The Internationalists and the Immigration Act of 1924

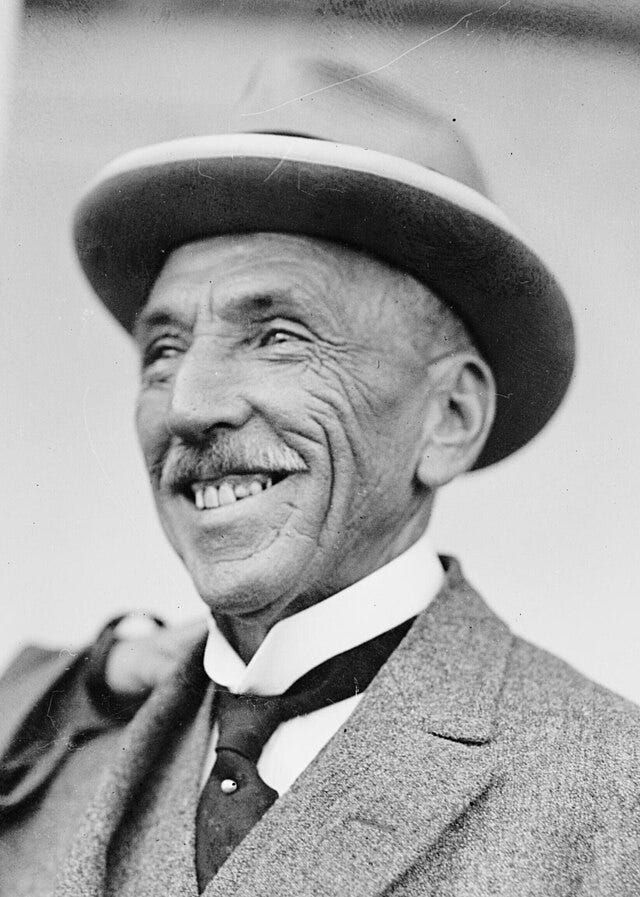

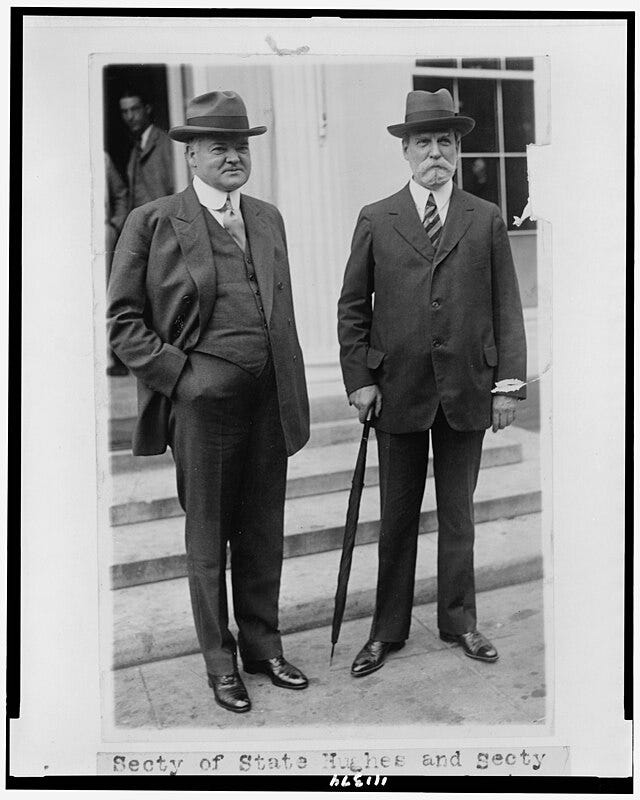

Ambassador Hanihara Masanao and Secretary Charles Evans Hughes

On April 11, 1924, the U.S. Congress, then in the middle of deliberations over the Immigration or Johnson-Reed Act, H.R. 6540, received an extraordinary communication from Japanese Ambassador to the United States Hanihara Masanao, conveyed formally to both the House and Senate by U.S. Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes. The communication indicated that there would be “grave consequences” for bilateral U.S.-Japan relations if Congress followed through on a proposed amendment to the bill, section 12(b), that would effectively end all Japanese immigration to the United States in violation of a 1911 treaty.[1] While the State Department fully supported the ambassador’s efforts to prevent the enactment of Section 12(b)—Hughes, in fact, had sent his own letter to Congressman Albert Johnson explaining the State Department’s objections on February 8, 1924[2]— Hanihara’s communication to Congress achieved the opposite effect, with Senator Henry Cabot Lodge immediately suggesting that the use of the phrase “grave consequences” was in fact a “veiled threat” by Japan against the national sovereignty of the United States.[3] The episode would end with not only the inclusion of 12(b) in the final version of the law, but the recall of Ambassador Hanihara and the effective end of his diplomatic career.

Two weeks ago I offered the back story of the “California contingent” who convinced Congress to enact a wholesale exclusion of all immigration from an Asian Exclusion Zone, clearly targeting the Japanese population of California.

The back story of the internationalists on both the Japanese and U.S. sides, whose efforts to preserve cordial relations between their two nations were to backfire in such spectacular fashion, is the topic of this week’s post.

In 1924, Ambassador Hanihara Masanao was the toast of Washington society and at the pinnacle of his diplomatic career. An unlikely Cinderella story, he had graduated in 1898 from the then-only-16-year-old Tokyo Professional School, which would not be renamed as Waseda University until 1902 and would not receive formal government recognition as a university until 1920. In an era in which the elite bureaucrats of the Japanese Foreign Ministry (the Gaimusho) were more likely to be of noble birth or to have graduated from the more prestigious Tokyo Imperial University (Teidai),[4] in 1899 Hanihara nonetheless passed the rigorous Class I diplomatic examination and entered the foreign service, which would be a source of great pride for Waseda students and fellow alumni for many years to come.[5]

The Origins of the Japanese Foreign Ministry (Gaimusho)

