Censorship and propaganda on the home front, 1917-1921

Information Warfare Part 2

This is Part 2 of my exploration of Open Source intelligence (OSINT), censorship and propaganda that I started last week.

This week I try to take full measure of how these interlocking activities played out on the home front.

Writing in 1835, Alexis de Toqueville observed that

“[i]n America there is scarcely a hamlet which has not its own newspaper. It may readily be imagined that neither discipline nor unity of design can be communicated to so multifarious a host, and each one is consequently led to fight under his own standard. All the political journals of the United States are indeed arrayed on the side of the administration or against it; but they attack and defend in a thousand different ways.”[1]

De Toqueville marvelled at the fact that there were no criminal penalties imposed on the press for “ an attack upon the existing laws, provided it be not attended with a violent infraction of them.” He found the volume of newspapers to “surpass belief,” and he attributed it to the fact that

“the Americans have established no central control over the expression of opinion, any more than over the conduct of business. These are circumstances which do not depend on human foresight; but it is owing to the laws of the Union that there are no licenses to be granted to printers, no securities demanded from editors as in France, and no stamp duty as in France and formerly in England. The consequence of this is that nothing is easier than to set up a newspaper, and a small number of readers suffices to defray the expenses of the editor.”[2]

What de Toqueville may not have appreciated was that there was a centralized control mechanism over the distribution of newspapers, if not their content, one that favored the economic viability of local newspapers and small-scale periodicals by conscious design. This was the U.S. Postal Service, enshrined in law by the Post Office Act of 1792, which not only provided explicitly for the use of the U.S. mail for all newspapers, but charged the nominal fee of one cent if the newspaper traveled fewer than one hundred miles and one and a half cents if a greater distance. By the 1820s, the wild proliferation of newspapers already made up between one-third and one-half of the total weight of the mail. “By underwriting the low-cost transmission of newspapers throughout the United States, the central government established a national market for information sixty years before a comparable national market would emerge for goods.”[3]

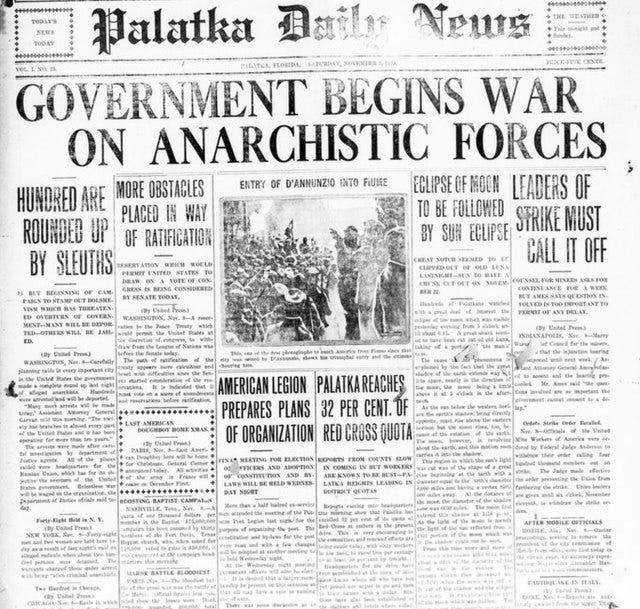

The first two laws passed by the U.S. Congress after the formal declaration of war against Germany in 1917 were the Selective Service Act of May 18, 1917, requiring all men ages 21 to 30 to register for the military draft;[4] and the Espionage Act of June 15, 1917, the latter of which provided for up to 20 years in jail for those who during wartime “willfully” caused or attempted to cause “insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny or refusal of duty” in the armed forces or “willfully” obstructed armed forces recruitment or enlistment.[5] By then the U.S. newspaper industry had changed substantially, with most mainstream daily newspapers no longer reliant on the mail; those were now mostly delivered to homes by carriers or sold at newsstands. These included several dailies or chains of dailies owned by politically influential individuals such as William Randolph Hearst, who continued to criticize the war effort with impunity. Smaller periodicals, however, were still heavily reliant on the U.S. Postal Service; this included most of the non-English-language newspapers, journals of opinions, and most significantly, the socialist press. The last of these was a particular bugaboo of President Wilson’s Postmaster General, Albert Sidney Burleson, a Southern Democrat and former Congressman who also treated with particular scorn “those offensive negro papers which constantly appeal to class and race prejudice.”[6]

It was Burleson who initiated the U.S. Government’s domestic OSINT collection efforts. Within a day of the enactment of the Espionage Act, Burleson directed local postmasters throughout the country to immediately send to him any publications “calculated to…cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny…or otherwise embarrass or hamper the Government in conducting the war.”[7] His first target was a tiny socialist newspaper in Hallettsville, Texas, called The Rebel, which in addition to opposing the war had recently exposed how Burleson had abused workers on a cotton plantation that his wife had inherited. Burleson promptly declared The Rebel “unmailable.”[8] Other publications of which individual issues were barred from the mail included The Public, for arguing that taxation rather than loans should fund most of the wartime spending; the Freeman’s Journal and Catholic Register, for quoting Thomas Jefferson on freedom for Ireland; and the Irish World, for predicting that, after the war, Palestine would be held as a colony of Great Britain on the same footing as Egypt.[9]

To enforce the Espionage Act, Burleson worked in tandem with Attorney General Gregory to bring criminal charges. In Philadelphia, the Executive Committee of the Socialist Party decided in August 1917 to print and mail 15,000 leaflets arguing that military conscription violated the 13th Amendment and should be resisted. The U.S. Government promptly executed a search warrant against the party’s premises and used the evidence seized to indict two of the committee members, Charles Schenck and Elizabeth Baer, for violation of the Espionage Act.[10] A similar fate befell the editors of a monthly magazine called The Masses, an early precursor to The New Yorker. At their trial, their star reporter John Reed testified about his firsthand experience covering the war in Flanders, where “the wounded had laid out there screaming and dying in the mud,” and one soldier had started shrieking so uncontrollably that his fellow soldiers gagged him and took him to the base hospital. The title of his article upon return to New York, where he found women’s charity groups knitting socks for soldiers, was “Knit a Straight Jacket for Your Soldier Boy.” The jury acquitted the editors, but Burleson revoked the magazine’s second class mailing permit entirely, effectively putting it out of business.[11]

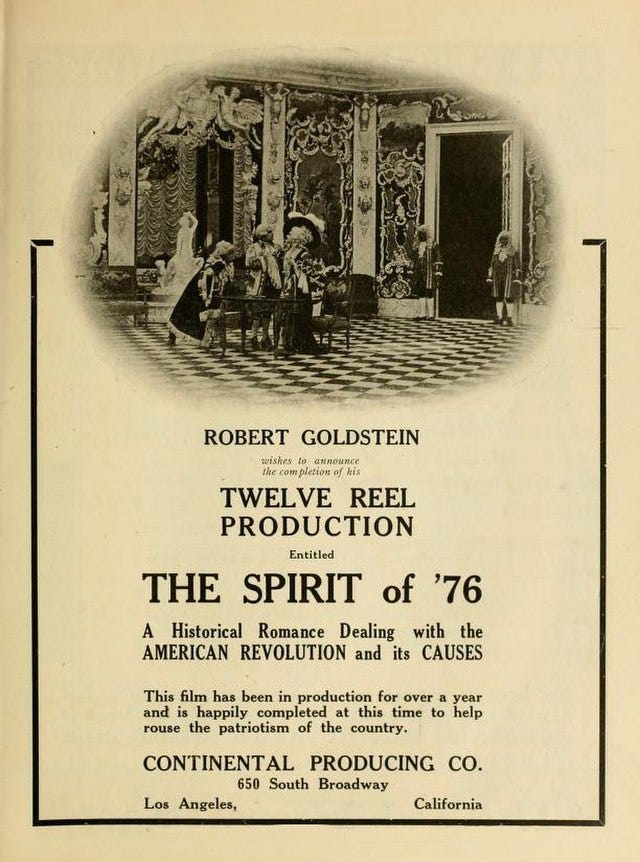

The Espionage Act empowered the government to extend censorship to motion pictures as well. In Los Angeles, Robert Goldstein, a native Californian of German-Jewish descent who had worked on D.W. Griffith’s Ku Klux Klan apologia film Birth of a Nation, had been working on his own silent film on the American Revolution, called the Spirit of ’76, since around 1915. The film revolved around a fictitious affair between King George III and a common Quaker woman and featured scenes of brutality on the part of British troops, including bayoneting a baby. The film premiered in Chicago, after which Goldstein was told by Chicago’s Police Censor Board to remove several scenes. He complied in Chicago but showed the uncensored version at the Los Angeles premiere a few months later, at which point he was indicted under the federal Espionage Act.

