I should note at the outset that, after all these years, we still don’t know whose idea it was to blow up Frank Sakamaki’s house on June 3, 1920, or why he in particular was targeted. We don’t know this, despite a monthlong trial against 21 defendants, whose transcript has been exhaustively studied in recent years by Umewaza and Peter Duus.[1] We do know who physically carried out the attack: Junji Matsumoto, Kaichi Miyamura, and a 27-year-old named Saito, who was working as a cement mixer on a military base after being evicted by the plantation owners during the strike. Matsumoto would later become a star prosecution witness, Miyamura would escape to Japan, and as for Saito, even his first name has been lost to history.

So let’s start with what we know about the Great Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920. In Part One,

I explained how this particular historical episode ties into my larger work, which explores whether and to what extent the fateful decision by the United States in 1898 to acquire a European-style colonial island empire is at the root of intractable modern debates over warrantless Internet surveillance by the NSA.

Experts on the history of the U.S. intelligence community would most likely agree that the single most important historical event that finally prompted the United States to create a permanent, peacetime intelligence-gathering capacity—with an emphasis on communications intercepts or SIGINT—was the December 7, 1941 Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor.

But what led to that attack to begin with? In an age in which Japan was actually building a naval alliance with Great Britain, and the Western powers welcomed Japan’s efforts to check Russian ambitions, what was it that set this emerging Pacific naval power on a collision course with the other emerging Pacific naval power, the United States? Was this clash inevitable given the competition between them for access to China, or did certain things happen at the end of World War I that destroyed what could have been a relationship of mutual understanding and respect? And how did it all come to its epochal inflection point at Pearl Harbor (which I’m going to continue to put in bold font wherever it appears)?

Rice riots, the strikes of 1919, and the rising cost of groceries

Where we left off in Part One, the sugar plantation owners, acting through the HSPA, were by 1919 still scouring the earth for any variant of the species homo sapiens who might genuinely enjoy working 10-hour days harvesting sugar cane in the hot equatorial sun with overseers on horseback whipping them (there’s video at that link from 1902, complete with overseer on horseback!), and they were coming up short. By this point, the ethnicities and nationalities represented on the sugar plantations included Chinese, Japanese, Polynesians, Portuguese, Germans, Norwegians, Spanish, Australians, Italians, Puerto Ricans, African Americans, Koreans, Filipinos, and Russians.[2] The HSPA had also brought in some Scottish former ship hands as overseers who were known to be particularly merciless with the whips.[3]

The armistice reached between Germany and the Allies on November 11, 1918, had not necessarily brought much peace to Japan, which, having been caught by surprise by an Anglo-American intervention into Siberia in late 1917, quickly sent its own land forces there to oppose the Red Army. A total of 70,000 Japanese troops eventually occupied several cities in Siberia, along with 50,000 civilian settlers, and did not withdraw until 1925.[4] The need to stockpile rice for all these troops was a large factor in the precipitous rise in the price of rice, leading to the 1918 “rice riots” in Japan and also causing huge price increases in Hawai’i, where 48 percent of Hawai’i’s population was now ethnically Japanese[5] and a daily consumer of imported Japanese rice.

The cost of imports from the U.S. mainland was also increasing. Between 1917 and 1920, the Consumer Price Index had risen more than 40 percent, with food prices over 50 percent.[6] Then, in early 1919, the strikes began: first, Seattle on February 6, in which 35,000 shipyard employees walked off the job and then 25,000 from others joined them, freezing all public transportation and closing the public schools. The strike only lasted four days, but the solidarity and coordination among the strikers inspired others.[7] Over the course of the rest of the year, a total of four million people, one out of every five workers, went on strike: “telephone operators in New England, blacksmiths in Ohio, streetcar drivers in Indiana, cigar makers in Baltimore…In Portland, Oregon, and Tacoma, Washington, socialists, radical labor unionists, and discharged soldiers borrowed a word from the Russians and formed groups they called soviets.”[8]

Hawai’i followed suit, with eight small-scale strikes in 1919: longshoremen, telephone operators, machinists, lumber workers, and golf caddies. The Japanese language newspapers, led by Noboru Tsutsumi, began reporting on the need for the cane field workers to have a wage increase as well. The press coverage that year was somewhat overshadowed by two other major events: the centennial of the death of King Kamehameha, and the opening of the U.S. Navy’s dry dock at Pearl Harbor.[9]

Summer of 1919: Manlapit and Tsutsumi take charge

In the meantime, however, the 13,000, multilingual but less literate Filipino sugar cane workers were beginning to coalesce into a movement under the leadership of Pablo Manlapit.