The style of Japanese diplomacy known as Kasumigaseki (named for the neighborhood in Tokyo in which the Gaimusho is located, in much the same manner as “Foggy Bottom” is associated with the U.S. State Department), went hand in glove with the other rapid modernization efforts of the Meiji Era (1868-1912), when Japan ended its centuries-long practice of relative seclusion from the world. The Gaimusho was among the first ministries established in 1868, in large part to rectify what Japan considered its most pressing threat: the unequal treaties that Western powers had imposed on Japan, China and other non-Western nations, which included, most obnoxiously, the Western assertion of extraterritorial jurisdiction over their own nationals on Japanese soil.[6] I discussed this phenomenon way back when, in this post:

Meiji Era leaders decided that the way they were going to do this was to completely absorb the knowledge and ways of the West. They

were…determined to master international law and the rules of conduct between states—which they encountered for the first time and assumed to be universal and eternal. For these leaders, the Chinese translation of Wheaton's The Elements of International Law became their first textbook. According to Yoshino Sakuzo, the Japanese in those days understood international law from the framework of their traditional attitudes. Yoshino wrote that international law and rules were considered to be identical to moral codes (michi), which all human beings should follow piously. Moral codes do not change easily. Therefore, the Japanese took the existing pragmatic rules of international society in the late nineteenth century to be absolute and static, though they were not always fully convinced of their value.[7]

In its first few decades, the Gaimusho’s attention was overwhelmingly focused on Korea and China, where it found itself already in competition with the Japanese Army in establishing what amounted to Japan’s own form of colonial control.[8]

While the Gaimusho quickly developed thoughtful and comprehensive foreign policies towards Russia and the then-dominant global naval power, Great Britain, it was not until 1898 that it had any particular need to reckon with the United States as an emerging Pacific imperial rival. Exploding onto the world stage that year after having achieved a rapid victory against Spain, the United States not only annexed the Philippines from Spain in the subsequent peace settlement, but simultaneously acquired the Kingdom of Hawai’i, whose ruling monarch had once suggested to the Meiji Emperor a marriage between the Japanese crown prince and his own daughter, cleaving the islands to the Japanese Empire. [9]

(I told the story of King Kalakaua’s 1881 overture to Emperor Mutsuhito in this post)