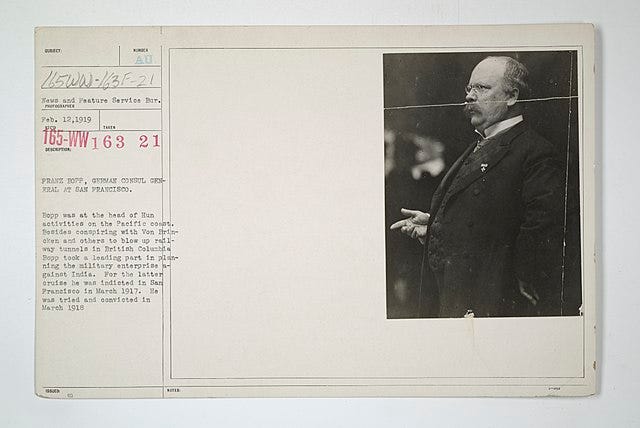

During the trial, a witness for the prosecution testified that Franz Bopp, the former German consul, had discussed financing the production of the film with Goldstein, who had said that the film would appeal to German Turnverein members throughout the United States; furthermore, the witness had said Goldstein was “very bitter towards all Englishmen.”[12]

Unable to assert his First Amendment rights, as the Supreme Court had ruled in 1915 that the First Amendment did not apply to motion pictures,[13] Goldstein could only offer the defense that the soldier depicted bayoneting a baby was, in fact, a Hessian mercenary hired by the British. He was sentenced to a fine of $5,000 and ten years in prison, the judge observing that Goldstein’s intent “had been to arouse enmity against our ally, Great Britain, by seeking to prove that, 100 years ago, that same nation had been guilty of the same class of atrocities as are now charged against the detestible Huns.”[14]

But censorship was only half of the information war that Woodrow Wilson intended to wage on his restless domestic population. Propaganda was the other half. On April 14, 1917, Wilson issued Executive Order 2594, establishing the Committee on Public Information (CPI), consisting of the Secretaries of State, War and the Navy, and appointing journalist George Creel as its chairman.[15]

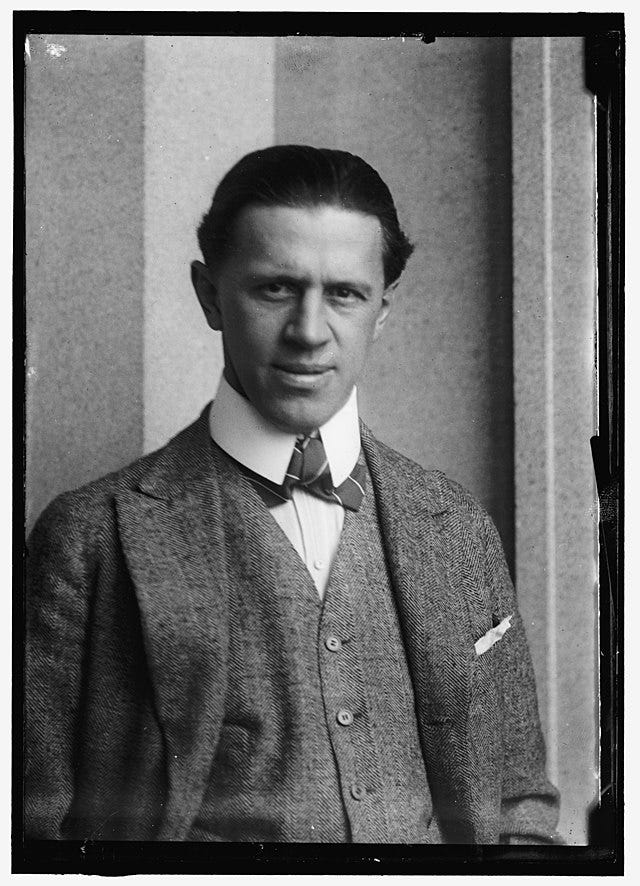

Creel recruited a number of talented journalists, advertisers, academics and artists, including Edward Bernays, who headed the CPI’s Foreign Section and is known today as “the father of Public Affairs.”[16]

Creel aimed at nothing less than the shaping of public opinion through a multi-layered effort that included, by war’s end,

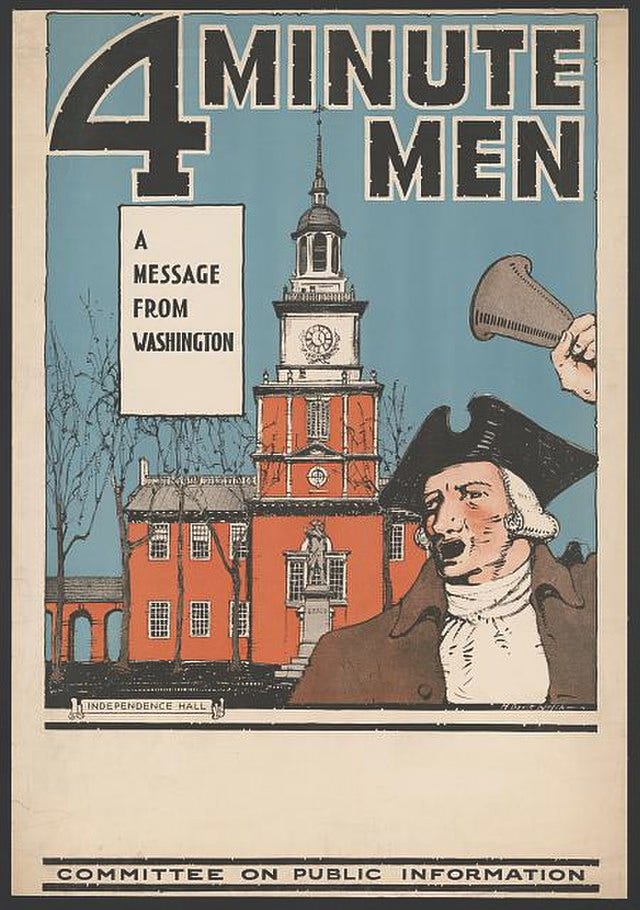

“More than six thousand separate and distinct news releases…some half-hundred separate and distinct pamphlets, brimmed with detail; seventy-five thousand Four Minute Men speaking nightly; other hundreds delivering more extended addresses regularly; thousands of advertisements; countless motion and still pictures, postcards and painted signs; war expositions; intimate contacts with twenty-three foreign language groups; the Official Bulletin, appearing daily for two years; and in every capital of the world, outside the Central Powers, offices and representatives, served by daily cable and mail services…”[17]

Initially, Creel set out to simply coordinate the issuance of official U.S. government news bulletins regarding the war, such as the July 3, 1917, news release from the Navy announcing the safe arrival of the last contingent of the AEF on French shores, having successfully fought off several German U-boat attacks en route. When reporters and Republican members of Congress immediately began questioning whether the U-boat attacks had actually occurred, as well as the general “bombast” or “flamboyancy” of the news release, Creel coordinated the release of other reports purportedly backing up the U.S. Navy’s account.[18] He certainly believed that what he was doing was not censorship and not “disinformation” but rather, combatting the disinformation promoted by others, including the Central Powers, and providing accurate information about events like troop movements in a manner that preserved operational security (i.e., after the movement had been safely completed).

