Way back in this post:

I took a pre-1898 inventory of all the collection disciplines that today are associated with the U.S. intelligence community: SIGINT, IMINT, MASINT, HUMINT, OSINT, GEOINT, and identity intelligence/identity resolution, looking at what existed prior to the Spanish-American War of 1898 and what happened to them afterwards. Starting with this post:

I’ve been examining in my Sunday posts how each of these disciplines evolved from after the Spanish-American War and primarily how they were affected by the next great clash between European colonial powers, World War I.

Today I finally turn to the very last category I examined in my pre-1898 inventory: enforcement capacity. After this I hope to return to a few of my fun, short posts before moving on to the next phase of my research.

America’s First Century: Lack of standing military capacity

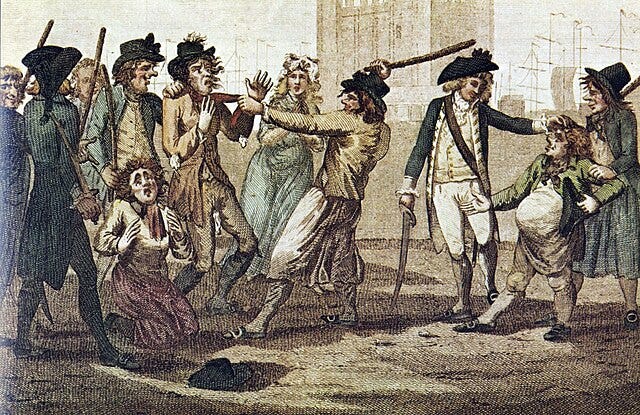

The last time the United States invaded Canada, it was over the issue of forced conscription. Specifically, the British, who refused to recognize U.S. citizenship, were forcibly impressing Americans into the Royal Navy. When the war against Napoleon began, the British were forced to add new warships to their fleet, and the number of sailors needed to man them all increased from 16,600 in 1793 to 119,000 by 1797. The demand for sailors outpaced supply by two to one, and the British made up the difference by sending club-wielding naval press gangs to “scour[] ships and wharves, streets and taverns, inns and even homes to grab mariners and hauled them away for forcible enlistment. Their catch entered a harsh, dangerous, badly fed and underpaid servitude that usually lasted until the sailor died or the war ended.”[1]

The British also pursued its army and navy deserters from U.S seaports and the Canadian border well into U.S. territory. They were occasionally pushed back by angry mobs but experienced no significant military response from the United States, which by 1807, under the leadership of President Jefferson and the Republican Congress who were seeking to cut taxes and reduce the national debt, had a federal army consisting of 3,287 men.[2] “In 1811 the United States government spent only one dollar per capita, a mere twenty-fifth of the public expenditures in Great Britain.”[3]

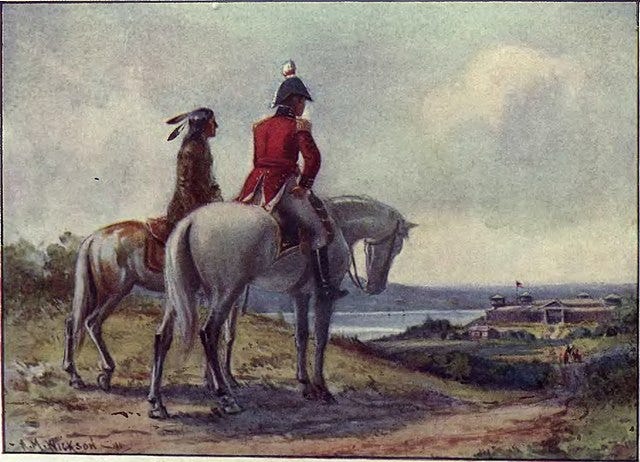

The Republicans decided to launch a land invasion of Canada in 1812 instead of a naval confrontation, because they assumed this would be cheaper than trying to build a navy to compete with Britain’s,[4] which by 1812 had a total of 500 ships to the Americans’ sixteen.[5] A force of 2,500 American troops, mostly volunteer militia, invaded upper Canada, only to quickly surrender, terrorized by the war whoops of Britain’s Indian allies.[6]

Due to low pay and harsh conditions, as well as the exclusion of freed Blacks, the size of the regular U.S. Army never exceeded 40,000 men at any point during the war; while “many more Americans served for a few weeks or months in the militia…they were virtually useless.”[7] The War of 1812 was fought to a draw on the battlefields and eventually settled in the 1814 Treaty of Ghent, but not before the British had burned down the White House, from which First Lady Dolly Madison famously scrambled to save an 8-foot tall portrait of George Washington that now hangs in the National Portrait Gallery.[8]

A surveillance state requires not only a certain number of people collecting, retrieving, and analyzing intelligence, but some sort of reliable, centralized state apparatus to take action based on this intelligence, including through the use of force where necessary. The War of 1812, however, marked only the beginning of a long tradition of the U.S. Government trying to maintain order, defend its borders and enforce its laws while relying on primarily state and local authorities, augmented by unpredictable coteries of enthusiastic volunteers.

Early U.S. policymakers were particularly leery of maintaining a large standing army, not only because of its cost but because of its threat to civil liberties, and there remain several legal restrictions on deploying the Army domestically. The Third Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, considered so uncontroversial that it has never been tested in the U.S. Supreme Court, provides that “No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.” The Constitution’s Calling Forth Clause invests in Congress, not the Executive Branch, the power of “calling forth the Militia [the modern incarnation of which is the National Guard] to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions.”[9]

The 1807 Insurrection Act enables the President to call forth the regular army or naval forces in cases of insurrection or obstruction of laws.[10] However, the Posse Comitatus Act of 1878, enacted in response to the post-Civil War military occupation of the South and most recently amended in 2021, prohibits the use of the armed forces for civilian law enforcement operations except where expressly authorized by Congress.[11]

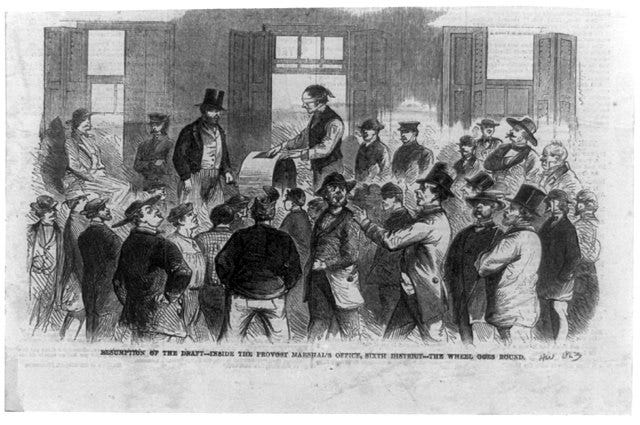

The United States also has strenuously resisted forced conscription for most of its history. For the first 15 months of the Civil War, both the Union and the Confederacy’s forces were entirely reliant on volunteers. As the war dragged on, the Confederacy implemented a draft—which was immediately challenged as an unconstitutional infringement upon states’ rights—and the U.S. Congress followed suit, but only in stages.[12] In July 1862, the United States enacted the Militia Act, which required the enrollment of all eligible males into for future draft calls of their respective governors into the state militias and authorized President Lincoln to call these same militias into federal service for up to nine months (it also allowed the enlistment of Blacks, who by the end of the war would constitute 9 to 10 percent of all Union soldiers).[13] This approach was politically palatable, as it left the governors in charge of their respective drafts as long as they met their quotas.[14] Unfortunately, it also left medical examinations in the hands of local physicians beholden to their own patients and communities, who promptly “granted blanket exemptions to their healthy friends and neighbors.”[15]