In 1898, Japanese leaders on the whole believed that the Philippines were incapable of self-governance, that Japan was not in a position to acquire them itself, and that U.S. occupation of the Philippines was preferable to a German takeover. In fact, the Gaimusho conveyed to the British that Japan was too preoccupied dealing with Formosa to entertain designs on the Philippines, which may have further encouraged Britain to support U.S. acquisition. Moreover, when Filipino leader Emilio Aguinaldo then declared war on the U.S. occupying forces, Japan’s government “stood squarely behind the United States with respect to this additional phase of the Philippine problem.”[10]

Nonetheless, there were inevitable tensions and jealousies. In the free and diverse Japanese press of the era, one prominent journal opined, “It is assured that America will take the Philippines, and with Hawai’i and the Philippines, she will hold the key to the Pacific, and the balance of power will be completely upset. Japan bears no ill-will towards America, but she should prevent the Philippines from falling into the hands of this great nation.” Japan also was at that time hosting a number of exiled Asian revolutionaries, to whom it offered political asylum. Aguinaldo had emissaries in Tokyo who sought Japanese aid in their armed struggle against the United States, and they eventually made common cause with Sun Yat-sen, acquiring weapons with his assistance that had been salvaged from the Japanese Imperial Army. [11]

Japan’s new “America-whisperer”

Thus, the Gaimusho now needed diplomats who could offer Japan more insight about the United States and keep relations cordial. Twenty-five-year-old Hanihara was just the man for the job. His first posting was to the Japanese Embassy in Washington in 1901. He was not only fluent in English, he was also personable, frank and witty in a way that endeared him early on to the U.S. press corps, as became evident when he served as a junior member of the Japanese delegation to the 1905 Portsmouth Peace Conference in New Hampshire.

As the negotiations proceeded in strict confidence, the press corps plied Hanihara for any scrap of information, using any and all means at their disposal. They found him friendly enough but somewhat “like the Scot who treasures a secret not only for the secret’s sake, but for the congenial task of keeping it.”

Venting their frustration, toward the end of conference, the reporters decided to play a practical joke on the young diplomat. Hanihara, having finally freed himself from the press throng, returned to join his delegation at the conference. It was Viscount Komura, head of the Japanese delegation, who found a piece of paper pinned on the back of the unsuspecting junior diplomat. The note read: "This package is warranted to contain 90% alcohol." Great merriment ensued among the normally sedate and very sober group of Japanese delegates.[12]

In 1906 he was promoted to Second Secretary at the Embassy, where Japanese Ambassador Aoki Shūzo became so dependent upon him that he blocked Hanihara’s proposed transfer to London. For the duration of his unique diplomatic career, Hanihara remained almost exclusively devoted to Japan-U.S. relations.[13]

The “Gentleman’s Agreement”

By 1909, the year he was promoted to First Secretary, Hanihara was already painfully well aware that one of the largest sources of friction in U.S.-Japan relations, aside from Pacific imperialist and naval rivalries, was the issue of Japanese immigration, particularly in California. When the San Francisco Board of Education passed a resolution in 1906 segregating Japanese schoolchildren in violation of an 1894 U.S-Japan treaty, Ambassador Aoki, Hanihara, President Roosevelt, and Secretary of State Elihu Root held extensive discussions, eventually arriving at what became known as the “Gentleman’s Agreement” between 1907 and 1908 through several exchanges of diplomatic notes (As I noted two weeks ago, President Roosevelt separately, in his own inimitable fashion, publicly denounced San Francisco’s actions as a “wicked absurdity”). As I mentioned in this post:

Hanihara engaged in a multi-state fact-finding tour of the United States to study the Japanese immigrant community and conveyed his findings to the Gaimusho, where they remained buried for decades.

Japan and the United States were to follow up in 1911 (under the presidency of William H. Taft) with a bilateral Treaty of Commerce and Navigation providing, inter alia, that “the citizens or subjects of each of the high contracting parties shall have liberty to enter, travel, and reside in the territories of the other…”[14] The “Gentleman’s Agreement,” however, was an informal, face-saving arrangement,[15] whose text was never reported to Congress, pursuant to which Japan agreed to stop the emigration of unskilled laborers from Japan to the United States via an unstated policy of simply denying them passports. In March 1907, Roosevelt signed into law an additional statutory restriction on Japanese migrants entering the continental United States through Hawai’i, Mexico and Canada.[16] This, they all hoped, would silence the histrionics of the California exclusionists.

