In last week’s post,

I underscored the vital importance of centralizing, standardizing and coordinating HUMINT collection, a role that is performed today by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and described in general terms in U.S. Intelligence Community Directives (ICDs) 304, 310 and 311. By 1917, the British and French were already well apprised of the many negative consequences of failing to exhaustively coordinate, between themselves and within each of their respective governments. As Keith Jeffery notes in his comprehensive history of MI-6, “Inter-service rivalry…was unhealthy, and in some cases ‘disastrous,’ as it led to ‘denunciations, buying up of other services’ agents, duplication of reports, and collaboration between agents of the various Allied systems’, so that ‘information arrived at the various Headquarters in a manner which was not only confusing but sometimes unreliable and apt to be dangerous.’ Double reporting was a particular problem, in that there could be ‘an apparent confirmation of news really originating from the same source,’ owing to its having been received from ‘what appeared to be different and independent places of origin.’”[1]

This week covers mostly the defensive side of HUMINT, counterintelligence, with an emphasis on the U.S. front. Much of what follows serves as repeated illustrations of what happens when inter-organizational rivalry is allowed to run amok, as it was in Woodrow Wilson’s wartime cabinet.

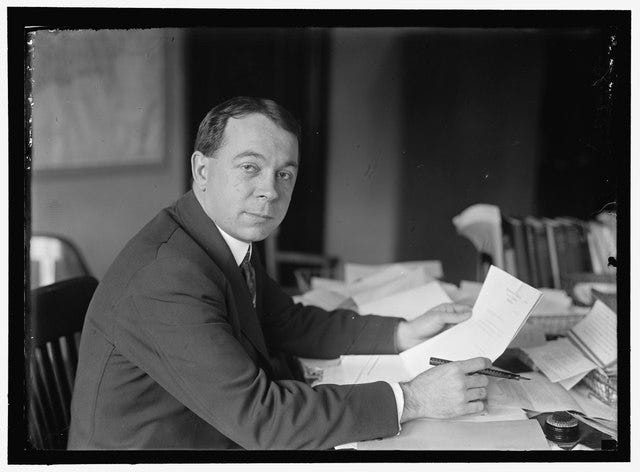

By the spring of 1917 the Bureau of Investigation (BI) under Chief Bruce Bielaski was already overwhelmed just trying to enforce the neutrality laws, much less the Espionage Act. In Chicago, Hinton Clabaugh, the superintendent of the BI’s field office, complained openly and bitterly to local businessmen about his lack of manpower and equipment. He had 15 detectives to cover all of Illinois, Wisconsin and Minnesota, and they had not a single automobile between them, forcing them to pursue suspects by streetcar. In February 1917, shortly after President Wilson cut off diplomatic relations with Germany, Clabaugh was visited by Albert M. Briggs, vice president of Outdoor Adventures, Inc., who had a proposal for him. Briggs, who had volunteered to serve in the Spanish-American War, desperately wanted to serve his country once again now that war against Germany seemed imminent. He had already offered, and Clabaugh accepted, free chauffeuring services for his detectives, since Briggs and a few of his friends happened to own cars. Now Briggs and a larger group of businessmen had a total of 75 cars they wanted to donate outright to the BI for use in multiple cities. They also wanted to create a national network of volunteers, people who could serve as an extra set of eyes and ears, eavesdropping on private conversations and passing tips to the BI about individuals possibly engaging in espionage.[2]

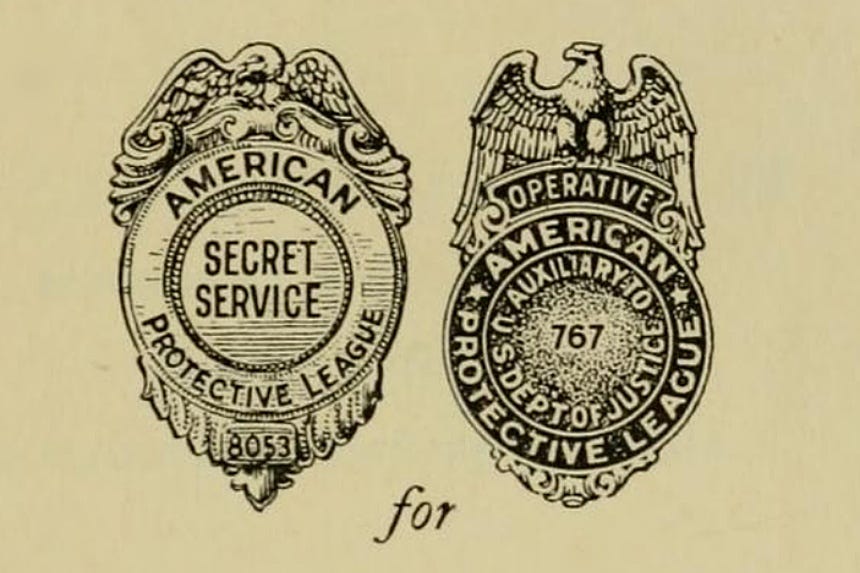

Briggs’ proposal, which Clabaugh relayed to Bielaski in Washington, culminated in a March 2017 meeting between Briggs and Bielaski in Washington, after which Briggs set about building what he decided to call the “American Protective League” (APL). He appears to have met with Van Deman on the same trip, who somehow came away with the impression that Briggs agreed to ensure that every single APL member “were to do absolutely nothing except for what they were requested to do by the Military Intelligence Branch in Washington.”[3] On March 20, 1917, the Justice Department officially “deputized” the APL to act as its agent.[4]

