”[7]

The limitation on fingerprints was that there was no way to index them by type. Unless the fingerprint was already definitively associated with one person’s and only one person’s name, such that they could be organized in, say, alphabetical order, it was impossible to file and then retrieve them out of a filing cabinet—that is, until the 1890s, when two Bengali police Sub-Inspectors named Qazi Azizul Haque and Hem Chandra Bose worked out a mathematical formula for their classification.

Haque and Bose observed that 60 percent of all fingerprint patterns are loops, 35 percent are whorls, and only 5 percent are arches. Since so few patterns are arches, they combined arches and loops, leaving only two categories for finger ridges: L: Loops/Arches, and W: whorls. All ten fingers were then grouped by pairs: right index/right thumb, right middle/right ring, left thumb/right little, left middle/left index, and left little/left ring.

For each of these pairings, there were four possibilities; e.g., right index finger could be either L or W, and right thumb could be either L or W. Thus, the total number of possibilities were 4 x 4 x 4 x 4 x 4 = 1024. The square root of 1024 is 32, so if a criminal record room had 32 cabinets, and each cabinet had 32 files, each of the 1024 permutations could be given a numerical value, such that an official searching for a particular combination of fingerprints would be able to figure out that this pattern could be found, e.g., in the 2nd file of the 17th cabinet.[8]

Haque and Bose took this innovation to the Inspector General of the Police in Bengal, Sir Edward Henry. Henry reportedly had difficulty understanding the mathematics, but he at least understood its implications and knew how to promote it. On June 12, 1897, the Council of the Governor General of India approved a recommendation that fingerprints henceforth be used for criminal records in India; they were simple, cost-effective and more accurate than Bertillonage. That same year, the first Fingerprint Bureau in the world was established at Kolkata. In 1900 Henry was asked by the Identification of Criminals Committee “Is this system an invention of your own?” and Henry responded “Yes.” He returned to Britain in 1901, bringing “his” classification system with him to Scotland Yard, where he established a Fingerprint Bureau and became its Commissioner.[9] That is why the system is known today worldwide as the Henry Classification System.[10]

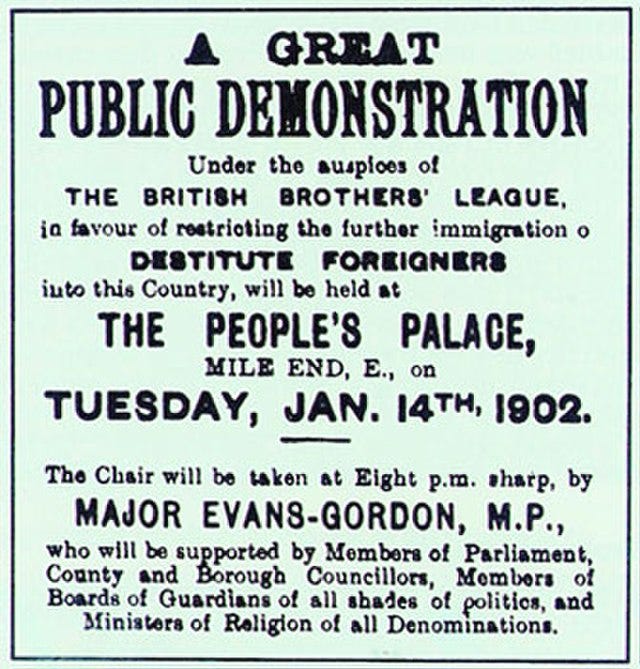

Fingerprinting arrived at Scotland Yard at a time when policymakers in the United Kingdom were looking with great envy at the U.S. Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and its progeny, along with similar regulations being enacted by the British Empire’s white colonial settlers throughout Australia, New Zealand and Canada.[11] The 1849 California gold rush had been one of only several worldwide that had brought a flood of Chinese prospectors, mostly Cantonese, to South Australia, New South Wales, and throughout New Zealand.[12] After the passage of the U.S. Immigration Act in 1891, many Chinese laborers and would-be immigrants to California instead began to migrate northward into British Columbia, where they found work in the coal mines.[13] White laborers in virtually all of these colonies had expressed xenophobic reactions to the Chinese, and many colonial authorities as early as the 1870s had enacted their own Chinese exclusion laws, along with a variety of other measures such as quarantine and health regulations, to keep out a range of immigrants deemed “undesirable,” not just non-whites.[14]

In the United Kingdom proper, by contrast, the political culture and national identity was one that long prided itself on free movement and “liberty,” providing a welcoming environment for political dissidents fleeing the more repressive regimes of Europe. The Russian pogroms of the 1880s and 1890s had prompted thousands of Jews to migrate to the United States via British ports, many of them settling in Britain instead, establishing a somewhat insulated but politically outspoken enclave in the East End of London (we can’t know exactly how many, since the UK imposed no registration or entry requirements of any kind).[15] As the United States cracked down on immigration, sending many of those denied entry right back to British ports,