Manlapit, who had been hired by the planters in 1916 to “take charge of relations with the Filipinos,” had been shortly thereafter implicated in a scheme by another planters’ association official named Snyder, who was recruiting laborers to go to the mainland. He thereafter became increasingly known among Filipinos as someone who simply helped out Filipinos.[10] He worked as an interpreter for the Honolulu police, the courts and local law firms, and in June 1919 he briefly obtained a court order granting himself admission to practice law in Honolulu despite lacking any formal education, an order that was then rescinded following objections by another attorney who claimed this would lower the standards of the local bar, and also bringing up the 1916 scheme involving Snyder.[11] On August 31, 1919, a thousand Filipino workers rallied at Alaa Park in Honolulu and elected Manlapit the president of their labor union, calling for higher wages and shorter work hours for the sugar cane workers.[12] By November 1919 Manlapit was organizing on the Big Island as well, touring plantations and holding sizeable rallies at the Gaiety Theater for Filipino workers in Hilo where the Hilo Daily Tribune described him as having “all the mannerisms of radical labor leaders, with enthusiasm to spare.”[13]

Manlapit’s steadfast compatriot, as he toured the Big Island that November, was Noboru Tsutsumi, who only a month earlier had organized the Federation of Japanese Labor on Hawaii, the only island to organize thus far.[14]

Tsutsumi, a more highly educated man even than most of the local newspaper writers, had by this point decided that he simply was a sugar field laborer, delivering speeches in plain words that electrified the workers:

To live in society as a human being. These times compel me to realize that I am a laborer. The sunlight of democracy shines and labor groups are blossoming. I'm the same as other human beings, so I would like to pluck the beautiful flowers of real society. . . .

If the company cannot survive because the price of sugar is low, we could understand the need to help each other and would put up with eating rice gruel. But at a time when the price of sugar is going from $60 a ton to $80, then to $100, to $150, and to more than $200, our bosses are full of idle talk that they are flush, have money left over, are getting large dividends; and they're lording it over us by living in grand houses and riding around in big cars….

Laborers threatened by economic distress are forced to consider their present circumstances and the future of their descendants. The single word pau [finished; fired] ruins the foothold gained over several decades, forcing a household to keep from uttering it. The bosses are trying to oppress us by treating us as they treated government contract immigrants or ignorant laborers in the past. This is unacceptable to progressive thinking youths and laborers who are in touch with current trends. And yet, in the struggle between employer and employee, we are weak as individuals.[15]

The Japanese delegation to the Versailles Conference passes through town

In Honolulu on Oahu, other elements of the large Japanese community had a wider range of interests, as the Japanese Association there consisted of upscale shop owners, newspapermen, and similar professionals, who had time to ruminate on loftier subjects, such as foreign policy. In 1919, many prominent Japanese leaders came through Honolulu on their way to or from the Versailles Peace Conference. Japan’s delegation had been sent to Paris with three goals: “to get a clause on racial equality written into the covenant of the League of Nations, to control the north Pacific islands and to keep the German concessions in Shantung. Otherwise, according to instructions, it was to go along with Wilson’s Fourteen Points.”[16] The white Western powers’ rejection of the racial equality clause (mostly due to objections from the Australian portion of the British delegation, who insisted that “No Govt. could live for a day in Australia if it tampered with a White Australia”) had particularly stung.[17]

In Honolulu, even if their ship was in port for less than a day, these Japanese dignitaries were often invited to give fiery remarks at lecture meetings sponsored by the local newspapers.

For example, Seigo Nakano, editor-in-chief of Toho jiron, declaimed that "a clash between Japan and America" over the future of Japanese interests in China would be "difficult to avoid." Calling the white man a villain and waving the rising sun flag were dangerous in a society dominated by Caucasians, but the Japanese audience greeted Nakano's speech with applause and cheers. The Japanese newspapers, reporting these events in florid language, made them the topic of the day at barber shops and public baths or at lunchtime in fields of the sugar plantations.[18]

Thankfully, from the Japanese perspective, Japan had been able to lay claim to all the tiny Pacific islands it had wanted for its burgeoning navy—Tinian, Saipan, Truk—and which it would proceed to militarize in the years to come despite promises to the contrary.[19] In October 1920, the Japanese Ambassador to London would seek an official naval aviation mission to Japan to provide flying training and advice on aviation technology and equipment and on building aircraft carriers.[20] After all, the Americans were militarizing Pearl Harbor.

(See? I’m still reading that book with the ugly book cover)

Other visiting Japanese leaders urged caution, however. Baron Shinpei Goto, who visited in November 1919, advised “the fortunate Japanese here in Hawai’i” to “adopt the standards and ideals of the American nation. They must realize that they are part and parcel of the body politic of the United States and not of the body politic of Japan."[21]