In 1863, the U.S. Congress followed up with the Enrollment Act, which enabled the federal government to directly conscript soldiers. A challenge to the constitutionality of the draft was immediately brought in Pennsylvania. In anticipation of the case reaching the U.S. Supreme Court (which it ultimately never did), Chief Justice Robert B. Taney drafted a legal opinion in which he intended to strike down the Enrollment Act as unconstitutional, as it infringed upon Pennsylvania’s right to raise its own militia.[16] Meanwhile, three days after the first draftees were called out of New York City, a mob of mostly Irish laborers decided on a different way to challenge the draft.

Enraged that they should be forced to fight for the abolition of slavery, they attacked the local draft office, set it ablaze, and proceeded to spend a week rioting throughout the city; clubbing police officers, soldiers, and random Black bystanders, several of them to death; and destroying the Colored Orphan Asylum, shouting death threats to “n-rs” as children 12 years of age and under were spirited out the back door.[17] The United States would not attempt another military draft until World War I.

Early 20th century: Professionalization of military and police

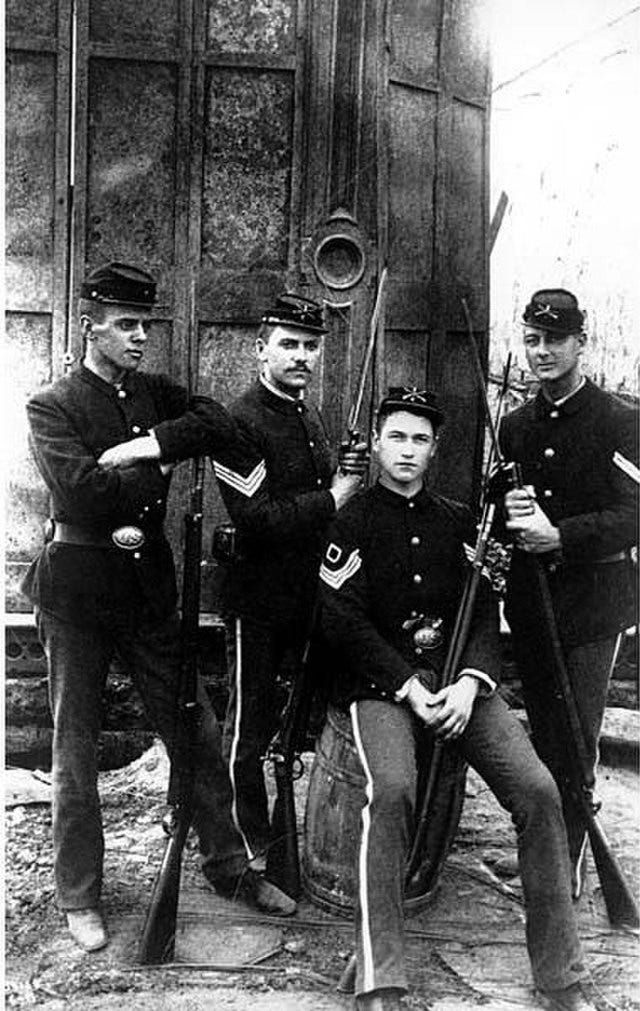

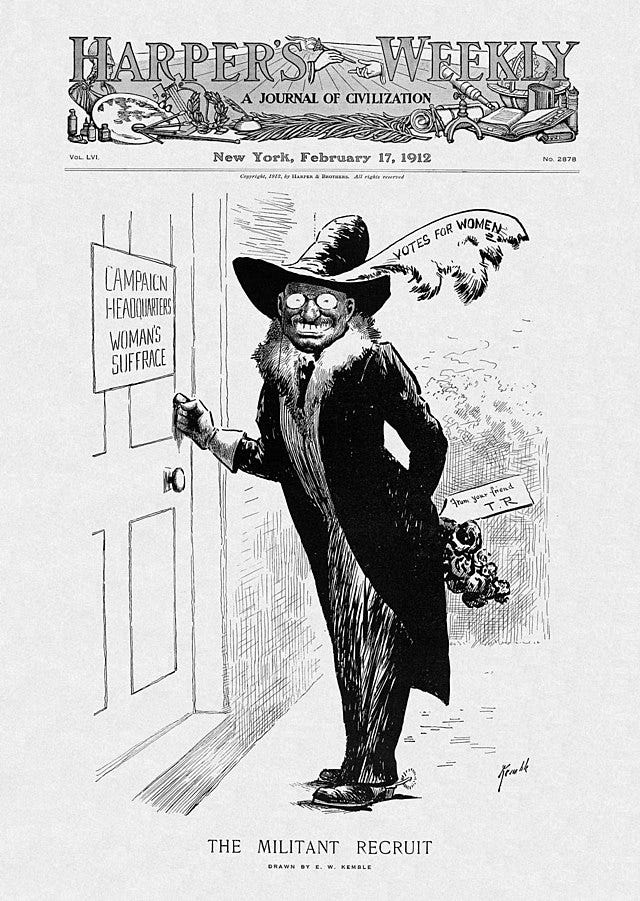

The U.S. Army, Navy and Marines did achieve a level of professionalization during the 19th century. A “profession,” as distinct from an occupation, tends to be a field for which recruitment and performance standards are centrally controlled; requires a formal education; has “a service orientation in which loyalty to standards of competence and to clients’ needs is paramount”; and “is granted a great deal of collective autonomy by the society it serves, presumably because the practitioners have proven their high ethical standards and trustworthiness.”[18] By the turn of the 20th century, this generally described the U.S. armed forces and most definitely did not describe the nation’s police. Accordingly, prominent police reformers, including Teddy Roosevelt, who was appointed to the New York City Police Commission in 1895, enthusiastically promoted the military as a model for instilling discipline in the NYPD, with mixed results.