“[i]n Britain, some restrictionists stressed the irony that the vast, under-populated and under-developed colonies relied on immigration, yet were nonetheless dictating who would be deemed a desirable immigrant and who would not be welcomed. By contrast, England was a small island with limited resources, an impoverished working class, a massive population and no economic need for mass immigration. Yet there were no laws or processes in place to prevent any amount of immigration, desirable or otherwise.”[16]

This political debate, tinged with anti-Semitism, eventually culminated in the Aliens Act of 1905, the first law ever passed in the United Kingdom to control immigration through border controls and institute alien registration, responsibility for which was given to the Home Secretary. But the Liberal Party, which took control of the government in 1906, sought to mitigate many of its effects in its implementation. The law contained one of the world’s first statutory rights to seek asylum, and Secretary of State Herbert Gladstone instructed immigration officers making portside decisions about immigrant admissions to afford the benefit of the doubt “in favour of immigrants who allege that they are flying from political persecution in disturbed districts.”[17] Fingerprinting of immigrants as a matter of course would not be implemented in the United Kingdom for a very long time.

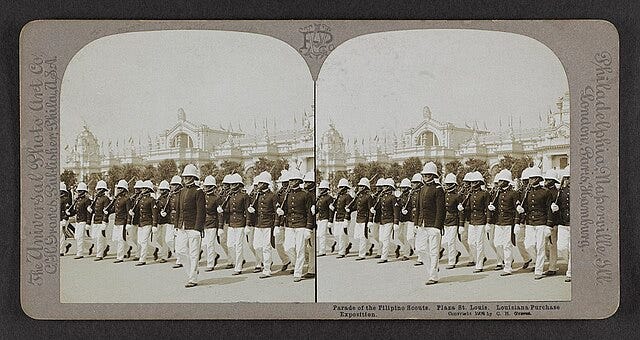

Instead, the “Henry” Classification System of fingerprints was being socialized worldwide through U.S. criminal justice and military channels. At the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri (known informally as the 1904 World’s Fair),

Scotland Yard sent a security contingent to protect the exhibit of Queen Victoria’s jewels, among them, Sergeant John K. Ferrier, who staffed a second exhibit and taught classes on fingerprinting. Attendees included Mary E. Holland, who ran her own detective agency in Chicago and whose husband published The Detective, a magazine for law enforcement professionals.

Holland was enraptured by Ferrier’s presentation and joined a group of nine Americans who studied with him for almost eight months.[18] She then traveled to London, where she passed proficiency tests administered by Scotland Yard. She quickly became one of the nation’s foremost experts on the Henry Classification Method, teaching it to the U.S. Navy, as the U.S. Army had started fingerprinting its recruits in 1905, and the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps quickly followed suit.

It is not clear what prompted the U.S. Army to adopt the practice; it may well have been seen as a more accurate means of identifying bodies on the battlefield than dog tags. The Navy may have just been following suit, although the same year the Navy adopted fingerprinting, 1907, it also implemented a major change to Navy recruitment, restricting it to U.S. citizens only. Prior to 1907, any alien could join the Navy merely by stating an intention to eventually become a U.S. citizen, and a number of aliens reportedly enlisted in the Navy “just to obtain passage from one part of the world to the other.” U.S. Navy ships were often staffed by crew who spoke French, German, Spanish, Italian, Gaelic, and Chinese. In the early 1890s there was a U.S. Navy gunboat operating in Chinese waters with only one American in a crew of 135, prompting a visiting officer on one occasion to ask, “If there is anyone in the gangway who can speak English, lay aft.” [19] Thus, it may have been in connection with the new citizenship requirement that the Navy started fingerprinting and hired Mary Holland as an instructor.

Other students of Ferrier who had trained within him in St. Louis also evangelized the method throughout the U.S. law enforcement community. Fingerprinting came to the attention of the National Chiefs of Police Union, which had been formed in 1896 and is today known as the International Association of the Chiefs of Police.[20] As other forms of identification such as handwriting analysis began to fall into disrepute (including during the notorious Dreyfus affair in France, in which Alphonse Bertillon and several other experts came to contradictory conclusions about the authenticity of a particular document),[21] the National Chiefs of Police Union created a National Bureau of Criminal Identification (NBCI). It initially collected photographs and Bertillon records, with the Pinkerton Detective Agency generously donating its own collection of photographs. After it acquired fingerprints the NBCI became vastly more effective, and the entire collection was folded into the U.S. Department of Justice’s new Bureau of Investigation (BOI) upon the latter’s founding in 1908.

By then local authorities throughout the United States, not just police departments, were beginning to use fingerprinting for a variety of purposes, such as the New York City Civil Service Commission, which in 1902 began fingerprinting applicants for police and fire department jobs in order to stem the apparently widespread practice of hiring stand-ins to take civil service examinations (one man who apparently had taken exams for 12 different candidates exposed the practice when he then sued several of his clients for failure to pay him).[22] The technology was low-cost and easy to learn, a huge advantage over Bertillonage.