Up to this point in his career, Hanihara had worked with a succession of Republican administrations, to whom he was so beloved that he was typically addressed simply as “Hany,” including by President Taft. With the election in 1913 of Democratic presidential candidate Woodrow Wilson, he returned home for a short domestic assignment, during which time he got married. Lest he have any remaining gaps in his thorough understanding of the political dynamic around immigration issues in California, though, in 1916 (the year Wilson narrowly won re-election, defeating Republican nominee Charles Evans Hughes), Hanihara was appointed the Consul General in San Francisco, where he served until again returning to the Gaimusho’s home office in Tokyo in June 1918.[17]

Japan at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference

Woodrow Wilson’s January 8, 1918 speech, in which he set forth his country’s war objectives in a series of Fourteen Points, electrified the Japanese policy establishment. Since the mid-19th century, the Gaimusho had been laser-focused on mastering international relations as defined by European imperialist powers.[18] Now Wilson appeared to be articulating a radical new vision, based not on secret deals between great powers to carve up their colonial possessions, but on open governance by multilateral institutions—a League of Nations, for starters—and what he called “national self-determination.” Japan, having chosen to align itself with the Allies against Germany, was poised to participate in the 1919 Paris Peace Conference alongside the Big Four victorious nations, Britain, the United States, France and Italy, but its delegation needed to understand Wilson’s purportedly game-changing principles, for which the Gaimusho’s planning committee for the peace conference had been somewhat taken aback.[19] They now needed senior-level expertise on the United States in particular, which is why, at the age of 43, Hanihara was suddenly elevated by Prime Minister Hara Takashi to the position of Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs. Hanihara and a tight circle of other senior policy wonks known as the Oobei-Ha of the Gaimusho became known for progressive, internationalist thinking. They were the proponents of particularly strong relationships with Great Britain and the United States.[20]

Japan’s 20-member delegation to the Paris Conference, led by former Foreign Minister Makino Nobuaki, left Yokohama Harbor in December 1918 to much fanfare, a swelling of national pride, and with an ambitious plan to insert a general principle of racial equality into the draft covenant of the League of Nations.

While Japan would also seek recognition of its mandates over territories seized before or during the war—particularly the Shandong Peninsula it had wrested from Germany—the Racial Equality Bill, as it became known, was hugely popular with the Japanese public, the Japanese diplomatic corps, as well as the migrant Japanese communities overseas spread throughout the United States, Canada and Australia. There was no underlying agenda behind the proposal; rather, most of its proponents simply genuinely believed that "the abolition of discrimination based on racial differences is vital to the establishment of permanent world peace,"[21] a notion that would eventually be reflected in the United Nations’ Universal Declaration of Human Rights, but not until 1948.

The delegation was thus unprepared for the ferocity of the opposition to the proposal, particularly from the Australian contingent within the British delegation, who immediately viewed it as an attempt to legitimize large-scale Japanese immigration and hence a direct assault on its White Australia policy The Japanese repeatedly insisted that there was no motivation behind the bill to change member states’ immigration policies and legal restrictions, to no avail. Those who expected any sort of assistance or support from Woodrow Wilson were likely unaware of his own troubling record on race issues, which had included rollbacks of protections for African-Americans in the federal civil service and a screening in the White House of the Ku Klux Klan apologist film Birth of a Nation (because Hanihara was assigned to Tokyo during Wilson’s first term, he may well have missed some of these career highlights). [22]

The failure of the Racial Equality Bill would have a lasting impact on Japan, deepening an already existing split between those who embraced Anglo-American ideals and those who saw only hypocrisy. Makino, who prior to the Paris Conference had been known for his opposition to Japan’s aggressions in China, was blamed in the domestic press for his delegation’s disappointing results. A junior member of the delegation, Konoe Fumimaro, had written an opinion piece prior to the conference entitled “Reject the Anglo-American Centered Peace,” in which he argued that the Anglo-American rhetoric was entirely self-serving and sought merely to maintain the status quo under the guise of furthering humanity. His experience at the conference only served to confirm his sentiments, and when Konoe became Prime Minister in the late 1930s, his attitude was still that the Gaimusho was much too accommodating of the United States.[23]