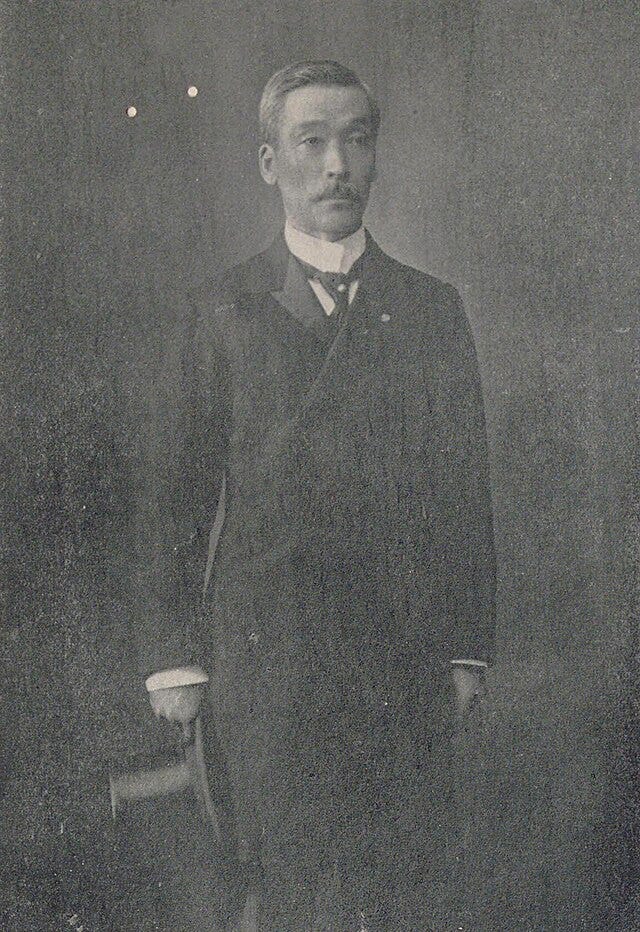

Among the many Japanese officials attempting to navigate the U.S.-Japan relationship through these treacherous waters, while looking out for the welfare of Japanese residents of Hawai’i, was Acting Consul General Eiichi Furaya, posted to the Japanese Consulate in Honolulu. The 45-year-old Furaya was not a typical career diplomat, but he had worked for a time at a customs house in Yokohama and then in Seattle, Shanghai and Liaoyang as vice consul before being posted to Honolulu under Consul General Rokoru Moroi in mid-1918, only 6 months after Tsutsumi had arrived in Hawai’i to take a position as school principal. In August 1919, Furaya was then forced into serving in the “acting” Consul General role after Moroi was recalled to Japan. Moroi’s appointed successor, Chonosuke Yada, was an experienced former consul general from New York, but by 1920 Yada was still stuck at the Foreign Ministry in Japan, his posting to Honolulu having been delayed for reasons unknown.[22]

Late 1919: Manlapit and Tsutsumi mull over a strike

Tsutsumi did not typically consort with such rarified company, instead associating himself primarily with people like Ichi Goto, a farm boy who had worked on a sugar plantation after his father brought him to Hawai’i at the age of 15. Goto had attended an English-language night school in Honolulu while working as a house boy and later became a reporter for the Nippu jiji, one of the leading Japanese newspapers in Honolulu. He resigned from his job at the newspaper in order to become secretary of the Federation of Labor under Tsutsumi’s leadership.[23]

Hiroshi Miyazawa was of a similar background, but he had become well aware of the conditions of the plantation laborers while working for a labor contractor as an interpreter. He was in charge of the Federation’s close liaison with the Filipinos in particular.[24] On the Waialua Plantation in Oahu, the laborer’s union was largely organized by Honji Fujitani, with Tokuji Baba as its titular president.[25] Fujitani sometimes hired the brawler Matsumoto for odd jobs.

On December 6, 1919, when the Japanese sugar cane labor representatives formally presented to the Hawaiian Sugar Planter’s Association (HSPA) its demand for a wage increase, the field laborers were earning 77 cents a day (58 cents for women, who comprised 14% of the workforce) and wanted $1.25 for male laborers (95 cents for women). By comparison, Seattle longshoremen were demanding $5.25 per day for unskilled laborers, and San Francisco stevedores, $8.80.[26] The HSPA, arguing that housing, lighting and fuel costs were provided by the plantations, refused to budge.[27] On December 14, the Filipino Labor Union, which had presented a set of similar demands, held a delegates’ meeting at which they voted unanimously to strike, sending a telegram to Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labor: “Deliberating strike. Hope for your utmost support.” The Japanese held back, hopeful for a lawful settlement with the HSPA based on “temperate discussion.”[28]

But Pablo Manlapit was not a temperate man. By January 14, 1920, the HSPA having rejected all demands, the Japanese federation’s leaders were having heated, all-night discussions at the Kyórakukan restaurant, which had a detached cottage with a Japanese-style bath in the back, to discuss whether to strike.