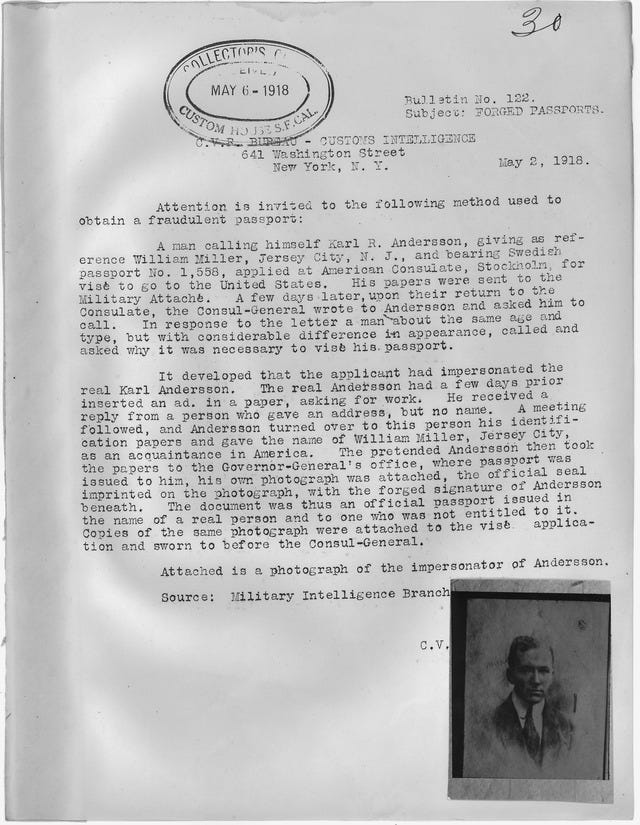

The outbreak of war on the European continent in 1914 brought with it a substantial increase in public anxiety in Britain over the possibility of German spies on British soil. In November 1914, authorities apprehended Carl Hans Lody, who had spied on Britain for Germany using a fake U.S. passport. Lawmakers responded with the Nationality and Status of Aliens Act, which for the first time required photographs and a physical description on all British passports.

“Not all were happy with official amendments. Just a fortnight after the law came into force in 1915, the explorer and natural historian Bassett Digby wrote to the Times about the Foreign Office's ‘high-handed methods’.

"’On the form provided for the purpose I described my face as “intelligent”,’ he complained. ‘Instead of finding this characterisation entered, I have received a passport on which some official, utterly unknown to me, has taken it upon himself to call my face “oval”.’"[23]

The United States had little choice but to follow suit, as Americans in Europe who now found themselves in a war zone needed identification that would satisfy European authorities while traversing the boundaries of hostile powers. On August 1, 1914, Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan sent instructions to all U.S. ambassadors and ministers in European countries, authorizing them to issue emergency passports to U.S. citizens upon request and “[d]irect all consular officers to advise American citizens within their districts to register and to give duplicate certificates of registration, with wafer seals attached, to all persons registered who do not bear passports.”[24] A month later, Acting Secretary of State Robert Lansing was compelled to issue some supplemental instructions:

“The Department is informed that many persons not American citizens apply for American passports and consular registration certificates to enable them to leave their native lands, or other European countries, and come to this country, some of them for the special purpose of evading military service. It is, therefore, especially important to observe standing instructions concerning the issuance of these documents. Regular emergency passports and consular registration certificates should be issued only to native and naturalized American citizens and citizens of the insular possessions. Native citizens can not be required to produce birth certificates, but should be required to submit satisfactory identification.”[25]

By December 1914, there were even more specific instructions:

“NATIVE AMERICAN CITIZENS

In taking the passport application of a person alleging native citizenship, you should require the applicant to submit a birth certificate, if possible, or letters or other documents satisfactorily establishing his citizenship. The nature of the evidence submitted to you must be stated in the passport application.

NATURALIZED AMERICAN CITIZENS

A person claiming citizenship by naturalization must be required to submit his certificate of naturalization or a certified copy of the court record thereof, or an old passport issued by the Department, and his passport application must state the name of the court in which he obtained naturalization and the date thereof. If any such person is unable to submit such documentary evidence of his naturalization, you should inform the Department of the name of the court in which he alleges that he obtained naturalization and the date thereof, so that the Department may take steps to verify his allegation.

PHOTOGRAPHS OF APPLICANTS

Each applicant for a passport must submit triplicate unmounted photographs of himself on thin paper, not larger than three by three inches in size, one to be attached to each of his applications by the officer before whom they are executed, and the third to be attached to the passport and to be partly stamped with an impression of the seal of the issuing office.

An application forwarded to the Department for a regular passport must necessarily be accompanied by a loose photograph of the applicant in addition to the one attached to the application, so that the former may be attached to the passport, with an impression of the Department’s seal.”[26]

By December 1915, the State Department had added the photograph requirement to issuance of passports in the United States as well, following Executive Order 2285 issued by President Wilson providing that “[a]ll persons leaving the United States for foreign countries should be provided with passports of the Governments of which they are citizens.”[27] The incredibly valuable cache of personally identifiable information in State Department files serves as a boon today for genealogists seeking photos of their ancestors.[28]