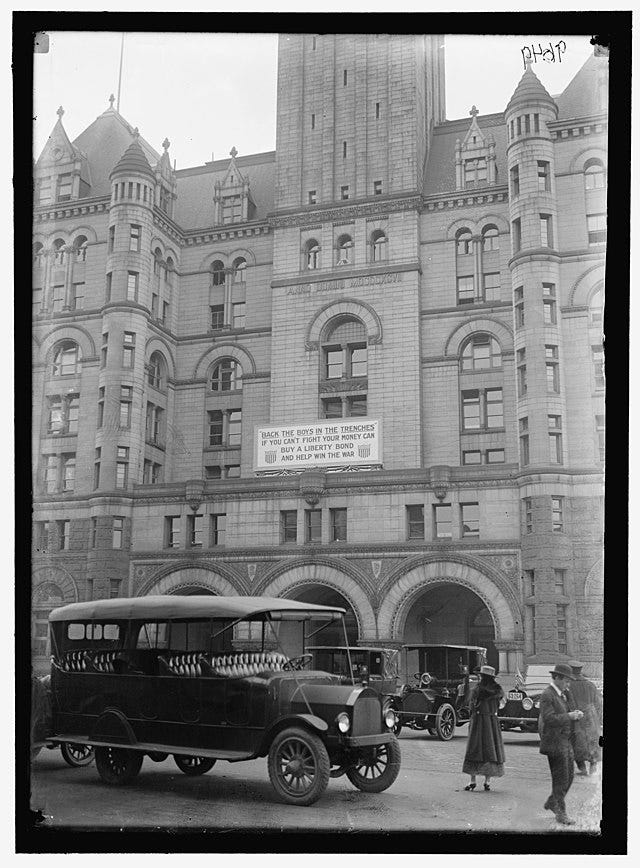

Nonetheless, his purpose writ large was to “sell” or “advertise” the Wilson Administration’s war effort and everything needed to support it, including the purchase of Liberty War Bonds. The “Four Minute Men” were recruited among local, trusted public figures (mostly men, but some women, including the actress Mary Pickford) to speak personally to motion picture audiences about the importance of supporting the war effort, using talking points prepared for them by the CPI, during the four minutes that it typically took for the theater projectionist to change reels. Special “Junior Four Minute Men Bulletins” were distributed to educators for use with school children. [19] The journalist Mark Sullivan later observed that “it became difficult for half a dozen persons to come together without having a Four Minute Man descend upon them.”[20] How far some of them may have strayed from the talking points over millions of public addresses is anyone’s guess.