While Roosevelt only lasted in this position until 1897, going on to distinguish himself on an actual military campaign with the “Rough Riders” in the Spanish-American War, several other Progressive Era reformers also embraced the military analogy.

“The military model and its rhetoric of police reform seemed to offer an alternative paradigm more fitting to what Progressives thought police ought to be doing—fighting a ‘war’ against crime and vice. For example, Progressive politicians, such as then New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson (a great proponent of public administration) and New York City Police Commissioner William McAdoo, compared police in the United States to an army in both method and purpose.”[19]

Of course, as I have previously observed in this post:

the very concept of regulating vice (opium, prostitution, gambling) was something the United States pioneered in the colonial context of the Philippines, and it was vice policing itself that in many instances gave rise to police corruption. Nonetheless, military veterans of the Philippines War were often called upon to militarize U.S. police forces, most notably Marine Corps Major General Smedley Butler, two-time recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor, who in 1924 was appointed as Philadelphia’s Director of Public Safety. By then, Prohibition, the ultimate experiment in vice policing, was resulting in a nationwide spike in organized crime. Butler “gathered the Philadelphia police force in the opera house and delivered speeches urging the cops on to the fight as if they were about to go into battle in the Philippines or France. He boldly offered a promotion to the first cop who killed a gangster.”[20]

U.S.-based initiatives to militarize the police loosely resembled various European models, such as the French gendarmes. The key difference, however, was that European states had a longstanding tradition of centralized state control, whereas in the United States, the disdain for centralized authority “forcibly forbade an armed centralized national police force. In the United States, then, police would come to be militarized but not on a national level, and not without some trepidation. Authority and control would have to remain primarily local.”[21]

Immigration controls, vice regulation and the police state

To a large degree, the coordinating link between federal and local law enforcement came through immigration controls; specifically, the policing of women by other women. Prostitution was one of the major vices that not only came under major scrutiny by Progressive Era reformers both in the United States and the Philippines, and one that came to be strongly associated with the enormous influx of immigrants into major cities. Seven years prior to the passage of the federal Mann Act outlawing the transport of women for purposes of prostitution, in 1903 the New York Council of Jewish Women (CJW) took it upon themselves to begin “inspecting” Jewish steerage passengers at Ellis Island in partnership with federal immigration authorities. Along with the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS) and various Anglo-Saxon Protestant reform allies, the CJW assisted women through the processes at Ellis Island, helping them make connections to local family members or transportation elsewhere, but they also worked to “morally” assimilate immigrants. This entailed interviewing all single women between 12 and 30 years old. The CJW acquired the power to “detain” such women at Ellis Island, “and often did so until it was verified that their destinations and escorts were suitable with regard to the regulation of immigrants’ post-settlement behavior.”[22]

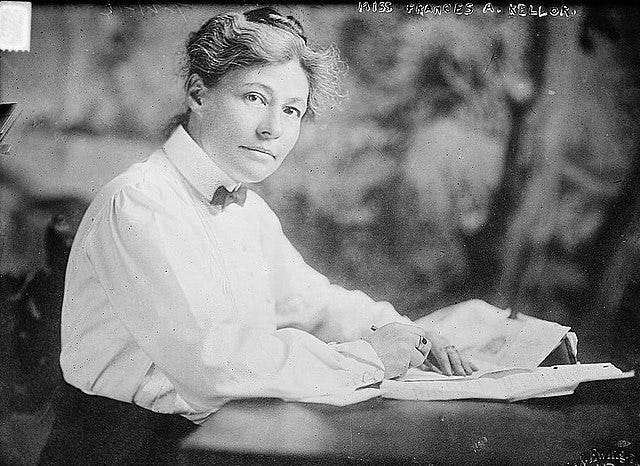

These private aid organizations, moreover, also took it upon themselves to monitor the immigrants’ “post-settlement behavior.” Between 1906 and 1908, CJW representatives made 4,314 “friendly” visits to young immigrant women, while also offering a range of educational and supervisory projects, such as public sex education promoting the sanctity of marriage, dance hall regulation through licensing, carefully supervised alternative leisure venues, and other measures design to “prevent or manage women’s fall from virtue.”[23] Sociologist and lawyer Frances Kellor, who in 1909 became director of the New York State Bureau of Industries and Immigration, began meeting with New York City Immigration Commissioner Robert Watchorn in late 1906 in furtherance of her suspicions that immoral women were entering the country clandestinely.

By that point, the federal Immigration Act of 1891 (which I alluded to briefly here):

was already authorizing the deportation of aliens who, within one year of arrival, had become public charges from causes allegedly existing prior to their landing. In 1907, Kellor reached out to President Roosevelt directly, and her advocacy eventually led to a provision in the 1907 Immigration Act providing that “any alien woman or girl [found to be a prostitute] within three years after she shall have entered…shall be deemed to be unlawfully within the United States.” The Bureau of Immigration’s implementing instructions made clear that “The fact that an alien, when apprehended, is found practicing prostitution…is so strong an indication that the alien was a prostitute…at the time of entry…as to raise a presumption of fact that such alien belonged to one of the excluded classes in question at the time of arrival.” In other words, “[i]mmigrant immorality after landing was sufficient evidence of immorality upon landing.” By 1915, hundreds of women had been arrested and then deported from the United States pursuant to these provisions.[24]

Who was carrying out all these arrests? The 1907 Immigration Act led to federal immigration officials in New York City directly aiding the local police in raids on houses of ill repute in the Tenderloin District. Helen Bullis, the “Special Inspectress” for the Immigration Service at Ellis Island, coordinated regularly with both Watchorn and the Fourth Deputy Police Commissioner of New York City, working in tandem with the NYPD to initiate raids and prosecutions of immigrations involved in prostitution. The amendments to the Immigration Act continued to be reflected in federal law as late as 1990, providing that immigrants “engaged in prostitution within 10 years” of entry were deemed “inadmissible at time of entry” and thus deportable.[25] Bullis also uncovered numerous instances of corruption and collaboration with prostitutes by observing proceedings in New York City’s Night Court, where she insisted on inserting the question “How long have you been in the U.S.?” for all immigrant women arrested on morals charges. She found that some court clerks were advising women on how to answer that question in order to avoid being turned over to Ellis Island. In 1909, federal-local cooperation unearthed an alleged “racket” in the Tenderloin involving false documentation of landing dates, with the help of a night court clerk who had also worked at Ellis Island.[26]

(By the way, if you are at all shocked at what women are willing to do to other women, definitely read this short post of mine):

Thus, well prior to World War I, federal immigration law and immigration authorities were standardizing local criminal justice systems, at least in New York City, in the absence of any large, reputable or viable federal police agency. In the Pacific Northwest, by contrast, and as we have seen, U.S. immigration officials began collaborating directly with British-Canadian intelligence agents and acting at the behest of organized labor in order to try to bar Hindu and Sikh laborers from entry.