During the three years of U.S. neutrality, U.S. authorities also had to deal with a flood of European-born Canadian residents, and in the process appear to have learned quite a bit from their northern neighbors about how to register, surveill and control the movement of “enemy aliens.” In the months following the outbreak of the war, Europeans in Canada were trying to swiftly get out of Canada for a variety of reasons and were desperate to get into the United States, either to make their way ultimately to Europe or simply stay and seek work opportunities in a less hostile and neutral country. Canadians of Anglo descent expressed their loyalty to the Crown in xenophobic ways; in Toronto, an angry mob forced a random group of immigrants on the street to kneel and kiss the Union Jack.[29]

On August 14, 1914, the Privy Council issued a proclamation, P.C. 2150, granting the militia and police the authority to arrest and detail “enemy aliens.”[30] Any non-naturalized Canadian resident born either in Germany or the Austro-Hungarian Empire became classified as an “enemy alien,” who needed to be prevented from leaving Canada to join their respective countries’ militaries. This determination ignored the fact that many subjects of the latter were disenfranchised ethnic minorities (Slovakians, Romanians, etc.) who had left Europe for a reason and had no inclination whatsoever to go back and serve in the Austro-Hungarian military.

There were indeed contingents of German and (mostly) Austrian military reservists in Canada who were now heeding the call to come home and serve in their respective militaries. On August 22, 1914, the Canadian parliament enacted the War Measures Act, based largely on Britain’s Defense of the Realm Act (DORA), granting the Privy Council the power to enact, without parliamentary approval, “whatever rules and regulations were deemed necessary to maintain security, defence, peace, order, and welfare as long as the conditions of war pertained, whether real or perceived.”[31] The Canadian government leveraged its militia, the dominion police in eastern Canada, and the Royal North West Mounted Police (the Mounties) in western Canada to keep a close eye on the railways leading into the United States and prevent any German or Austro-Hungarian military reservists from leaving; they also provided regular intelligence reports to Ottawa on general immigrant “sentiment.”[32]

British and Canadian authorities might have preferred that U.S. authorities additionally prevent such individuals from entering the United States; however, they simultaneously wished to facilitate the return of British, French and Belgian military reservists who wished to serve in their respective militaries. As a neutral country, the United States did not prohibit such movement by reservists of any belligerent country unless their transit through the United States amounted to “the beginning or setting on foot or providing or preparing the means for any military expedition or enterprise to be carried on from the territory or jurisdiction of the United States”[33] (this is exactly what the members of the Ghadar Party were doing and why U.S. immigration authorities were collaborating closely with Canadian authorities in that instance, as I discussed in this post:

…and later in this post, regarding the workings of the Berlin India Committee):

Correspondence from the fall of 1914 between the pro-British Acting Secretary of State Robert Lansing (who was stepping in for Secretary Bryan during part of this time period) and various diplomatic representatives of both the Entente and the Central Powers suggest that Lansing and the British had figured out between themselves a clever means to facilitate the free movement of Entente military reservists through the “neutral” United States onward to Europe, while effectively stopping German and Austro-Hungarians from doing the same. They did so by manipulating the provision in the U.S. Immigration Act of 1894 that excluding from entry anyone “likely to become a public charge.”

On August 14, 1914, the French Chargé d’Affaires in Manchester, Massachusetts, complained to the Secretary of State that U.S. immigration officials in Montreal were not allowing letting French reservists enter the United States in order to return to France by ship out of New York.[34] The Russian, Belgian and British ambassadors to the United States soon followed suit with their own requests to facilitate the return of their nationals in Canada to Europe, via New York.[35]

On October 3, Acting Secretary of State Lansing responded with a generous and facially neutral offer to all Diplomatic Representatives of Belligerent States:

“The Department of State and the Department of Labor, after consideration of the subject, have reached the conclusion that embarrassment and criticism would be obviated by the issuance of general instructions to the United States immigration officials to permit the transit of reservists of belligerent nationalities who desire to take ship for their countries at ports in the United States, rather than to require each case to be presented separately through diplomatic channels. But, as this course will involve further relaxation of the administration of the immigration laws of the United States, its adoption will depend on the willingness of each of the Governments concerned to give to the Government of the United States an assurance that its male citizens or subjects of military age whenever permitted to enter the United States during the present war will not be allowed to become public charges in this country.”[36]

The French and British Ambassadors to the United States, as if on cue, immediately responded with assurances that they would take “necessary measures” to ensure their citizens would never become a public charge in the United States.[37] The British Ambassador, Cecil Spring Rice, noted that “so far as British reservists are concerned, any who may enter the United States from Canada en route to the United Kingdom will be permitted to return to Canada without difficulty if they should become public charges in this country, regardless of whether or not they have acquired Canadian domicile by three years residence in Canada.”[38] The Austro-Hungarian Ambassador, however, responded that “this permission will hardly concern Austrian and Hungarian citizens, as Austrian and Hungarian reservists are practically debarred from the possibility to reach the Monarchy…[t]o facilitate their passage to the United States would practically mean to increase the number of unemployed in this country liable to become a public burden.”[39]

The German Ambassador also responded that the offer would do German reservists no good, “as Great Britain has withdrawn its promise not to take persons liable to military service off neutral vessels.”[40] Military reservists were henceforth able to make their way to fight on behalf of Britain and France via transit through the United States without any hindrance from U.S. immigration officials.