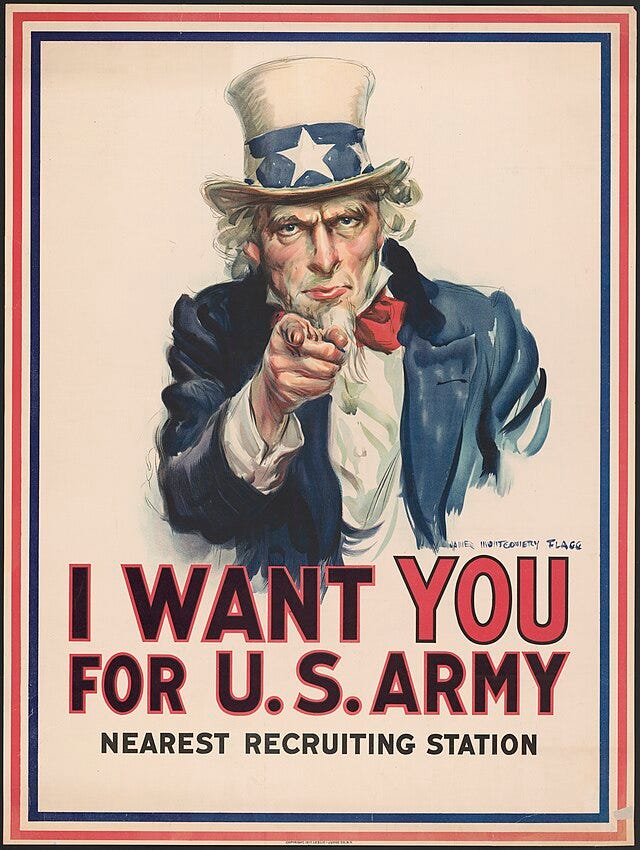

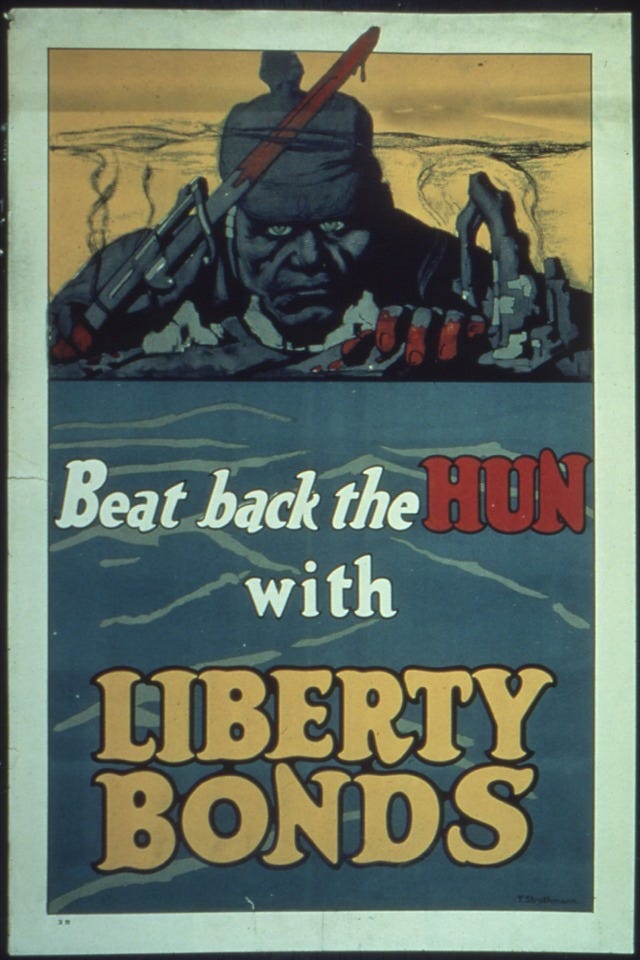

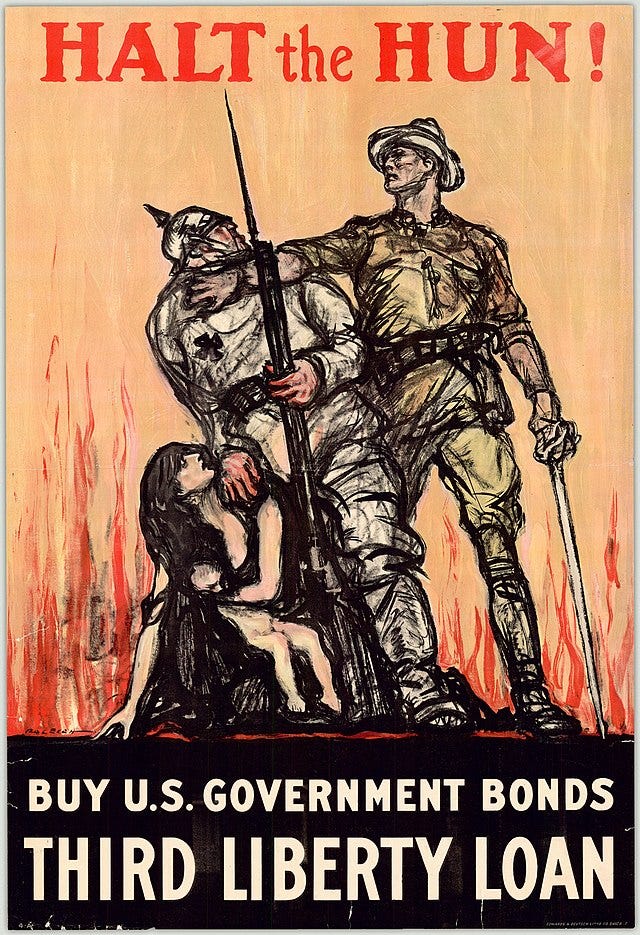

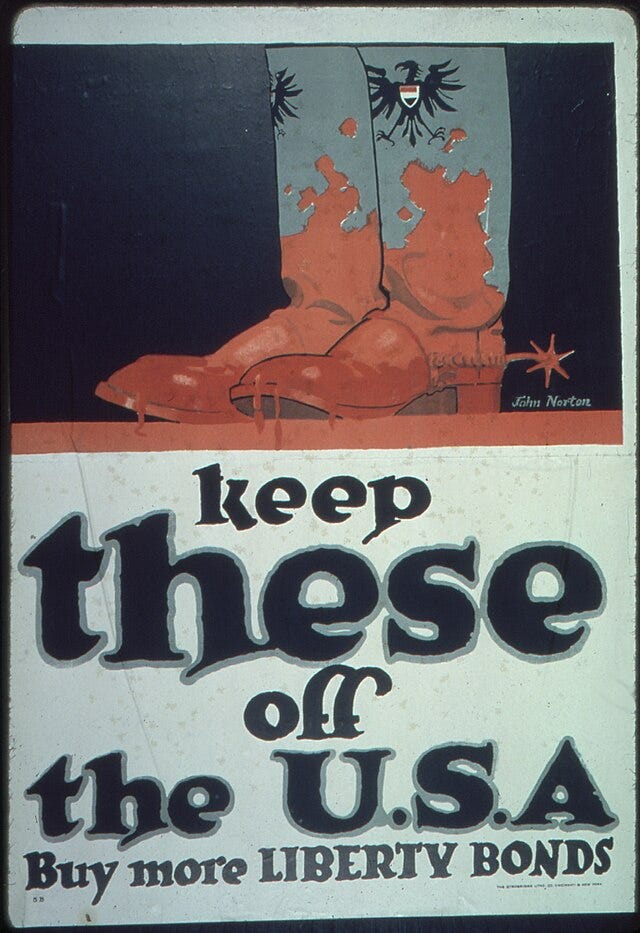

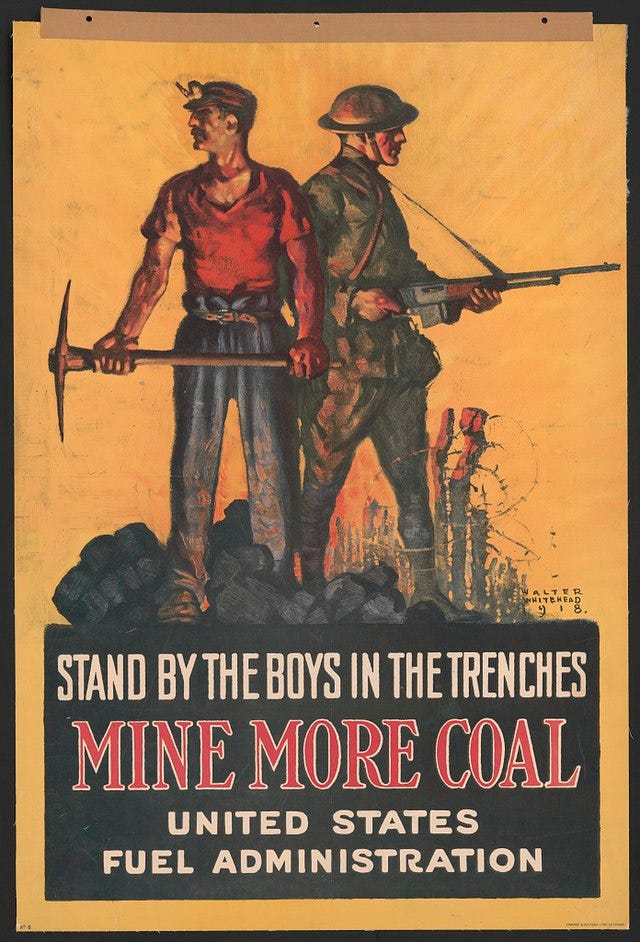

The CPI’s Division of Pictorial Publicity employed visual artists to design posters, “powerful imagery designed to boost enlistments, demonize the enemy, sell war bonds, and galvanize the home front.”[21] Some of these posters are now iconic, such as the Uncle Sam “I want you!” recruitment poster for the U.S. Army.

Several of the artists, however, drew upon earlier British and French examples that emphasized the brutality of German soldiers towards the Belgians, portraying them as uncivilized beasts attacking white women, and also suggesting that they posed a threat to the home front. The CPI had a Syndicate Features Division that employed fiction writers, one of whom, Stanford professor John S. P. Tatlock, published a fantastical story about a German invasion of the American mainland, “complete with gory scenes of murder, arson, and rape.”[22]

What Creel perhaps did not account for is how such dehumanizing propaganda, set against a backdrop of pre-1917 British propaganda about the pervasiveness of German spies operating in the United States, (see my previous post):

would reverberate among white Americans who already had a certain baseline of fear regarding domestic Mexican-American and Black American populations. By the time of U.S. entry into the war, which was deeply influenced by the British release of the Zimmermann telegram, Americans were already primed to believe that Mexicans were conspiring with Germany to take back the territories the United States had acquired in the Mexican-American War. White Americans also believed—not wholly without foundation (see my previous post):

—that German agents were trying to foment racial discord among Blacks.

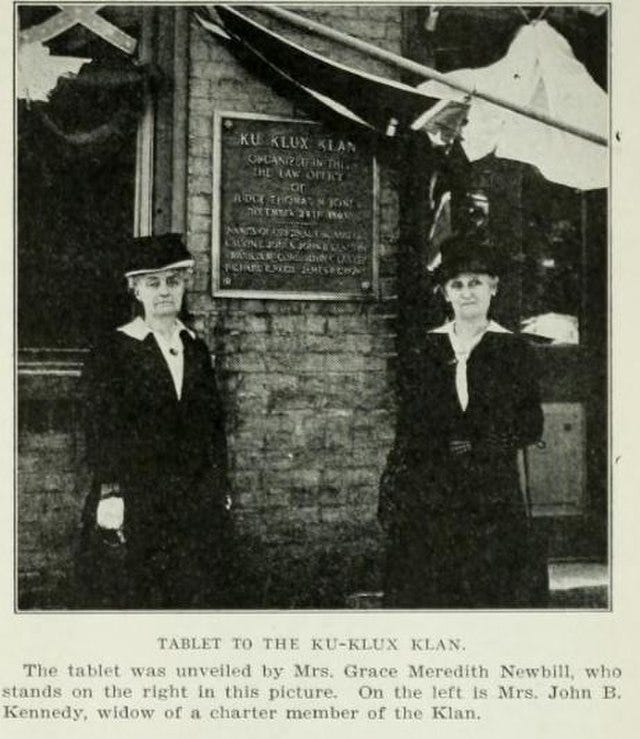

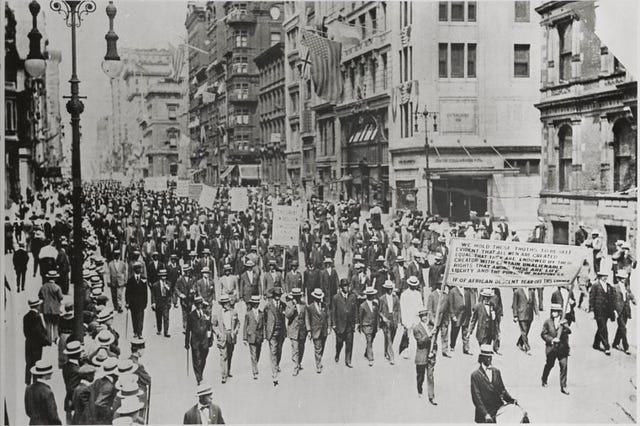

Where white Americans’ imagination ran away with them was on the susceptibility of these minority populations to German intrigue. To predict an enemy’s behavior requires knowledge of both its intent and its capabilities. The fact that German intelligence agents intended to foment racial uprisings in the United States did not mean they were actually capable of succeeding. But the U.S. press immediately ran a flurry of news articles under such headlines as “German Agents Busy Trying to Incite Negroes Against Government in Tobacco and Cotton Belt” (Richmond-Times Dispatch, April 5, 1917), “Say Spies Inciting Negroes to Revolt” (Boston Daily Globe, April 5, 1917); “Germans Plot Negro Uprising in South” (New York Tribune, April 4, 1917); and “South is Troubled by German Agents” (Atlanta Constitution, April 5, 1917).[23] These stories immediately prompted discussion among white Southerners about the necessity of revivifying the Ku Klux Klan, with one assuring the New York Tribune that the “citizens of Greensboro [North Carolina] are laying their plans against the black menace.”[24]