Briggs subsequently designated himself the APL’s General Superintendent and travelled quickly to multiple cities, setting up subordinate units from among his many business contacts. He encouraged them to create “Secret Service Divisions” that would work undercover in industries and public utilities and help keep any enemy aliens under surveillance. Each unit chief was to recruit a number of volunteers willing to undertake a “sworn duty” to report to the chief any instance of disloyalty, industrial disturbance, or any other matter “likely to injure or embarrass” the U.S. Government.[5]

Other similar organizations were already in existence, although with slightly different goals. The National Security League (NSL) had been co-founded in December 1914 by retired General Leonard Wood, former Governor-General of the Philippines, with a non-partisan political agenda that called for an expanded military, government regulation of industry, and other aspects of military preparedness. Its day-to-day leaders, who had a decidedly pro-British, anti-German bent from the earliest days of World War I, enjoyed financial and other support from such luminaries as Theodore Roosevelt, Elihu Root, Thomas Edison, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and J.P. Morgan.[6] In 1915, Republicans within the NSL who felt the organization had become too partial towards the Wilson Administration broke off to form a splinter group called the American Defense Society (ADS). The ADS, which promoted “100% Americanism,” promptly began calling for the banning of German language instruction in public schools, loyalty oaths for teachers, and closure of all German-owned insurance companies in the United States. By August 1917, the ADS had formed an “American Vigilance Patrol” that aimed to eradicate “seditious street oratory” by having city police arrest speakers for disorderly conduct.[7]

According to Van Deman, there were “dozens” of these volunteer organizations that suddenly “sprang up” across the United States, almost from the moment war was declared, devoted to chasing down all the German spies. The British anti-German propaganda effort, aided by sensationalistic journalism, had been so successful that

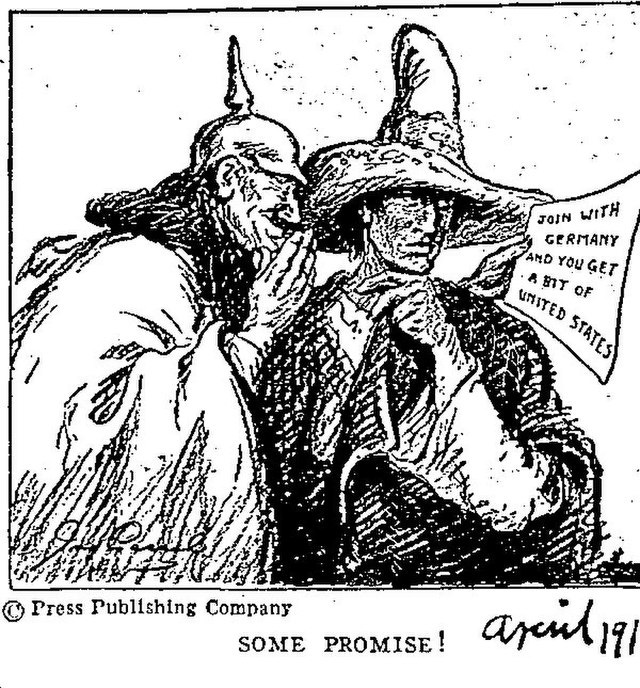

“many Americans believed that a declaration of war would transform America into a battlefield, with every one of the million resident German aliens an agent of the Kaiser. Mexicans in league with Germany would march north, retake Arizona and New Mexico, and cut off California from the rest of the country. Japanese would then land on the Pacific Coast and invade California. In the East, German submarines would shell New York. Sabotage would be particularly widespread in the heavily industrialized Northeast. Spies, of course, were believed to be operating everywhere.”[8]

In California the level of public hysteria was particularly severe.

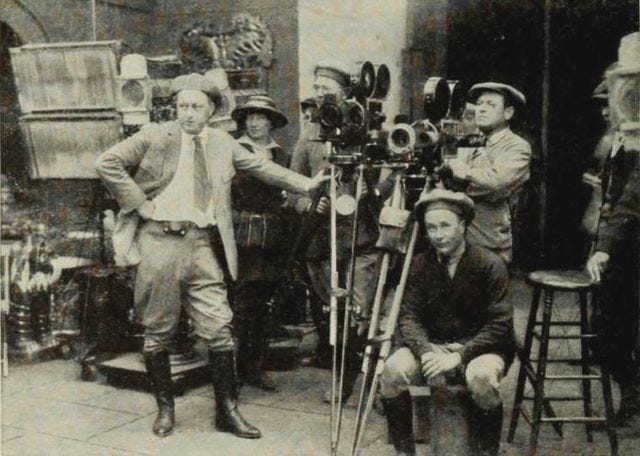

“Movie producer Cecil B. DeMille offered the city of Los Angeles a troop of seventy-five studio men armed with a machine gun, rifles, and ammunition, while in San Diego a private rifle club mobilized itself as the Cabrillo Rifles and prepared to protect the city from invasion. There was absolutely no evidence that either Japan or Mexico knew about the Zimmermann proposal—except through American newspapers—or that either government would accept the German invitation to war against the United States. Nevertheless, Pacific Coast racists had talked for so long about the ‘yellow peril’ and the threat of a Japanese invasion that conservatives and progressives alike prepared for actual hand-to-hand combat.”[9]

From Van Deman’s perspective, the proliferation of volunteer counterintelligence agents was “an extremely dangerous development and it was evident that these organizations must be stopped in their activities at once.”[10] Accordingly, both Van Deman and Bielaski felt the nation was better off with the APL as the single “official” deputized partner of the U.S. Government than with dozens of freelancers. It was quite a popular concept within U.S. industry as well; “at a time when labor was just beginning to reach for a larger share in shaping—and enjoying—the American economy, conservative businessmen were delighted to have such a secret network to inform them of the activities of workers.”[11] Industrialists in Pennsylvania gladly contributed 50 dollars a month to the APL.