The reality was that German and Austro-Hungarian residents of Canada were well on their way to becoming public charges in Canada, where they had been dismissed from their jobs in large numbers, denied the ability to become naturalized Canadian citizens for the duration of the war, prohibited from possessing firearms (which some of them needed for work), and prevented from entering into contracts (such as with mortgage companies).[41] In Montreal alone, home to approximately 8,000 Austro-Hungarian nationals, a thousand or more were out of work within a few weeks of the outbreak of the war in Europe, rendering starvation a very real possibility.[42]

“In Hull, Quebec, municipal authorities were appalled after a health inspection of overcrowded rooming houses in which Ukrainians, Poles, and other Austro-Hungarian nationals resided. There they found 125 individuals huddled together in filthy squalor, with entire families living in rooms ‘no bigger than clothes closets.’ Eighteen individuals, including women and children, were crammed into one small house described as a sty.”[43]

In desperation, German and Austro-Hungarian laborers in Canada began trying to smuggle themselves across the border.

“Mike Kitt, attempting to make the border crossing in order to look for work in the Dakotas, was arrested at North Portal, Saskatchewan, for stealing a ride on a freight train. Brought before Justice W.A. Neal, Kitt explained that without work and facing starvation he had no choice but to go to the US. The argument persuaded the judge to sentence Kitt to fifteen days of hard labour for violation of the Railway Act rather than internment.'' John Spodarulek was similarly arrested at Brockville, Ontario, when he attempted to steal across the international line. He confessed going to Hammond, Indiana, only because there was no work in Ottawa where he had been a teamster at a box factory for two years.”[44]

As the general level of anxiety and disorder increased within these immigrant communities, the Canadian public only became more concerned that they constituted a threat. Accordingly, the Privy Council’s Order-in-Council 2721, issued October 28, 1914, the Alien Enemy Registration Ordinance, now created a system of Registrars of Alien Enemies, in cities and towns designated by the Justice Minister based on the presence of alien enemies. Every enemy alien became obligated to promptly “attend before the registrar or one of the registrars, for the city, town or place within or near which he is or resides and truly answer such questions with regard to his nationality, age, residence, occupation, family, intention or desire to leave Canada, destination, liability and intention as to military service, and otherwise, as may be lawfully put to him by the registrar.” The registrar was obligated to enter this information into a book along with “such other particulars necessary for identification of such alien of enemy nationality or otherwise as may seem advisable.” Enemy aliens needed to comply with all of these provisions, carry a Canada Registration Board card with them at all times, and report in monthly to the local chief of police or else face internment as prisoners of war. [45] A total of about 80,000 Canadian residents were registered pursuant to this procedure during the war, with about 8,000 detained as POWs.[46]

How the United States eventually came to enter the war on the side of Britain was discussed in my previous post:

Once it did, it quickly implemented a system of alien registration that was remarkably like Canada’s. First, it was initiated virtually simultaneously with the declaration of war being approved by Congress. On April 6,1917, President Wilson issued Proclamation 1364, containing twelve Regulations to be applied to “all natives, citizens, denizens, or subjects of Germany, being males of the age of fourteen years and upwards, who shall be within the United States and not actually naturalized, who for the purpose of this proclamation and under such sections of the Revised Statutes are termed alien enemies.” These Regulations removed the right of enemy aliens to bear firearms or any other instruments of war, to possess ciphers or signalling devices, to “write, print, or publish any attack or threats against the Government or Congress of the United States, or either branch thereof,” or to enter or depart from the United States without authorization. Regulation 11 provided that, “If necessary to prevent violation of the regulations, all alien enemies will be obliged to register,” and Regulation 12 read as follows:

“An alien enemy whom there may be reasonable cause to believe to be aiding or about to aid the enemy, or who may be at large to the danger of the public peace or safety, or who violates or attempts to violate, or of whom there is reasonable ground to believe that he is about to violate, any regulation duly promulgated by the President, or any criminal law of the United States, or of the States or Territories thereof, will be subject to summary arrest by the United States Marshal, or his deputy, or such other officer as the President shall designate, and to confinement in such penitentiary, prison, jail, military camp, or other place of detention as may be directed by the President.”[47]

The U.S. War Department established war prison barracks at Fort Oglethorpe and Fort McPherson, Georgia, and Fort Douglas, Utah,[48] just as the Canadian authorities had revamped Fort Henry and various military camps for this purpose.[49]

Second, alien registration was carried out in a decentralized and inconsistent manner—probably even more inconsistently than in Canada, since in the United States law enforcement authority and manpower was still quite scarce at the federal level (we will get into enforcement capacity in a future post). In November 1917, President Wilson issued Regulation 19, providing for alien enemy registration, which required completion of a four-page form that included family information, details of immigration, a physical description, a photograph, and, of course, fingerprints. Throughout the course of the war, approximately 480,000 German enemy aliens were registered, with 6,300 enemy aliens arrested under Presidential Arrest Warrants. However, very few federal records exist today regarding enemy alien registration, and those that survive are incomplete and spread between records of U.S. Attorneys and Marshals, federal district courts, the U.S. Postal Service, and the Immigration and Naturalization Service.