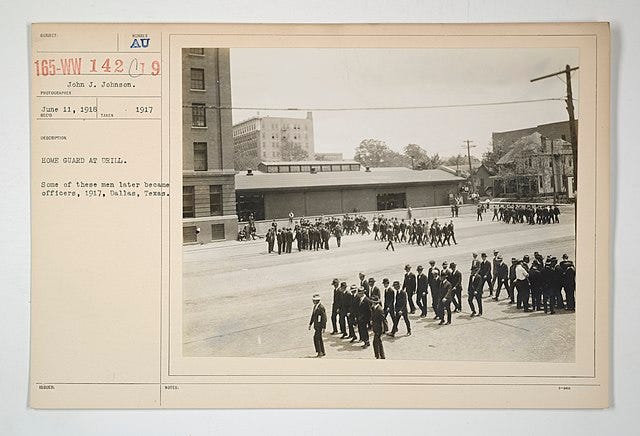

W.E.B. DuBois saw through the ruse, observing in May 1917, “Any tale or propaganda by which the Bourbon South can get the country to believe the Negro is a menace would play straight into the hands of the slaveholders. Martial law would be declared in the South and this is what the reactionaries want: to stop migration [of Blacks to northern cities].”[25] But the CPI itself believed the Southern white rumor mongering, issuing a bulletin in 1918 citing the danger of German propaganda circulating “among the negroes, taking advantage of their illiteracy and consequent credulity.”[26] White southern men, some of them veterans of the Spanish-American War or even the Civil War, now too old to serve overseas, wrote to state and federal officials begging for assistance in forming “home guards” against the African-American and Mexican-American threat. In June 1917, Congress made such home guards eligible to receive rifles, ammunition and other military supplies from the federal government. White lynchers killed a total of 38 Blacks in 1917, 58 in 1918, and more than 70 in 1919.[27]

Black newspapers and thought leaders, including DuBois, were put in a bind: On the one hand, they needed to profess their loyalty to the United States and their willingness to serve in the military, sometimes emphatically and repeatedly, in order to counter the insinuations that they were plotting an uprising instigated by the Germans. On the other hand, they needed to report the lynchings, the segregation, the mistreatment of those who did join the Army, in an effort to explain to white Americans, and the U.S. Government in particular, the conditions that were testing the bounds of their loyalty.

As discussed in my previous post,

Joel Spingarn, the national chairman of the NAACP; and Walter Loving, who had served in the Philippines, decided to work with Ralph Van Deman in the Military Intelligence Division, using their positions to try to create opportunities for Black military officers and combat racism in the movies and the press.[28] By May 1918, Loving instead found himself in the position of being sent as Van Deman’s emissary to the Chicago Defender, a Black newspaper known for its exposés of lynching, to warn the editor that “repeated attacks on the Government…will tend to create…a feeling of disloyalty among the negroes,” and that the editor “would be held strictly responsible and accountable for any [such] article.” Afterwards, the Defender continued reporting lynching and discrimination, but alongside frequent expressions of patriotism. The editor also pledged to buy Liberty Bonds with money that had been set aside for a new press and office building.[29]

As the CPI’s propaganda shifted from a more strictly focused criticism of the regime in Germany to Germans generally, xenophobic sentiment came to be directed at German-Americans, and censorship efforts on the foreign language press. Creel, who regularly pushed for CPI’s materials to be published in the foreign language press, believed there were 865 such newspapers in the United States, 745 of which published regularly.[30] The October 1917 Trading with the Enemy Act rendered it unlawful to publish any news article in a foreign language “respecting the Government of the United States, or of any nation engaged in the present war, its policies, international relations, the state or conduct of the war, or any matter relating thereto,” unless such publisher first filed with the local postmaster “a true and complete translation of the entire article.”[31] To enforce these restrictions, Wilson created a Censorship Board that included the Secretaries of War and the Navy, Postmaster General Burleson, the War Trade Board, and Creel.[32]

Under these conditions, foreign language newspapers simply started going out of business. Between 1917 and 1920, the number of German-language publications decreased from 522 to 228.[33] The new restrictions affected not only the German language press, but the foreign language newsletters of the wide variety of Eastern European ethnic groups still under the nominal rule of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, on which the United States declared war in December 1917, rendering all of their nationals “enemy aliens.”[34]

The unrelenting peer pressure to purchase Liberty Bonds, coupled with the xenophobia that already existed towards Eastern European immigrants, eventually manifested itself as vigilante violence and then tragedy. When an Austro-Hungarian national named Joseph Kovath, who worked in a steel mill in Johnstown, Pennsylvania, refused to buy the bonds, about 40-50 factory workers soaked him in a “concrete bed,” then smeared him with grease and dragged him bound through the streets. After he purchased a $100 war bond (the modern equivalent of about $2000), he was allowed to return to work.[35]

German immigrant Robert Paul Prager was less fortunate. After trying to join the U.S. Navy upon U.S. entry into the war and being rejected because he had a glass eye, he moved to southern Illinois to work in the coal mines. Even though he was not a member of the United Mine Workers of America, the union allowed him to work in a mine in Maryville until his application could be acted upon. At the time, rumors were already circulating that a German agent had stolen dynamite from the Maryville mine. After Prager reportedly asked what the effects would be of an explosion in the mine, the local union rejected his application, and a group of miners told him to leave town, personally escorting him to nearby Collinsville the night of April 3, 1918.

The Collinsville police refused to place him under arrest, so he returned to his home in Maryville and wrote an angry statement directed at the local union, of which he posted a dozen copies around town, insisting that he was a loyal American working man and was being unfairly denied a right to make a living. That night, a mob seized him from his home, walked him barefoot down the street draped in an American flag, and then lynched him from a tree outside the city limits in front of 200 spectators. Eleven men were later tried for murder, defending themselves by citing an unwritten law allowing “patriotic murder” in times of danger. They were all acquitted by a jury that deliberated 45 minutes before rendering its verdict.[36]

To Washington policymakers, the cause of such violent vigilantism was obvious—the censorship laws were still too lax. Certainly, this was the underlying cause cited by the mayor of Collinsville for the lynching (over which, he pointed out, he had had no control, since it occurred outside city limits): it had been “the direct result of a widespread feeling in this community that the Government will not punish disloyalty.” Indeed, the mayor himself had repeatedly reported instances of disloyalty to federal authorities, but nothing had happened because of the inadequacies of the law.[37] The U.S. Senate Judiciary responded with a bill amending the Espionage Act, which led to a series of amendments that were enacted on May 16, 1918, before Prager’s murderers had even been put on trial. These amendments are known today as the Sedition Act.

Amended by the Sedition Act, Section 3 of the Espionage Act now provided, inter alia, that “whoever, when the United States is at war, shall willfully utter, print, write, or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States…shall be punished by a fine of not more than $10,000 or imprisonment for not more than twenty years, or both…”[38] This particular provision tracked virtually verbatim Act No. 292 enacted November 4, 1901, by the Philippines Commission[39] and presumably was intended to have a similar effect on freedom of the press in the United States that it had had in the Philippines (which I discussed here):

Unlike the rest of the Espionage Act, which remains in effect, the Sedition Act was repealed in late 1920.