To California labor reformers who should otherwise have been wary of APL spies within industries, it seemed a “reasonable alternative to barbed wire and machine guns.” [12] To Attorney General Watson, this was a much more viable alternative to the Justice Department having to pay, train and discipline thousands of new federal officers.[13]

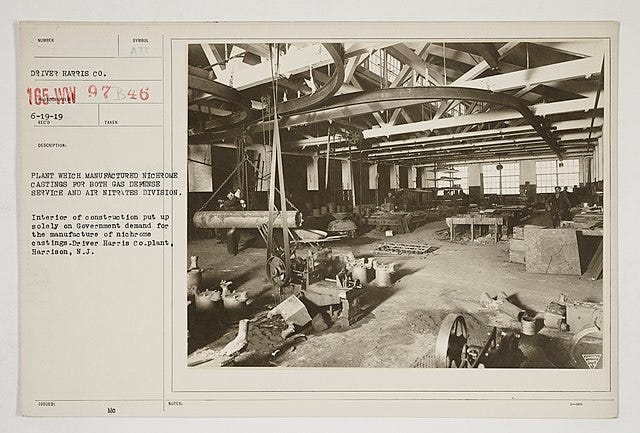

The War Department, at more senior levels, quickly understood the game that was being played by industry. The APL almost immediately set its sights on the labor organization International Workers of the World (IWW), known as the “Wobblies,” which like the APL was also headquartered in Chicago, and which made no attempt to hide its opposition to the war as a scheme by Wall Street plutocrats to make the world safe for “predatory capitalism.” APL members considered such speech, along with calling for strikes, to be treasonous and began trailing IWW members, posing as journalists at their meetings, and wiretapping their conversations.[14] General Thomas Henry Barry, another Philippines veteran who now commanded federal troops in the Midwest, complained to Secretary of War Newton Baker that factory owners would use their APL spies to repeatedly predict that a strike was about to be called, then demand the protection of federal troops. Indeed, as early as May 6, 1917, the U.S. Attorney in St. Louis had leaned on Barry to send troops to avert a strike; he refused to do so, noting that the governor of Missouri had not requested them.[15]

But to Van Deman in Washington, who had used a network of native informants in the Philippines in order to ultimately serve the interests of U.S. and Filipino business elites, the arrangement between the U.S. government and the APL made perfect sense.[16] Bielaski approved the APL’s special “badge,” which was made available to all officers of the League for 75 cents.

Soon, neither Bielaski nor Briggs had any idea how many APL members there were, nor were APL members clear on whether they reported to the BI, Military Intelligence, the Treasury Department’s Secret Service, or simply the federal agency contacts of their choice.[17] The British, who were primarily concerned about protection of war material from German sabotage, were frustrated at the decentralized nature of American governance and the complete lack of coordination and initiative within the federal Executive Branch.[18] President Wilson refused to settle the ongoing feud between Attorney General Watson and Treasury Secretary McAdoo, which was only exacerbated when APL members insisted on referring to themselves as “Secret Service agents.”[19]

It was the APL members’ insistence on making arrests of their fellow citizens that caused the Justice Department to reign them in a few months later or at least attempt to. The U.S. Congress’ formal declaration of war was quickly followed by its passage of the Selective Service Act of May 18, 1917, requiring all men ages 21 to 30 to register for the military draft.[20]

To the APL, this offered all the opening it needed to pursue any statements of IWW opposition to the draft as a potential violation of federal law, although it proved extraordinarily difficult to obtain evidence of actual criminal activity. Some vigilantes resorted to simply attacking IWW members in the street. On September 5, 1917, the BI and the APL spearheaded a series of raids on IWW offices across 20 U.S. cities. Three weeks later, 166 IWW members were indicted on charges of “conspiracy to prevent by force the execution of the laws of the United States.”[21]

The Selective Service Act was the brainchild of Army Provost Marshal General Enoch Crowder, a Judge Advocate General attorney who had served under William Howard Taft in the Philippines and in fact had drafted the Philippine criminal code. In order to apprehend “deserters” who failed to report for duty, Crowder in the fall of 1917 offered the public a $50 reward to anyone who delivered such individuals to the nearest Army camp, which would then be recouped from the new soldier’s first paycheck.[22] This became yet another boondoggle for the APL. APL members quickly adopted the illegal practice of stopping men in the street, demanding to see their registration card, and then detaining them until their status could be confirmed against the local draft boards.

Eventually the general ruthlessness with which the first military mobilization was conducted, including against legitimate conscientious objectors, led to some media criticism and a subsequent softening of the Wilson Administration’s approach. Attorney General Gregory began centralizing enforcement of all wartime legislation under a War Emergency Division and tightening the reigns on Bielaski and his army of APL volunteers.[23] The Justice Department told the APL to retrieve as many “Secret Service badges” as possible and ensure that their members no longer used them or otherwise implied that they were acting under federal authority; whether the APL actually complied with this directive is doubtful.[24]

At this point, the Justice Department rivalry with Treasury faded into the background (Treasury essentially lost), to be replaced by a raging debate, including in Congress, over whether the German spies should be dealt with by civilian authorities at all, as opposed to either the Army or the Navy. Despite the “Hindu conspiracy trial” opening on November 20, 1917 in San Francisco to breathless media coverage (the context for which I discussed in this post),