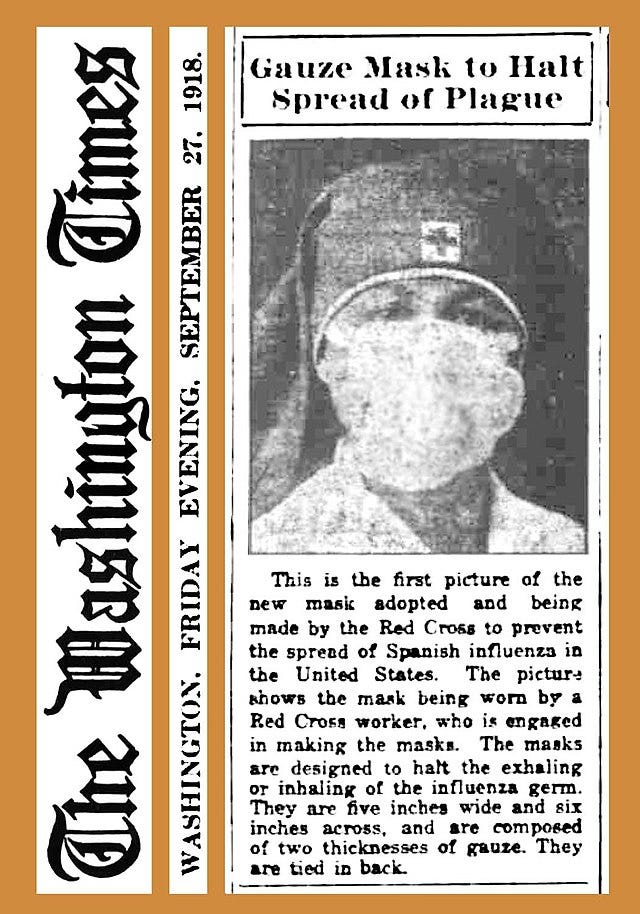

They would need to be able to cover the costs of the strikers, but the local branches of the Yokohama Specie Bank and the Pacific Bank, founded by the leading Japanese merchants with support from Eiichi Shibusawa and other Japanese industrialists, refused to lend them money. Meanwhile, the Filipinos under Manlapit had announced they would strike in two days, and this despite a local outbreak of the Spanish flu pandemic.[29]

As Manlapit scrambled to find financial support for his strikers, he quickly learned the Filipinos were in an even worse situation than the Japanese. There were no Filipino support associations on the island to support his cadre of mostly single, illiterate young men, who amused themselves by organizing cockfights and rumba dance parties, sometimes leading to homosexual activity, for which the Japanese held them in contempt.

Manlapit tried to get financial support for his strikers from the Japanese Chamber of Commerce in Honolulu and was summarily rebuffed. He announced that a strike would begin on January 17, then postponed it to January 19, then postponed it again because had hadn’t even obtained the support of the Japanese Federation of Labor.[30]

January 18, 1920: Someone just had to question someone else’s manhood, and they all had machetes

But then events spiraled even out of Manlapit’s control, thanks to a single overseer who, in his infinite wisdom, decided to question the Filipinos’ manhood. On January 18, this overseer, who was on the Kahuku Plantation and may have been a Hawai’ian native, reportedly sneered at them "No can strike, you, Filipino, hila hila [cowards]." That night, the workers at Kahuku decided to simply ignore Manlapit and start the strike. Word spread quickly to the other plantations throughout Oahu. The very next morning, Filipinos loudly and angrily walked off the job, as the startled Japanese were arriving for their shifts by train.

Tsutsumi and the rest of the Japanese Labor Federation were caught flat-footed, as the English-language press in Honolulu, ever distrustful of the Japanese amidst the outcome of the contentious Versailles Conference, announced the news under the headline “Japanese cane workers threaten general strike.” This prompted a statement from the Japanese Labor Federation that, if the Filipinos were to go on strike, "Our position and intentions are wholly legal and orderly. If a strike of Japanese labor shall be called, [the laborers are] cautioned to quit their places in a quiet and peaceable manner." As for the Japanese field workers themselves, they were disinclined to follow the lead of Filipinos, whom they looked down upon, and continued to work their shifts in the sugar fields pending further instruction.

This, in turn, enraged the Filipinos, who may not have had much wealth or personal possessions, but they did have their work-issued machetes, scythes and knives. In the pre-dawn hours of January 21, 1920, Japanese field workers stepping off the train at the Waipahu, Ewa and Aiea Plantations were suddenly accosted by armed, striking Filipinos who now regarded them as scabs.

Terrified, the Japanese workers returned to their camp houses, lunch pails in hand, while at Aiea Plantation the train engineer and plantation guard fled into the sugar fields and hid there until the sun went down.

From that point on, the Japanese Federation of Labor and the laborers themselves felt they had no option but to support the strike, not only in solidarity but for their own personal safety. The Federation quickly gathered at the Palama Japanese-language school on January 25.

At about 4:00 P.M. it went into a secret session closed to outsiders under tight security, guarded by directors carrying pistols. At 10:00 A.M. on the morning of January 26 the Federation of Japanese Labor in Hawaii resolved unanimously to "carry out a walkout by the Federation as of February 1” if there was no change in the attitude of the HSPA.