In addition, the U.S. National Archives notes that “enemy alien registration records have been identified at a variety of locations outside the National Archives, including state archives, historical societies, and county libraries. To date, the only states with known surviving enemy alien registration records are: Arizona, Arkansas, California, Idaho, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Minnesota (state registration), New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Oregon, Texas, and Wisconsin.”[50]

What the U.S. Justice Department could offer was legal guidance and logistical support for registration and internment. On April 16, 1918, the U.S. Congress amended Section 4087 of the Revised Statutes to include an alien registration requirement for women. One of the surviving instruction manuals that the Attorney General subsequently issued to state, local and federal authorities serving as registrars provides a glimpse into how alien registration operated in practice. It also underscores how widespread fingerprinting technology had become by that time, noting helpfully that “[a]lmost all police departments are equipped with finger-print apparatus. If not, any local printer can provide the necessary printer’s ink and roller. Registration officers in nonurban areas if unable to borrow the apparatus from any police department may use the post-marking or stamp-cancelling pad.”[51]

At the same time, the Justice Department could dictate some standardization of fingerprinting in the interests of greater accuracy, probably because its Bureau of Investigation had inherited a massive fingerprint collection when it absorbed the National Bureau of Criminal Identification in 1908 and was continuing to advance the science. The Attorney General’s guidebook provided that each finger was to be fingerprinted individually, plus “plain impressions of the four fingers taken simultaneously” from both the left and right hands.[52]

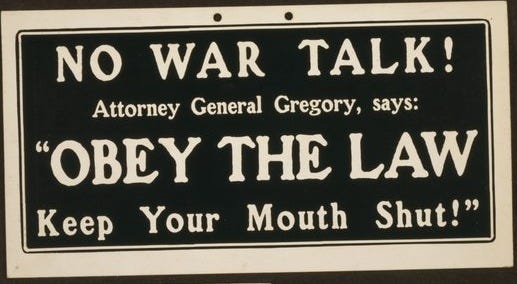

Who was in charge of all this standardization and file-keeping? With the U.S. entry into the war, Attorney General Gregory had chosen Special Assistant Attorney-General John Lord O’Brian as head of the new War Emergency Division, charged with enforcing the Espionage Act.

O’Brian hired a crack team of assistants, including a promising young law graduate named John Edgar Hoover, then working at the Library of Congress and super-excited about filing systems. Impressed with his diligence, O’Brian soon put him in charge of the Division’s new Enemy Alien Bureau. With so many of his cohort off fighting in the trenches in France, Hoover advanced quickly through the civil service hierarchy. Of hiring Hoover, O’Brian would later say, “It is one of the sins for which I have to atone.”[53]

[1] Sir William J. Herschel, Bart., The Origin of Finger-Printing (Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, 1916), at 7-8, available at https://archive.org/details/originoffingerpr00hersrich/mode/2up (viewed March 2, 2025).

[2] Sir William J. Herschel, Bart., The Origin of Finger-Printing (Humphrey Milford, Oxford University Press, 1916), at 35-37.

[3] See discussion in Daniel Asen, “Knowing Individuals: Fingerprinting, Policing, and the Limits of Professionalization in 1920s Beijing,” Modern China 2020, Vol. 86(2), 161-192, at 184 note 2 (citing to ZHAO XIANGXIN 趙向欣 _(1997) 中華指紋學 _(Chinese fingerprinting). Beijing: Qunzhong chubanshe; and Niida Noboru (1939), “A study of simplified seal-marks and finger-seals in Chinese documents,” Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko 11: 79-131).

[4] Mira Rai Waits (2016) “The Indexical Trace: A Visual Interpretation of the History of Fingerprinting in Colonial India,” Visual Culture in Britain, 17:1, 18-46, DOI: 10.1080/14714787.2016.1147978, at 27, 36.

[5] Mira Rai Waits (2016) “The Indexical Trace: A Visual Interpretation of the History of Fingerprinting in Colonial India,” Visual Culture in Britain, 17:1, 18-46, DOI: 10.1080/14714787.2016.1147978, at 21, 30.

[6] Mira Rai Waits (2016) “The Indexical Trace: A Visual Interpretation of the History of Fingerprinting in Colonial India,” Visual Culture in Britain, 17:1, 18-46, DOI: 10.1080/14714787.2016.1147978, at 23.

[7] Mira Rai Waits (2016) “The Indexical Trace: A Visual Interpretation of the History of Fingerprinting in Colonial India,” Visual Culture in Britain, 17:1, 18-46, DOI: 10.1080/14714787.2016.1147978, at 36.

[8] G.S. Sodhi and Jasjeet Kaur, “The Forgotten Indian Pioneers of Fingerprint Science: Fallout of Colonialism,” Indian Journal of History of Science, 53.4 (2018), 184-190 DOI: 10.16943/ijhs/2018/v53i4/49543, at T188-90.

[9] Mira Rai Waits (2016) “The Indexical Trace: A Visual Interpretation of the History of Fingerprinting in Colonial India,” Visual Culture in Britain, 17:1, 18-46, DOI: 10.1080/14714787.2016.1147978, at 41.