Senator Henry Cabot Lodge was one of many who wondered aloud on the Senate floor whether the Justice Department was at all effective, as the country was supposedly teeming with German spies, and yet there hadn’t been any successfully prosecuted. In England and in most of Europe, espionage was a matter for the military authorities to handle under martial law. Militarists in the United States, watching such developments overseas, “waited impatiently for the government to find a spy and execute him.”[25] Attorney General Watson now found himself fending off legislative proposals to create “war zones” around defense plants, with the military given exclusive jurisdiction in those areas.[26]

The APL, having successfully decimated its IWW nemesis and now casting about for new projects amid shifting political winds, began to form an even closer relationship with Van Deman’s Military Intelligence Division (MID) in Washington. Van Deman welcomed the help but seemed to prefer recruiting his own personnel, who reported directly to him rather than through the APL, avoiding possible scrutiny and any resulting turf battles with the Justice Department. He quietly grew his own empire using connections he had maintained through the State Department and Treasury/Secret Service, contacts who now had been cut out of the spy-catching action by the Justice Department.

One of his recruitment efforts was directly aimed at what he called the “Negro subversion problem.” In the fall of 1917, a contact in the U.S. State Department sent Van Deman a Secret Service report indicating that property in Harlem worth over $500,000 had recently been purchased by Black buyers who were being used merely as a front for German interests, through the Wall Street firm Kuhn, Loeb and Company. There were also rumors of a German agent based in a furniture store in Harlem, hatching some sort of “plot” in Mexico involving Black unrest. Just prior to an impending trip of his to Mexico, the German had told a number of local Black acquaintances that “they owed nothing to the United States Government,” and “contrasted the treatment of the negroes by the whites of this country with the kindness he claimed they would receive if the Germans were in control.”[27]

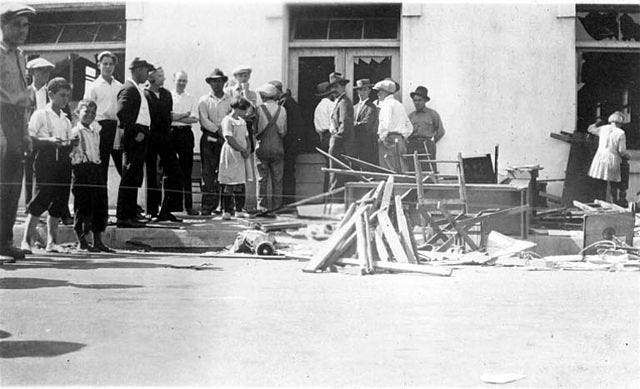

Black Americans indeed did not owe much to the administration of Woodrow Wilson, who upon entering office in 1912 had invited his Cabinet members to re-segregate the federal civil service and hosted a White House screening of the Ku Klux Klan apologist film Birth of a Nation. In 1917, racial unrest was at one of its highest points in U.S. history. As war production sped up with the entry of the United States into the conflict, southern Black laborers had made their way north to factories, which then provoked race riots from white factory laborers similar to those responding to Sikh laborers in the Northwest lumber yards in 1907. In East St. Louis, Illinois, an enormous race riot broke out on July 2, 1917 after the APL spies had tried but failed to avert a strike against Black laborers; by the end of it, nine whites and thirty-nine Blacks had been killed, with Illinois militiamen who had been brought in to quell the riots having mostly joined the white laborers in beating and shooting Black men and looting their houses. Theodore Roosevelt publicly condemned the “infamies imposed on colored people,” but President Wilson took no action.[28]

Only weeks after Van Deman received the Secret Service report, there was a mutiny within the 24th Infantry Regiment in Houston, one of the “Buffalo Soldier” regiments consisting of all Black enlisted personnel, that had been precipitated by weeks of harassment and racial slurs hurled at the regiment’s soldiers by local whites.[29]

Van Deman eventually recruited “two extremely capable and reliable Negro men after most careful investigation,” in order to counter the Central Powers’ efforts to “agitate” the Black American population.[30] The purpose of Van Deman’s two agents, as he saw it, was to counteract German propaganda by visiting every community in the United States in which “unrest” was reported, and “remain long enough in each community to determine what the real trouble was and then by conversations and formal talks in Negro churches and other meeting places to persuade the Negroes in the community that the actions being suggested to them by persons who had previously circulated among them would lead to very serious consequences if not abandoned.”[31]

Some academic contacts led Van Deman’s division to Hallie E. Queen, who taught in the District of Columbia and who had recently visited East St. Louis with the Howard University Red Cross Auxiliary to assist with relief efforts. Van Deman was also placed into contact with Joel Spingarn, Chairman of the Board of Directors of the NAACP, who had just joined the Army, and who warned Van Deman that Queen’s reporting could be somewhat unreliable.[32]