Secretary Noboru Tsutsumi, as representative of the participants, read aloud the resolution. After waiting for the applause to die down, he explained the organization of federation headquarters. He said that the three secretaries, Tsutsumi, Miyazawa, and Goto, would remain in their positions as agreed upon when the federation was established. The meeting also reconfirmed that the strike would be held only on the island of Oahu, with workers on the outer islands raising support funds. They also needed to be prepared to assist in covering the strike expenses of the Filipinos.[31]

On January 30, Manlapit and Tsutsumi spoke jointly at a rally at Waipahu, calling for unity between the Japanese and the Filipinos and an anticipated 5- to 6-month strike, to thunderous applause.[32]

February 1920: Pity the Acting Consul General

Over at the Japanese Consulate, Acting Consul General Furaya was reading with increasing concern about some of Tsutsumi’s public remarks at the subsequent series of rallies. On February 12, the Honolulu Star Advertiser reported that

Following exactly the program of the I.W.W., T. Tsutsumi, Japanese strike leader, is reported to have stated during a speech he recently made to striking workers at Waialua that “when the weeds grow up in the cane fields beyond control and the planters give up the plantations, we will go in and take possession of same and will conduct the plantations ourselves,” [later adding], “Don’t worry. A Japanese cruiser is coming to take you home. Why deny that the Japanese Government is back of the labor question? Don’t deny it. It will surely scare the Americans.”[33]

The insinuation that the Japanese government was plotting to sow mayhem in the American sugar industry could not have come at a much worse time for U.S.-Japan relations following the Versailles Conference. Unfortunately, portraying the strike as an anti-American, Japanese conspiracy was a phenomenally useful tool for the HSPA to delegitimize it; on January 31, the Star-Advertiser ran an editorial that asked, “"What is Hawaii going to do about it? What is the Government of the U.S. going to do? Is Hawaii ruled from Tokio?"[34]

Also February 1920: Manlapit leaves them at the altar after 20 days

By the time Furaya had invited Tsutsumi over to the consulate for a chat about his public remarks, the HSPA had successfully driven a wedge between the Filipino and Japanese labor movements, with a little help from public health authorities. On February 8, the Board of Health supposedly convinced Manlapit to call off the Filipino strike, because the HSPA had disclosed plans to evict all the strikers from their plantation houses, and health authorities were concerned about the mass movement of people that would result.

The flu was indeed a real threat, as the union’s representative on Maui succumbed to it that same month and was replaced by a somewhat mysterious subordinate union member named Seiichi Suzuki.[35] But Manlapit was then entrapped by the HSPA’s lawyers into admitting, in the presence of a hidden stenographer, that he would accept a $50,000 bribe to call off the strike. In the resulting uproar, only 257 Filipino laborers on Oahu followed Manlapit's order to return to work, the remainder boarding trains for Honolulu upon eviction from their camp housing, as the Japanese were now enraged that the Filipinos who had started the strike had folded after only 20 days.[36]

The Japanese labor leaders of the Federation were all too aware of the need for unity within their ranks. The Federation had issued a statement to its members back in December warning against acting like okintamamen, “a word said to be derived from a term referring to sumo wrestlers who curried favor with higher ranking wrestlers by washing their private parts. In this case, it meant those in collusion with the planters.”[37]

It also warned members that "Should a member be found guilty of the act of contravening the interest of this Federation, . . . he should be reported to several affiliated branches . . . and to the mayor of the offending member's permanent domicile in Japan."[38] This shaming tactic, which aimed at warning members that even their family members back home in Japan would bear the stain of their dishonor, was portrayed by the HSPA in the press as further evidence of Japanese government collusion with the strikers, to Acting Consul General Furaya’s great frustration.[39]

March 12, 1920: Nothing to see here, just a Japanese battle cruiser docking at Pearl Harbor

On March 12, when the Japanese cruiser Yakumo received special permission from the U.S. Navy to dock at Pearl Harbor, Furaya ensured that Japanese residents abstained from the usual welcoming reception, lest anyone believe Tsutsumi’s claims that the cruiser was there to “rescue” the strikers.[40]