With the outbreak of the war in Europe in 1914, the NYPD, as well, found itself dependent upon British intelligence for help with the German sabotage and espionage threat, as the U.S. Secret Service and Bureau of Investigation (BOI) at the U.S. Justice Department battled between themselves for the position of federal lead on these activities (which I also talked about here):

By 1917, the BOI was still so vastly understaffed for its wartime counterintelligence mission that it was forced to rely heavily on private, vigilante-type organizations such as the American Protective League (which I discussed here):

World War I and the military draft

But federal personnel resources, over the next two years, were about to see a dramatic uptick for the duration of U.S. involvement in World War I. The National Defense Act of 1916 had authorized the growth of the U.S. Army to 165,000 and the National Guard to 450,000 by 1921. It also considerably reorganized and standardized the personnel standards and training National Guard, which up to that point had been characterized by huge variations in standards from state to state.[27] However, the new numbers authorized still represented but a fraction of what would be needed to fight in the war in Europe. By 1917, the volunteer Army had only expanded from 100,000 to 121,000, and the National Guard from 115,000 to 118,000. The ever-pugilistic Teddy Roosevelt, who now insisted on being addressed as “Colonel Roosevelt” rather than “Mr. President,” was threatening to upstage Woodrow Wilson (the two loathed one another) by organizing his own volunteer infantry division, led by his good friend and fellow Rough Rider veteran Major General Leonard Wood. This resolved any remaining qualms Wilson might have had about supporting a draft.[28]

Thus, on May 18, 1917, Congress passed the Selective Service Act, authorizing President Wilson to (1) expand the size of the Regular Army, including by both provisional and permanent appointments of officers; (2) draft into the military service any or all members of the National Guard; and (3) draft up to a million men, leaving largely to the President’s discretion how and when to implement the draft’s requirements.[29] Unlike the Civil War draft, this one would not allow for substitutions or for the payment of $300 to avoid one’s military obligations, which had been the source of a great deal of class-based resentments and one of the many instigating factors behind the New York City draft riots of 1863.

On June 5, 1917, ten million men between the ages of 21 and 31 registered for the draft at courthouses and city halls across the country, creating a bonanza today for genealogists looking for biographical information on their ancestors.[30] A total of 24 million draft registration cards remain accessible today through the National Archives, digitized and searchable through genealogy websites like familysearch.org[31]

The draft also resulted in the development of large-scale mental tests, yielding some interesting demographic data and setting the stage for standardized testing in public education. In April 1917 the American Psychological Association and the Committee for Psychology of the National Research Council formed several committees to study how their field could make a contribution to the war effort.[32] Based on these committees’ advice, the Army’s Medical Department formed a Division of Psychology that devised tests initially aimed at “the prompt elimination of recruits whose grade of intelligence [was] too low for satisfactory service.”[33] Eventually two tests were developed: the alpha test, for those who were able to read and write English well, with a beta test developed later to meet an “unexpected demand for the examination of subjects with low literacy and extreme unfamiliarity with English.” The exams resulted in grades of A through E, with grades of D- and E assigned to men who were deemed below 10 years in “mental age.”[34]

These exams were given to 1,726,966 men, with results analyzed through a Hollerith tabulation machine.[35] Black men on the whole were found to have lower mental ratings on these tests than white men, but Black northerners scored higher than Black southerners[36] as well as many white Southerners, suggesting the real problem was not racial but a north-south divide in the quality of education. Following the war, those who spearheaded the work began promoting the tests as a means of assessing students in high schools and higher education, as they had also studied officer candidates in the Students’ Army Training Corps and offered the tests to several colleges. One of the many observations they gathered from testing college students was that, “[w]hile the median scores made by the women are in every case a few points lower than the median scores for the men…the differences are so small that they may be regarded as insignificant.”[37]

For federal law enforcement entities, the war did not immediately result in dramatic increases in personnel. In 1916, Secretary of State Lansing had created a Bureau of Secret Intelligence headed by a Chief Special Agent, primarily to handle issues involving fraudulent passports and visas (some of which were being used by German spies). But even as late as 1921, the Chief Special Agent had no more than 25 agents working for him.[38]

Enemy aliens and the growth of the Justice Department

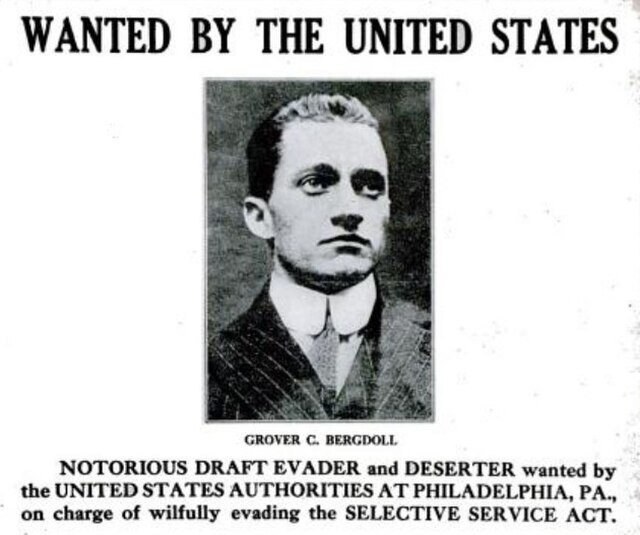

As for the Bureau of Investigation, in 1915, it had only 219 agents. After the United States entered the war, the BOI was allowed to expand but only to 400 agents, still “a puny squad for policing more than 1,000,000 enemy aliens, protecting harbors and war-industry zones barred to enemy aliens, aiding draft boards and the Army in locating draft dodgers and deserters, and carrying on the regular duties of investigating federal law violators.”[39]

This is again why it became so dependent on the private American Protective League, including with regard to the “slacker raids” that began the night of March 16, 1918. “Nothing aroused the rage of middle-aged APL members more than young men who might be failing to fight,” and that night, a convoy of trucks pulled up in front of a row of boarding houses and cheap residential hotels, carrying 120 APL members and 65 members of the Minnesota National Guard. The APL members went door to door, demanding that each man show his draft card, while the Guardsmen stationed themselves at the building’s entrance.[40]