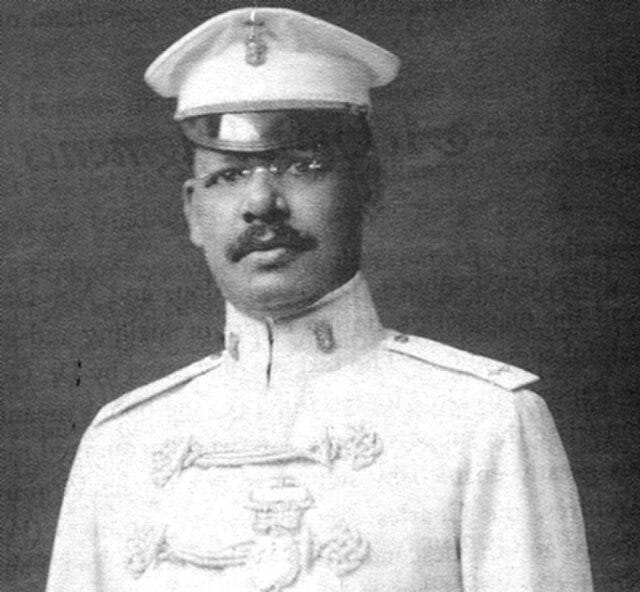

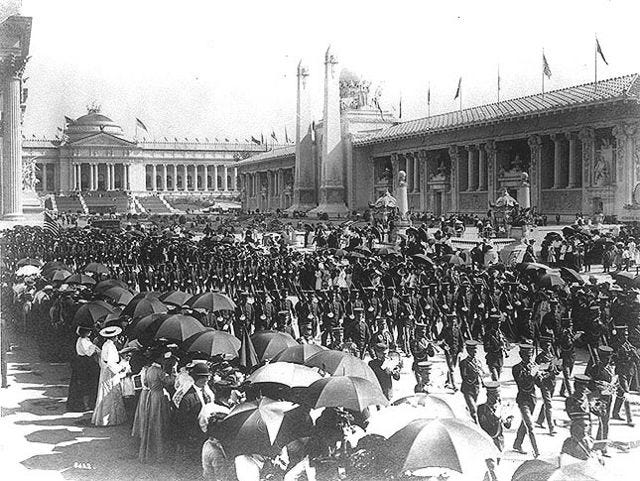

The other “extremely capable and reliable Negro man” recruited was most likely someone Van Deman had crossed paths with long before in the Philippines. Major Walter Howard Loving, who was raised in the District of Columbia, joined the 24th Infantry in 1893 and quickly became known as an outstanding military musician (cornetist). He was discharged as a U.S. Army lieutenant in Manila in 1901, only to be recommended by William Howard Taft in 1902 to organize the Philippine Constabulary Band. Under his leadership, the Constabulary Band performed at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis and as the lead unit in Taft’s presidential inaugural parade in 1909. To Loving, Spingarn and Queen, their affiliation with U.S. Military Intelligence was a valuable opportunity for them to convey to the higher echelons of the U.S. Government the root causes of and possible remedies for Black unrest, which had less to do with German propaganda than with discriminatory and violent treatment by white Americans. While Loving was respected as the MID’s expert on “Negro Subversion” and directed the work of white officers, he was required, under Wilson administration rules for all federal personnel, to segregate himself in a separate building, with his own telephone and safe.[33]

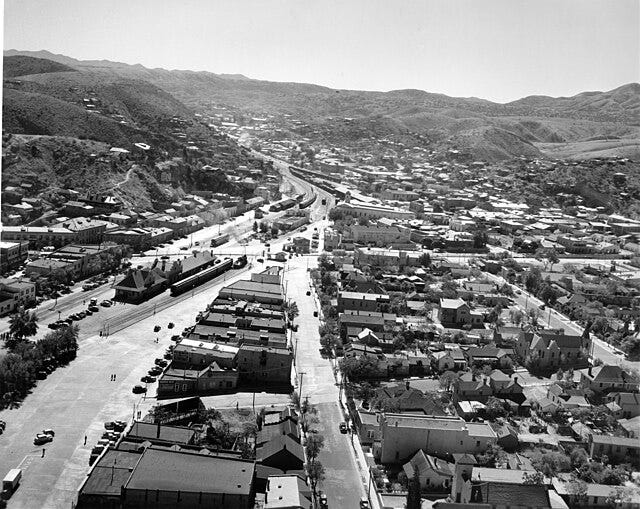

By early 1918 Van Deman was building networks of informants in the Midwest as well—retired military officers, lawyers, industry detectives.[34] In the Western Department, a colonel in Military Intelligence similarly formed his own Volunteer Intelligence Corps, purportedly consisting of a thousand “patriots” supplying him with information on opponents of the war, also completely outside the APL.[35] But it was a single volunteer who had shown up one day unsolicited, at an MID office in Nogales, Arizona, who set into motion a sequence of events that led to the single greatest U.S. counterintelligence accomplishment of the war—the successful arrest, conviction and sentencing to death of the only German spy to have been criminally charged by the United States with espionage during World War I.