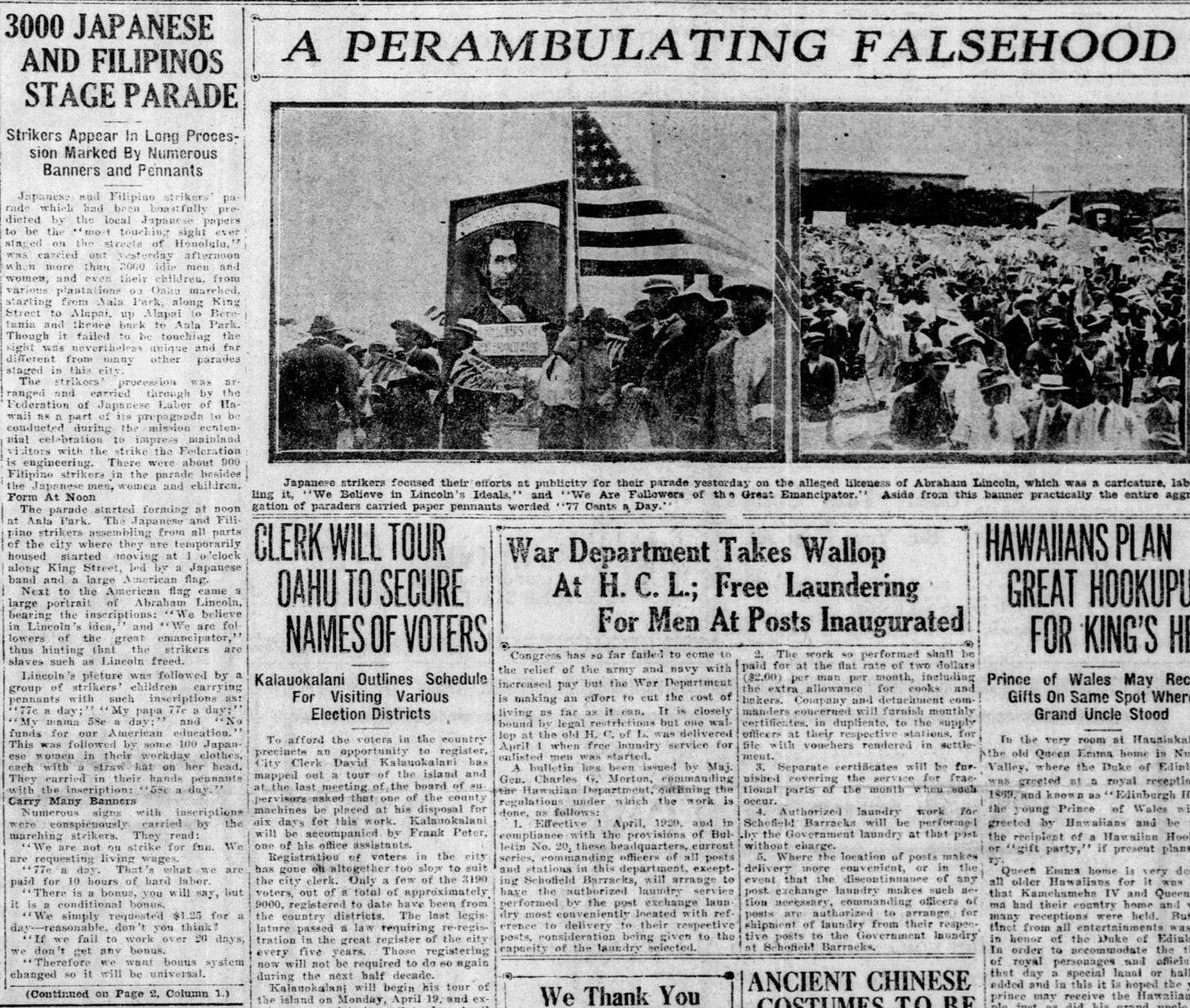

April 3, 1920: The 77-cent parade

The Federation finally responded to the HSPA’s anti-Japanese propaganda with a thoroughly American parade. On April 3, a group of more than 3000 demonstrators from 14 different plantations marched down the streets of Honolulu behind a large American flag, carrying signs including a hand-drawn picture of Abraham Lincoln over the words "Hawaii's sugar plantation workers are still suffering under slave-like treatment. Free these slaves."

Men carried small white flags reading “77 cents a day,” while womens’ flags read “58 cents a day.”

Leaflets handed out to spectators expressed the workers' grievances: "77 cents a day, that's what we are paid for 10 hours of hard labor"; "We are not Reds, God forbid, but brown workers who produce white sugar"; "We simply requested $1.25 for a day—reasonable, don't you think? We are requesting living wages";…"Can you support your family on 77 cents a day?" "We are sincerely wishing for the prosperity of Hawaii"; and "God created people to be equal."[41]

One U.S. sailor was so moved by the demonstration that, in the rally that followed in Aala Park, he asked permission to address the crowd and then, in uniform, proclaimed,

"I am a seaman and I earn $3 a day. Why is it that working under this scorching sun in Hawaii earns only 77 cents a day? It is a major embarrassment that there are such low wage earning workers in a leading civilized country like America. I think you should demand $5 a day, or even $10 a day."[42]

The Federation later that month rebranded itself as the Hawai’i Laborers Association, downplaying its Japanese ethnicity (although Pablo Manlapit was most certainly not included in the leadership of this “new” organization).

March-May 1920: Scabs, dynamite and a lot of secret meetings

In the meantime, the HSPA was already importing scab workers. Some of them were Korean or Chinese, disinclined towards unity with the Japanese, others were Filipinos newly arrived from the Philippines in March or unemployed residents of the other islands. The HSPA offered scab workers $3-3.50 per day.[43] Rumors began to spread about whether the Federation’s officials were passing along adequate financial compensation for the striking workers or spending it on themselves at local restaurants.

On May 21, Junji Matsumoto, who was still employed largely running errands for Fujitani on Waialua Plantation on Oahu, travelled with him to Federation headquarters in Honolulu to meet with Tsutsumi, Miyazawa, and Baba, who purportedly offered them a “secret job.”