Hanihara Becomes Japan’s Ambassador to the United States

Hanihara was not part of the Versailles delegation, however, and untainted by the conference results, his star continued to rise. As I described in this post,

shortly after the Washington Naval Disarmament Conference he succeeded Shidehara Kijuuroo as the Japanese Ambassador to the United States, holding a joint press conference in Hawai’i on his way to Washington with the outgoing U.S. Ambassador to Japan, Charles Warren, as their ships happened to arrive in Honolulu Harbor at the same time (Honolulu Harbor is about 8 miles from Pearl Harbor). In an interview with Outlook Magazine, the new ambassador observed that U.S.-Japan relations now seemed to be at an entirely new level of amity. When asked if any issues remained unresolved, however, he opined:

In my opinion at least one issue still remains. It is the treatment of Japanese nationals in the United States. This issue has nothing to do with the question of immigration. Japan no longer intends to send its own nationals as immigrants to the United States. For those Japanese who are already residents of the United States, however, we demand they receive treatment by the Americans equal to that of any other nationals in this country.[24]

The 1920 U.S. elections had resulted in the Republicans’ return to power, and Charles Evans Hughes, who had been selected as U.S. Secretary of State by President Warren G. Harding, was a dedicated internationalist himself who was to form a close working relationship with Hanihara. Unlike Harding, Hughes actually favored the United States joining the League of Nations. While the United States, unlike Japan, ultimately did not join, the United States can hardly be said to have withdrawn from the international scene; indeed, the Naval Disarmament Conference was a groundbreaking initiative and a solid foreign policy success for Hughes.

When Harding died in office in August 1923, Hughes stayed on as Secretary of State as Vice President Calvin Coolidge was elevated to the presidency. He worked closely with Hanihara during the debate over the Immigration Act.

“Picture brides” and alien land law controversies

The Japanese Embassy and Hughes’ State Department had in fact begun corresponding about California and Japanese immigrants as early as May 1922, prior to Hanihara’s arrival, when the Japanese Chargé d’Affaires in Washington inquired about a new U.S. Labor Department immigration regulation regarding “picture brides.” One of the many complaints the “California contingent” (whom I described in this post):

had about Japanese immigrants was that they were purportedly willfully flouting immigration law and the Gentleman’s Agreement by bringing in “picture brides” from Japan whom they had never met. In reality, this was simply a facet of the minimalist legal requirements for registering a marriage in Japan at that time, which did not require the lucky couple to be physically present, much less know one another particularly well.[25] Indeed, Hanihara’s wife was betrothed to him in similar fashion; her father, a director at Mitsui, simply informed her she was marrying a government official.[26] To the California contingent, however, the importation of “picture brides” was nothing less than an insidious attempt by Japan to gradually infiltrate and take over California through sheer force of numbers.

November 1923 then saw two U.S. Supreme Court decisions upholding California’s and Washington state’s alien land laws, about which Hanihara himself conveyed a detailed formal note to the State Department on December 4.[27] The U.S. Chargé in Tokyo was simultaneously reporting to Washington that

[s]ince publication of Supreme Court decision, agitation in Japanese press concerning Pacific Coast land question, while not violent, has been increasing and a number of Japanese associations interested in emigration have been publicly urging the Foreign Office that, “Owing to the now prevalent sympathy for Japan among American people, moment is opportune for suggesting to the American Government the appointment of a joint high commission to investigate whole matter.”[28]

Hanihara’s note to Hughes sought to cast no aspersions on the soundness of the Supreme Court’s reasoning but said the real problem was that

if the matter were to be left without recourse to some remedial measure other than judicial, it is feared that the so-called anti-Japanese element in the States where its activity has hitherto been permitted to develop freely, will find in the decisions of the highest tribunal of the country encouragement to devise still further means of persecution against Japanese, and it is not unlikely that the sinister influence of such a movement would soon be extended to other States. Events in the political and legislative history of the Pacific Coast and neighboring States in the past few years will furnish sufficient ground for such apprehension.[29]