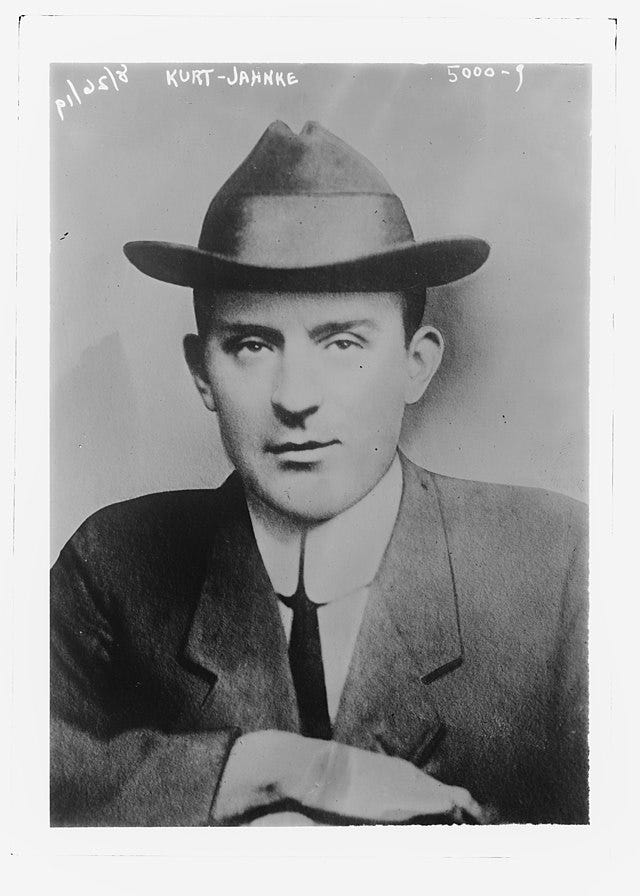

The volunteer who showed up in Nogales that day was Dr. Paul Bernardo Altendorf, a Jewish refugee from Krakow who had fled the Austro-Hungarian military draft in the 1890s and eventually settled in Yucatán, Mexico to practice medicine. The year 1915 brought a huge influx of Germans and Austro-Hungarian into the region, and following a chance encounter on a train in the summer of 1917, Altendorf was recruited into German intelligence by Kurt Jahnke, one of the few German-Americans who actually was a paid German spy. A U.S. Marine veteran who had served briefly in the Philippines, between 1914 and 1917 Jahnke had organized various covert sabotage operations under the direction of German Consul General Franz Bopp while based in San Francisco, where he had long worked as a private detective. Then, like most of the German covert apparatus, he had been forced to relocate to Mexico when the U.S. broke off diplomatic relations with Germany, as without the embassies and consulates the spies had no secure means of communicating with Berlin; this is why all the spy-hunters across the United States were having such difficulty apprehending them. Jahnke arranged for Altendorf to be commissioned as a captain in the German Army and a colonel in the Mexican Army, with the full approval of Mexican President Carranza.[36] Jahnke came to trust Altendorf so much that on one occasion he left him in charge of his entire office for a period of 13 days. [37]

What Jahnke didn’t know was that Altendorf was also a naturalized U.S. citizen. He also didn’t know that the massive influx of Germans and Austrians into Yucatán had inflamed Altendorf’s latent feelings of Polish nationalism. Upon recruitment into German intelligence, Altendorf had promptly made his way to the MID office in Nogales and offered his services as a double agent. He was given the cover designations of “Johnson” and “MID Agent A-1” and was handled by MID officer Byron Butcher.[38] He turned out to be such an outstanding double agent that the one BI agent sent to surveil German spies in Mexico City, William Neunhoffer, ended up surveilling Dr. Altendorf (one of many examples that underscores the importance of coordinating HUMINT operations across all intelligence agencies).

The Germans had an even more valuable agent than Altendorf, a Black Canadian, as indeed there was a German plot developing in Mexico to stir up Black unrest in the United States, on a scale similar to that of the “Hindu conspiracy.” William “Guillermo” Gleaves, born in Montreal in 1870, had spent much of his life in Pennsylvania, had lived in Mexico since 1893 but had also, like Loving, served for a time as an officer in the Philippines Constabulary. Starting in 1917, Gleaves worked directly for Consul General Dr. Friedrich Rieloff, who instructed him to enroll as a member of the IWW and then sent him to El Paso with $1500 to see if he could bribe some soldiers to mutiny. Gleaves returned to Mexico with news that the possibilities for mutiny seemed promising.

On January 15, 1918, Jahnke offered him an even more bold proposal: would Gleaves, on behalf of a “Revolutionary Association” that had formed in Mexico with German backing, help lead a revolution in the United States? Gleaves responded enthusiastically that, on his recent trip to El Paso, he had learned of a secret organization linking the different Black U.S. Army regiments with plans for a widespread mutiny, similar to that of the 24th Infantry but on a much larger, potentially national scale. Jahnke told Gleaves that if he could foment an initial mutiny within the 10th Cavalry at Fort Huachuca, this would provide an opening for a full-scale invasion of the United States from Mexico by a coalition of Germans, Mexicans and South Americans.[39]

Jahnke decided that the best people to accompany Gleaves on this mission were his most trusted agent Dr. Altendorf, and one of his most experienced saboteurs, Lothar Witzke, who was to assassinate MID agent Byron Butcher in Nogales as part of the same mission. Jahnke and Witzke, who had met in San Francisco, had carried out a number of sabotage operations against Allied shipments between 1914 and 1917. During that time period, Witzke developed the alias of a Russian émigré named Pablo Waberski, which is how Jahnke now introduced him to Gleaves. Altendorf, upon receipt of his own instructions to accompany Witzke, quickly and discretely made his way to the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City, proclaiming to the astonished military attaché, Major R.M. Campbell, “I am Mr. Butcher’s man!” and producing the MID officer’s card. He explained the entire German plot and provided documentation and detailed instructions for Campbell on how to convey the information securely to Byron Butcher in Nogales.[40]

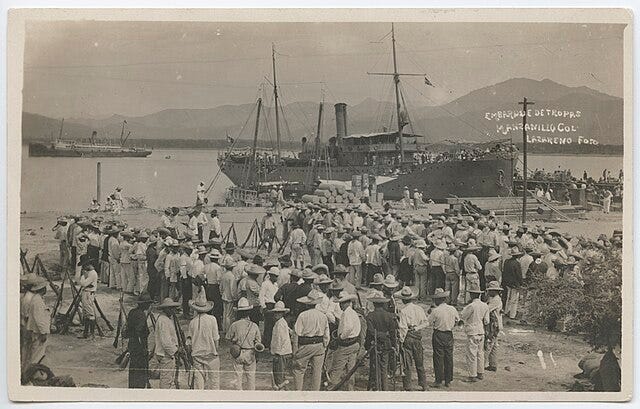

The next day, Altendorf, Witzke and Gleaves boarded a train from Mexico City to Manzanillo, Altendorf and Witzke in one car, Gleaves in another.[41] In Guadalajara Altendorf got Witzke drunk and rifled through his belongings, finding and copying the enciphered document that Jahnke had given to Witzke in order to authenticate himself to German intelligence during his journey.[42] Gleaves continued to travel separately as they made their way to Manzanillo, with Altendorf only gradually becoming aware that there was a third man in their party. He finally introduced himself to Gleaves and managed to learn his name; Gleaves, being unsure of Altendorf’s status, told him he was a colonel in the Mexican Army.[43]