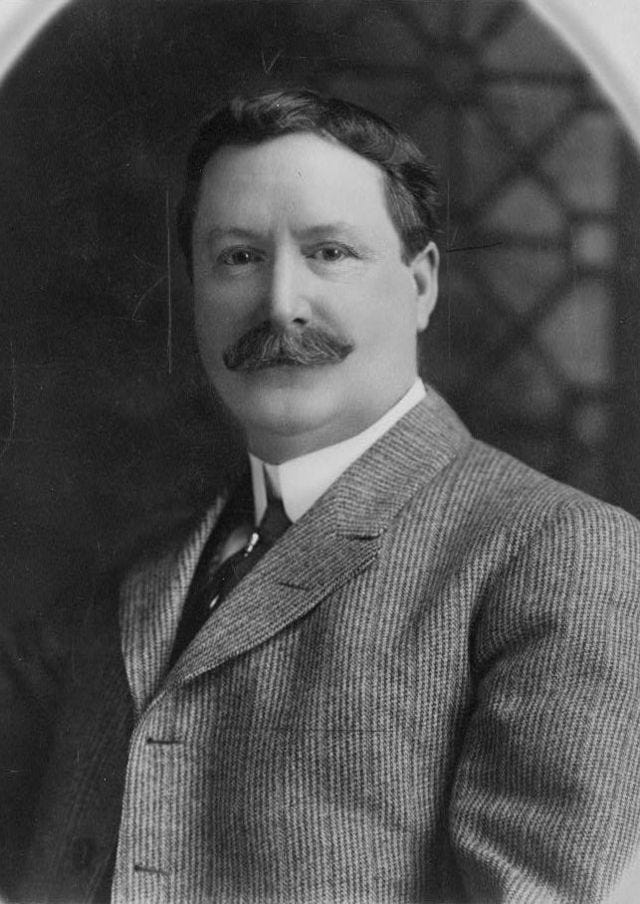

But larger changes were afoot at the Department of Justice (DOJ) if not the BOI. The Trading with the Enemy Act, enacted in October 1917,[41] provided for the creation of an Alien Property Custodian within the DOJ, whose purpose was to receive, administer, and account for “all money and property in the United States due or belonging to an enemy or ally of enemy…” Wilson appointed former Congressman A. Mitchell Palmer to the post, which came with its own investigative bureau. [42] Palmer found the job “an ambitious politician’s dream,” enabling him to sell off German and Austro-Hungarian companies at low prices to influential Democratic Party funders. These same funders would later support his successful bid to replace Watson as Attorney General in March 1919.[43]

A. Mitchell Palmer, J. Edgar Hoover, and the Red Scare

Meanwhile, the ambitious young attorney J. Edgar Hoover, who had spent the war putting his Library of Congress experience to work compiling files on half a million enemy aliens, had found himself following the November 1918 armistice with Germany, with little or nothing to do in a peacetime Department of Justice.[44] But there were already new foes who could serve as a worthy target for Hoover’s tireless work ethic, and new alliances to be made with municipal law enforcement agencies that again capitalized upon the ability of immigration policy to bridge the federal-local divide. The same month that Palmer was appointed Attorney General, Vladimir Lenin, now the undisputed head of Soviet Russia, announced the creation of the Third International, or Comintern, the goal of which was to foment a global Communist revolution. Within a few short months, Palmer would create a new Radical Division to fight Communists, with Hoover at its helm.

Palmer, a Pennsylvania Quaker, was unsure of his authority to bring federal criminal prosecutions against the nation’s political radicals—anarchists, anti-war protesters, and the International Workers of the World—now that the nation was at peace.[45] Anarchists had long been a target of urban police surveillance dating back to the 1901 assassination of President McKinley by an anarchist. The NYPD had formed an Anarchist Squad in 1906, “focusing on harassing and arresting anarchists on pretexts, intimidating hall owners, and blocking the distribution of the anarchist journal Mother Earth.”[46]

Strikes and associated labor agitation also had long been associated with the potential for violence, dating back to the Haymarket bombing of 1886, and many urban police forces also formed “red squads” to deal with labor activists starting around 1900, typically with the strong support of the local business community.[47] Within the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD), for example, the red squad “served as the operational arm of the anti-union crusade of the Merchants and Manufacturers Association (M&M), a confederation of over 80 percent of Los Angeles’ business firms, whose stated purpose was to ‘break the back of organized labor’ and make the city ‘a model open shop town’ in order to ensure its members a cheap supply of labor and to attract new industries.”[48] Local police forces could suppress and criminally prosecute political expression and association in ways that the federal government could not, as the Supreme Court had not yet held that the First Amendment offered protection against non-federal action.

Federal immigration law, however, was another matter. In October 1918, the U.S. Congress had enacted yet another Immigration Act, broadening the definition of “anarchist” and expanding the possibilities for deportation of long-term residents, a convenient new way to rid the nation of its undesirables, since “[e]verybody knew that places like Italy, Russia, and eastern Europe were the source of a large proportion of the nation’s anarchists and socialists.”[49] Palmer was not sure he wanted to carry out a deportation campaign, either, but shortly after his appointment as Attorney General, he appointed Hoover as his special assistant, charged with answering queries about immigration and deportation law and liaising with the Labor Department.