Hanihara and Hughes engage on Johnson’s immigration bill

Hanihara was speaking from almost two decades of on-the-ground experience in the United States dealing with Californian anti-Japanese animus, and it took exactly one day for his prediction to come true. That day, December 5, 1923, Congressman Albert Johnson of Washington State introduced the first version of what would become the Immigration Act of 1924, H.R. 101, complete with a section 12(b) prohibiting immigration by any aliens ineligible for citizenship. By then, the Supreme Court had also ruled in Ozawa v. United States[30] that a Japanese person, being neither white nor of African descent, was ineligible for naturalized citizenship under the Naturalization Act. Section 12(b) was quite obviously targeted at Japanese immigrants. Hanihara met personally with Hughes on December 13, 1923, to discuss Johnson’s bill.[31]

Meanwhile, the U.S. Chargé in Tokyo was continuing to see domestic political agitation in Japan. Japan at that time was being led by Prime Minister Kato Tomosaburo (remember him, from the Naval Disarmament Conference?) and was at the height of what is now known as the “Taisho Democracy,” featuring multiple political parties in the Diet who, along with the free press, were not shy about criticizing the government.

The dominant party at the time was the Constitutional Association of Political Friendship, or the Rikken Seiyukai, which tended to have strong ties to rural areas and almost certainly would have been on the receiving end of complaints about the United States’ denial of land ownership rights to Japanese immigrant farmers.[32] Sometime in late December or early January 1924, a Seiyukai politician began demanding government action, to which the latter responded that it had already conveyed to the U.S. Government the “grave consequences” of the alien landownership dispute and was awaiting a reply from the latter.[33] Hanihara wrote again to the State Department on January 15, 1924, setting forth in writing his previous verbally-expressed concerns about the proposed Section 12(b) in Johnson’s immigration bill with remarkable directness for a diplomatic note:

To speak frankly, the mere fact, that such a provision is introduced in the proposed measure, in apparent disregard of these most friendly and effective endeavors on the part of the Japanese Government to meet the needs and wishes of the American Government and people, is mortifying enough to the Government and people of Japan. They are however exercising the utmost forbearance at this moment, and in so doing they confidently rely upon the high sense of justice and fair-play of the American Government and people, which, if properly approached, will readily understand why no such discriminatory provision as above-referred to should be allowed to become a part of the law of the land. [34]

This is how it came to be that Secretary Hughes sent a lengthy analysis to Congressman Johnson on his bill, dated February 8, 1924. Hughes was already an accomplished jurist; he would go on to become Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court in 1930, and one of the more well-regarded chief justices at that. His letter cited the 1911 treaty and noted that Section 12(b) would be “deeply resented by the Japanese people,” adding, “I believe such legislative action would largely undo the work of the Washington Conference on Limitation of Armament, which so greatly improved our relations with Japan.” He also asserted that, due to an “arrangement” with Japan (meaning the Gentleman’s Agreement), if Japan were simply subjected to the same quota system as all the European countries, there would be a total of only 246 Japanese immigrants entitled to enter the United States. [35]

Former Senator James D. Phelan had a response to Hughes, however, which Senator Kenneth McKellar (D-TN) arranged to have read into the Congressional Record on March 13.

(Remember Phelan? I last wrote about his meeting with the Hawai’i Sugar Plantation Association here—he had some pointed questions about Japanese contractors working at Pearl Harbor).

Phelan denied that the exclusion provision singled out the Japanese; rather, it was simply putting them on par with a wide variety of others ineligible for U.S. citizenship, including “the Chinese, the Hindoos, the Siamese, and other proud and cultured people.” The issue was not racial inferiority, he insisted, but racial differences

which are innate and which causes repugnance on both sides to intermarriage. Herbert Spencer, dwelling on the biological facts of science, warned both the Japanese and the Americans from ever commingling, excepting in friendly commercial relationship; that the result of the crossing of divergent races in exceedingly detrimental to both. And Japan is strong to-day because, following Herbert Spencer’s advice to her, they have maintained the purity of their race. They do not pretend that they even want to intermarry the whites, but they want to live in colonies which they have successfully established on the Pacific slope and increase and multiply.[36]

He additionally noted that Japan “excludes the Chinese and Koreans from Japan, although they are racially not very divergent, if at all.”