At the time of the passage of the Sedition Act, American newspapers were running a series of boldface headlines reporting negative developments (e.g., “Teutons Are Still Gaining Ground”; “French Are Completely Surrounded by Enemy,” etc.). The reason the newspapers were reporting that the war was not going well was that the war was not going well. Following the Bolshevik takeover of Russia in November 1917, Russia had formally withdrawn from the war against Germany in the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on March 3, 1918. This freed up German troops on the Eastern Front for redeployment on the Western Front, and the Germans had quickly launched a major offensive on March 21, 1918, pushing the Allies back. A new long-range artillery gun deployed by the Germans could now land shells inside Paris.[40]

But the threat of “Bolshevism” was also in and of itself now considered a threat to the U.S. home front, as the Russian Revolution was providing inspiration to a variety of soldiers and factory workers across the globe who no longer felt like following orders. Sailors on a Russian freighter that stopped to refuel in Seattle, a stronghold for the International Workers of the World (IWW) or the “Wobblies,” were startled to find themselves cheered as heroes.[41]

In March 1918, Creel asked the Censorship Board chairman, Chief Postal Censor Robert L. Maddox, to have censors keep a watch out for material published by the Bolsheviks and to try to prevent it from entering the country.[42] Meanwhile, a new section 4 added to the Espionage Act by the Sedition Act gave Postmaster General Burleson explicit legal authority to do what he had already been doing with relish which was to return to its original sender any mail that he determined was in violation of the Espionage Act, with the words “Mail to this address undeliverable under Espionage Act” stamped on the envelope.[43]

This provided the U.S. Government with yet another weapon in the war against the Wobblies (which I discussed here:)

The 166 Wobblies who had been arrested in September 1917 in Chicago and were facing trial in April 1918 were being supported by a committee that was soliciting donations to help support the defendants’ wives and children. The committee now found that checks were no longer arriving in the mail. The defendants’ counsel also could not have their mail delivered while seeking witnesses for the defense.[44] A socialist newspaper in Milwaukee discovered that it was no longer receiving business correspondence, nor even their mailed subscriptions to the New York Times and the Chicago Tribune. Instead, envelopes were being returned to the senders, marked “Undeliverable under the Espionage Act.”[45]

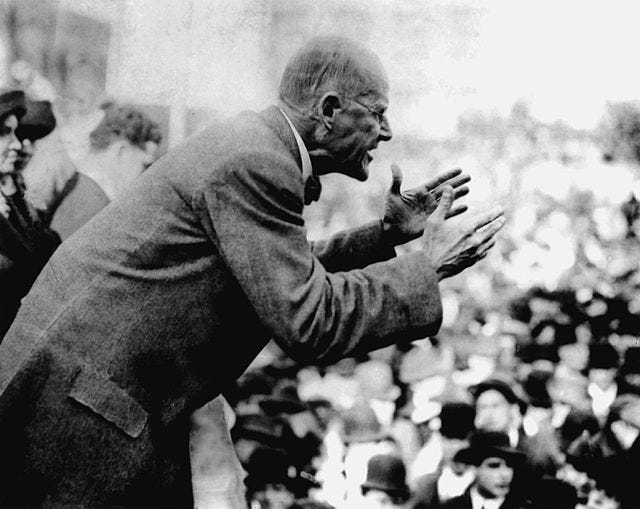

Then, on June 16, 1918, 62-year-old IWW co-founder and longtime Socialist presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs gave a barn-burner of a speech at the Ohio State Socialist Party Convention. While he railed against German imperialism, he also declared that “our hearts are with the Bolsheviki of Russia,” and “[f]rom the crown of my head to the soles of my feet I am a Bolshevik and proud of it.” He then said what would later be interpreted as urging people to resist the draft: “You need at this time especially to know that you are fit for something better than slavery and cannon fodder.”[46]

In the audience, stenographers employed by U.S. Attorney E.S. Wertz of the Northern District of Ohio were taking notes. While Attorney General Gregory would express some reservations about prosecuting such a prominent public figure, Wertz successfully obtained an indictment charging Debs with ten counts of violations of the newly amended Espionage Act. Debs was convicted by a jury on three of those counts and sentenced to ten years in prison.[47]

In July 1918, President Wilson made a decision to send two contingents of 7,000 men into Siberia, not to overthrow the Russian Bolsheviks, but simply to provide them a screen so that several divisions of Czech fighters in the region who were still loyal to the Entente could withdraw to Vladivostok and eventually make their way to the Western Front (the U.S. troops ended up staying in Siberia until 1920 in a largely pointless occupation).[48]

In response, Jacob Abrams and a group of four other Russian immigrants in New York City immediately decided to print up five thousand pamphlets in English and Yiddish, asserting that Wilson’s “shameful, cowardly silence about the intervention in Russia reveals the hypocrisy of the plutocratic gang in Washington and vicinity” and that the workers of the world “must now throw away all confidence, must spit in the face the false, hypocritic, military propaganda which has fooled you so relentlessly, calling forth your sympathy, your help, to the prosecution of the war.”[49] They distributed the pamphlets around town, with one of the five deciding on August 22, 1918, to throw a large number of them out the window of the garment factory where he worked, sending them fluttering down to passers-by on the streets of Manhattan.

These five were also promptly tried and convicted under the amended Espionage Act, a conviction they eventually appealed to the Supreme Court, except for one defendant who died during the trial from pneumonia, his heart condition worsened by a severe beating he experienced at the hands of New York police. [50] In total, over 1000 men and women were convicted under the Espionage and Sedition Acts between 1917 and 1918, with untold additional individuals convicted under state or municipal sedition laws.[51]

The November 1918 Armistice brought little abatement to the censorship and repression, as authorities gradually shifted focus from the German to the Bolshevik menace. Wilson did disband the CPI by Executive Order 3154 on August 21, 1919. Before Wilson left for Paris to attend the Versailles Conference, he also gently suggested to Postmaster General Burleson that censorship was “no longer performing a necessary function” and that “I hope that you agree with me.” Burleson, however, apparently did not agree and blithely continued his campaign against left-wing periodicals for another two years.[52] When Seattle experienced a widespread, general strike on February 6, 1919, amid soaring national inflation, authorities once again raided the local offices of the Socialist Party and the IWW.[53] Meanwhile, the U.S. Supreme Court was repeatedly affirming the convictions that had been obtained under the Espionage Act: Charles Schenck and Elizabeth Baer on March 3, 1919; Eugene Debs on March 10, 1919; Jacob Abrams and his comrades on November 10, 1919.[54]

The Senate Judiciary Committee established a special subcommittee headed by North Carolina Democrat Lee Overman, which between September 1918 and June 1919 investigated both pro-German and Bolshevik elements in the United States.

The Seattle strike particularly energized the subcommittee, which concluded in its final report that instituting Bolshevism in the United States would result in "the repudiation of democracy and the establishment of a dictatorship,” “the confiscation of all land…factories, mills, mines and industrial institutions” as well as churches and all church property, the “conferring of the rights of citizenship on aliens without regard to length of residence or intelligence,” and “the opening of the doors of all prisons and penitentiaries.”[55]

In early 1919, Attorney General Gregory stepped down, “to the great relief of progressives,” and was replaced by former Pennsylvania congressman A. Mitchell Palmer, who convinced Wilson to grant clemency to more than one hundred people who were serving Espionage Act sentences.[56] But on the night of June 2, 1919, Palmer was one of a number of high-ranking officials whose homes were targeted by a well-coordinated attack involving pipe bombs. While Palmer and his family were luckily unharmed, the attack, which destroyed the entire façade of his house, left him “profoundly transformed.” The perpetrators were never found, but Palmer found great political advantage in attacking the Wobblies and the Socialists, along with all the other usual suspects.[57] Following a summer of race riots across the country, most of them instigated by whites, by November, Palmer was reporting to the U.S. Senate that “[a]t this time, there can no longer be any question of a well-concerted movement among a certain class of Negro leaders of thought and action to constitute themselves a determined and persistent source of radical opposition to the Government, and to the established rule of law and order…The Negro is ‘seeing red.’”[58]

It was not until there was political and legal backlash to Palmer’s large-scale anti-immigrant raids in 1920 that the country’s “red fever” finally broke. With their strong, anti-Communist and anti-immigrant stance, both Palmer and General Leonard Wood, seeking their two parties’ respective presidential nominations that year, suddenly found themselves out of step with the national mood.[59] Instead, the presidential race in 1920 was waged between Democratic Governor James Cox of Ohio and Republican Senator Warren G. Harding, also from Ohio. Senator Harding had come under fire in June 1917 for a Memorial Day speech in which he criticized the Liberty Bond sales campaign as “hysterical and unseemly.”[60] Harding, a former newspaper editor, prevailed in the presidential race, and as President, he replaced Postmaster Burleson in 1922 with Hubert Work, who ceased the postal service’s press censorship activities. Congress repealed the Sedition Act on December 13, 1920.