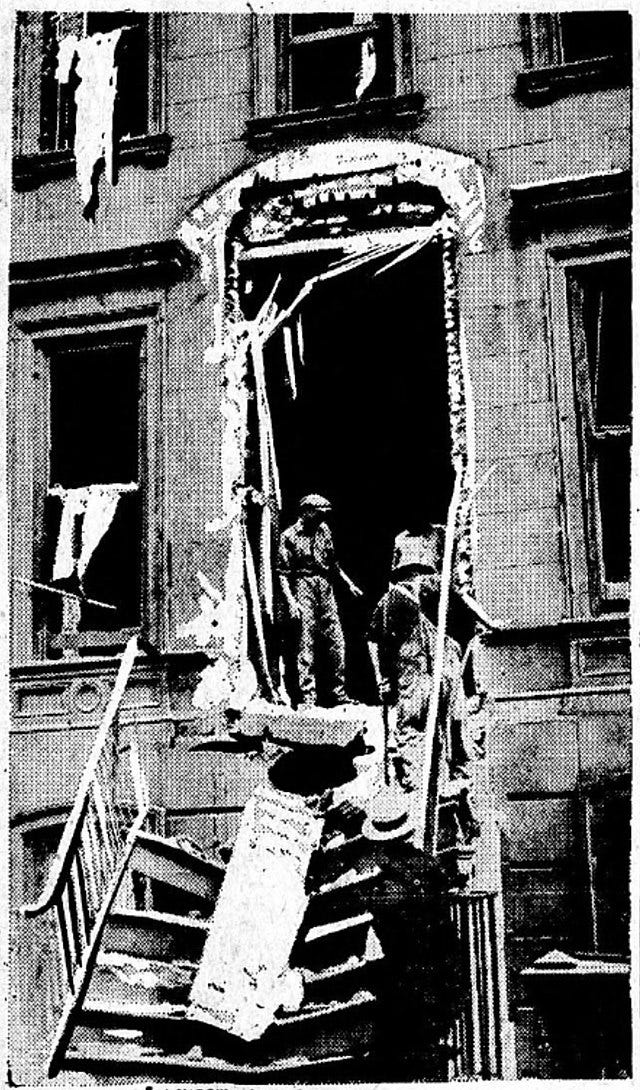

Then, in April 1919, a series of bombs began showing up in the mail, arriving at the houses of prominent politicians—starting with Seattle mayor Ole Hanson, who had recently crushed a local strike, followed by Senate Thomas Hardwick, who had sponsored the Immigration Act of 1918. A total of 30 bombs were then spotted by postal employees scattered throughout the postal system. Palmer initially urged calm in response to the mail bombs, most of which had failed due to the bombers’ incompetence. His attitude, however, changed dramatically after the night of June 2, when a slightly more competent bomber managed to destroy the entire front of Palmer’s house, Palmer himself having narrowly avoided death or injury by retiring for the night upstairs shortly before the explosion. “Assistant secretary of the Navy Franklin Roosevelt came running from his house across the street and found Palmer ‘theeing’ and ‘thouing’ on the lawn, the shock of the blast having summoned forth his childhood Quakerisms. Human limbs and bits of flesh covered the yard, the remains of the man who had transported the bomb. Scattered across the lawn was a series of pink paper pamphlets titled ‘Plain Words’ and signed by ‘The Anarchist Fighters.’”[50]

The Palmer Raids

Forever a changed man, Palmer immediately began planning a deportation campaign with Hoover now firmly in his inner circle. On July 1 he appointed Hoover the head of the Justice Department’s new Radical Division, technically a part of the BOI, but without imposing on Hoover any obligation to conduct field investigations or fulfill the other duties required of BOI agents.[51] Hoover immediately set about revamping the BOI’s filing system along lines strikingly similar to those implemented by Ralph Van Deman in the Philippines in 1901: all field reports were directed to Hoover’s small team of clerks, who drew up index cards classifying each report by subject name, state, city, organization, ideological orientation, and event. By the fall, the Radical Division’s filing cabinets held 50,000 cards, and more than one million by the end of Hoover’s first year.[52]

Despite all these efforts, however, by October 1919 there had been no deportations, not to mention no investigative leads in all of the bombing cases (the bombers would never, in fact, be conclusively identified). As President Wilson recovered from a stroke, Congressional pressure on Palmer mounted for some tangible results.[53] Hoover began requesting deportation warrants from the Labor Department as Palmer’s team planned a raid, selecting as their first target the Union of Russian Workers. Hoover’s team produced 400 affidavits by sworn federal agents in order to support the raids the night of November 7, 1919. “Over several hours, federal agents and local deputies forced their way into meeting halls and private homes in eighteen cities, arresting everyone on the premises [a total of 1,182 men and women, some of whom were pulled out of their beds] and seizing literature, banners, accounts books, weapons, and membership lists.”

Palmer immediately claimed public credit to near-universal acclaim, and Hoover began planning an even bigger raid, this time setting his sights on the Communist Party and the Communist Labor Party.[54] On January 2, 1920, with Hoover now “indisputably in charge of coordinating the operation,”[55] executed another series of night raids across 30 U.S. cities, casting an ever-widening net. In Detroit, for example, where 800 people were arrested, “raiders entered a restaurant popular with socialist, arresting dancers, musicians, waiters, cooks, and everyone eating dinner.”[56]

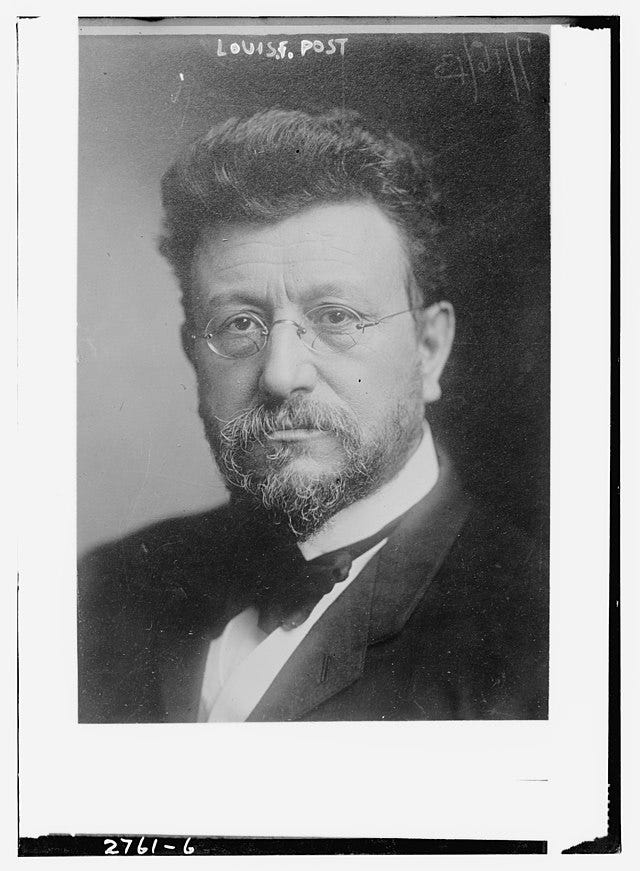

What neither Palmer nor Hoover had counted on was a growing concern at the Labor Department—by one senior official in particular—that the raiders had overstepped their legal bounds. There was something inherently wrong with the Justice Department arresting 1,182 people based on only 400 Labor Department warrants, which eventually came to the attention of the Labor Department’s third-ranking official, Louis F. Post. Post, a founding member of the NAACP, had once run a magazine called The Public, which had “denounced the American colonization of the Philippines, the unchecked power of big business, and racial discrimination, while supporting votes for women, free speech, and unrestricted immigration.”[57]

In March 1920, Labor Secretary William B. Wilson went on personal leave, and because his deputy secretary was running for the Senate, this placed Louis Post in charge of the entire Labor Department for a period of six weeks. During those six weeks, Post ordered all department officials to send all deportation cases directly to him. He immediately noticed not only that many arrests had been made without Labor Department warrants, but even those warrants that had been issued were frequently based on faulty information. He invalidated nearly 3,000 of those arrests, and, out of 2,435 deportation cases involving Communists forwarded to Labor from the BOI, he rejected over 80 percent.[58]

Post’s actions infuriated Palmer, Hoover, and their anti-immigrant allies in Congress. Hoover had agents gather intelligence on his critics, “a practice that would later become routine,” and withdrew bureaucratic support from the Labor Department.[59] Post, however, stood firm. Secretary Wilson, upon his return, backed his subordinate when the conflict was finally brought to the attention of President Wilson, who was also now back from the Versailles Conference in Paris but too weakened in mind and body to act decisively in favor of one side or the other. Reportedly, President Wilson suggested to Palmer that he needed to back off from his fervent Red-hunting.[60] If so, Palmer did not follow this advice, as he and Hoover now prepared the nation for an imminent Communist uprising that was to take place nationwide on May 1.