As far as the “Gentleman’s Agreement” was concerned, Phelan considered it “an experiment by which the Japanese themselves were given the privilege of determining who should come to the United States,” an experiment that had failed.

Thirty-eight thousand women, for instance, of Japanese birth have come into California since the gentleman’s agreement in 1908. These women are not only laborers, but are prolific wives who work almost uninterruptedly in the fields by the sides of their husbands. Of every 11 children born in California, 1 is now a Japanese, and in some parts of California, near Los Angeles and Sacramento, for instance, more than one-third of the births are Japanese.

The fact is that Japan is laying the foundation of a permanent colonization on the Pacific slope which will spread quickly to other parts of the West. It is apparent that the only way to check Japanese immigration is to impose an exclusion law such as we have against all other Asiatics. At present we have surrendered our sovereignty to Japan.[37]

Hanihara and Hughes, who were now in regular contact regarding the bill, met again on March 27. Phelan’s assertions about the growth of the Japanese population were simply inaccurate. According to statistics from the Commissioner General of Immigration within the U.S. Labor Department, the total net gain in the Japanese population between 1908 and 1923 had been no more than 8,681 Japanese, or an average of 578 per year, with a net decrease in 1920 after Japan had quietly addressed the phenomenon of the so-called “picture brides.”[38] Hughes confided to Hanihara that what disturbed him the most about the tenor of the Congressional debates was the way in which the Gentleman’s Agreement was being portrayed as a secret agreement designed to protect Japanese interests.

In response…Hughes floated an idea that he took pains to emphasize should not be considered as an official proposal. He suggested that Hanihara write a letter to him detailing the way in which the Gentlemen's Agreement had been reached. The letter would need to explain Japan's interpretation of the agreement, as well as Japan's successes in limiting emigration to the United States...[39]

Hanihara liked the idea. He had been a junior diplomat at the time the Gentleman’s Agreement was agreed to but had been a part of the negotiating team along with his trusted old friend, former Secretary of State Elihu Root. There was probably no one better qualified than Hanihara to set forth in writing what sort of arrangement had been reached through the exchange of diplomatic notes and what the arrangement meant to Japan. He obtained consent from the Gaimusho, and then set out to write the infamous “Hanihara Note” that would spell the end of his career, all over the inclusion of just two words in that note: grave consequences.

We’ll get to how that all played out. But first we need to talk about another Congressional contingent, who, like Fiorello La Guardia and his ilk, were much more preoccupied with European quotas than with Asian exclusion, but on the opposite side of the debate: the restrictionists. We’ll likely learn quite a bit more about people like Senator Kenneth McKellar of Tennessee and Congressman John Tillman of Arkansas, whose strong opposition to the influx of Southern and Eastern European immigrants (read: Italians and Jews) dovetailed with their strident support for another key federal government policy at that time: Prohibition.

[1] Congr. R. (House), April 11, 1924, pp. 6073-74.

[2] Read into the record at Congr. R. (Senate), April 8, 2024, at pp. 5810-13.

[3] Congr. R. (Senate), April 14, 1924, at p. 6305.

[4] Barbara J. Brooks, Japan’s Imperial Diplomacy: Consuls, Treaty Ports, and War in China, 1895-1938 (University of Hawai’i Press, 2000), at 16-17.

[5] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 65.

[6] Barbara J. Brooks, Japan’s Imperial Diplomacy: Consuls, Treaty Ports, and War in China, 1895-1938 (University of Hawai’i Press, 2000), at 42.

[7] Harumi Goto-Shibata, “Anti-Western Sentiments in Japanese Foreign Policy Debates, 1918-1922,” in Naoko Shimazu, ed., Nationalisms in Japan (Routledge, London and New York: 2006), at 68.

[8] Barbara J. Brooks, Japan’s Imperial Diplomacy: Consuls, Treaty Ports, and War in China, 1895-1938 (University of Hawai’i Press, 2000), at 81-82.

[9] Masaji Marumoto, “Vignette of Early Hawaii-Japan Relations: Highlights of King Kalakaua’s Sojourn in Japan on His Trip Around the World As Recorded in His Personal Diary,” Hawaiian Journal of History, Volume 10, 1976, available at https://evols.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/items/e5c0e6ba-bd72-42ac-858b-460c7a7ebb8b

(viewed April 8, 2025).