The next night the two travelled onward to Hilo on the Big Island, where they met with the local union president Kaichi Miyamura and two associates. It was Miyamura, Matsumoto would later testify, who offered him $5000 to assassinate 50-year-old translator Juzaburo “Frank” Sakamaki, who worked for the Olaa Plantation. Matsumoto accepted.[44]

Because Miyamura and several others purportedly had already returned to Japan by the time Matsumoto was testifying against him in 1922, we do not have a coherent explanation for why Sakamaki in particular was singled out. Matsumoto and Sakamaki had had an altercation 6 or 7 years earlier, but of course, Matsumoto had had physical altercations almost everywhere he had ever worked, and Sakamaki would later testify that they held no grudges against one another.[45] Sakamaki also testified that his attempts to obstruct the strike on Olaa were limited to placing the newspaper Kazan (Volcano) where the laborers would see it, hardly something that would have attracted such focused attention from the Federation’s leaders.[46] .Nonetheless, it certainly is not difficult to imagine any of a number of other reasons why an anti-strike interpreter working for the Olaa plantation, who came across as arrogant and who “often treated his fellow Japanese who worked in the cane fields with a lack of generosity that bordered on the malicious,” might have gotten on someone’s bad side in this milieu.

The plan, for which Miyamura paid Matsumoto $100 in advance for “expenses,” involved Matsumoto simply escorting Miyamura and an accomplish named Saito to Sakamaki’s house on the Olaa plantation. Matsumoto testified under oath that, until the night of June 3, he had no idea that the attack would involve dynamite.[47] The dynamite had come into Miyamura’s hands via Seiichi Suzuki, the mysterious union representative from Maui who had once worked on a mountain tunnel, was therefore familiar with dynamite, and somehow acquired thirty sticks of it in April from “N. Fujii,” a guard at the Paia plantation warehouse.[48]

Suzuki reportedly discussed with Federation leaders at their Honolulu headquarters the possibility of using small amounts of the powder from these dynamite sticks to “scare the strikebreakers.”[49] He ended up giving two sticks of dynamite to the president of the Waipahu plantation union, Furusho,[50] who may have planted it under the house of a Filipino strike-breaker at Waipahu in the latter part of April.[51] Somehow, Miyazawa also acquired some of this dynamite.

June 3, 1920: The night Frank Sakamaki didn’t get very much sleep

According to Matsumoto’s testimony, on June 3,

As directed by Murakami, Matsumoto went to the Matano Hotel at 8:00 P.M. Murakami left the hotel soon thereafter to hire a car to drive to Olaa Plantation. Matsumoto waited at the corner, dressed in a suit and necktie and wearing a hunting cap, and Saito waited at a different corner. Arriving in a large model Hudson (large enough to seat seven people) with a driver hailing from Okinawa, Murakami picked up the two men to drive to Olaa. Matsumoto recalled that Sakamaki often went to evening meetings at the Japanese Church, so he had the car stop there first. Peering through a window, Matsumoto did indeed see Sakamaki, who later came out and got in his car to go home. The Hudson carrying Matsumoto and the others followed him to railroad tracks near the Sakamaki house. Murakami had the car stop just before the tracks. He got out with Saito, who was also riding in the backseat…[This appears to be when Saito and Murakami retrieved the dynamite, which took them 30 minutes before they returned to the car.]

The Hudson moved on slowly. Murakami and Saito jumped out just before Sakamaki's house and disappeared into the darkness. The car, carrying Matsumoto and the driver, drove on to Shipman Road to wait for the two men as arranged. After twenty or thirty minutes, Murakami and Saito came running breathlessly. Jumping into the backseat, they told the driver "to start the machine and go fast." The driver pushed the accelerator to the floor and sped off toward Hilo.[52]

Moments later, Frank Sakamaki was in bed upstairs when he heard a noise that he thought was a water tank falling down. His wife and young son were also awakened by the noise, and when his son said he smelled powder, Frank realized it was an explosion. He ran downstairs into such thick smoke that he could not see, somehow ran out, through the sugar cane fields, to the inspector’s house, then to the Olaa Sugar Company office to call the police, then back to his house, by which point the smoke had cleared enough for him to see that the entire side of his house had been blown off.[53]

Matsumoto had not heard any explosion as he drove off that night. The trio of accomplices returned as quickly as they were able, while evading police attention, to Honolulu, where Matsumoto proceeded to Federation headquarters and was congratulated by Tsutumi and others for having “done well” and scared all the “spies” in Hilo, despite having failed to kill Sakamaki as agreed upon.[54] Nonetheless, five or six months then went by, with no further word on when Matsumoto would receive the $5000 promised. The strike had long since ended in late June, with Acting Consul General Furaya putting pressure on the Federation to negotiate, and pressure on the HSPA coming from, of all people, Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer.

(Remember that guy? He’s towards the end of this post.)