Harding also began slowly freeing a total of 147 federal prisoners convicted during the war whose sentences had not yet been commuted by Wilson following the repeal of the Sedition Act. Wilson had refused to commute the sentence of Eugene Debs, who had still, while incarcerated, managed to win more than 900,000 votes in the presidential race as the Socialist Party candidate.[61] Harding not only freed Debs in time to let him spend Christmas with his family, he invited him to a one-on-one meeting at the White House on December 26, 1921. When shown into the President’s office, Debs was startled to see Harding “bounding out of his chair,” exclaiming, “Well, I have heard so damned much about you, Mr. Debs, that I am now very glad to meet you personally!”[62] Debs was happy to be free, but as he received a commutation of sentence and not a pardon, he did not regain the right to vote, nor did he have much of a viable third party to represent, the Socialist Party having been thoroughly decimated by wartime repression.

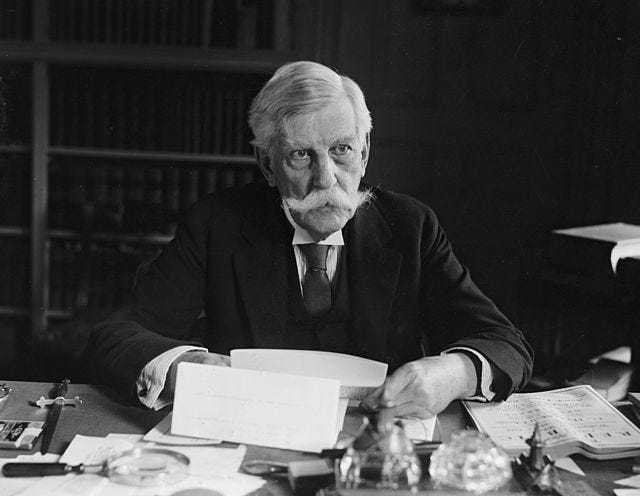

As for the Supreme Court jurisprudence, its case law on the Sedition Act and its First Amendment implications would not be revisited for a very long time. Much of the new conceptualization of the First Amendment during World War I was being carried out in, of all places, the War Department, where War Secretary Newton Baker became heavily reliant on his special assistant, Austrian-born Harvard Law professor Felix Frankfurter, to implement reasonable policies dealing with conscientious objectors to military service.[63]

But sometimes dissents to Supreme Court opinions take on a life of their own. A dissent filed by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes in Abrams v. United States—the case involving the Russian Jewish immigrants throwing pamphlets out the window protesting the U.S. intervention in Siberia—came as a surprise to many of Holmes’ colleagues. Holmes convinced his fellow justice Louis Brandeis to join in his dissent, which has since come to stand for in many ways the current interpretation of First Amendment rights, including the contours of what has become known as the “clear and present danger” test. Here is what Holmes said in his dissent:

“I never have seen any reason to doubt that the questions of law that alone were before this Court in the cases of Schenck, Frohwerk and Debs, 249 U. S. 249 U.S. 47, 249 U. S. 204, 249 U. S. 211, were rightly decided. I do not doubt for a moment that, by the same reasoning that would justify punishing persuasion to murder, the United States constitutionally may punish speech that produces or is intended to produce a clear and imminent danger that it will bring about forthwith certain substantive evils that the United States constitutionally may seek to prevent. The power undoubtedly is greater in time of war than in time of peace, because war opens dangers that do not exist at other times.

“But, as against dangers peculiar to war, as against others, the principle of the right to free speech is always the same. It is only the present danger of immediate evil or an intent to bring it about that warrants Congress in setting a limit to the expression of opinion where private rights are not concerned. Congress certainly cannot forbid all effort to change the mind of the country. Now nobody can suppose that the surreptitious publishing of a silly leaflet by an unknown man, without more, would present any immediate danger that its opinions would hinder the success of the government arms or have any appreciable tendency to do so…

“In this case, sentences of twenty years' imprisonment have been imposed for the publishing of two leaflets that I believe the defendants had as much right to publish as the Government has to publish the Constitution of the United States now vainly invoked by them….

“[W]hen men have realized that time has upset many fighting faiths, they may come to believe even more than they believe the very foundations of their own conduct that the ultimate good desired is better reached by free trade in ideas -- that the best test of truth is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the competition of the market, and that truth is the only ground upon which their wishes safely can be carried out.

“That, at any rate, is the theory of our Constitution. It is an experiment, as all life is an experiment. Every year, if not every day, we have to wager our salvation upon some prophecy based upon imperfect knowledge. While that experiment is part of our system, I think that we should be eternally vigilant against attempts to check the expression of opinions that we loathe…

“Only the emergency that makes it immediately dangerous to leave the correction of evil counsels to time warrants making any exception to the sweeping command, ‘Congress shall make no law . . . abridging the freedom of speech’…I regret that I cannot put into more impressive words my belief that, in their conviction upon this indictment, the defendants were deprived of their rights under the Constitution of the United States.”[64]

This passage has been described by a Holmes biographer as one of the “most-quoted justifications for freedom of expression in the English-speaking world.”[65]

[1] Alexis de Toqueville, Democracy in America, Chapter XI Liberty of the Press in the United States (London: Saunders and Oatley, 1835), available at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/815/815-h/815-h.htm#link2HCH0026 (viewed February 12, 2025).

[2] Id.

[3] Richard R. John, Spreading the News: The American Postal System from Franklin to Morse (Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Mass., London, England, 1995), at 37.

[4] Pub. L. 65–12, 40 Stat. 76.

[5] 40 Stat. 217, 219, discussed in Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919).

[6] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 63.

[7] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 63.

[8] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 64.

[9] Robert Justin Goldstein, Political Repression in Modern America (University of Illinois Press: Urbana and Chicago, 2001 edition), at 114.

[10] Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919), at 49-50.

[11] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 66. All issues of The Masses are available online at https://dlib.nyu.edu/themasses/ (viewed February 12, 2025).

[12] “Says Bopp Was To Back the Interdicted Film, Scenario Writer Also Swears Goldstein Told Him He Meant to Cater to German Turnvereiners,” Los Angeles Times, Wednesday, April 3, 1918, p. 13.

[13] Mutual Film Corporation v. Industrial Commission of Ohio, 236 U.S. 230 (1915). This decision would later be overturned by Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson, 343 U.S. 495 (1952).

[14] “Ten Years for Film Producer,” Los Angeles Times, Tuesday April 30, 1918, page 13.

[15] Reproduced at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/executive-order-2594-creating-committee-public-information (viewed February 14, 2025).

[16] Krystina Benson, “Archival Analysis of The Committee on Public Information: The Relationship between Propaganda, Journalism and Popular Culture,” The International Journal of Technology, Knowledge and Society, Vol. 6 No. 4, 2010, 151-163, at 153.

[17] George Creel, How We Advertised America: the first telling of the amazing Committee on public information that carried the gospel of Americanism to every corner of the globe (New York, and London: Harper & Brothers, 1920), at 50.

[18] George Creel, How We Advertised America, at 30-43.