It was the complete failure of the May 1, 1920, uprising to amount to much of anything, after weeks of Justice Department hype, that set into motion the reversal of political fortunes for Palmer. In anticipation of “the nationwide mayhem” that Palmer predicted, New York canceled all police leaves and placed all three shifts of the city’s 11,000 officers and detectives on duty for all of May 1 and the following day. Trucks mounted with machine guns were placed strategically throughout Boston, while “360 suspicious characters” were preemptively detained on April 30 in Chicago.[61]

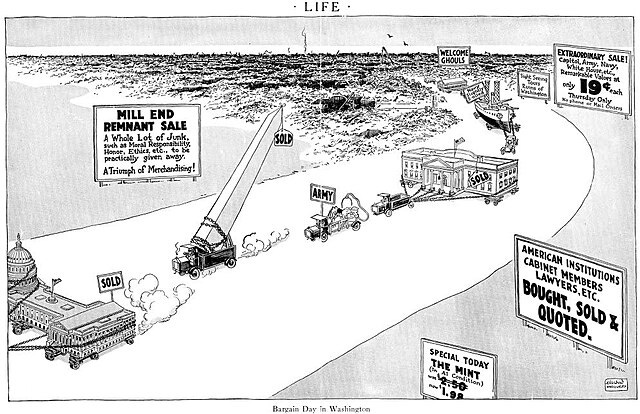

When nothing then happened, aside from the usual, peaceful left-wing meetings that had accompanied May Day observances by the labor movement for decades, the nation’s major newspapers for the first time broke ranks with Palmer’s Red Scare, and even began mocking him with political cartoons.[62] And when Louis Post showed up for what was anticipated to be a public, political flagellation by Palmer’s allies on the House Rules Committee, his sharp wit carried the day. As a committee questioner at one point observed “I am not impressed with the truth of everything I hear,” Post shot back, “Neither am I. If I had been I would have deported every man that the detectives arrested.”[63]

By the time of the Democratic National Convention that fall, Palmer’s bid for presidential nominee was effectively over. Somewhat unsurprisingly, he had trouble gaining support from organized labor.[64] Leonard Wood fared no better in his bid for the Republican nomination. Both men were now seen to be out of step with the times, and the 1920 presidential contest came down to two Ohioans: Governor James M. Cox and Senator Warren G. Harding.

But this was not the end for the BOI, which would experience even more growth during the era of Prohibition. The fact that Hoover somehow escaped the political fate that befell Palmer probably had much to do with his lifelong effort to downplay his central role in the Palmer raids, particularly the raids of January 3, 1920. President Harding’s incoming Attorney General, Harry Daugherty, made no secret of his intention to replace the “anarchist chaser” William J. Flynn, then head of the BOI, with the private detective William J. Burns. Knowing this, Hoover, who had worked with Burns on the deportation of anarchist Emma Goldman in 1919 and again with respect to a bombing on Wall Street in the fall of 1920, went out of his way to assist the Burns agency with its bombing investigation. Daughterty followed through on his plans to appoint Burns in August 1921, and a mere four days later, Burns appointed Hoover as his assistant director.[65] Burns placed Hoover in charge of establishing and coordinating a national system for organizing criminal fingerprints, at which he naturally excelled.[66]

President Harding then suddenly collapsed and died in San Francisco on August 2, 1923. In the wake of his death, a bribery scheme involving the Teapot Dome naval oil reserve in Wyoming quickly came to light, engulfing both Daugherty and Burns, who had shielded the oilmen involved from legal scrutiny.

In late March 1924, President Calvin Coolidge asked for Daugherty’s resignation, with Burns stepping down six weeks later. The 29-year-old Hoover, who had somehow evaded yet another scandal, was now the head of the Bureau that he would lead until his death in 1972.[67]

[1] Alan Taylor, The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, and Indian Allies (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010), at 103.

[2] Alan Taylor, The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, and Indian Allies (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010), at 112.

[3] Alan Taylor, The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, and Indian Allies (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010), at 119.

[4] Alan Taylor, The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, and Indian Allies (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010), at 140.

[5] “War of 1812 Overview,” U.S.S. Constitution Museum, available at https://ussconstitutionmuseum.org/major-events/war-of-1812-overview/ (viewed March 11, 2025).

[6] Alan Taylor, The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, and Indian Allies (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010), at 153-66.

[7] Alan Taylor, The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, and Indian Allies (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010), at 328-29. This was out of a population of 1,120,000 white men of military age, 18 to 45 years old.

[8] “Dolley Madison Rescues George Washington,” George Washington’s Mount Vernon, available at https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/artwork/dolley-madison-comes-to-the-rescue (viewed March 11, 2025).

[9] U.S. Const., Art. 1, Sec. 8, Clause 15.

[10] Insurrection Act of 1807, ch 39, 2 Stat 443.

[11] 18 U.S.C. § 1385. Use of Army, Navy, Marine Corps, Air Force, and Space Force as posse comitatus: Whoever, except in cases and under circumstances expressly authorized by the Constitution or Act of Congress, willfully uses any part of the Army, the Navy, the Marine Corps, the Air Force, or the Space Force as a posse comitatus or otherwise to execute the laws shall be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than two years, or both.

[12] James W. Geary, We Need Men: The Union Draft in the Civil War (Northern Illinois University Press: DeKalb, 1991), at 3-5.

[13] James W. Geary, We Need Men: The Union Draft in the Civil War (Northern Illinois University Press: DeKalb, 1991), at 28-30.

[14] James W. Geary, We Need Men: The Union Draft in the Civil War (Northern Illinois University Press: DeKalb, 1991), at 32-35.

[15] James W. Geary, We Need Men: The Union Draft in the Civil War (Northern Illinois University Press: DeKalb, 1991), at 38.

[16] Matthew Ivey, “The Broken Promises of an All-Volunteer Military,” Temple L. Rev. Vol. 86 No. 3 (2014), 525- 76, at 533 (citing Kneedler v. Lane, 3 Grant 523 (Pa. 1863)(in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court); and Roger B. Taney, “Thoughts on the Conscription Law of the United States,” in Martin Anderson, ed., The Military Draft, at 207-218).

[17] Adrian Cook, Armies of the Streets: The New York City Draft Riots of 1863 (University of Kentucky Press: 1974), at 55-78, available at https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/232566043.pdf (viewed March 14, 2025).

[18] Matthew Moten, “Who is a Member of the Military Profession?” Joint Forces Quarterly, Issue 62, 3d quarter 2011, available at https://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/jfq/jfq-62/jfq-62_14-17_Moten.pdf (viewed March 15, 2025).