Palmer, who had not yet experienced the political backlash that would eventually come about as a result of his early 1920 “Palmer raids,” was still harboring presidential aspirations in June and was quite taken with the rising cost of consumer staples on the U.S. mainland, particularly the price of sugar. When told that sugar production in Hawai’i might be down due to a strike, he “he fired off a telegram to Hawaii saying that any further decrease in sugar production would pose a grave problem to the entire country and urged the immediate resolution of the dispute.” The HSPA agreed to raise wages to $2.50 a day, although in the months to come the plantations would find various ways to undermine or even deny that such agreement had ever existed.[55]

November 1920: Matsumoto still wants his $5000

But Matsumoto wanted his $5000 payout, and in November he and Saito sailed for Hilo to confront Miyamura directly. Miyamura sent word after several days that he unfortunately would not be able to meet with them. At this point, Matsumoto was informed that the Federation would be meeting in Honolulu on November 23 at the Kyorakukan restaurant with the private cottage and bath, as usual. He decided to confront them there, purportedly to ask Tsutsumi why the Federation was spending over $2000 a month for newspaper printing, when Samuel Gompers, head of the AFL on the U.S. mainland, was spending only $300.[56] Supposedly, Tsutsumi responded, “you are only a farmer, you better not say anything and go back and keep quiet,” at which point an altercation erupted—as they so often did around Matsumoto—with Matsumoto grappling with Tsutsumi as someone else in the crowd to Matsumoto’s left hit him over the head with a bottle.[57]

Matsumoto complained to the police about the assault. Almost immediately afterwards, he was paid a visit at the hotel where he was staying by Seito Kondo, a pool hall owner who had no official role with the Federation but was described in the English-language press as its “man Friday.”

According to Matsumoto, Kondo

told me that “you already made complaint about this assault,” and he asked me if I am going to disclose the dynamiting matter. . . . I told him I am going to confess. I told him that “some of the officials of the association is not right and I am going to fight them.”. . . He told me to wait. “I am going to have talk with Baba and we will satisfy you,' and asked me to wait."[58]

Kondo later returned with Baba, giving Matsumoto $300 for his hotel expenses and his head injury, but it was obvious at this point that the $5000 would not be forthcoming. Matsumoto, still infuriated about the assault at the Kyorakukan, found Murakami at the Ewa Plantation and informed him that, since the promised money had not been paid, he and Saito were going to give themselves up and that Murakami should as well. Murakami agreed to meet Matsumoto that night at the hotel where he and Saito were staying. As they were talking, a Detective McDuffie from the Honolulu police suddenly poked his head in from the next room.

"You have given this information—in connection with the putting powder on Sakamaki's house—to McDuffie to send us to jail," shouted Murakami. "Do you think that I could move McDuffie?" replied Matsumoto. "He came [so we could] give ourselves up."[59]

(Cont’d). Next week, the conspiracy trial!

[1] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 138-229.

[2] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 19.

[3] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 18.

[4] James William Morley, The Japanese Thrust into Siberia, 1918 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1957), available at https://archive.org/details/japanesethrustin0000morl/mode/2up (viewed April 14, 2025), at 3-4.

[5] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 72.

[6] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 220.

[7] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 221.

[8] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 223.

[9] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 47.

[10] John E. Reinecke, The Filipino Piecemeal Sugar Strike of 1924-1925 (University of Hawai’i Press, 1996), at 4-5.

[11] “Manlapit is first Filipino to be admitted,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, June 7 1919, p. 9; “Manlapit case is under consideration,” Honolulu Star Bulletin, June 17, 1919, p. 18; “Manlapit refused license to practice,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, June 18, 1919, p. 1.

[12] “Filipinos urged to unite to get increased wages,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, September 1, 1919, p. 1.

[13] “Hilo Filipinos to Join Labor Union,” Hilo Daily Tribune, November 19, 1919, p. 5.

[14] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 49.

[15] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 46.

[16] Margaret MacMillan, Paris 1919: Six Months that Changed the World (Random House, 2003), at 400, available at https://bnk.institutkurde.org/images/pdf/EJNCB23UK7.pdf (viewed May 2, 2025).

[17] MacMillan at 408.

[18] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 50.

[19] MacMillan, at 403-04.

[20] Andrew Boyd, British Naval Intelligence Through the Twentieth Century (Seaforth Publishing, 2020), at 281.

[21] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 50-51.

[22] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 79.

[23] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 56-57.

[24] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 62.

[25] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 147.

[26] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 54.

[27] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 55.

[28] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 56.

[29] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 61.

[30] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 63-64/.

[31] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 65.

[32] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 66.

[33] “Sugar Crop is Heavily Insured Against Damage,” Honolulu Star-Advertiser, February 12, 1920, p. 2.

[34] Quoted in Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 67.

[35] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 174.

[36] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 76-78.

[37] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 58.

[38] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 70.

[39] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 70.

[40] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 96.

[41] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 109.

[42] Quoted in Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 110.

[43] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 94.

[44] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 151.

[45] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 16 1.

[46] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 220.

[47] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 168.

[48] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 174-77.

[49] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 220.

[50] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 220.

[51] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 187.

[52] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 153-54.

[53] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 2-3.

[54] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 155.

[55] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 119.

[56] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 156.

[57] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 157-58.

[58] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 158.

[59] Umezawa Duus and Peter Duus, The Japanese Conspiracy: The Oahu Sugar Strike of 1920 (University of California Press, 1999), at 160.