[10] G.S. Sodhi and Jasjeet Kaur, “The Forgotten Indian Pioneers of Fingerprint Science: Fallout of Colonialism,” Indian Journal of History of Science, 53.4 (2018), 184-190 DOI: 10.16943/ijhs/2018/v53i4/49543, at T185.

[11] Alison Bashford and Catie Gilchrist, “The Colonial History of the 1905 Aliens Act,” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, Vol. 40 No. 3 (September 2012), pp. 409-437, at 409.

[12] Charles Archibald Price, The Great White Walls are Built: Restrictive Immigration to North America and Australasia 1836-1888 (Canberra : Australian Institute of International Affairs in association with Australian National University Press, 1971), at 99 et seq., available at https://archive.org/details/greatwhitewallsa0000pric/mode/2up (viewed March 5, 2025).

[13] Id. at 134-35.

[14] Alison Bashford and Catie Gilchrist, “The Colonial History of the 1905 Aliens Act,” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, Vol. 40 No. 3 (September 2012), pp. 409-437, at 412.

[15] Alison Bashford and Jane McAdam, “The Right to Asylum: Britain’s 1905 Aliens Act and the Evolution of Refugee Law,” Law and History Review, 2014: 32(2): 309-350, at 314-315. Doi:10.1017/50738248014000029

[16] Alison Bashford and Catie Gilchrist, “The Colonial History of the 1905 Aliens Act,” The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, Vol. 40 No. 3 (September 2012), pp. 409-437, at 415.

[17] Alison Bashford and Jane McAdam, “The Right to Asylum: Britain’s 1905 Aliens Act and the Evolution of Refugee Law,” Law and History Review, 2014: 32(2): 309-350, at 319.

[18] Russell R. Bradford, “America’s First Fingerprint Instructor,” The Print, Vol. 14(5), September/October 1998, pp. 1-2, available at https://web.archive.org/web/20170122215412/http://www.scafo.org/library/140501.html (viewed March 6, 2025); Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Harvard University Press, 2001), at 138.

[19] Chief Journalist O.S. Roloff, U.S. Navy, “One Hundred and Eighty Years of Naval Recruiting,” United States Naval Institute Proceedings, December 1956, Vol. 82/12/646, available at https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1956/december/one-hundred-and-eighty-years-naval-recruiting (viewed March 6, 2025).

[20] “Milestones in the History of the Profession,” National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund, available at ??

[21] Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Harvard University Press, 2001), at 200.

[22] Simon A. Cole, Suspect Identities: A History of Fingerprinting and Criminal Identification (Harvard University Press, 2001), at 135-36.

[23] Justin Parkinson, “How Have Passport Photos Changed in 100 Years?,” BBC News Magazine, February 5, 2015, available at https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-30988833 (viewed March 6, 2025).

[24] The Secretary of State to the Ambassadors and Ministers in European Countries, Department of State, Washington, August 1, 1914, File No. 300.11/8a, Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1914, Supplement, the World War, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1914Supp/d1145 (viewed March 6, 2025). This order by Bryan was apparently followed by President Woodrow Wilson’s Executive Order 2021 of August 14, 1914, Amending the Rules Governing the Granting of Passports; see https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/executive-order-2021-amending-the-rules-governing-the-granting-passports (viewed March 6, 2025).

[25] The Secretary of State to the Ambassadors and Ministers in European Countries, Department of State, Washington, September 12, 1914, File No. 138.4/27a, Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1914, Supplement, the World War, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1914Supp/d1148 (viewed March 6, 2025).

[26] William Jennings Bryan, The Secretary of State to the Ambassadors and Ministers in European Countries, Department of State, Washington, December 21, 1914, File No. 138/48a, Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1914, Supplement, the World War, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1914Supp/d1152 (viewed March 6, 2025).

[27] Executive Order of December 15, 1915, reprinted in Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1914, Supplement, the World War, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1915Supp/d1288 (viewed March 7, 2025).

[28] See U.S. National Archives, “Research our Records: Passport Applications,” at https://www.archives.gov/research/passport (viewed March 7, 2025).

[29] Bohdan S. Kordan, No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2016), at 30.

[30] Mary Chaktsiris, “Identifying the Enemy in First World War Canada: The Historiography and Bureaucracy of Enemy Alien Internment and Registration,” Canadian Military History, Vol. 28, Issue 2 (2019), at 17, available at https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh/vol28/iss2/19/ (viewed March 7, 2025).

[31] Bohdan S. Kordan, No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2016), at 39; Mary Chaktsiris, “Identifying the Enemy in First World War Canada: The Historiography and Bureaucracy of Enemy Alien Internment and Registration,” Canadian Military History, Vol. 28, Issue 2 (2019), at 17.

[32] Bohdan S. Kordan, No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2016), at 17-18.

[33] Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, The Secretary of State to the Consul General at Vancouver (Mansfield), Telegram from Washington, August 13, 1914, Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1914, Supplement, the World War, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1914Supp/d899 (viewed March 7, 2025) (emphasis added).