Gleaves then made his way to Nogales, Senora (just over the border from Nogales, Arizona) while the other two stayed in Hermasillo. Witzke and Gleaves began to coordinate with purported U.S. army deserters, whom Gleaves said were willing recruits for the planned mutiny. Witzke told Gleaves he would be crossing the border into Nogales, Arizona, the next day.[44]

Butcher had already received the message that Altendorf had conveyed to him via Major Chapman in Mexico City, that he would be arriving at his location with two German spies in tow in a matter of days, one of them under the alias Pablo Waberski.[45] Butcher was immediately notified by border officers when Witzke showed up at the border as “Pablo,” and he decided to simply monitor his movements rather than arrest him, not knowing whether Witzke had evidence on his person of his status as a spy.[46]

Altendorf was soon on hand to remove any doubts. The day Witzke left for Nogales, Altendorf had trailed behind him in disguise, gone to the U.S. consulate in Nogales on the Mexican side, and confirmed to U.S. authorities that Witzke had incriminating documents on his person. The next day, February 2, 2018, Butcher had Witzke arrested.[47] His incriminating documents, which were enciphered, were quickly transmitted to Herbert Yardley’s MI-8 section in Washington for deciphering.[48].

(I wrote about Yardley and MI-8 in this post):

Within a few days, U.S. military intelligence operatives in Nogales, Mexico had also apprehended the mysterious Black man, Gleaves, whom they now knew to be Witzke’s accomplice and who had been seen wandering about town, unsure how to proceed without word from Witzke. It was only at this point that they learned—further underscoring the importance of careful coordination of HUMINT operations between agencies—that Gleaves was in fact a British covert agent who had been working for British naval intelligence in Mexico since 1914. The British naval attaché in Mexico City, former Parliamentarian Alfred Edward Woodley Mason, reported directly to Admiral Blinker Hall in London.[49] Gleaves had been instrumental in helping the British identify some of the methods of radio communications being used by the Germans in Mexico, which naval intelligence could then intercept and then have decrypted by "Room 40" back in London. (I have previously discussed Admiral Hall and Room 40’s contributions near the end of this post):

Then, in 1917, Mason had sent Gleaves to infiltrate the German-Mexican spy network itself, which he obviously had done quite successfully.[50] British intelligence had been monitoring Witzke’s covert mission the entire time.

The combined testimony of Altendorf and Gleaves at Witzke’s court-martial, which began August 16 and was closed to the public, was damning, particularly as validated by testimony by Campbell, Butcher, and the array of U.S. consular officials who had interacted with Altendorf. The final witness for the prosecution was Captain John Manly from MI-8, who along with his collaborator Edith Rickert had quickly deciphered the secret document found on Witzke’s person, which read: “To the Imperial Consular Authorities in the Republic of Mexico. Strictly Secret! The bearer of this is a subject of the Empire who travels as a Russian under the name of Pablo Waberski. He is a German secret agent.”[51] The commission conducting the court-martial found Witzke guilty of espionage and sentenced him to death by hanging.[52]

Unfortunately for Van Deman, all of this activity on the part of MI officers and their vast networks of agents could only stay below the Justice Department’s radar screen but for so long. Attorney General Gregory complained to War Secretary Baker that the MID had decided to simply supplant the Justice Department’s investigative services. By June 1918, Baker had had enough of Van Deman’s incessant empire building and sent him to Europe to serve in some sort of subordinate and/or consultative position under Major Dennis E. Nolan, the head of intelligence for the American Expeditionary Force (AEF). He was replaced as head of the domestic MID by Lieutenant Colonel Marlborough Churchill, who was seen as more cautious about opening military investigations. [53]

Witzke’s death sentence was also never carried out. Saved by the bell, with the end of hostilities in Europe that November, his death sentence was eventually commuted to confinement at hard labor by President Wilson in 1920. He was then pardoned and released by President Calvin Coolidge in 1923 and deported to Berlin. He went on to serve in the German Army in World War II. It was not until long after his release that U.S. authorities learned of his central role in the infamous and deadly “Black Tom Island” explosion of 1916.

Still, the U.S. Army learned and institutionalized a great deal about HUMINT operations during the First World War. In particular, those who served with the AEF on the Western Front were more fully able to learn and practice HUMINT, such as POW interrogations, alongside their French and British allies, with none of the interagency struggles associated with the domestic front. The U.S. Army made extensive modernizing modifications to its field manuals, regulations and training curriculum governing intelligence following the First World War.[54]

However, both during and after the war, it became evident how much more fraught and complicated these activities could be when carried out domestically. Treasury Secretary McAdoo’s suggestion that there be some sort of “centralized intelligence agency” would not be taken up for another 30 years. In the meantime, the uneven U.S. experience with HUMINT on the home front during World War I was one of many important factors leading to the eventual bifurcation in U.S. law and practice between foreign and domestic intelligence.

[1] Keith Jeffery, MI6, the History of the Secret Intelligence Service, (Bloomsbury Publishing: London, 2010), at 74.

[2] Joan M. Jensen, The Price of Vigilance (Rand McNally: Chicago, 1969), at 18-21.

[3] Ralph E. Weber, ed., The Final Memoranda: Major General Ralph H. Van Deman, USA ret.,1865-1952: Father of U.S. Military Intelligence (Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1988), at 30 (firsthand account of Van Deman) (emphasis added).