[19] Wiliam Thomas Allison, “The Militarization of American Policing: Enduring Metaphor for a Shifting Context,” in Stacy A. McGoldrick and Andrea McCardle, eds., Uniform Behavior: Police Localism and National Politics (Palgrave Macmillan; 1st ed. 2006 edition), at 10.

[20] Wiliam Thomas Allison, “The Militarization of American Policing: Enduring Metaphor for a Shifting Context,” in Stacy A. McGoldrick and Andrea McCardle, eds., Uniform Behavior: Police Localism and National Politics (Palgrave Macmillan; 1st ed. 2006 edition), at 16.

[21] Wiliam Thomas Allison, “The Militarization of American Policing: Enduring Metaphor for a Shifting Context,” in Stacy A. McGoldrick and Andrea McCardle, eds., Uniform Behavior: Police Localism and National Politics (Palgrave Macmillan; 1st ed. 2006 edition), at 11.

[22] Val Marie Johnson, “’Arriving for Immoral Purposes’: Women, Immigration and the Historical Intersection of Federal and Municipal Policing,” in Stacy A. McGoldrick and Andrea McCardle, eds., Uniform Behavior: Police Localism and National Politics (Palgrave Macmillan; 1st ed. 2006 edition), at 28.

[23] Val Marie Johnson, “’Arriving for Immoral Purposes’: Women, Immigration and the Historical Intersection of Federal and Municipal Policing,” in Stacy A. McGoldrick and Andrea McCardle, eds., Uniform Behavior: Police Localism and National Politics (Palgrave Macmillan; 1st ed. 2006 edition), at 30.

[24] Val Marie Johnson, “’Arriving for Immoral Purposes’: Women, Immigration and the Historical Intersection of Federal and Municipal Policing,” in Stacy A. McGoldrick and Andrea McCardle, eds., Uniform Behavior: Police Localism and National Politics (Palgrave Macmillan; 1st ed. 2006 edition), at 32-33.

[25] Val Marie Johnson, “’Arriving for Immoral Purposes’: Women, Immigration and the Historical Intersection of Federal and Municipal Policing,” in Stacy A. McGoldrick and Andrea McCardle, eds., Uniform Behavior: Police Localism and National Politics (Palgrave Macmillan; 1st ed. 2006 edition), at 35-36.

[26] Val Marie Johnson, “’Arriving for Immoral Purposes’: Women, Immigration and the Historical Intersection of Federal and Municipal Policing,” in Stacy A. McGoldrick and Andrea McCardle, eds., Uniform Behavior: Police Localism and National Politics (Palgrave Macmillan; 1st ed. 2006 edition), at 37-38.

[27] See National Guard Bureau Historical Services, “Federalizing the National Guard: Preparedness, reserve forces and the National Defense Act of 1916,” June 2, 2016, available at https://www.nationalguard.mil/News/News-Features/Article/789220/federalizing-the-national-guard-preparedness-reserve-forces-and-the-national-de/ (viewed March 15, 2025).

[28] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 71-74.

[29] Selective Service Act or Selective Draft Act, Pub. L. 65-12, 40 Stat. 76, enacted May 18, 1917, text of law available at https://govtrackus.s3.amazonaws.com/legislink/pdf/stat/40/STATUTE-40-Pg76.pdf (viewed March 15, 2025).

[30] See National Archives and Records Administration, “World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918,” available at https://www.archives.gov/files/research/military/ww1/draft-registration/selective-service-cards.pdf (viewed March 15, 2025).

[31] See https://www.familysearch.org/en/search/collection/1968530 (viewed March 15, 2025).

[32] Clarence S. Yoakum and Robert M. Yerkes, Army Mental Tests (Henry Holt and Company, 1920), at viii-ix, available at https://archive.org/details/armymentaltests013695mbp/page/n11/mode/2up (viewed March 15, 2025).

[33] Id. at x.

[34] Id. at 23.

[35] Id. at 12-16, 162.

[36] Id. at 30; see also discussion in Thomas Sowell, Black Rednecks and White Liberals.

[37] Id. at 170.

[38] Dr. Harold C. Relyea, Congressional Research Service, “The Evolution and Organization of the Federal Intelligence Function: A Brief Overview (1776-1975), contained in Book VI of the Final Report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities,” United States Senate (U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, 1976), at 109-10.

[39] Dr. Harold C. Relyea, Congressional Research Service, “The Evolution and Organization of the Federal Intelligence Function: A Brief Overview (1776-1975), contained in Book VI of the Final Report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities,” United States Senate (U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, 1976), at 95.

[40] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 152-53.

[41] Trading with the Enemy Act, Oct. 6, 1917, 40 Stat. 411, codified at 12 U.S.C. § 95 and 50 U.S.C. § 4301 et seq; available at https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/uscode/uscode1958-01005/uscode1958-010050a002/uscode1958-010050a002.pdf (viewed March 15, 2025).

[42] Dr. Harold C. Relyea, Congressional Research Service, “The Evolution and Organization of the Federal Intelligence Function: A Brief Overview (1776-1975), contained in Book VI of the Final Report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities,” United States Senate (U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, 1976), at 111.

[43] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 302.

[44] Beverly Gage, G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Penguin Books: 2023), at 60.

[45] Beverly Gage, G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Penguin Books: 2023), at 64.

[46] Frank J. Donner, Protectors of Privilege: Red Squads and Police Repression in Urban America (University of California Press: 1992), at 30.

[47] Frank J. Donner, Protectors of Privilege: Red Squads and Police Repression in Urban America (University of California Press: 1992), at 12-30.

[48] Frank J. Donner, Protectors of Privilege: Red Squads and Police Repression in Urban America (University of California Press: 1992), at 33.

[49] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 243.

[50] Beverly Gage, G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Penguin Books: 2023), at 66.

[51] Beverly Gage, G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Penguin Books: 2023), at 67-68.

[52] Beverly Gage, G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Penguin Books: 2023), at 69.

[53] Beverly Gage, G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Penguin Books: 2023), at 71.

[54] Beverly Gage, G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Penguin Books: 2023), at 72-76.

[55] Beverly Gage, G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Penguin Books: 2023), at 79-80.

[56] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 295-96.

[57] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 306.

[58] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 305-08.

[59] Beverly Gage, G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Penguin Books: 2023), at 84.

[60] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 309-13.

[61] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 318-19.

[62] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 321-22.

[63] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 324.

[64] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 329.

[65] Beverly Gage, G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Penguin Books: 2023), at 92.

[66] Beverly Gage, G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Penguin Books: 2023), at 95.

[67] Beverly Gage, G-Man: J. Edgar Hoover and the Making of the American Century (Penguin Books: 2023), at 98-99.