[34] French Chargé d’Affaires (Clausse) to the Secretary of State, French Embassy, Manchester, Massachusetts, August 14, 1914 (received August 17), File No. 150.07/17, Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1914, Supplement, the World War, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1914Supp/d900 (viewed March 7, 2025). Only one day prior, Secretary of State Bryan had informed the U.S. Consul General in Vancouver, in response to his inquiry, that U.S. immigration officials (who fell under the Labor Department at that time) could allow French reservists to enter the U.S. from Canada as long as they were not launching a military expedition from U.S. soil. Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, The Secretary of State to the Consul General at Vancouver (Mansfield), Telegram from Washington, August 13, 1914, Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1914, Supplement, the World War, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1914Supp/d899 (viewed March 7, 2025).

[35] The Secretary of State to the Belgian Minister (Havenith), Department of State, Washington, August 18, 1914, File No. 150.07/45a; The Russian Ambassador (Bakhméteff) to the Secretary of State, Russian Embassy, Newport, Rhode Island, August 27, 1914, File No. 150.07/21; The Secretary of State to the Russian Ambassador (Bakhméteff), Department of State, Washington, August 28, 1914; the Secretary of State to the French Ambassador (Jusserand), Department of State, Washington, September 4, 1914, File No. 150.07/17; the Acting Secretary of State [Lansing] to the Belgian Minister (Havenith), Department of State, Washington, September 18, 1914, File No. 150.07/61b; the British Ambassador to the United States (Spring Rice) to the Secretary of State, British Embassy, Washington, September 25, 1914, File No. 150.07/37; all available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1914Supp/ch24 (viewed March 7, 2025).

[36] The Acting Secretary of State to the Diplomatic Representatives of Belligerent States, Department of State, Washington, October 3, 1914, File No. 150.07/47b, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1914Supp/d907 (viewed March 7, 2025) (emphasis added).

[37] The French Ambassador (Jusserand) to the Secretary of State, French Embassy, Washington, October 10, 1914, File No. 150.07/47, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1914Supp/d908 (viewed March 7, 2025).

[38] The British Ambassador (Spring Rice) to the Secretary of State, British Embassy, Washington, October 27, 1914, File No. 150.07/50, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1914Supp/d910 (viewed March 7, 2025).

[39] The Austro-Hungarian Ambassador (Dumba) to the Secretary of State, Austro-Hungarian Embassy, Manchester, Massachusetts, October 12, 1914, File No. 150.07/46, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1914Supp/d909 (viewed March 7, 2025)(emphasis added).

[40] The German Ambassador (Bernstorff) to the Secretary of State, German Embassy, Washington, November 17, 1914, File No. 150.07/56, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1914Supp/d911 (viewed March 7, 2025).

[41] Bohdan S. Kordan, No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2016), at 36-44.

[42] Bohdan S. Kordan, No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2016), at 64-65.

[43] Bohdan S. Kordan, No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2016), at 71.

[44] Bohdan S. Kordan, No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2016), at 68.

[45] Alien Enemy Registration Ordinance, P.A.C., RG2, 1, v.1324. PC 2721 of 28 October 1914, available at https://web.viu.ca/davies/H355.Cda.%20at%20War/AlienEnemyRegistrationAct.1914.htm (viewed March 7, 2025). An image of a Canadian Registration Board card on a Ukrainian resident of Canada can be seen at “Ukrainian Canadian Internment Archival Documents: Wasyl Severyn Family Story,” Ukrainian Canadian Civil Liberties Association, available at https://www.uccla.ca/internment-archival-documents (viewed March 7, 2025).

[46] Mary Chaktsiris, “Identifying the Enemy in First World War Canada: The Historiography and Bureaucracy of Enemy Alien Internment and Registration,” Canadian Military History, Vol. 28, Issue 2 (2019), at 27, available at https://scholars.wlu.ca/cmh/vol28/iss2/19/ (viewed March 7, 2025).

[47] “April 6, 1917: Proclamation 1364 Transcript,” Presidential Speeches, Woodrow Wilson Presidency, reproduced at University of Virginia Miller Center, available at https://millercenter.org/the-presidency/presidential-speeches/april-6-1917-proclamation-1364 (viewed March 8, 2025).

[48] “World War I Enemy Alien Records,” U.S. National Archives, available at https://www.archives.gov/research/immigration/enemy-aliens/ww1 (viewed March 7, 2025).

[49] Bohdan S. Kordan, No Free Man: Canada, the Great War, and the Enemy Alien Experience (McGill-Queen’s Press, 2016), at 104-05.

[50] “World War I Enemy Alien Records,” U.S. National Archives, available at https://www.archives.gov/research/immigration/enemy-aliens/ww1 (viewed March 7, 2025).

[51] U.S. Department of Justice, Registration of German Alien Females, General Rules and Regulations, Prescribed by the Attorney General of the United States Under the Authority of the Proclamation of the President of the United States, dated April 19, 1918, p. 17.

[52] U.S. Department of Justice, Registration of German Alien Females, General Rules and Regulations, Prescribed by the Attorney General of the United States Under the Authority of the Proclamation of the President of the United States, dated April 19, 1918, p. 14 (sample registration form).

[53] Roger K. Newman, ed., The Yale Biographical Dictionary of American Law (Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT), at 405.