[4] Dr. Harold C. Relyea, Congressional Research Service, “The Evolution and Organization of the Federal Intelligence Function: A Brief Overview (1776-1975), contained in Book VI of the Final Report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities,” United States Senate (U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, 1976), at 103.

[5] Joan M. Jensen, The Price of Vigilance (Rand McNally: Chicago, 1969), at 21-25.

[6] Mark R. Shulman, "The Progressive Era Origins of the National Security Act," Dickinson Law Review, Winter 2000, 289-330, at 300-05, available at https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1222&context=lawfaculty (viewed January 20, 2025).

[7] Jensen at 96.

[8] Jensen at 27.

[9] Jensen at 28.

[10] Ralph E. Weber, ed., The Final Memoranda: Major General Ralph H. Van Deman, USA ret.,1865-1952: Father of U.S. Military Intelligence (Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1988), at 30 (firsthand account of Van Deman).

[11] Jensen at 28.

[12] Jensen at 32.

[13] Jensen at 34.

[14] Jensen at 57.

[15] Jensen at 33.

[16] Dr. Harold C. Relyea, Congressional Research Service, “The Evolution and Organization of the Federal Intelligence Function: A Brief Overview (1776-1975), contained in Book VI of the Final Report of the Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities,” United States Senate (U.S. Government Printing Office: Washington, 1976), at 103.

[17] Joan M. Jensen, The Price of Vigilance (Rand McNally: Chicago, 1969), at 47-49.

[18] Jennifer Luff, “The Anxiety of Influence: Foreign Intervention, U.S. Politics, and World War I,” Diplomatic History 44(5): 756-785 (November 2020), at 772. In Britain, by contrast, the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA), along with the Aliens Restriction Act, had given Her Majesty’s Government (HMG) powers “close to martial law.” Enemy aliens were required to register with the police and forbidden to live in a large number of “prohibited areas” without police permits. Christopher Andrew, Defend the Realm: The Authorized History of MI5 (Alfred A. Knopf: New York, 2009), at 52-53.

[19] Jensen at 47-56.

[20] Pub. L. 65–12, 40 Stat. 76.

[21] Jensen at 74-76.

[22] Jensen at 82-83.

[23] Jensen at 84-85.

[24] Jensen at 89, 94.

[25] Jensen at 105.

[26] Jensen at 106.

[27] Mark Ellis, Race, War and Surveillance: African-Americans and the United States Government During World War I (Indiana University Press: Bloomington and Indianapolis, 2001), at48.

[28] Jensen at 62-63.

[29] Mark Ellis, Race, War and Surveillance: African-Americans and the United States Government During World War I (Indiana University Press: Bloomington and Indianapolis, 2001), at 48-49.

[30] Ralph E. Weber, ed., The Final Memoranda: Major General Ralph H. Van Deman, USA ret.,1865-1952: Father of U.S. Military Intelligence (Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1988), at 33-34 (firsthand account of Van Deman)

[31] Ralph E. Weber, ed., The Final Memoranda: Major General Ralph H. Van Deman, USA ret.,1865-1952: Father of U.S. Military Intelligence (Scholarly Resources, Inc., 1988), at 33-34 (firsthand account of Van Deman)

[32] Mark Ellis, Race, War and Surveillance: African-Americans and the United States Government During World War I (Indiana University Press: Bloomington and Indianapolis, 2001), at 49.

[33] Ellis at 57-59.

[34] Joan M. Jensen, The Price of Vigilance (Rand McNally: Chicago, 1969), at 123.

[35] Jensen at 122.

[36] Investigation of Mexican affairs: Hearing before a subcommittee of the Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, Sixty-sixth Congress, Volume 1, 1919, p. 459. Available at https://www.loc.gov/resource/gdclccn.21020652v1/?sp=464&st=image (viewed January 25, 2025).

[37] Id.; see also Jamie Bisher, the Intelligence War in Latin America, 1914-1922 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2016), at 135, 184.

[38] Bisher at 184.

[39] Bill Mills, Agent of the Iron Cross: The Race to Capture German Saboteur-Assassin Lothar Witzke During World War I (Roman & Littlefield Publishers, 2023), at 69-71.

[40] Mills at 73.

[41] Mills at 81-82.

[42] Mills at 84.

[43] Mills at 88.

[44] Mills at 107-10.

[45] Mills at 110.

[46] Mills at 110.

[47] Mills at 115-17.

[48] Mills at 118.

[49] Mills at 118-19.

[50] Affidavit of William H. Gleaves, A Former Member of the British Intelligence Department in Mexico, Verified January 31, 1927, State of New York, County of New York (on file with author and with Agent of the Iron Cross author Bill Mills).

[51] Mills at 148. The story of the deciphering of Witkze’s letter by Manly and Rickart is recounted in David Kahn, The Code Breakers (The MacMillan Company, 1972), at 354. Manly and Rickart would go on to collaborate on an eight-volume work entitled The Text of the Canterbury Tales, “in which, by a tedious collation of scribal errors and variant readings in more than 80 manuscripts of the medieval masterpiece, they reconstructed a text that is as close to the poet’s own original as the extant evidence allows. The cast of mind that can thus sort out, retain, and then organize innumerable details into a cohesive whole was just what was needed for the Gothic complexity of the 424-letter Witzke crytogram.” Id.

[52] Mills at 156.

[53] Joan M. Jensen, The Price of Vigilance (Rand McNally: Chicago, 1969), at 124.

[54] Mark Stout, World War I and the Foundations of American Intelligence (University Press of Kansas, 2023), at 271-73.