[19] Krystina Benson, “Archival Analysis of The Committee on Public Information: The Relationship between Propaganda, Journalism and Popular Culture,” The International Journal of Technology, Knowledge and Society, Vol. 6 No. 4, 2010, 151-163, at 153.

[20] Nick Fischer, “The Committee on Public Information and the Birth of U.S. State Propaganda,” Australasian Journal of American Studies, July 2016, Vol. 35, No.1, The State and US Culture Industries (2016), 51-78, at 58.

[21] Michael Telzrow, “Committee on Public Information,” The New American, April 3, 2017, at 35.

[22] Michael Telzrow, “Committee on Public Information,” The New American, April 3, 2017, at 36.

[23] Cited in Cameron Givens, “The Color of Loyalty: Rumors and Race-Making in First World War America,” Journal of American Ethnic History, Winter 2023, Vol. 42, No. 2.

[24] Cited in Cameron Givens, “The Color of Loyalty: Rumors and Race-Making in First World War America,” Journal of American Ethnic History, Winter 2023, Vol. 42, No. 2, at 60.

[25] Cited in Cameron Givens, “The Color of Loyalty: Rumors and Race-Making in First World War America,” Journal of American Ethnic History, Winter 2023, Vol. 42, No. 2, at 62.

[26] Cameron Givens, citing CPI Bulletin No. 35, “Where Did You Get Your Facts,” August 26, 1918.

[27] Cited in Cameron Givens, “The Color of Loyalty: Rumors and Race-Making in First World War America,” Journal of American Ethnic History, Winter 2023, Vol. 42, No. 2, at 60.

[28] Andrew J. Lanham, “Radical Visions for the Law of Peace: How W.E.B. DuBois and the Black Antiwar Movement Reimagined Civil Rights and the Laws of War and Peace,” Washington Law Review, Vol. 99, No. 22 (2024), at 470, available at https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wlr/vol99/iss2/5/ (viewed February 15, 2024).

[29] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 117 (citing Van Deman to Major W.H. Loving, 3 May 1918, NARA Record Group 165, Kornweibel microfilm, reel 19, p. 617; Loving to Van Deman, 10 May 1918, quoted in Theodore Kornweibel Jr., “The Most Dangerous of All Negro Journals: Federal Efforts to Suppress the Chicago Defender during World War I,” American Journalism 11, no. 2 (Spring 1994), at 161.

[30] George Creel, How We Advertised America, at 192.

[31] Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917, Act Oct. 6, 1917, Ch. 106, 40 Stat. 11, § 19, available at https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/uscode/uscode1958-01005/uscode1958-010050a002/uscode1958-010050a002.pdf (viewed February 14, 2025).

[32] Executive Order 2729A, available at https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/executive-order-2729a-vesting-power-and-authority-designated-officers-and-making-rules-and (viewed February 14, 2025).

[33] Elisabeth Fondren, “’This is an American newspaper,’” Media History (2019), at

[34] David Hazemali, “Safeguarding Liberty? Repressive Measures Against Enemy Aliens and Ethnic Community Resilience in WWI United States: The Slovenian-American Experience, Annales, Ser. Hist.sociol. 33 (2023), at 491.

[35] David Hazemali, “Safeguarding Liberty? Repressive Measures Against Enemy Aliens and Ethnic Community Resilience in WWI United States: The Slovenian-American Experience, Annales, Ser. Hist.sociol. 33 (2023), at 493. Joseph Kovath’s treatment is also mentioned in Nicole M. Phelps, “’A Status Which Does Not Exist Anymore’: Austrian and Hungarian Enemy Aliens in the United States, 1917-21,” in Günter Bischof et al., eds., From Empire to Republic: Post World War I Austria (University of New Orleans Press). The original source appears to be J. C. Rider, “Alleged Cruelties and Violence to Austrians and Germans,” 19 November 1918, file no. 311.63/351, with the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

[36] Frederick C. Luebke, Bonds of Loyalty; German-Americans and World War I (Dekalb, Northern Illinois University Press, 1974), at 4-14; Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 157-58.

[37] Frederick C. Luebke, Bonds of Loyalty; German-Americans and World War I (Dekalb, Northern Illinois University Press, 1974), at 12.

[38] Pub. L. 65-150, 40 Stat. 553 (May 16, 1918), available at https://govtrackus.s3.amazonaws.com/legislink/pdf/stat/40/STATUTE-40-Pg553.pdf (viewed February 15, 2025).

[39] Act No. 292 is available online at https://lawphil.net/statutes/acts/act1901/act_292_1901.html (viewed February 15, 2025); and https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/ll/llserialsetpdf/04/23/4_/00/_0/0/04234_00_00/04234_00_00-001-0172-0000/SERIALSET-04234_00_00-001-0172-0000.pdf (viewed February 15, 2025); see also discussion in Alfred W. McCoy, Policing America’s Empire, The United States, the Philippines, and the Rise of the Surveillance State (University of Wisconsin Press: Madison, WI, 2009), at 99.

[40] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 144.

[41] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 132.

[42] Stephen Vaughn, “First Amendment Liberties and the Committee on Public Information,” The American Journal of Legal History, Apr. 1979, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 95-119, at 113.

[43] Pub. L. 65-150, 40 Stat. 553 (May 16, 1918), available at https://govtrackus.s3.amazonaws.com/legislink/pdf/stat/40/STATUTE-40-Pg553.pdf (viewed February 15, 2025).

[44] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 150, 162.

[45] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 150.

[46] Quoted in David F. Forte, “Righting a Wrong: Woodrow Wilson, Warren G. Harding, and the Espionage Act Prosecutions,” Case Western Reserve Law Review, Vol. 68 Isuse 4 (2018), 1097-1151, at 1100-1107.

[47] David F. Forte, “Righting a Wrong: Woodrow Wilson, Warren G. Harding, and the Espionage Act Prosecutions,” Case Western Reserve Law Review, Vol. 68 Isuse 4 (2018), 1097-1151, at 1107-10.

[48] Adam Tooze, The Deluge: The Great War, America and the Remaking of the Global order, 1916-1931 (Viking: New York, 2014), at 158-60.

[49] Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616, 618 (1919).

[50] Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616, 618 (1919); Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 289.

[51] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 150.

[52] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 209-10.

[53] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 221.

[54] Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919); Debs v. United States, 249 U.S. 211 (1919); Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616 (1919).

[55] “Senators Tell What Bolshevism in America Means,” New York Times, June 15, 1919, available at https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1919/06/15/97098596.pdf (viewed February 15, 2025).

[56] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 231-32.

[57] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 238-41.

[58] Quoted in Cameron Givens, “The Color of Loyalty: Rumors and Race-Making in First World War America,” Journal of American Ethnic History, Winter 2023, Vol. 42, No. 2, at 64 (citing Investigation Activities of the Department of Justice, Senate Doc. 153, 66th Congress, 1st session (Washington, DC: GPO, 1919), at 162).

[59] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 329-33.

[60] “Harding Under Fire for Hit at War Loan,” New York Times, June 9, 1917, at 3, quoted in David F. Forte, “Righting a Wrong: Woodrow Wilson, Warren G. Harding, and the Espionage Act Prosecutions,” Case Western Reserve Law Review, Vol. 68 Issue 4 (2018), 1097-1151, at 1135.

[61] Adam Hochschild, American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy’s Forgotten Crisis (Mariner Books: New York, Boston, 2022), at 337.

[62] Quoted in David F. Forte, “Righting a Wrong: Woodrow Wilson, Warren G. Harding, and the Espionage Act Prosecutions,” Case Western Reserve Law Review, Vol. 68 Issue 4 (2018), 1097-1151, at 1148.

[63] See generally Jeremy K. Kessler, “The Administrative Origins of Federal Civil Liberties Law,” Columbia Law Review, June 2014, Vol. 114, No. 5, pp. 1083-1166.

[64] Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. at 629-31.

[65] Liva Baker, The Justice from Beacon Hill: The Life and Times of Oliver Wendell Holmes (New York: HarperCollins, 1991), at 539.