[10] James K. Eyre, “Japanese Imperialism and the Aguinaldo Insurrection,” United States Naval Institute Proceedings, Vol. 75/8/558 (August 1949), available at https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1949/august/japanese-imperialism-and-aguinaldo-insurrection (viewed June 19, 2025).

[11] James K. Eyre, “Japanese Imperialism and the Aguinaldo Insurrection,” United States Naval Institute Proceedings, Vol. 75/8/558 (August 1949), available at https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/1949/august/japanese-imperialism-and-aguinaldo-insurrection (viewed June 19, 2025).

[12] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 67.

[13] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 68.

[14] Quoted in Congr. R. (Senate), April 8, 1924, at 5811.

[15] These notes are reproduced in undated Memorandum by the Division of Far Eastern Affairs, Department of State, 711.945/1042, Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS), 1924, Vol. II, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1924v02/d279 (viewed June 23, 2025).

[16] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 70.

[17] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 82-87.

[18] See, e.g., Takashi Inoguchi, “The Wilsonian moment: Japan 1912-1922,” Japanese Journal of Political Science (2018), 19, pp. 565-570.

[19] Barbara J. Brooks, Japan’s Imperial Diplomacy: Consuls, Treaty Ports, and War in China, 1895-1938 (University of Hawai’i Press, 2000), at 29.

[20] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 89.

[21] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 11.

[22] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 10.

[23] Barbara J. Brooks, Japan’s Imperial Diplomacy: Consuls, Treaty Ports, and War in China, 1895-1938 (University of Hawai’i Press, 2000), at 31-32.

[24] Quoted in Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 126.

[25] Memorandum 711.94/310 of the Chief of the Division of Far Eastern Affairs of the Department of State, November 9, 1919, r.e. Decision of the Japanese Government to Discontinue Issuing Passports for “Picture Brides” to proceed to the United States, in Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS) 1919, Vol. II, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1919v02/pg_415 (viewed June 22, 2025).

[26] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 82-83.

[27] The Japanese Embassy to the U.S. Department of State, 811.5294/414, Substance of Instructions Received by the Japanese Ambassador from his Government, FRUS 1923, Vol. II, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1923v02/d392 (viewed June 23, 2025). The cases were Terrace et al v. Thompson, 263 U.S. 197, and Porterfield v. Webb, 263 U.S. 225.

[28] 811.5294/413: Telegram, The Chargé in Japan (Caffery) to the Secretary of State, Tokyo, December 5, 1923—2 p.m. [Received December 5—9:40 a.m.], in Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1923, Vol. II, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1923v02/d393 (viewed June 22, 2025).

[29] Id.

[30] 260 U.S. 178 (1922).

[31] As referenced in the Japanese Ambassador to the United States, 711.945/1063, January 15, 1924, FRUS, 1924, Volume II, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1924v02/d277 (viewed June 23, 2025).

[32] Richard Sims, Japanese Political History Since the Meiji Restoration (Palgrave, 2001), at 137.

[33] The Chargé (Caffery) in Japan to the Secretary of State, 811.5294/430, January 11, 1924 [received January 30], FRUS, 1924, Vol. II, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1924v02/d276 (viewed June 23, 2025).

[34] Memorandum, The Japanese Embassy to the Department of State, 711.945/1063, January 15, 1924, FRUS, 1924, Vol. II, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1924v02/d277 (viewed June 23, 2025).

[35] Text introduced in Cong. R.—Senate, April 8, 1924, at 5811-13.

[36] Congr. R.-Senate, March 13, 1924, at 4073 (entitled Japanese Exclusion (An answer to Secretary Hughes’s letter on the quota, by Hon. James D. Phelan).

[37] Id.

[38] The Secretary of State to President Coolidge, Washington, May 23, 1924, 150.01/886, in FRUS, 1924, Vol. II, available at https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1924v02/d299 (viewed June 23, 2025).

[39] Misuzu Hanihara Chow and Kiyofuku Chuma, The Turning Point in US-Japan Relations: Hanihara’s Cherry Blossom Diplomacy in 1920-1930 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2016), at 126.